V

THE CONIFEROUS FORESTS

IT has already been said that the evergreen or coniferous forests differ from those described in the foregoing chapter by a denser community of growth and by their frequent occurrence as “pure” forests. Their gregariousness makes it proper to apply such expressions as the “pine forests of Michigan” and the “spruce forests of Maine.” It will be seen presently that these special characteristics are esthetically important. Moreover, it is a fact that they borrow much grandeur and beauty from the atmospheric conditions of their environment, which, if we except certain large tracts of pine forests, is commonly placed among mountains and at considerable elevations above the sea. To these several sources must be ascribed many of the qualities that have invested the evergreen forests with a peculiar magnificence and beauty.

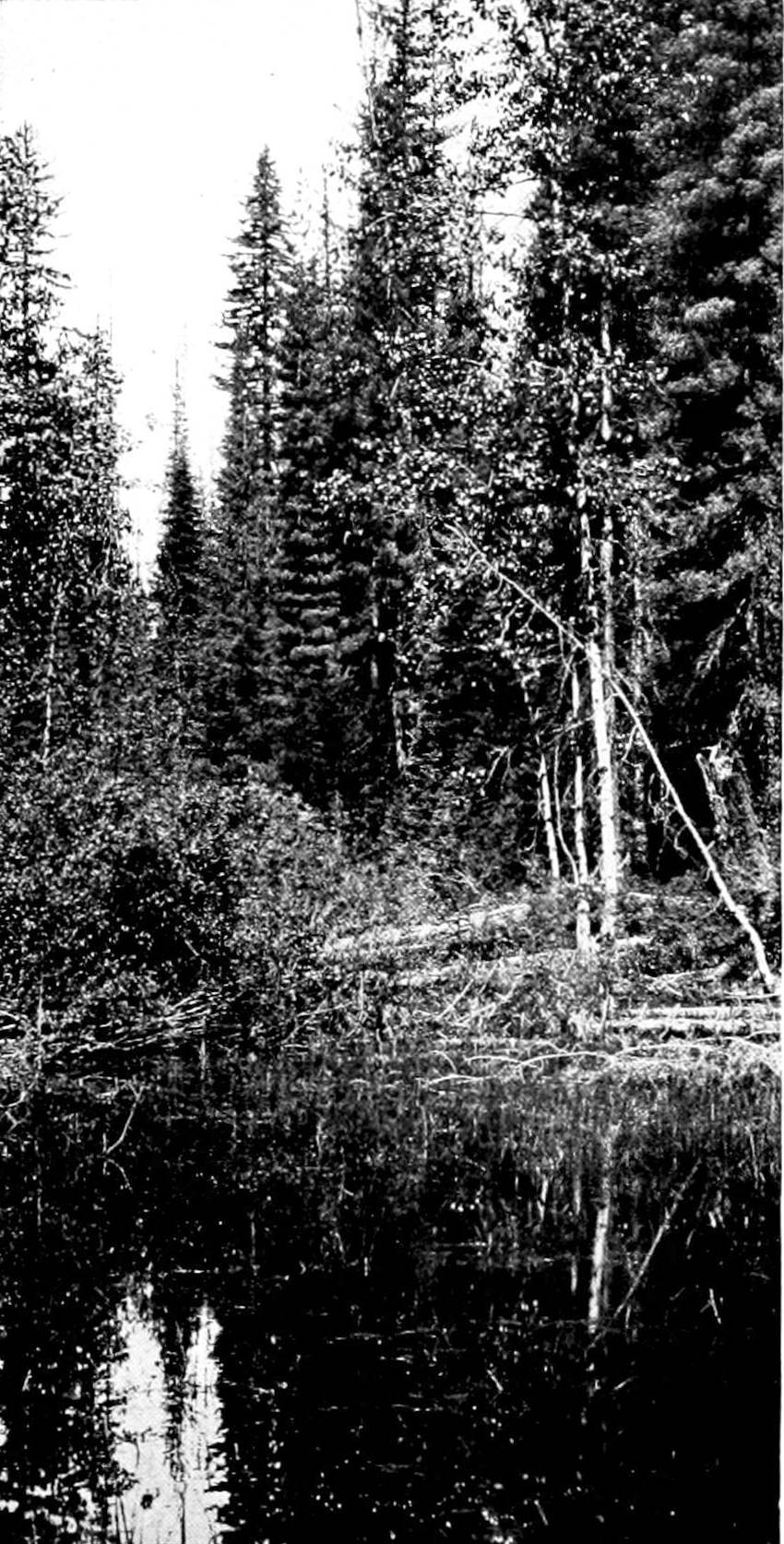

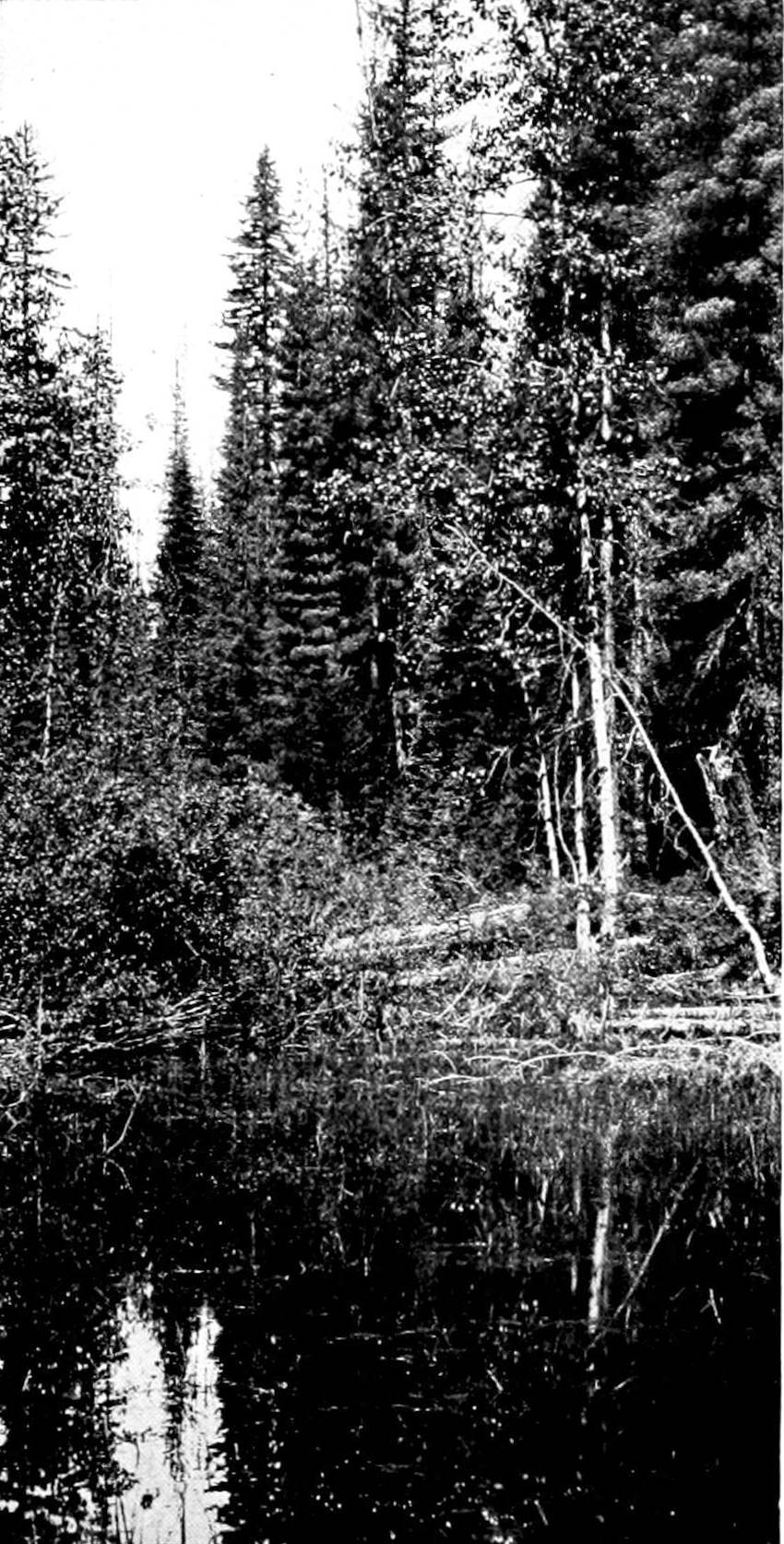

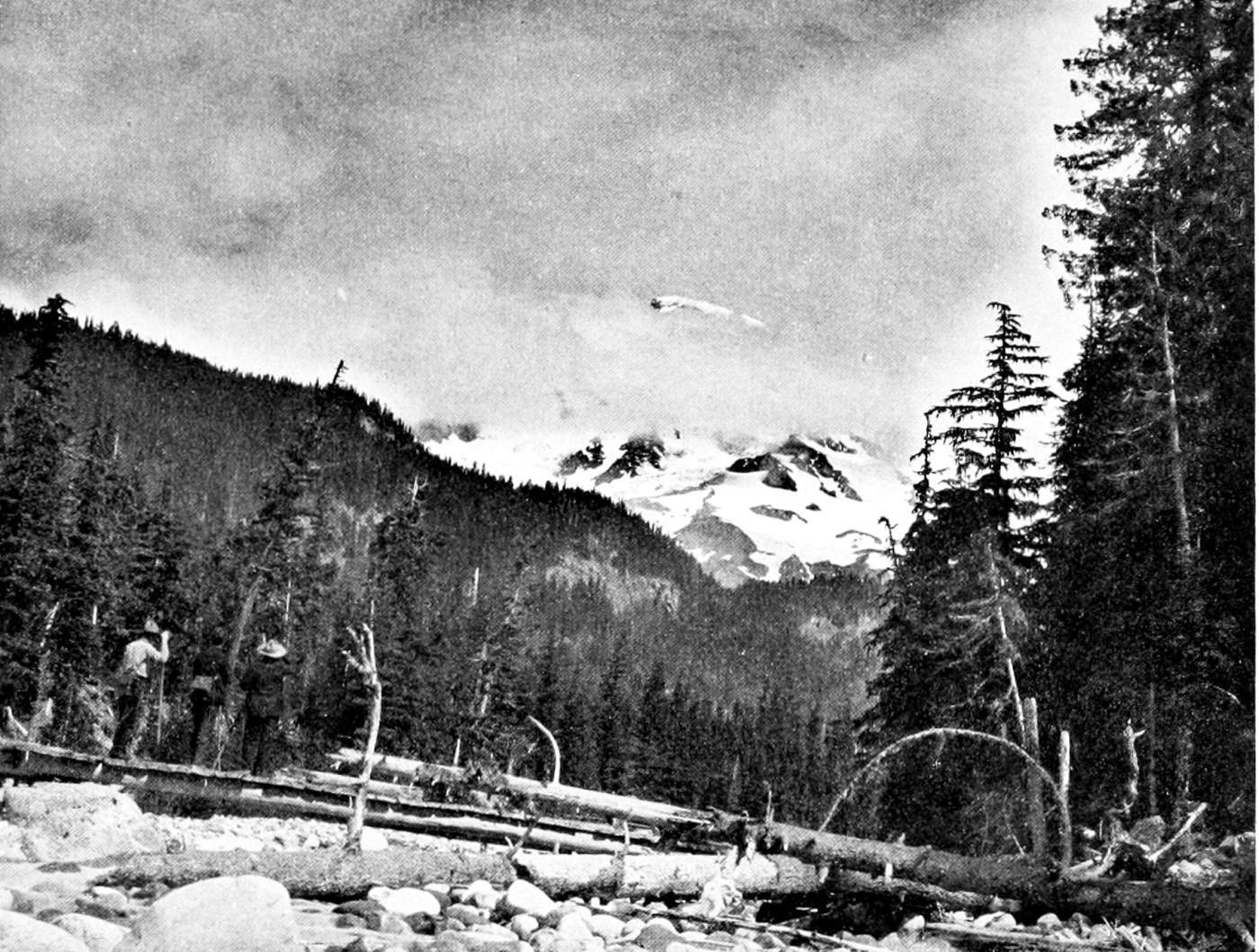

Courtesy of the Bureau of Forestry

