CHAPTER XXVII

THE STORY OF THE QUEEN

AMONG most nations it is customary for the kingship to be handed down from father to son, but no such rule exists in the bee-city. Although we call one of the bees the Queen, she is not really a queen in the ordinary sense of the word. She does not rule the hive, nor can she command the bees to do this thing or that, and a far better name for her would be the Mother bee.

Up to the seventeenth century it was thought that a hive was ruled over by a king-bee, and it was not known that this large bee was the mother of all the other bees, and yet this is so, as we have already seen. Whether or not a queen shall be born depends on the wish of the workers, and it is surprising to find that a queen is developed from an ordinary egg, which, if it were not subjected to certain different processes, would turn into a worker bee.

PLATE XXII

From a photograph by] [E. Hawks

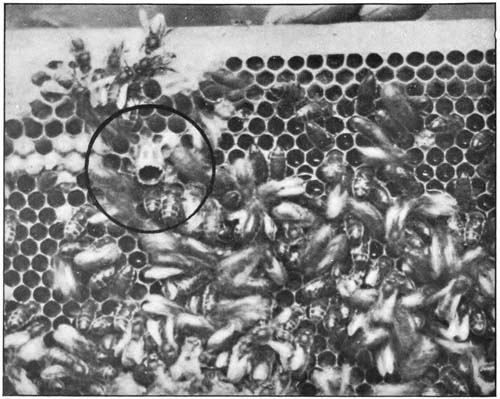

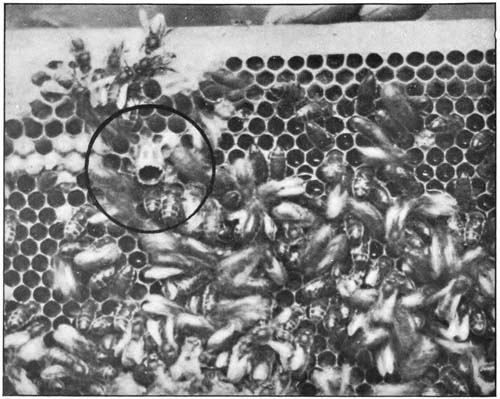

An Empty Queen Cell

When the bees desire that a queen shall be born, the builders and sculptors are first consulted. They set to work to make three or four queen cells, or, as we might call them, royal cradles; in one of them the future queen will be reared. We have already seen that queen cells are different from the ordinary cells, and that for their accommodation a part of the comb is cut away. This gives better ventilation, and the royal cells hang downwards from the comb as seen in Plate XXI. The nurse bees now place in the first an egg from one of the worker cells, but this egg must not be more than three days old, otherwise a queen would not be produced, no matter what efforts the bees might make. Eggs are placed in the other cells at intervals of three days. On the fourth day the first egg hatches into a grub, just as it did in the case of the worker bee, whose career it resembles up to this stage. But now the nurse bees, instead of feeding it upon chyle food, commence to supply it with “royal jelly” as it is called. This is a very rich form of food, and is only given to those grubs which it is intended shall become queens. The nurse bees continue to pay special attention to the little grub, and give it as much of the royal jelly as it can take. This goes on until the ninth day, when the grub spins a cocoon and the cell is closed up. On the sixteenth day from the time the egg was laid the young princess will be ready to leave her cell; she will then commence to gnaw the floor in order that she may get out. In Plate XXII. there is shown an empty queen cell, the floor of which has been cut away in this manner.

Thus we see that the making of the queen rests entirely with the workers themselves, and depends simply on an egg being placed in a certain kind of cell, and having special food and plenty of ventilation. After the queen has been hatched, the royal cell is cut away, and its place filled with honey cells. The wax of the cell is not wasted, but used in the construction of new comb.