I

FOREST TREES

THE beauty of a forest is not simple in character, but is due to many separate sources. The trees contribute much; the shrubs, the rocks, the mosses, play their part; the purity of the air, the forest silence, the music of wind in the trees—these and other influences combine to produce woodland beauty and charm. A first consideration, however, should be to know the beauty that is revealed by the trees themselves.

Here it will be wise to make a selection: to choose out of the great variety of our forest flora those trees that most deserve our attention. Many of our forest trees have naturally a restricted range; others are narrowing or widening their range through human interference; still others have already established their right to a preëminence among the trees of the future, because, possessing to an unusual degree the qualities that will make them amenable to the new and improved methods of treatment known as “forestry,” they are certain to receive special care and attention; while those that are not so fortunate will be left to fight their own battles, or may even be exterminated to make room for the more useful kinds. Among all these the rarest are not necessarily the most beautiful. Those that are commonest and most useful are often distinguished for qualities that please the eye or appeal directly to the mind.

In accordance with the ideas already expressed in the Preface, the considerations that will determine what trees shall be described are as follows: first, trees of beauty; next, those that are common and familiar; finally, those that are important both for the present and the future because they are useful and have an extended geographical distribution.

The trees selected for description will here be divided into the two conventional groups of broadleaf species and conifers, beginning with the former.

THE BROADLEAF TREES

In the “Landscape Gardening” of Downing we read concerning the oak,—

“When we consider its great and surpassing utility and beauty, we are fully disposed to concede it the first rank among the denizens of the forest. Springing up with a noble trunk, and stretching out its broad limbs over the soil,

‘These monarchs of the wood,

Dark, gnarled, centennial oaks,’

seem proudly to bid defiance to time; and while generations of man appear and disappear, they withstand the storms of a thousand winters, and seem only to grow more venerable and majestic.”

It would be difficult to say whether Downing had any particular species of oak in mind when he wrote these words. The common white oak and the several species of red and black oak possess in an eminent degree the grandeur and strength which he describes and for which we commonly admire the tree.

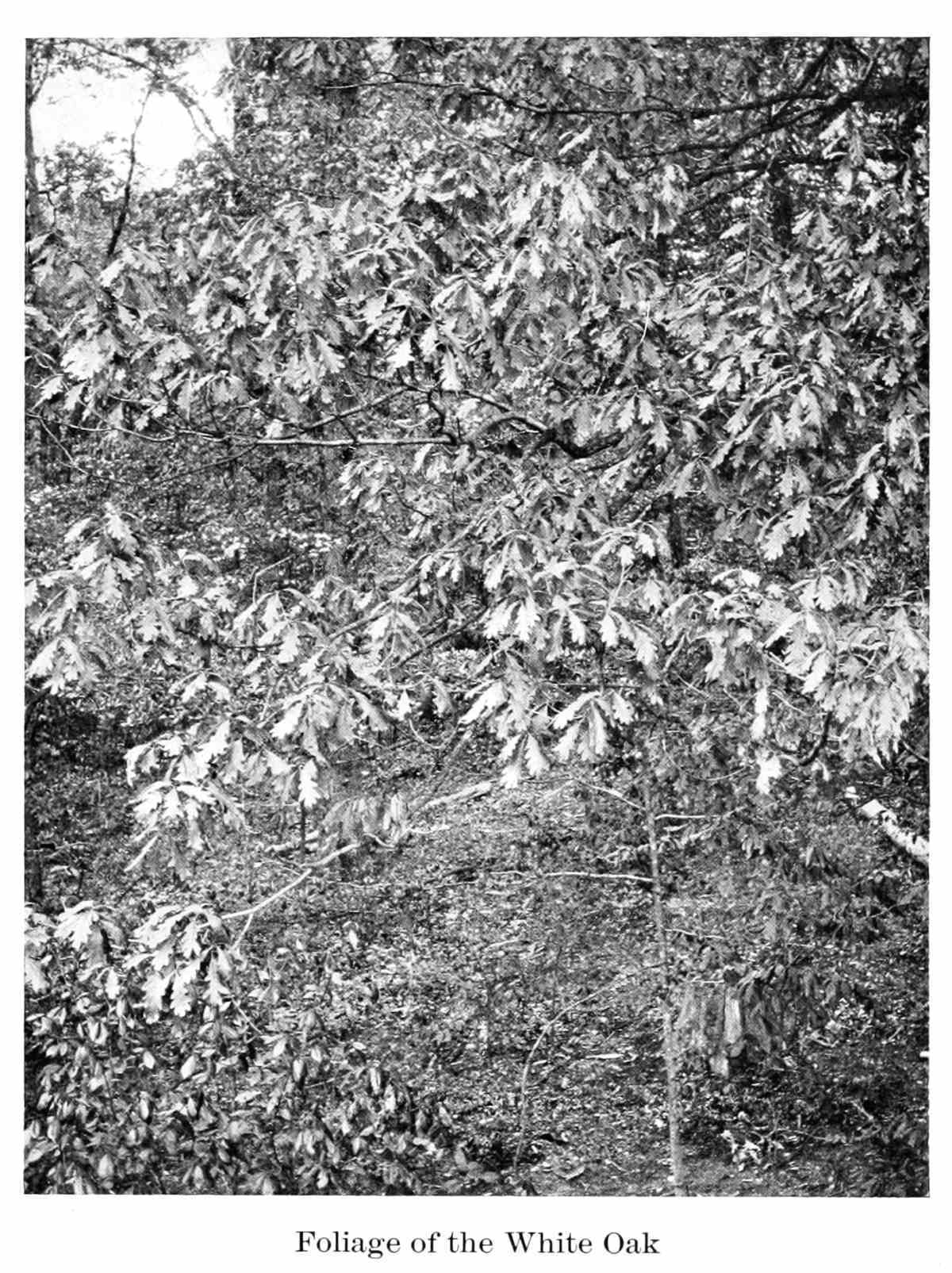

Of all the oaks[1] the white oak is the most important. This tree will impress us differently as we see it in the open field or in the dense forest. Where it stands by itself in the full enjoyment of light, it has a round-topped, dome-shaped crown, and is massive and well poised in all its parts. Quite as often, however, we shall see it gathered into little groups of three or four on the greensward of some gently sloping hill, where it has a graceful way of keeping company. The groups are full of expression, the effect is diversified from tree to tree, yet harmonious in the whole. In the denser forest the white oak often reaches noble proportions and assumes its most individual expression. There it mounts proudly upward, contending in height at wide intervals with sugar maples and tulip trees, its common associates in the forest. Its lofty crown may be seen at a distance, lifted conspicuously above the heads of its neighbors. Stand beneath it, however, and look up at its lower branches, and there is revealed an intricacy of branchwork and a tortuosity of limb such as is unattained when it stands alone in the field. The boldness with which the white oak will sometimes throw out its limbs abruptly, and twist and writhe to the outermost twig, I have never seen quite equaled in the other oaks. The live oak, it must be admitted, is even more abrupt where the limb divides from the trunk, but it does not continue its vagaries to the end.

It is to be noted that these forms are not without a purpose and a meaning. Under difficulties and obstacles the twigs and branches have groped their way; often one part has been sacrificed for the good of another, in order that all gifts of air, and moisture, and light might be received in the fullness of their worth. Thus the entire framework of the tree becomes infused with life and meaning, almost with sense, and its character is reflected in its expression.

