IV

CHARACTER OF THE BROADLEAF FORESTS

IF the individual trees of the two main groups that were described in the opening chapter impress us differently as they belong to the one or the other, it will be found that the two kinds of forests likewise convey distinct impressions. Different in aspect, they are also distinguished one from the other by the different atmosphere or spirit that pervades them. Taking leave here of the trees as individuals, I shall now examine the characteristics of woodland scenery.

It has been said that the broadleaf trees grow naturally over a wide extent of territory. Of the unbroken wildernesses that covered the eastern parts of our country when it began to be colonized, only fragments remain. A few States are still densely wooded, but in these the forces which have caused the disappearance of similar forests in other regions have now begun to assert themselves. Some will yield to their old enemy, the ravaging fire that could so often be prevented; others must ultimately recede to make way for agriculture; many will be removed more rapidly for the sake of their material. It is confidently to be expected, however, in view of the widening influence forestry is exerting, that where it is desirable a provision will be made for a future growth to replace the present one.

Of the broadleaf forests there are many types. There are forests of oak and chestnut, of maple and beech; dry upland forests, and the tangled woods of the swamps. There are young thickets of birch and aspen, of willow and alder, and scrubby oak barrens. There are second-growth forests, and now and then even a patch of fine old virgin timber. In size, also, there is a great difference, from the grove that covers the hilltop to the unbroken forest that stretches over an entire mountain range.

It appears, therefore, that variety is one of the marked characteristics of our eastern woods. As several hundred different kinds of trees enter into their composition under every form and modification of circumstance, we find in these woods an endless novelty and perennial freshness. The young swamp growth of red maple, white birch, and alder, bedded in grass and wild flowers, is very different from the dense young forest of birch and aspen of the northern woods that, under the influence of ample light, has sprung into being after some recent fire, the signs of which are still visible in the charred stumps under the young trees. The open groves of old oak and chestnut on the hill, with the slanting light of autumn and deep beds of dry, rustling leaves, are likewise different from the secluded forest in unfrequented mountains, where young and old growth mingle together: crooked ashes and moss-covered elms with straight young hickories, with shrubs and vines, and little seedlings sprouting among the rocks and mosses.

If we were to proceed in a continuous journey from the staid forests of the North to the more diversified growth of the intermediate States, and, going on, were to visit the complex forests of the South, we should notice only a very gradual transition. Yet if we were to study any particular region within these larger areas it would be found to have certain definite characteristics.

Let us imagine ourselves standing, for instance, on some point of vantage in the Blue Ridge of Virginia, the season being early May. The view extends across ranges of low, rounded mountains, which are fresh with the new foliage of spring. On the nearest hills the individual trees and their combinations into groups can be distinguished; but receding into the valleys and more distant slopes the forms and colors grow less distinct, till the tone becomes darker and at last melts into the familiar hazy blue of the distant hills. Looking again at the nearer hillsides, we recognize the tulip trees with their shapely crowns, clothed in a soft green and lifted somewhat above the general outline. The light green of the opening elms and sweet gums can be very well distinguished beyond the more shadowy beeches, ashes, and maples. The remaining spaces are occupied by hickories and chestnuts, still brown and leafless, and by rusty-hued oaks, which are only just beginning to break their buds. Within the leafless portions of the wood an occasional dash of bright yellow or creamy white, not quite concealed, shows where the sassafras or dogwood is in bloom. The crests and ridges, however, are likely to be occupied by groups and bands of pines, while the sides of the mountain brook will be studded with cedars and hemlocks.

In such scenery, if it be natural, there is no vulgarity and no faultiness of design. With all the variety there is still a fitness in form, color, and expression. It is rough, but pure in taste. For instance, the pine groves on the mountain ridges are not sharply defined in their margins and thus separated from the rest of the forest, but they gradually merge with the neighboring trees in a way that was naturally foreshadowed in the conformation of the land and the composition of the soil.

A feature so natural and self-evident may hardly appear worthy of notice; but its value is appreciated as soon as we compare the outlines referred to with the rigid forms of some of the artificial forests of Europe. Those who have seen the checkered forests of Germany, where the design of the planted strip of trees, like a patch upon the mountain, is unmistakable, will readily note the contrast between the natural and the artificial type. Neither is there any striving for effect in the natural forest, an error not uncommon in the tree groupings of parks or private estates. In these an effort is sometimes made to produce an impression by contrasts in form and color, but too often the outcome is mere conspicuousness; while nature, in some subtle way, has touched the true chord.