A Group of Conifers. Montana

The reader may be surprised at the statement that coniferous forests are distinguished for a “dense community of growth,” for it must have been noticed that many of our Rocky Mountain forests do not bear evidence of this fact. And yet it is true that the typical habit, so to speak, of the conifers is a close huddling together of individuals. It is shown in the massive red fir forests of western Washington and the redwoods of California, which are probably the densest and heaviest in the world; in the crowded Engelmann spruce and alpine fir groves common to certain soils and situations in Colorado; and in the dense tracts of lodgepole pine scattered throughout the mountains of the West. In the East the same tendency is illustrated by the better sections of the Adirondack spruce forests and the splendid pineries that once covered the Great Lake region. If we call to mind these extensive examples, we realize how the conifers ever strive to build a dense and impenetrable forest. That they are capable of a like growth in other parts of the world also, will be attested by those who have seen the spruce and fir forests of Germany and France.

While the regions that have just been mentioned exhibit the health and vigor of coniferous forests under favorable natural conditions, there are certain portions of the Rocky Mountains where the climate is too dry and the topography and soil are too austere and rocky to suit even that hardy class of trees. So here, under circumstances that may almost be pronounced abnormal for forest growth, the evergreens fight a harder battle, while the broadleaf trees, with the exception of the poplar tribe, are scarce indeed. We must, therefore, turn to the more typical coniferous forests that have enjoyed at least a fair share of nature’s gifts—whether it be within the range of the Rocky Mountains or elsewhere—to understand those peculiar qualities that are connected with their surroundings or their characteristic habits of growth.