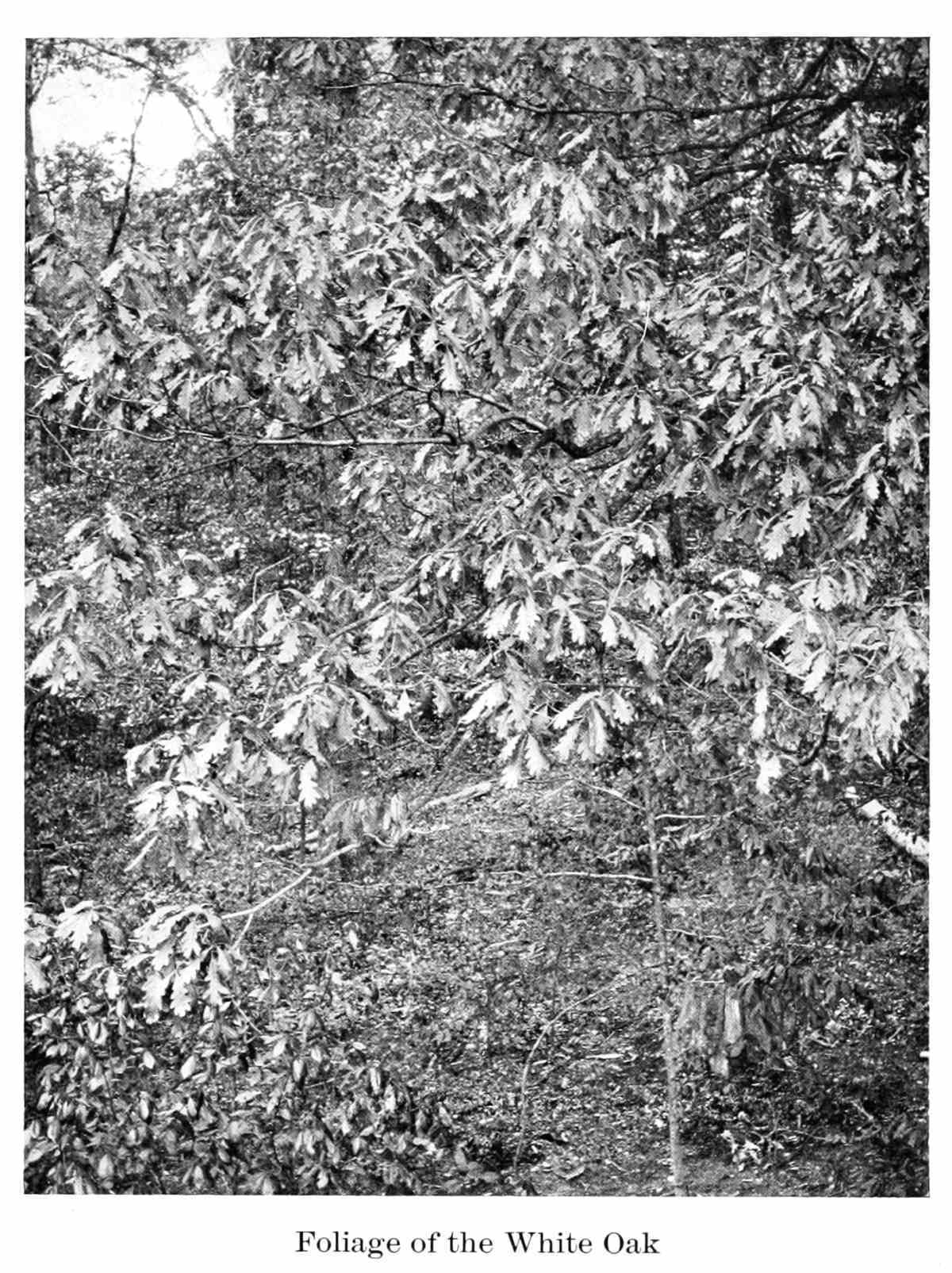

The observer is also impressed by the character of the foliage. The leaves are usually rather blunt and ponderous, varying a little—as, indeed, do those of several other trees —according to the nature of their environment. They clothe the tree in profusion, but do not hide the beauty of the ramification of its branches. In truth, they are not devoid of beauty themselves. It was natural for Lowell to exclaim,—

A little of thy steadfastness,

Rounded with leafy gracefulness,

Old oak, give me.

While the leaves of the white oak do not deflect and curve as much in their growth as those of some of the more graceful and elegant trees, they nevertheless fall into natural and pleasing groups, unfolding a pretty variation as they work out their patient spiral ascent, leaf after leaf, round the stemlet; showing a changefulness in the sizes of the several leaves, and a choice in the spacing. In the first weeks of leafing-time there is to be added to these features the effects derived from transitions of color in the leaves. For the very young leaves are not green, but of a deep rose or dusky gray. They are velvety in texture, and lie nestling within the groups of the larger green leaves that have preceded them. Just as it was said a little while ago that there was expressiveness throughout the branches, it may now be said that there is a fitness of the foliage for all parts of the tree.

Foliage of the White Oak

In winter, however, the beauty of the oak’s foliage is gone. The dry leaves still hang on the boughs, sometimes even until spring, but they look disheveled and dreary. Still, they are not without some esthetic value, though it be through the sense of hearing instead of sight. Thoreau says,—

“The dry rustle of the withered oak-leaves is the voice of the wood in winter. It sounds like the roar of the sea, and is inspirating like that, suggesting how all the land is seacoast to the aërial ocean.”

Deep and glorious, too, is the light that rests in the oak woods on midsummer days. It filters, softened and subdued, through the wealth of foliage, and wraps us in a mellow radiance. Its purity and calm depth lift the senses to a higher level. Most limpid is the light in a misty shower, when the sun is low and the level rays break through the moist leaves and dampened air, while we stand within and see everything bathed in a golden luster.

Our common chestnut is of less economic value than the oak, but one suggests the other, for the two are often found together and are similar in size and habit. The chestnut is, in truth, one of our finest deciduous trees. It has a luxuriance of healthy, dark-green foliage, and is happy-looking in its abundance of yellow-tasseled blossoms. It is even more beautiful in August, when the young burs mingle their even tinge of brown with the fresh green of the glossy leaves. In old age it has the same firmness that is so noticeable in the oak, and seems to be just as regardless of the winds and gales.

The character of the leaf and the manner in which the branches of a tree divide and ramify have so much to do with certain beautiful effects, that I shall make some remarks on these features in two of our maples. The sugar or hard maple is the most useful member of this genus, and may advantageously be compared with the red maple, which is perhaps more beautiful.

It is of great advantage to both of these trees that the sweep of their branches, which is carried out in ample, undulating lines, is in perfect harmony with the elegance of their foliage. In the sugar maple the latter spreads over the boughs in soft and pleasing contours. The leaves are a trifle larger than those of the red maple, and their edges are wavy or flowing, while their surfaces are slightly undulating and have less luster than those of the other tree. They are thus well fitted to receive a flood of light without being in danger of presenting a clotted appearance. The petioles, or little leaf-stems, assume a more horizontal position than they do in the red maple, and the twigs are usually shorter, which allows a denser richness in the foliage, which every breeze plays upon and ruffles as it passes by.

Spray of the Sugar Maple

Spray of the Red Maple

The red maple has a more airy look. This is due partly to the character of the leaf, but primarily to that of the branchwork. The main branches spread out in easy, flowing lines, much as they do in the sugar maple; but they assume an ampler range, and the last divisions, the twigs, take on decided curves, rising to right and left. On these the leaves multiply, each leaf poised lightly upon its curved petiole. As compared with the leaf of its congener, that of the red maple is firmer and a shade lighter, especially underneath. It is also more agile in the wind. The effect of the whole is more that of a shower of foliage than of pillowed masses. The curving lines, the elastic spring of every part, and a kind of freedom among the many leaves, make the red maple one of the cheerfullest of trees.

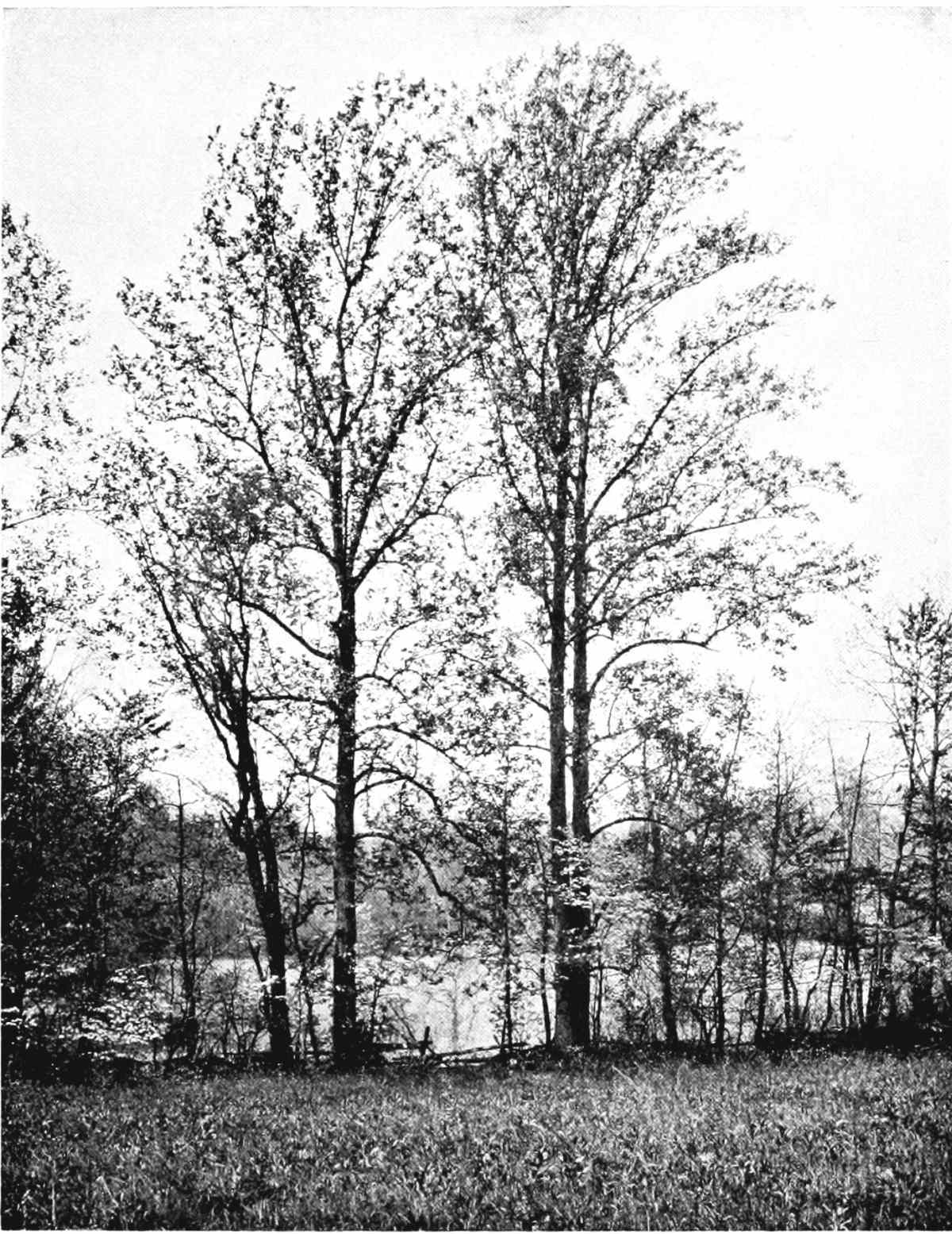

The sugar maple is the larger of the two, and seeks the intervales and uplands, where its size is well set off in the landscape. The red maple, which finds its natural home along riverbanks and in moist places, is interesting at all seasons. When young it is particularly attractive in summer where it fringes lakes and streams. In winter its bright, red twigs present a pleasing contrast to the gray bark or to the snow-covered earth. In the earliest days of spring the little scarlet blossoms break out in tufts that soon ripen into brilliant little keys, looking very pretty where they intermingle with the pale green of the opening leaves.