Forest scenery, however, need not be as extensive as this in order to add appreciably to the beauty of landscape. In the valley of southern Virginia, among the peach orchards and sheep farms, low hills lie scattered on both sides of the valley road. The mountain ranges beyond them recede to a great distance, and are partly hidden from view by these intervening hills. The latter, however, are decked with bits of woodland: groves of oak, chestnut, and beech, where the horseman on sunny summer days finds a welcome coolness and shade. Would these sylvan spots be missed if they were to be removed? They now exercise a beneficial influence on the drainage and moisture conditions of the surrounding farmlands, and they supply some of the home wants of the farmers. But they have an esthetic value also. They are usually in neat and healthy condition, and, viewed either from within or without, they are balm to the eyes as they lie scattered promiscuously over the hills.

It is hardly two hundred miles by road from that region to the high mountains of the North Carolina and Tennessee border, where we find broadleaf forests of the wildest and roughest kind. These happily still possess the great charm of undisturbed nature. The small mountain towns lie scattered far apart. The region is even bleak and dreary—at least until the summer comes; but when everything turns green the season is glorious. As we ride through these woods we realize the majesty of their stillness and strength, and cannot help admiring the great oaks and chestnuts that contend for the ground, succumbing only after centuries in the strife.

While the broadleaf forests of western North Carolina and eastern Tennessee are characterized principally by grandeur, this is not commonly a pronounced trait of the leafy forests. Rather are they distinguished for a certain air of cheerfulness, the expression of which will vary in different localities; but in some way it will manifest itself almost everywhere. Thus, in the southern half of New England woodland scenery is marked by a peculiar expression of quiet gladness. Whether it be in small farm woods among low hills, or in continuous forest, as in the Berkshires, there is the same happy choice in bright and cheerful trees: maples, birches, elms, and others; some bright with early spring blossoms, some adding to the variety of color by their bark or shining leaves, others agile of leaf and bough in the frequent breezes. Here we find an abundance of oaks, trees whose fresh, glossy leaves seem to be specially well fitted to purify the air, for there is a distinct and refreshing odor in oak forests. We find an ample choice of tender, springy plants among the moist rocks. These smaller woods, too, are the favored haunts of the songbirds, for here they find the glint of sunshine that they so much delight in.

A similar warmth of expression belongs to the leafy woods of other regions. If we compare New England with Pennsylvania, we shall find that the broadleaf forests of the latter are denser and more continuous, while they are at the same time richer in the variety of trees, shrubs, and other forms of embellishment, which find here a milder air and a richer soil. Springtime is more luxuriant and replete with happy surprise and change. But while these forests are perhaps more elaborate than those of southern New England, I cannot say that they impress me as being so homelike and engaging.