One of the commonest attributes of such forests is their grandeur; partly inherent and in part also derived from the sublimity of their surroundings. Their situation is often in the midst of wild and picturesque mountain scenery, where they find a proper setting for their own majestic forms among crags and precipices and on the great shoulders of mountains; where powerful winds and severe snows test their endurance and strength. It is here that we chiefly find those awe-inspiring distant views that harmonize so well with the evergreen forests. The trees spread over the mountains for miles and miles in closely fledged masses, and become more impressive with distance as the color changes from a continuity of dark green to shades of blue and soft, distant purple. In form and color the trees blend together and seem to move up the dangerous slopes and difficult passes in mighty multitudes.

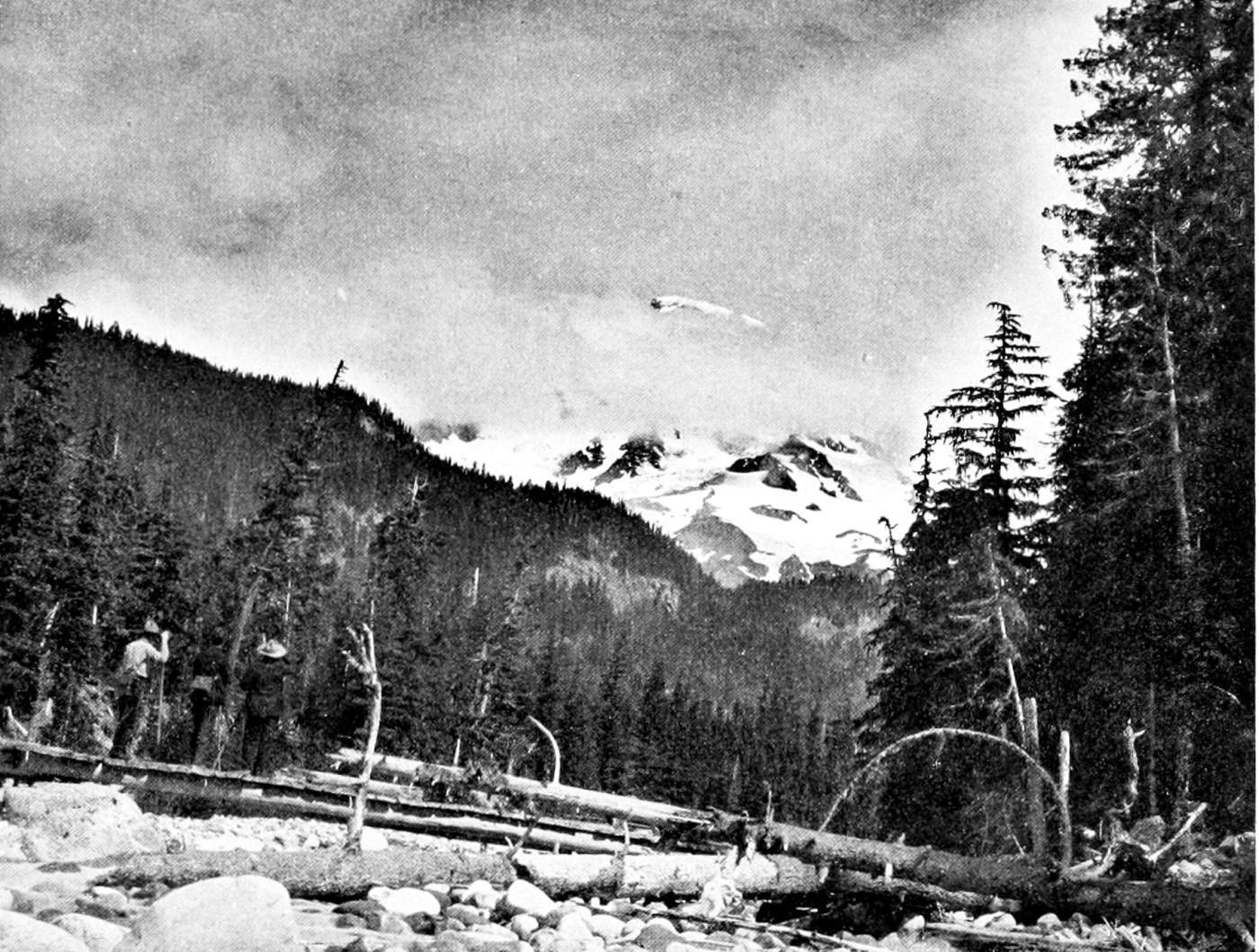

Courtesy of the Bureau of Forestry

Mount Rainier. Washington

Contributing to the same impression of grandeur, we have the possibility in these lofty regions of certain glorious effects in sunlight and shade. At sunrise the first rays flash on the pointed tops of the uppermost trees, and with the advancing hours descend the dark slopes on their golden errand. Meanwhile the western sides lie in shadow. At noon a soft haze spreads through the valleys, and in the twilight hours the intense depth of purple in the distant ranges, where stratus clouds catch the last rays of the sun, obscures the contours of the forests and makes them even more sublime. This, too, were not possible without great mass and uniformity of aspect.