There is, in fact, more color in the woods in the opening days of spring than is generally admitted or noticed. Many kinds of trees unfold their leaves in some tender shade of rose or golden brown; while others lend a distinct color to a whole section of forest by the opening of their early blossoms.

The maples, however, are chiefly famous for their wonderful richness of color in the fall of the year; particularly the sugar and the red maple, whose brilliancy at this season it would be difficult to match. They exhibit, in truth, a gamut of beautiful tones, from pale yellow to deep orange, and from bright scarlet to vivid crimson. They are among the first to change the color of their leaves, but are quickly followed by other species of trees, whose varying hues blend together and enrich the autumn landscape. The “scarlet” and “red” oaks now justify their names; the flowering dogwood and the sweet gum show their soft depth of purple; the milder tulip tree takes on a golden tint and shimmers in the sun, mingling with ruddy hornbeams, browned beeches, variegated sassafras trees, or the fiery foliage of the tupelos. The swamps are aflame with the brilliancy of red maples, contrasting with the quieter tones of alders and willows.

We may speak of brilliancy and color in our leafy woods at the ebb-tide of the year; but to know their beauty well we must walk among the trees. Nor can pictures tell us all the truth about the tints of autumn. How should we receive from them the atmospheric effects that nature gives, and the indescribable blending and softening that comes from innumerable rays of diffused and reflected light? The beauty also changes from day to day and from hour to hour, for weeks.

Some of the other broadleaf trees deserve to be noticed, though in less detail, as objects of beauty in the forest. The honey locust, one of our largest trees of this class, is distinguished principally for the elegant forms of its branches. The smaller divisions, the twigs, follow a zigzag course which in itself is not beautiful, but the effect is so bound up with the complex spiral evolutions of the larger divisions, the boughs and branches, that the result is only to heighten the elegance of the latter. The foliage of this tree is very delicate, being composed of numerous elliptically shaped leaflets, that are gathered into sprays that hang airily among the bold and sweeping boughs.

Much might be said here in commendation of the sassafras tree, were it economically more important. Its brown, sculptured bark is very attractive, and its yellowish blossoms, that break in early spring, are fragrant. The leaves are of several shades of green, and vary considerably in outline. When in full leaf, the outward form of the tree is striking in appearance, its foliage being massed into rounded and hemispherical shapes that group themselves in the crown of the tree in well-proportioned and tasteful outlines.

The birches, too, are very attractive trees, especially where they have ample room to develop. The white birch appears at its best where it is sprinkled in moderation among open groves of other trees. To the forester it is of some importance, as its seedlings rapidly cover denuded or burnt areas. They also shield from excessive sunlight or from frost the seedlings of more valuable kinds that may have sprouted in their welcome shade; until, gaining strength, the latter after a few years push up their tops between the open foliage of their protecting “nurses.” The white birch may be seen performing this good office in many a fire-scarred piece of woodland throughout the Northeastern States. Often, too, we see it standing a little apart, as at the edge of a forest; its slender branches drooping around the pure white trunk and its agile leaves gleaming as they wave in the light breeze. It is like one of those single notes in music that glide into universal harmony with irresistible charm.

The yellow birch, on the contrary, is most beautiful in the depth of the forest. It is a large, useful tree. In the Adirondacks I have often admired its tall, straight trunk as it rose above the neighboring firs and spruces and unfolded its large, regular crown of dense dark foliage, relieved underneath by the thin, shining, silvery to golden-yellow bark, torn here and there into shreds that curled back upon themselves around the stem.

The white elm, well represented in the avenues of New England, is widely distributed. It is a tree for the meadow, although its natural grace and, one might almost say, inborn gentleness are preserved along the fringes of the forest and on the banks of streams. It needs some room to show the refinement of its closely interwoven spray. Watch its beauty as it sways in the light wind; or look at a grove of elms after a hoar-frost on some early morning in winter, when the leaves are gone and all its outlines are penciled in finest silver.