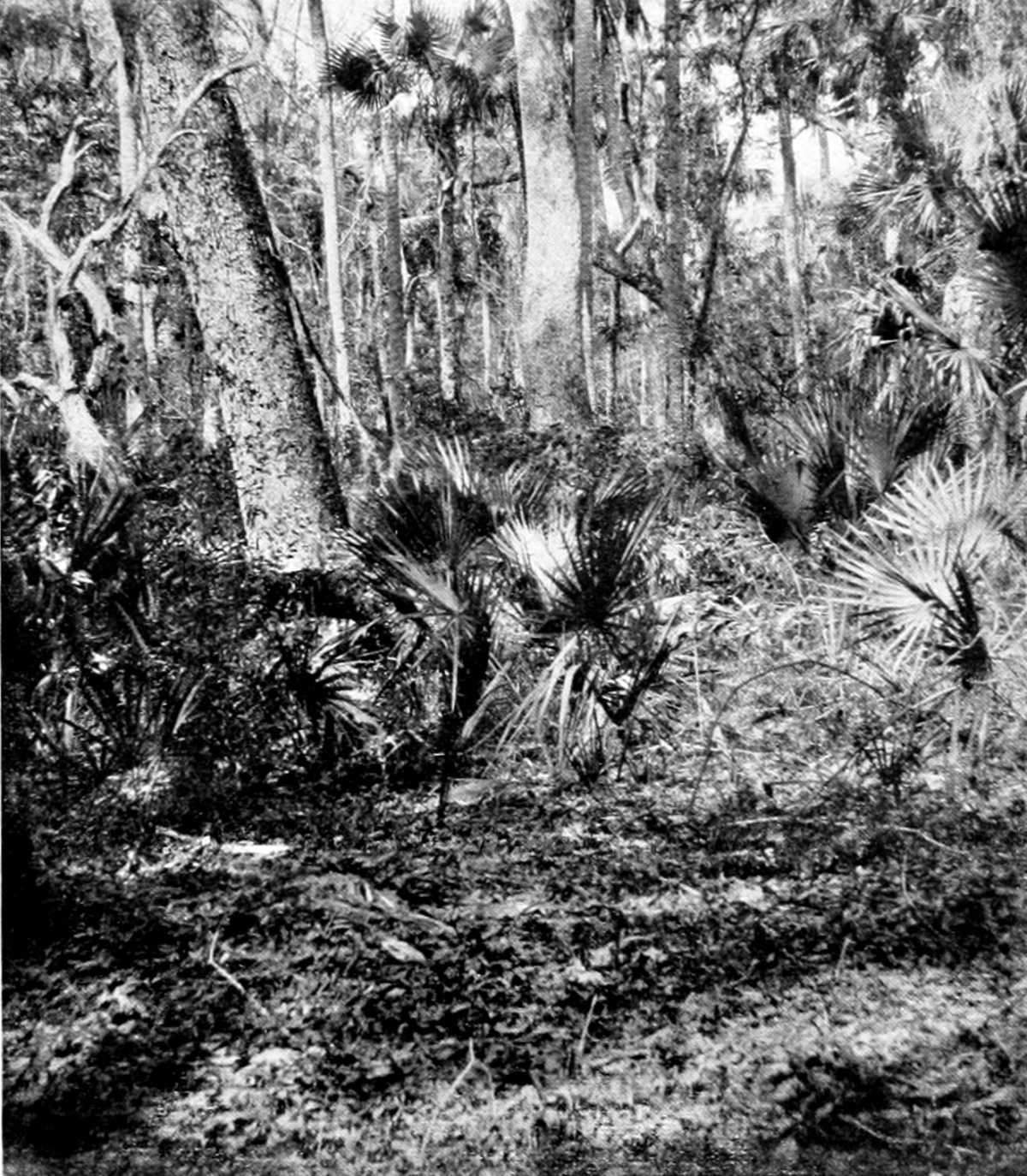

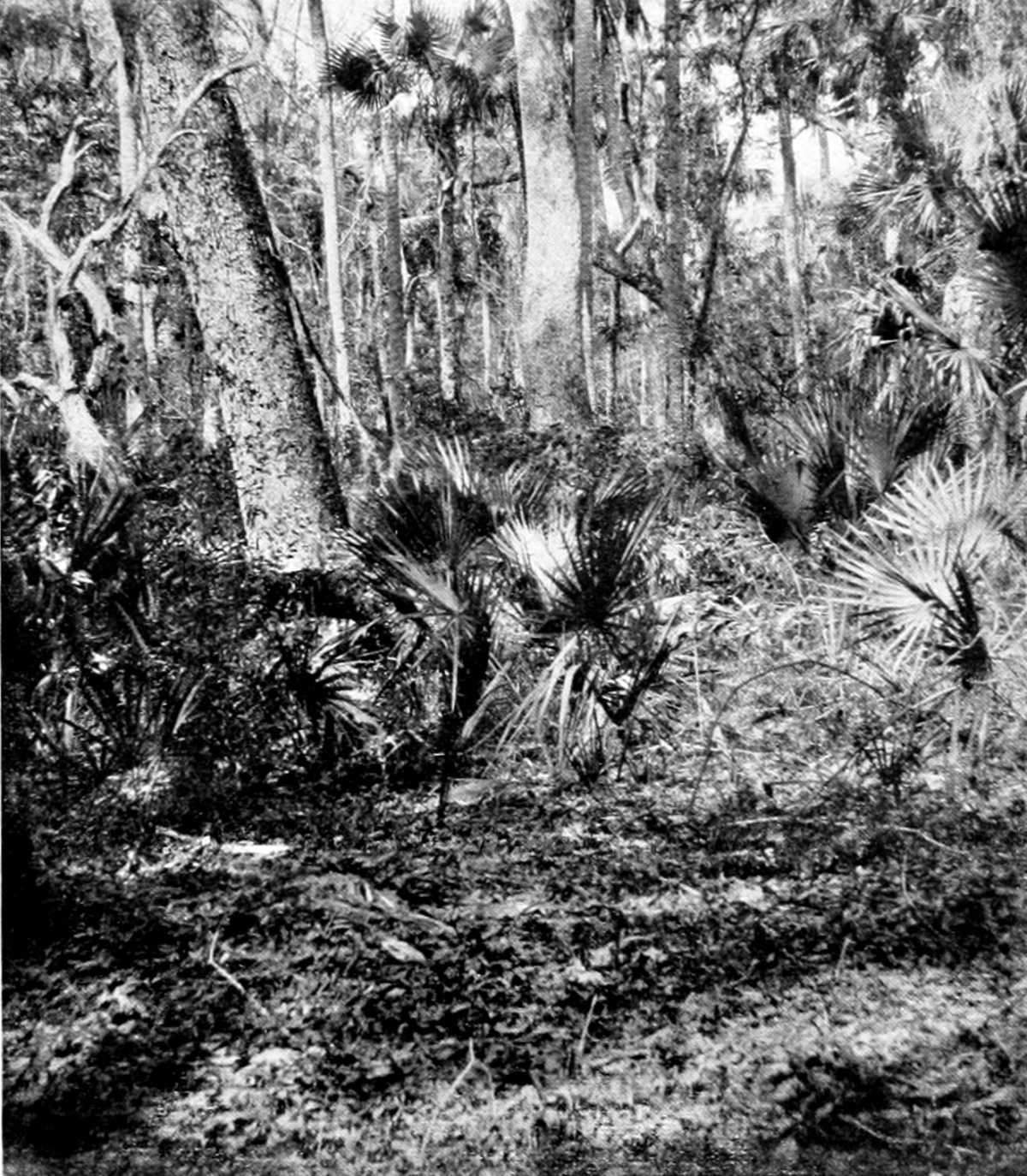

Along the Gulf and in Florida the dank forests of the swamps and river bottoms, finding all the conditions favorable to a luxuriant vegetation, are characterized by extraordinary complexity of growth. Perhaps we enter some secluded patch of virgin forest, and sit down for a while in its dense shade, impressed by the strangeness and solitude of the place. Our curiosity is aroused by the multifarious assemblage of trees, vines, and shrubbery, and we wonder how many ages it has been thus, and how far back some of the oldest trees may date in their history. But they seem rather to have no age at all; only to be linked in some mysterious way with the dim past out of which they have arisen.

Virgin Forest Scene in Florida

A mighty live oak leans across the scene, moist and green with moss; another is noticed farther away among slender palmettos, whose spear-edged leaves catch the sunlight. Vines and climbers hang about the stems or droop lazily from the boughs. In the nearby sluggish water, where the soil is deep and moldy, stands a sweet gum with curiously chiseled bark, as if some patient artist had been at work; and a little beyond, some cypresses are roofed by the delicate web of their own foliage.

We may sit dreaming away a full hour thus, with only the hum of a few insects and perhaps a stray scarlet tanager flitting by to disturb our meditations.

It has been indicated in a former chapter that the broadleaf woods, taken as a whole, are decidedly richer in shrubs and small plants than the evergreen or coniferous forests. This adventitious source of beauty has much to do with their general character, because the gay show of blossom and fruit, bright stem, and diverse habits of growth of these lesser plants, contributes appreciably to the liveliness of sylvan scenery. But the effect derived from the blossoms and fruits of many of the trees themselves should not be overlooked. In this respect the broadleaf trees are superior to the evergreens. The poplars and willows ripen their woolly and silvery tassels