The interchange between lights and shadows cast by the moving clouds is nowhere so effectively exhibited as in higher altitudes and over the surfaces of evergreen forests. A wide expanse enables us to follow with our eyes the interesting chase of the cloud shadows, as they fly up the slopes, the steeper the faster, and glide noiselessly but swiftly over outstretched areas of endless green. The clouds seem to move faster over mountain ranges, as a rule, than they do over the low valleys. Or is it only because now we see them nearer by and can gage the rapidity of their flight?

Suppose, instead of a restless day, it should be calm, with cloud masses heaped in the sky and the sun sinking low. There has been a loose snowfall in the afternoon, and every twig, branch, and spray hangs muffled in snow. The rocks are capped with a light cover and ribbed with snowy lines along their sides. The air is pure and breathless. The disappearing sun sends back a rosy light to the canopy of clouds overhead, and the reflection falls upon masses of frosted, whitened evergreens, lending them a breath of color that deepens as the sun sinks lower still; and the rays enter the openings of the hills and flood the opposite slopes, till they glow with a fiery red.

Thus the grandeur of these forests may be due to expanse and volume, depth of color, sunlight and shade, or to effects borrowed from the clouds. Finally, we notice another kind of grandeur when coniferous forests are visited by storms. First comes the moaning of the wind, mysterious and unsearchable, and different from the roar and rush that sweeps through the broadleaf woods. Then follows the uneasy communication from tree to tree, a trembling that spreads from section to section. When the rush of the wind finally strikes the tall, straight forms they do not sway their arms about as wildly as do the maples, elms, or tulip trees, but bend and sway throughout their length and rock majestically.