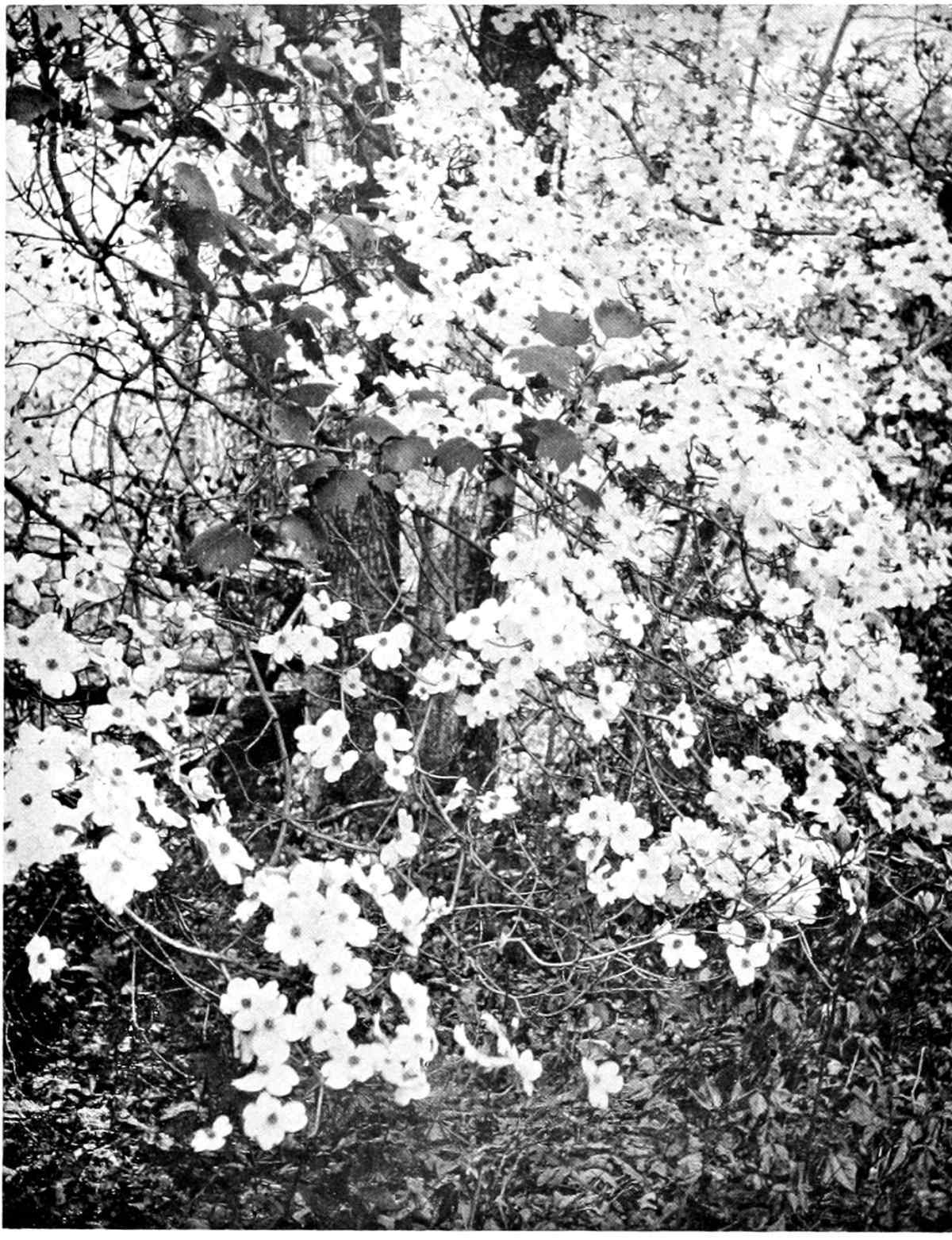

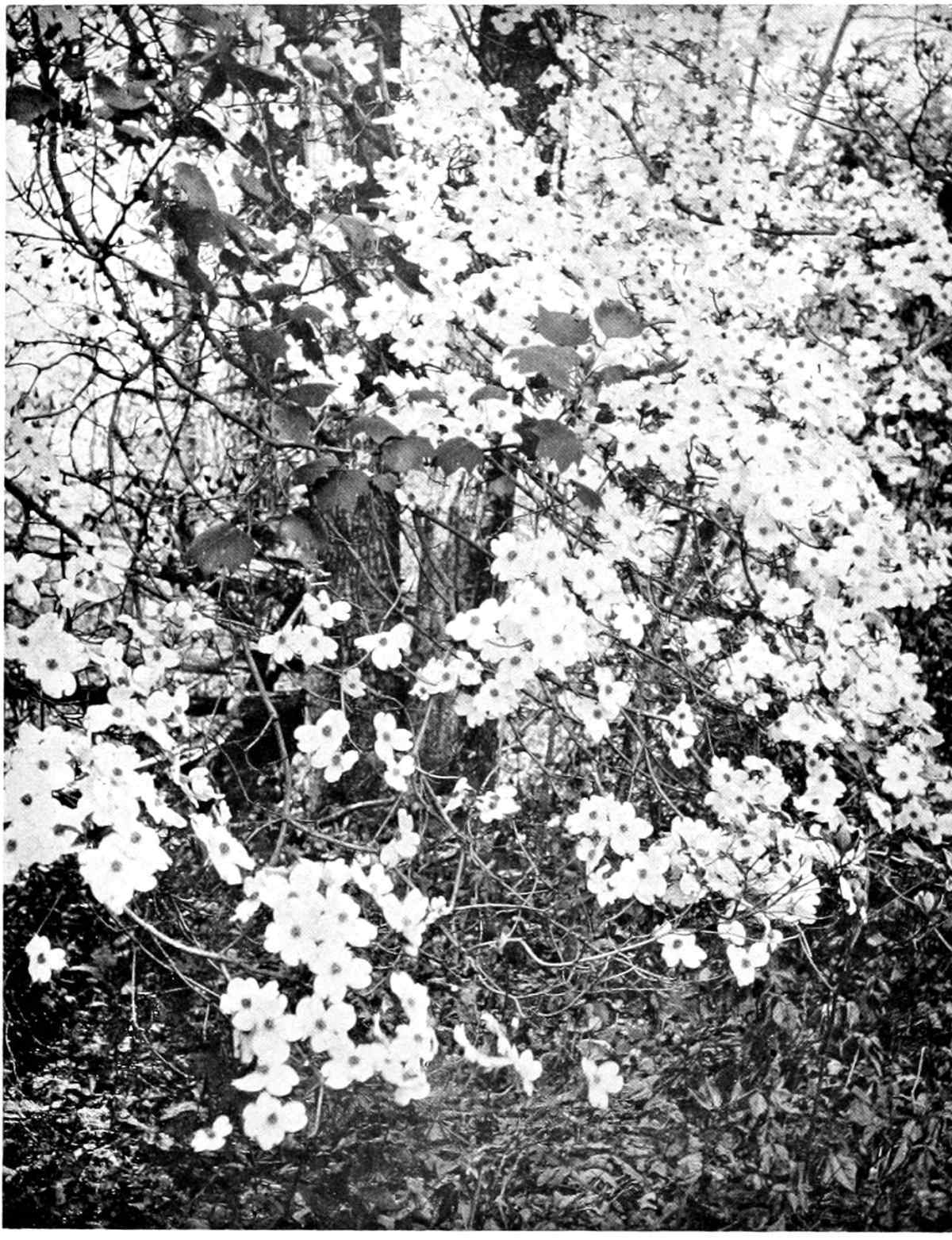

The flowering dogwood is one of our smaller trees, but is exceptionally favored with all manner of beauty. Although it is very common in many of the States, and is not without its special uses, it occupies a subordinate position in the eyes of the forester, being often no more than a mere shrub in form. And yet, while some of the larger trees by their majestic presence lend grandeur to the forest, the dogwood brings to it a charm not easily forgotten. In spring, when it is showered all over with interesting, large, creamy-white flowers, it is an emblem of purity. Its leaves, which appear very soon after the bloom, are elegantly curved in outline, soft of texture, light-green in summer, and of a deep crimson or rich purple-maroon in autumn.[2] In winter the flowers are replaced by bright, red berries. Its spray of twigs and branchlets, formed by a succession of exquisitely proportioned waves and upward curves, is not as conspicuous, though hardly less ornamental at this season than the fruit.

The Dogwood in Bloom

As a shrub, being among the very first to bloom, it decorates the forest borders in spring, or stands conspicuously within the forest. It is found everywhere in the Appalachian region. In the coastal plain it is associated with the longleaf pine, or may be seen among broadleaf trees, or standing among red junipers, as tall as they and quite at home in their company.

Before turning to coniferous trees, the tulip tree deserves some attention on account of its usefulness, its extended habitat, and its beauty as a forest tree. It is closely related to the magnolias, to which belongs the big laurel of the Gulf region, an evergreen species that might be called the queen of all broadleaf trees. But the big laurel must here give place to the tulip tree, because it is not so distinctively a forest tree, and is much more restricted in its geographical distribution.

The first general impression of the tulip tree is, I venture to say, one of strangeness. There is a foreign look about the heavy, truncated leaves, and an oriental luxury in the large, greenish-yellow flowers. These appear in May or June, while the conelike fruit ripens in the fall. When the seeds have scattered, the open cones, upright in position, remain for a long time on the tree, where they are strikingly ornamental.

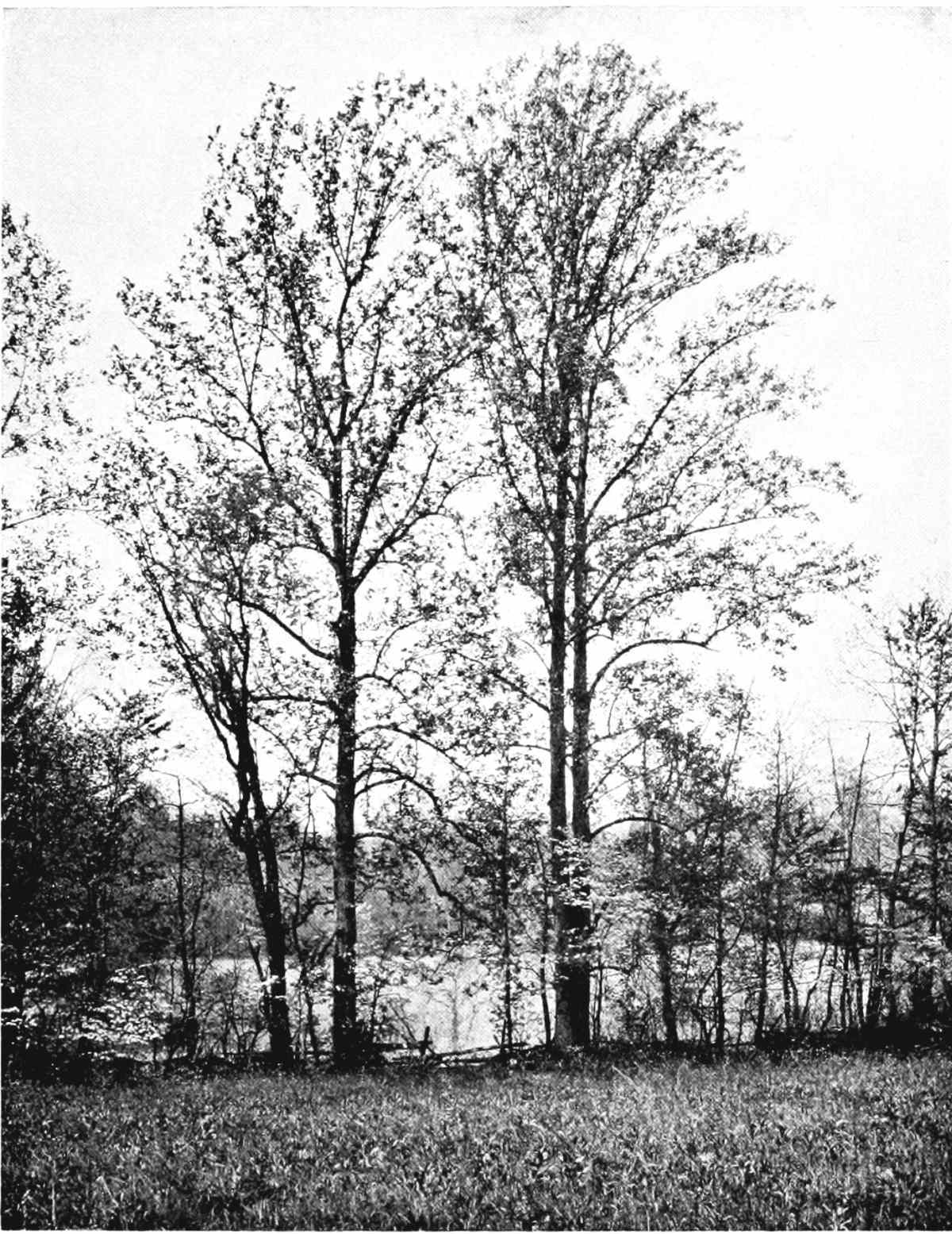

Esthetically the most important feature of the tulip tree is an expression of dignity and stateliness, which gives it a character of its own. Its extraordinary size renders it a conspicuous object in the forest, the more so because we usually find it associated with a variety of other trees of quite different aspect. Michaux, who has told us much about the forest flora of the eastern United States, could find no tree among the deciduous kinds, except the buttonwood, that would bear comparison with it in size, and he calls it “one of the most magnificent vegetables of the temperate zone.” Its columnar trunk continues with unusual straightness and regularity nearly to the summit of the tree. Its limbs and branches divide in harmonious proportions, reaching out as if conscious of their strength, and yet with sufficient gracefulness to lend dignity to the tree. The lower boughs, especially, are inclined to assume an elegant sweep, deflecting sidewise to the earth, and ending with an upward curve and a droop at the outer extremity. Often the crowded environment of the forest does not admit of such ample development; yet even under such conditions the tulip tree preserves much of its elegance and is generally well balanced.