when the snow has scarcely disappeared. The bright tufts of the red maple, the little yellow flowers of the sassafras, the snowy white ones of the serviceberry and flowering dogwood, the latter’s red berries in fall, the brilliant fruit of the mountain ash, the perfect flowers of the magnolias, the heavily clustered locusts, honey locusts, and black cherries, and the basswoods with fragrant little creamy flowers, alike do their part in lending character to the forest wherever they may have their range.

Then, in addition to the beauty that appeals to us through the outward senses, there is a quality in the forests that is dear to us through an inward sense. It is the influence of a temperament that seems to belong to the place itself: the pure and health-giving atmosphere, the quiet and rest that binds up the wounded spirit and brings peace to the troubled mind.

We leave the turmoil of the city and the thousand little cares of daily life and seek refuge for a while in sylvan retreats, in some pleasant leafy forest with murmuring water and sunbeams; and presently the ruffled concerns of yesterday are smoothed away and the forest, like sleep, “knits up the raveled sleeve of care.”

In the woods there is harmony in all things; all things are subordinated to one purpose and desire: that the best may be made out of life, however small the means. There is a kind of honesty and truth here, and a self-sufficiency in everything. Shakspere says, in the words of Duke Senior, who stands surrounded by his followers in the Forest of Arden (“As You Like it,” act ii, scene 1):—

Are not these woods

More free from peril than the envious court?

Here feel we but the penalty of Adam,

The seasons’ difference; as, the icy fang

And churlish chiding of the winter’s wind,

Which, when it bites and blows upon my body,

Even till I shrink with cold, I smile, and say,

“This is no flattery: these are counselors

That feelingly persuade me what I am.”

* * * * * *

And this our life, exempt from public haunt,

Finds tongues in trees, books in the running brooks,

Sermons in stones, and good in everything.