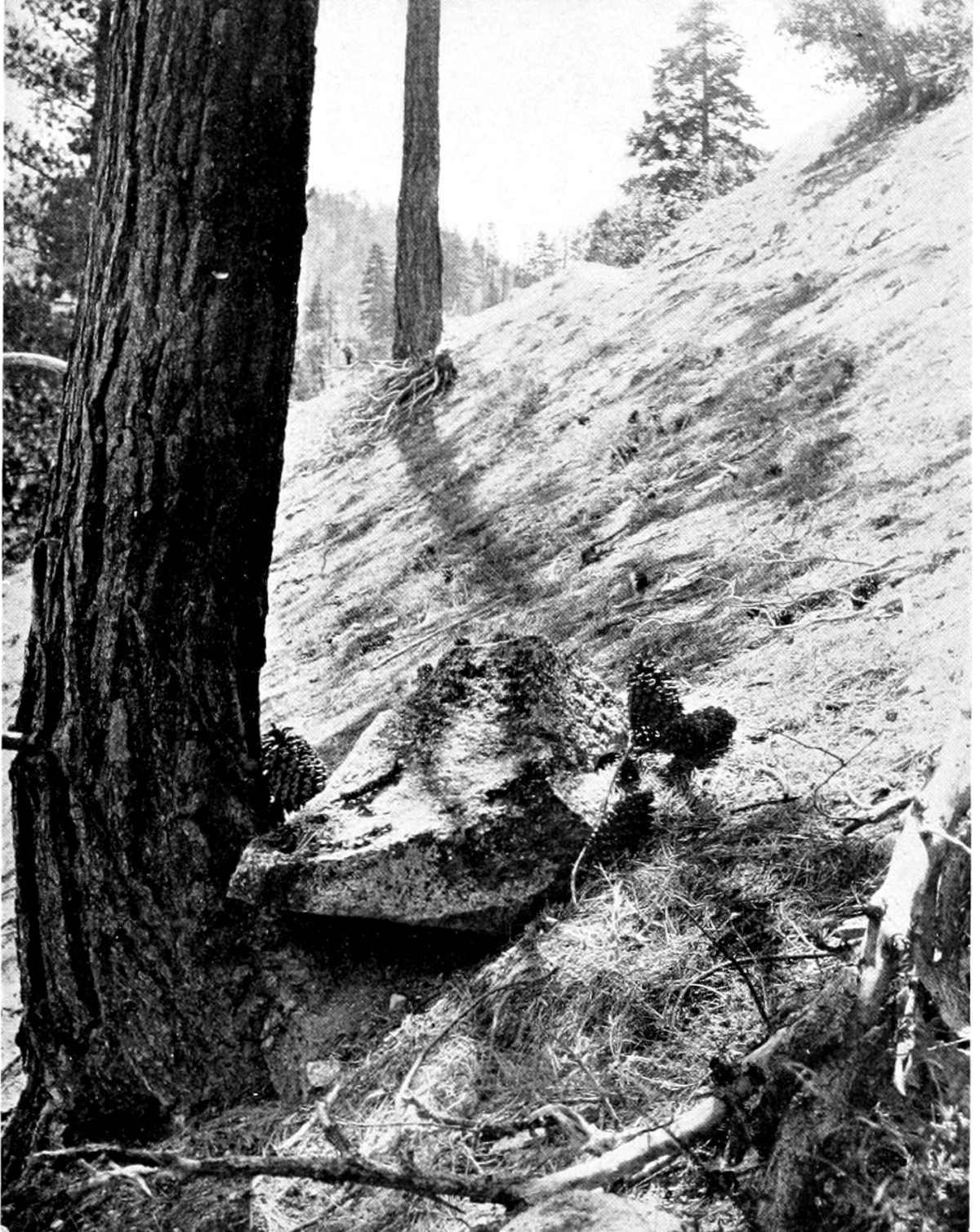

A Thicket of White Firs

Not in outward aspect alone are these forests noble and stately. A nobleness lies in the nature of the living trees themselves; for, though we may call them unconscious, it is life still, and they are expressive with meaning. Far simpler in their habits and requirements than the broadleaf trees, they are, nevertheless, more generous to man. Endurance and hardship is their lot, but noble form of trunk and crown and useful soft wood are the products of their life. There is no forest mantle like theirs to shield from the blast, especially when it is formed of young thickets of the simple but refined spruces and firs. When, at the last, they yield their life to man, it seems to me there is something exalted even in the manner of their fall. The tree hardly quivers under the blows of the ax; a mere trembling in the outermost twigs, and then, hardly as if cut off from the source of life, the tall, straight form sinks slowly to the earth.

Another common attribute of evergreen forests is their characteristic silence. Birds do not frequent them as much as the leafy forests. In these solitudes, far removed from village and farm, there is often no sound but the ring of the distant ax and the sough of the wind. In winter, as we push through the thickets of small spruces or hemlocks, or stand for a while beneath lofty pines, while all around is muffled in snow, the silence seems sanctified and vaster than elsewhere.

In addition to their grandeur and sublimity, and their silence, they are distinguished for an element of softness. This is seen in the delicate texture and pure color of their foliage, the effect of which is heightened by being massed in the dense forest. We have already noticed the mild olive shade of the eastern white pine. When the wind blows through it, it seems as if the foliage were melting away. It would be difficult, also, to match the green color of the red fir, especially as it looks in winter; or the luxuriant bluish-gray of the western blue spruce.

A further softening in the general effect of evergreen forests is produced by the manner in which the trees intermingle in the dense mass, merging their sharp, individual outlines in the rounded contours and upper surfaces of the combined view. Near at hand, of course, we cannot but notice the attenuated forms and jagged edges of the trees, which, indeed, are interesting enough in themselves; but on looking gradually into the distance we find them thatching into one another, closing up interstices and smoothing away irregularities in a remarkable way. This is particularly true of the spruces and firs; but in some of the opener pine forests, as, for example, in the longleaf pines of the South, the boughs and crowns themselves are rounded into masses and pleasing contours. It should be remembered, also, that these effects are present in winter as well as in summer.

The element of softness is sometimes brought into very beautiful association with certain effects of mists and clouds. The indistinct contours and delicate lights of the drifting vapors and cloud forms, as they wander across the trees, blend with the serene aspect of the forest. At other times the clouds gather into banks and lie motionless in some valley or rest like a veil upon the mountain tops. Wordsworth has described these effects in his graphic way by saying,—

Far-stretched beneath the many-tinted hills,

A mighty waste of mist the valley fills,

A solemn sea! whose billows wide around

Stand motionless, to awful silence bound:

Pines, on the coast, through mist their tops uprear

That like to leaning masts of stranded ships appear.

In spring or summer just before sunrise it is very beautiful to see how these banks of vapor are lifted by the stirring airs of the dawn, how the draperies of mist draw apart and open up vistas of the trees, which drip with moisture, and are presently illumined by the broad shafts of sunlight that pour down upon them.

Lest it be thought that only the dense coniferous forests possess superior qualities, I desire to put in a plea for the open ones also.