Tulip Trees

When young it does not appear to much advantage, being rather too symmetrical. Nevertheless I have found it described as a tree of “great refinement of expression” at that age. As soon as it begins to put on a richer crown of foliage and to develop a sturdier stem and more elegant lines in the disposition of its branches, it becomes invested with its peculiar aspect of magnificence, increasing in gracefulness and grandeur from year to year. Its bark, at first smooth and gray, gradually becomes chiseled with sharp small cuts; then takes on a corrugated appearance, becomes brown, and finally turns into deeply furrowed ridges in the old tree. Now the foliage, too, seems to clothe the massive boughs more fitly, being denser and in size of leaves more in accordance with the increased dimensions of the tree.

The foliage of the tulip tree is, in truth, one of its principal points of beauty, and is inferior only to the stateliness of its form. The opening leaf-buds are conical, exquisitely modeled, and of the tenderest green. The leaves unfold from them much as do the petals in a flower, but quickly spread apart on the stem. As they grow larger they still preserve their light-green color, but take on a mild gloss. They are ready to shift and tremble on their long leaf-stalks in every breath of wind, which gives them a decided air of cheerfulness. We may see the same thing in the aspen and in some of the poplars. Under the tulip tree, however, the light that descends and spreads out on the ground is far superior. It is softer and purer. We need not look up to appreciate it, but may watch it on the soil, over which it moves in flecks of light and dark.

“The chequer’d earth seems restless as a flood

Brushed by the winds, so sportive is the light

Shot through the boughs; it dances, as they dance,

Shadow and sunshine intermingling quick,

And dark’ning, and enlight’ning (as the leaves

Play wanton) every part.”

THE CONE-BEARERS

The cone-bearing trees are usually provided with needle-shaped or awl-shaped leaves, in contradistinction to the broad and flat ones that belong to the group described in the preceding section of this chapter. Most of them preserve their foliage through the winter, and are commonly recognized by this evergreen habit. They are much more important to the forester than the other class. The conifers grow on the true forest soils. They range along mountain crests or are scattered over dry and semi-arid regions or along the sandy seashore, while the broadleaf species usually require a better soil and a more congenial climate. This circumstance causes many deciduous forests to be cut down, in order that the better land on which they grow may be utilized for agricultural purposes. Moreover, the wood of the conifers is generally more useful, being in several of the species of great economic importance. Lastly, in their habit of denser growth, and from the fact that these trees are ordinarily found in the form of “pure” forests (in contradistinction to those forests in which a number of species grow intermingled), they furnish certain very important conditions for practical and successful forestry.

The common white pine well deserves to stand at the head of all the conifers or evergreens east of the Mississippi. Though it once covered vast areas in more or less “pure” forests it has been largely cut away, and recurring fires have generally prevented its return; but in certain places it could even now be restored by careful treatment. At present the last remnants of these pineries are disappearing swiftly, and before the methods of the forester can be applied to such extensive areas, this valuable heritage will probably have vanished. Heretofore it has been to us Americans in the supply of wood what bread and water are in daily life. It has been hardly less valued by other nations, having been planted as a forest tree in Germany a full century ago.