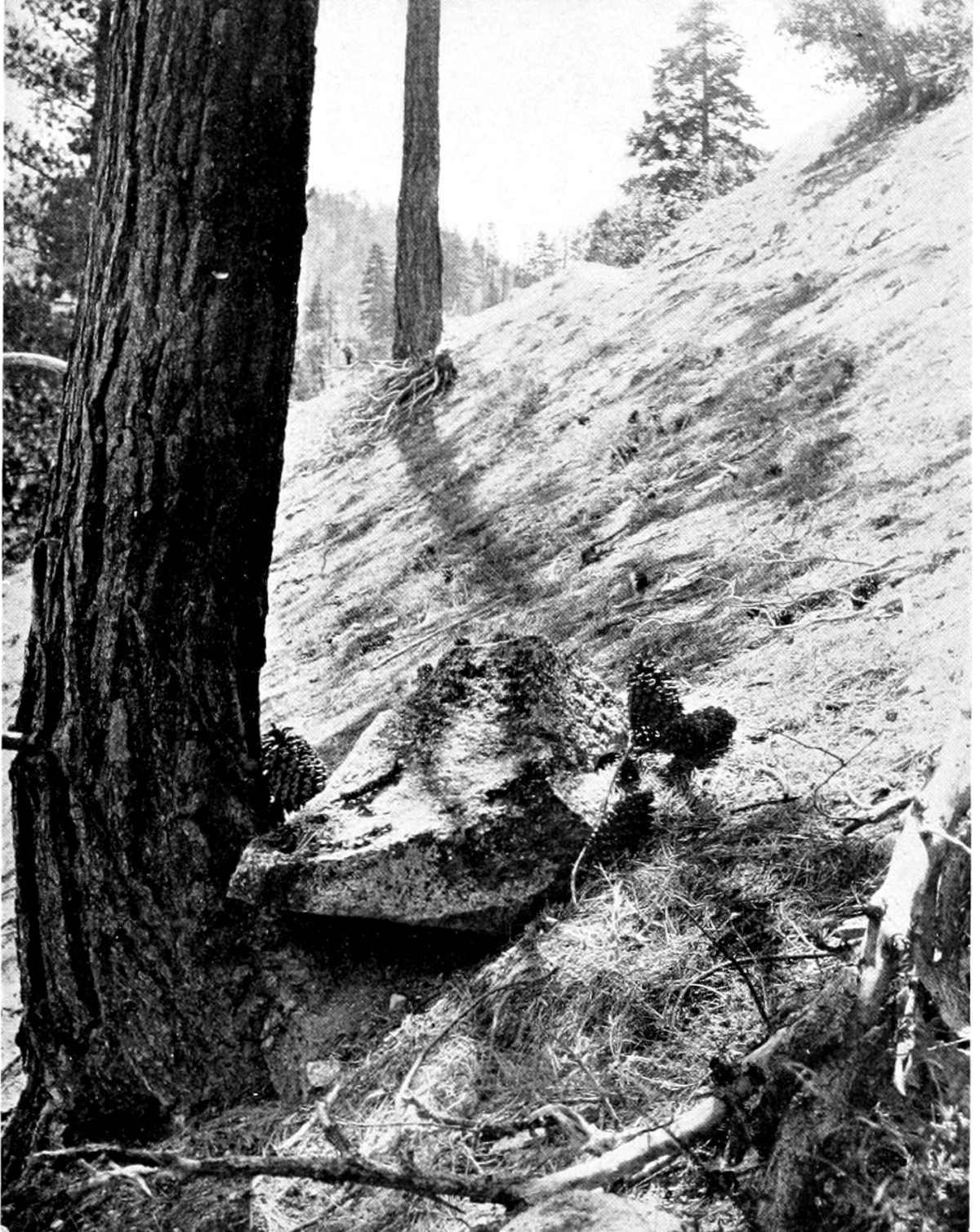

Courtesy of the Bureau of Forestry

An Open Forest in the Southwest

It is a universal truth in nature that when a living thing has made the best possible use of its environment, when the power within has been sacrificed and united to the circumstances without, there is evolved a dignity of character and a resulting expression of fitness and beauty. This principle is exemplified in the very open forests of the Southwest. In the mountain ranges of New Mexico, Arizona, and southern California the forests have a hard struggle for existence. The winter months at the higher elevations are severe; in the summer rain is scarce, or entirely absent, and the sun beats down upon the dry earth through the rarefied atmosphere with intense and desiccating power. Naturally the forest trees are scattered, and on the steep, crumbly slopes, dry and rocky, they hug the soil and cling to it with uncertain footing. But in a sheltered ravine, or on the back of a rounded ridge, or in a slight swale or hollow of the mountain—repeatedly, in fact, among those rugged slopes—we meet with the dignity, the beauty, and the peculiar expressiveness of the open coniferous forest, with its fine definition and stereoscopic effects and the depth and perspective of its long vistas.