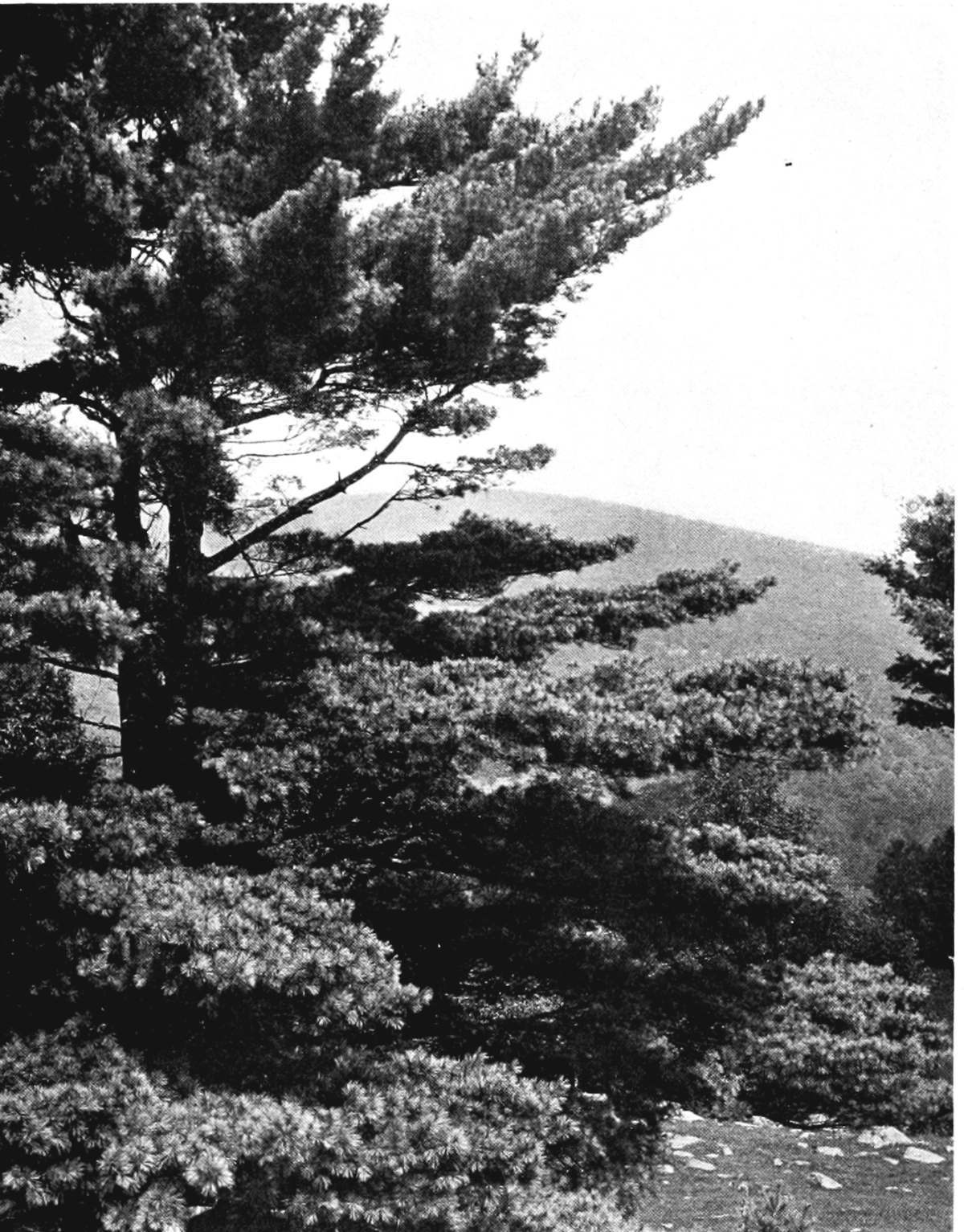

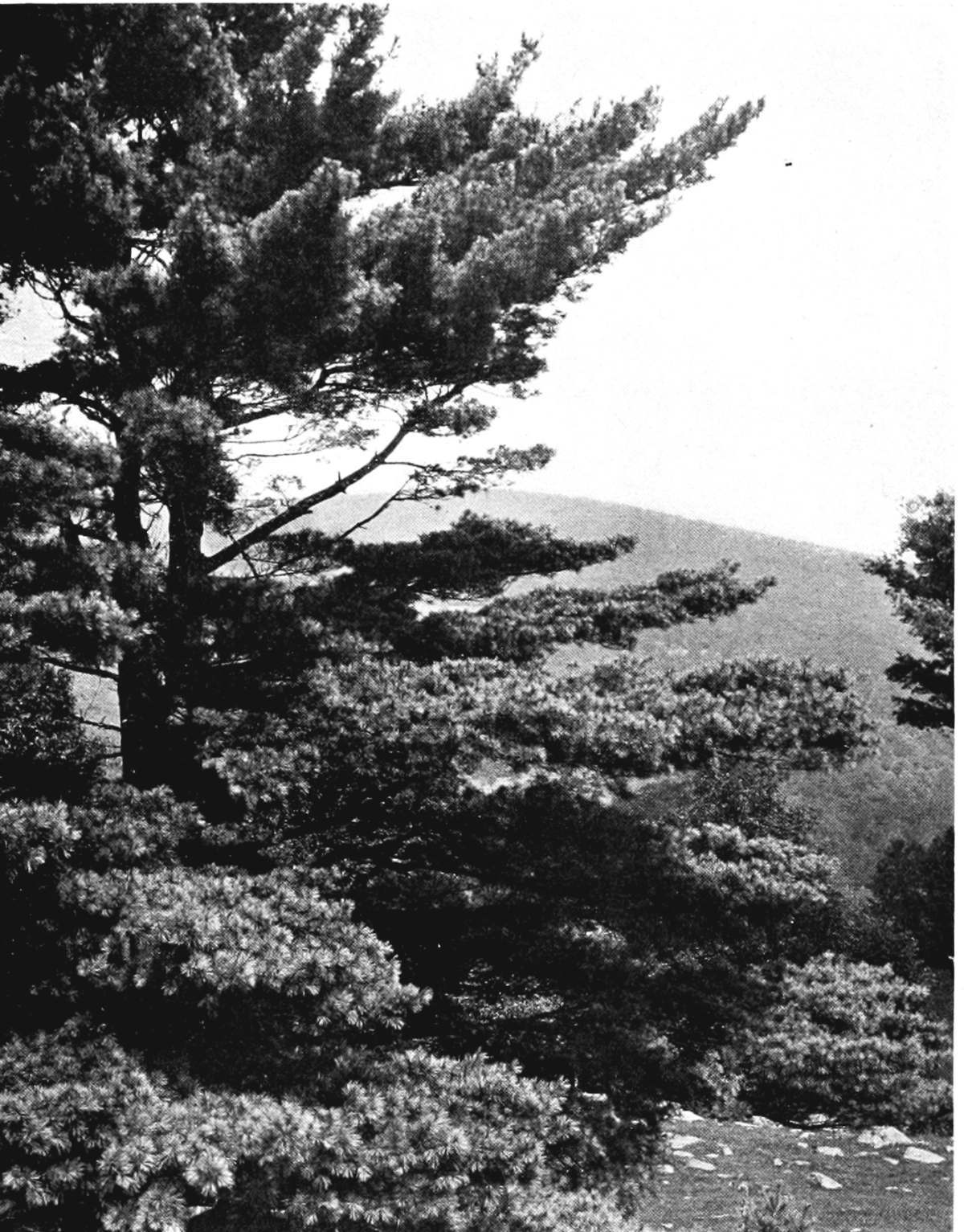

I cannot say what I admire most in the white pine; whether it be the luxuriance and purity of its foliage, or the very graceful spread of its boughs. There is hardly a tree that can equal it for softness and rich color. The tufts of needlelike leaves densely cover the upper surfaces of the spreading branches, and are of a mild, uniformly pure olive-green. Seen from beneath they appear tangled in the beautifully interwoven twigs and stems. It is here that we first begin to notice the exquisite manner of the white pine. The boughs reach out horizontally, with here and there one that ascends or turns aside to assume a position exceptionally graceful and to fill out a space that seems specially to have been vacated for it. I speak of the white pine at the age preceding maturity, when it is in its full strength, but before it has attained the picturesqueness of old age. Following an easy curve, the branch divides at right and left into dozens of finer branchlets, all extending forward and straining, as it were, to reach the light; and these in turn lift up hundreds of twigs and little stems to enrich the upper surfaces with bushy tufts of lithe green needles. The elegance of this habit in the white pine appears to advantage when we stand a little above it on a gentle slope and see the branches clearly defined against the surface of a lake below or some far-away gray cloud.

Both in middle age and when it is old the white pine is a distinguished-looking tree. When young it is sometimes elegantly symmetrical; but more often, owing to a crowded position, it lacks the air of neatness that belongs to a few of the other pines and to most of the firs. At maturity it is a very impressive tree, especially in the dense forest, where it develops a tall, dark, stately stem. In its declining years the branches begin to break and fall away, no longer able to bear the weight of heavy snows. This is often the time when it is most picturesque.

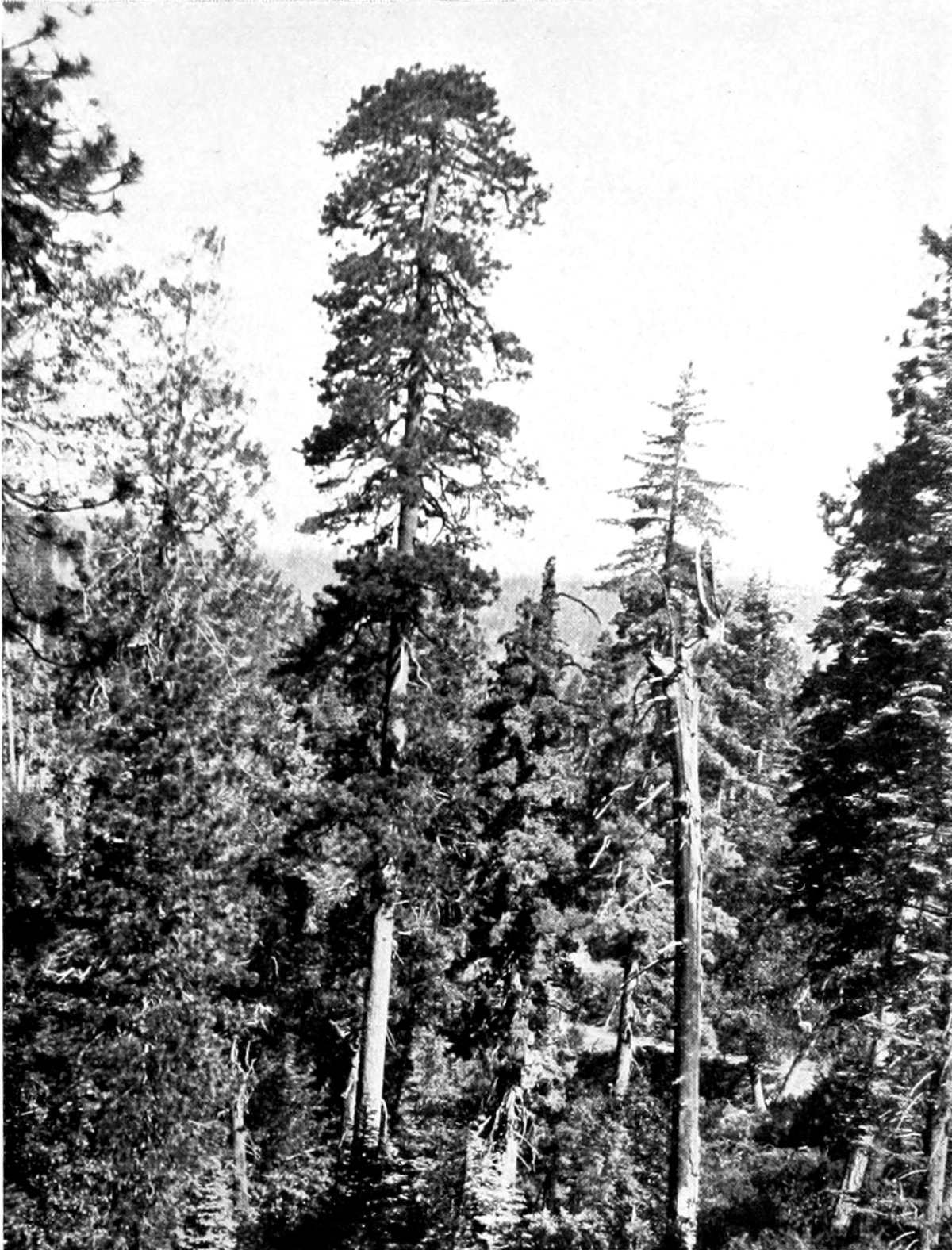

Character of the White Pine.

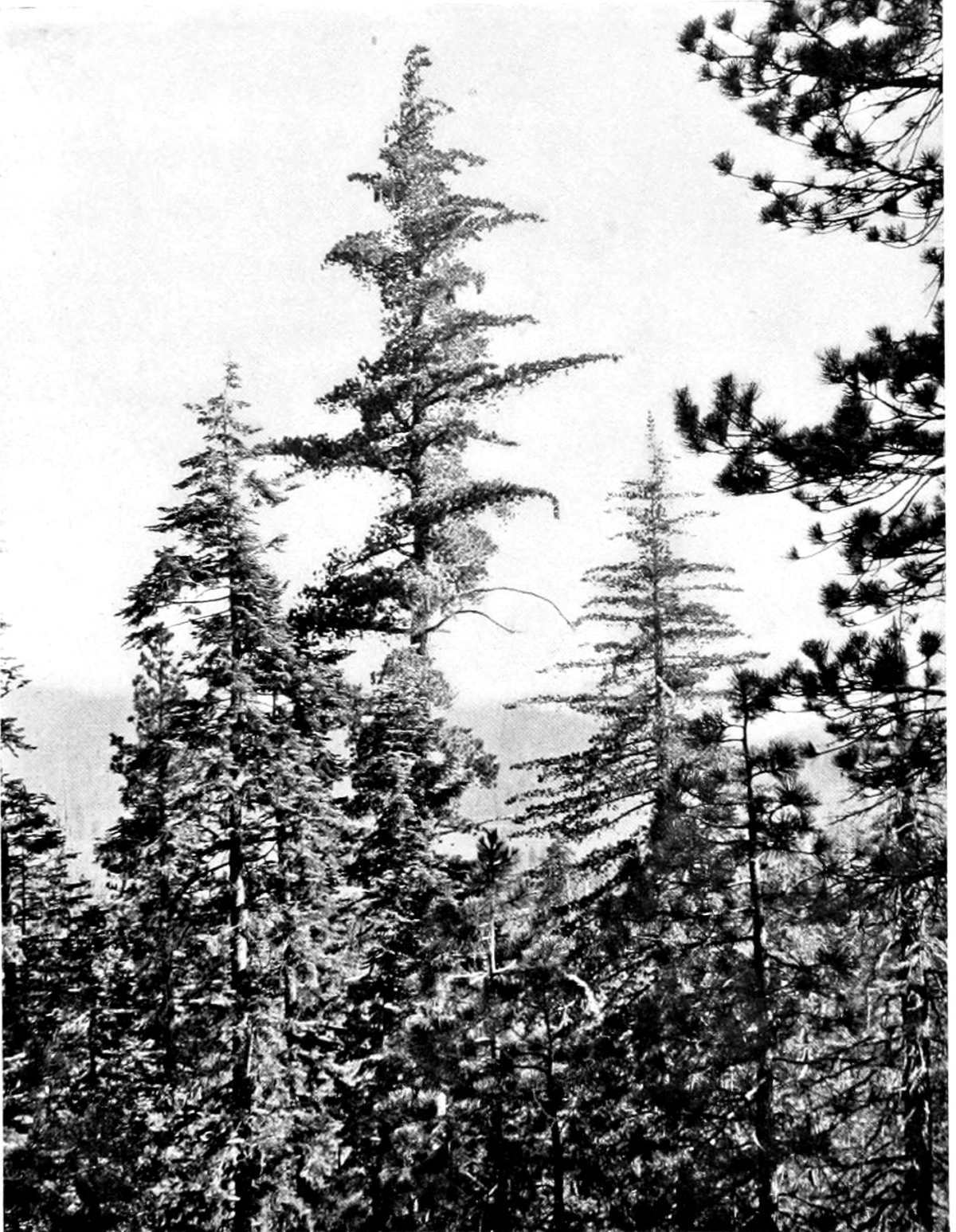

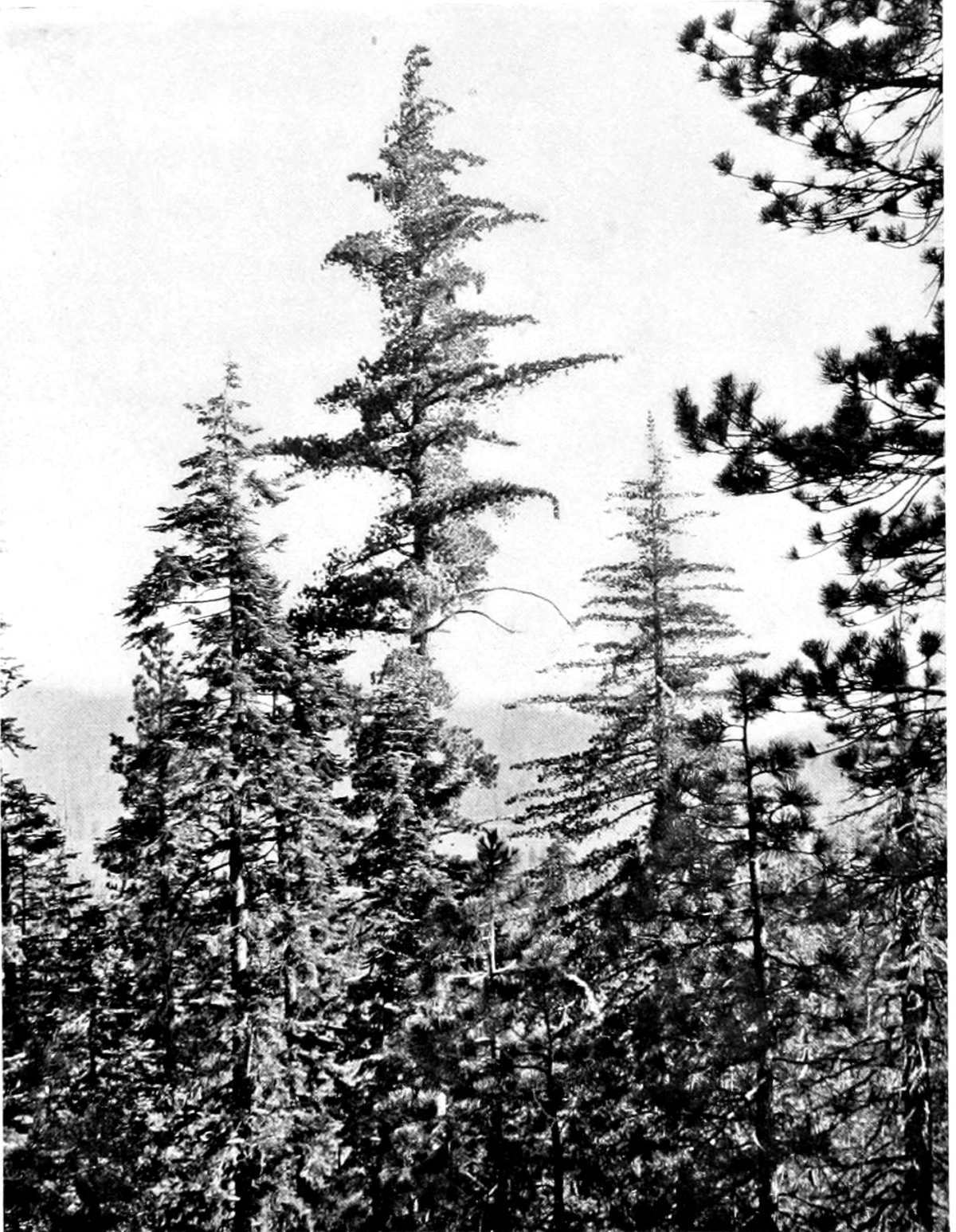

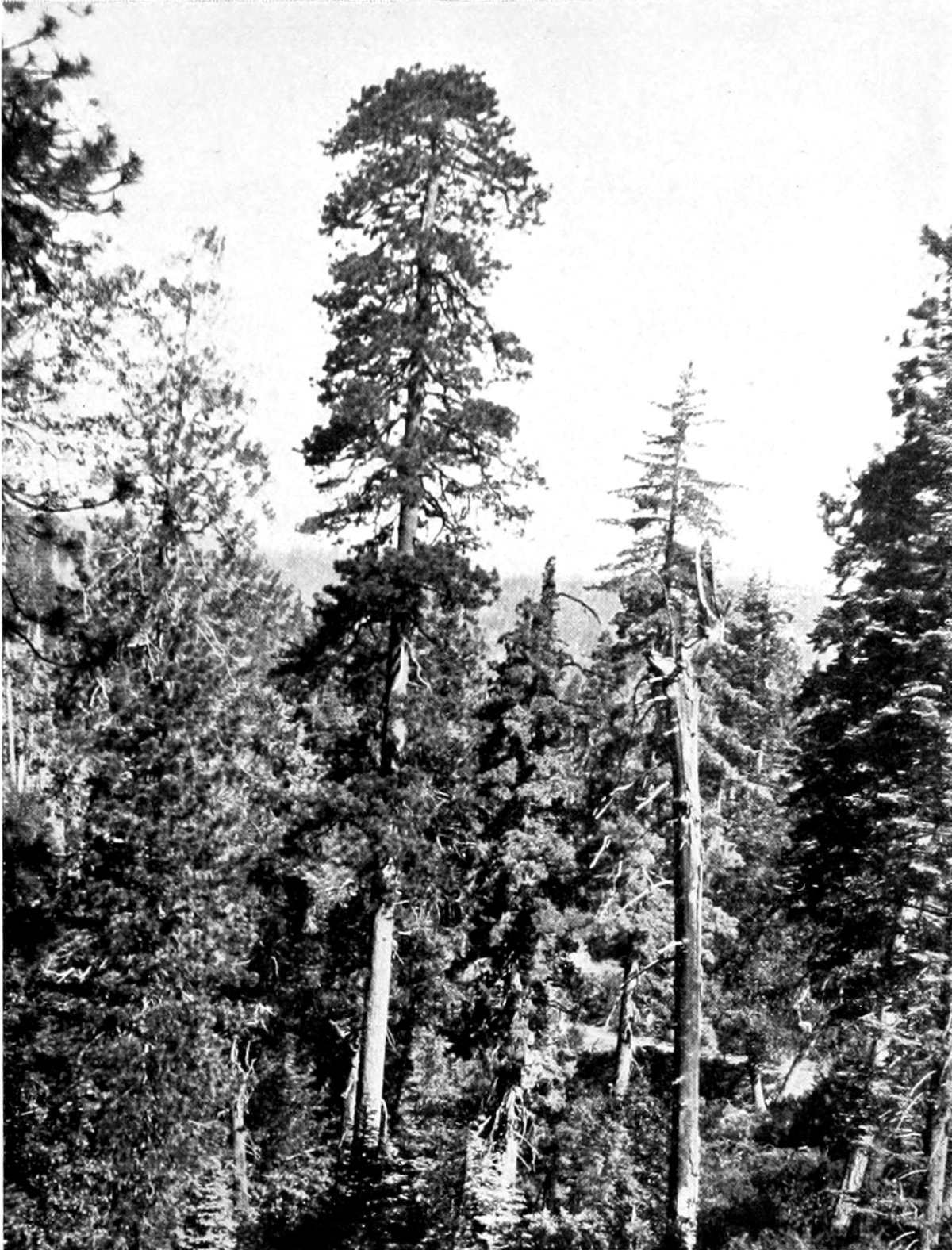

The representatives of the white pine in the West are the silver pine and the sugar pine. Though both may be easily recognized as near relatives of the eastern species, either by the typical form of the cones or by the plan and structure of the foliage, each of the western trees possesses a majesty and beauty of its own. The silver pine is more compact in its branches than the white pine, and has somewhat denser and more rigid foliage. Its dark aspect is well suited to the mountains and ridges of the Northwest, where it commonly abounds. The sugar pine, which is the tallest of all pines, impresses us by its picturesque individuality. Its great perpendicular trunk not infrequently rises, clear of limbs, to the height of a hundred and fifty feet, and is surmounted by an open pyramidal crown of half that length, composed of long and slender branches that are full of motion. While the texture of the foliage is not as delicate as in the white pine, it is smooth and elastic, and has an even bluish tinge that shows to great advantage when the needles are stirred by the wind. Its cones, which are of enormous size, hang in clusters from the extremities of the distant boughs, which droop beneath the unusual weight. Two of these cones, which I have lying before me, measure each nineteen inches in length. Well might Douglas, the botanist who named this tree, call it “the most princely of the genus.”