On the crest of the mountain, where, from the valley below, the early sunlight is first seen to break through, the trees, standing apart, do not appear so much like a forest as like a congregation of individuals, each with an identity of its own. Indeed, there among the fierce gales of autumn and winter each shapes its own life in a glorious independence, expressive in the knotty, twisted boles and the picturesque crowns. But in summer the breezes strain through the foliage with the lethargic sound of the ocean surge; or a halcyon stillness reigns under a deep blue, cloudless sky.

A Storm-beaten Veteran

Large old trees, these, with a history, that have braved life together. They have seen companion veterans fall by their side, long ago, into the deep, closely matted needle-mold. Thence arose out of the moister hollows beneath the rotting trunk and boughs a new generation, and the greater number of these have disappeared, too, for some reason or another; only the strongest at last leading, to take the place of the departed. How dignified, how simple are these old, stalwart trees on the exposed ridge of the mountain.

Thus the coniferous forests, by virtue of their inherent qualities and by means of the effects they borrow from their environment, possess a tone that is as original and distinct as the character of the forests belonging to the other class. It has already been intimated that the two are not always strictly separable, but that individual trees, or groups, or whole stretches of woods of the one will sometimes mingle with the other, a fact that has probably been noticed by the most casual observer. While the cone-bearers, however, not infrequently descend into the lower altitudes, the leafy forest trees are not so apt to be found at the high elevations at which many of the former find their natural home. Where the cone-bearers are merely an addition to the broadleaf woods they do not quite preserve their identity, but rather impress us as being merely a part in the general adornment and composition of the forest to which they belong. Where they remain “pure,” however, as they do, for instance, in the pineries of the coastal plain in the South, they never fail to express, in one or another manner, their individuality as a forest; as by their uniformity in size and color, by their odor, or by the scenic character of the region of their occurrence.

All the preceding qualities of coniferous forests practically address themselves in some manner to our physical senses. But, like the broadleaf forests, these also possess a trait that rather addresses itself to our mood or personal temperament. A characteristic air of loneliness and wild seclusion belongs to them that contrasts strikingly with the cheerful tone of the other class. It has been commonly remarked that to some kinds of people the coniferous forests are oppressive, at least on first acquaintance. Such natures feel the weight of their gloom and lose their own buoyancy of spirit if they stay too long within their confines; and it is noticeable that even the inhabitants of these lonely retreats are not infrequently affected with a reticence and a kind of melancholy that impresses the stranger almost like a feeling of resignation. This peculiar temperament, however, may be judged too hastily, and is understood better after a time. It is probably true that the familiar and accessible woods of valley and plain, where trails and wood-roads give us a feeling of security, are more attractive and agreeable to most of us; yet there is a wonderful charm about those dark forests of the mountains that have grown up in undisturbed simplicity. After the first feeling of strangeness wears off, as it soon will, they grow companionable and interesting. There is a virtue in the sturdy forms that have grown to maturity without aid or interference by man. We would not change them in that place for the most beautiful trees in a park. Even the woodsman, whose days are spent here in the hardest toil, feels a longing for the forest, his home, when his short respite in the summer is over. So we, too, though we may long for civilization after a few months in the forest, will yet feel the desire to return to it after once thoroughly making its acquaintance.

The attitude of the woodsman toward the forest is much like the affection which the sailor has for the ocean. There is, indeed, a similarity between their callings, and even the elements in which they pass their lives are not so dissimilar in reality as may appear on the surface. In his vast domain of evergreen trees that cover mountain and valley, the woodsman, too, is shut out from the busier haunts of men. He lives for months in his sequestered camp or cabin, where his bed is often only a narrow bunk of boughs or straw. His food is simple and his clothing rough and plain, to suit the conditions of his life. A large part of the time he is out in snow and rain, tramping over rough rock and soil. The camps that are scattered through the forest are to him like islands, where he can turn aside for food and rest when on some longer journey than usual.

Like the sailor he also has learned some of the secrets of nature. He does not usually possess a compass, but he can tell its points by more familiar signs: by the pendent tops of the hemlocks, which usually bend toward the east, or by the mossy sides of the trees, which are generally in the direction of the coolest and moistest quarter of the heavens. In an extreme case he will even mount one of the tallest of the trees to find his bearings in his oceanlike forest. If well judged, the sighing of the wind in the boughs, I have been told, says much about the coming weather; just as the sickly wash of the waves means something to the sailor. Withal, both he and the woodsman are natural and generally honest fellows, hard workers at perilous callings, and less apt to speak than to commune with their own thoughts.