Sugar Pines

Young Bull Pines in the foreground at the right and an Incense Cedar at the left.

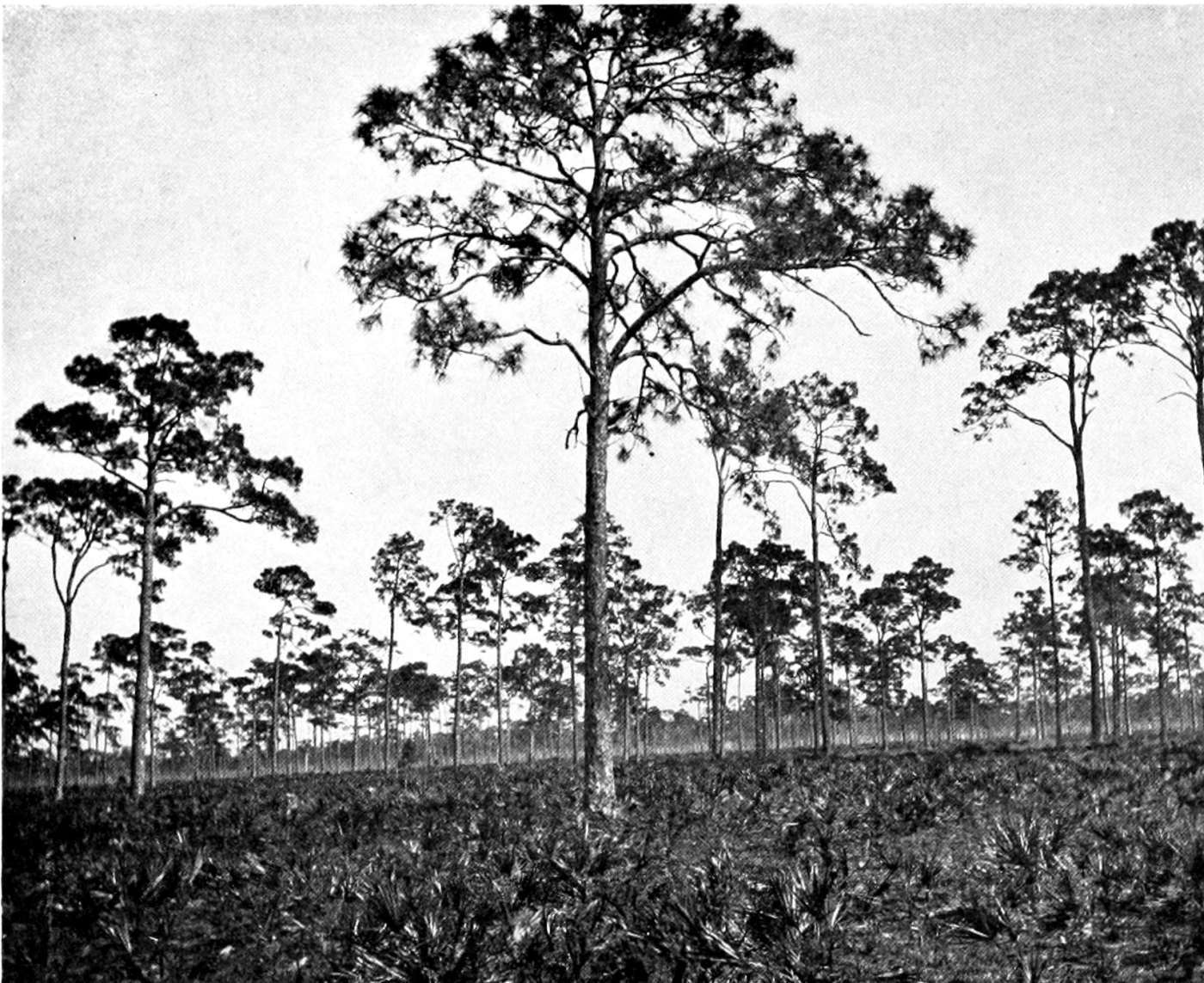

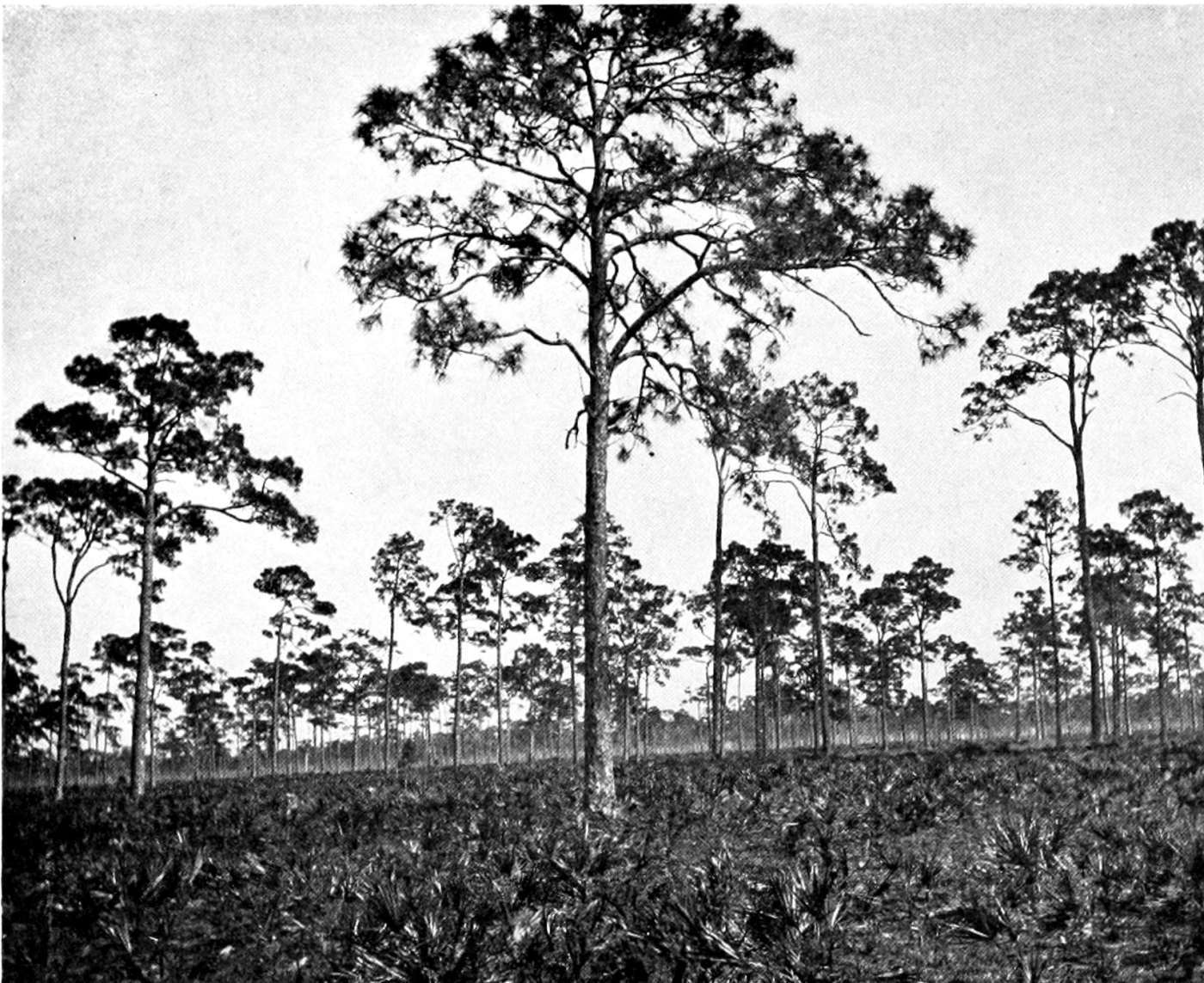

The longleaf pines of the Southern States should be noticed for their picturesqueness. The Cuban pine is restricted to isolated tracts in the region of the Gulf and eastern Georgia. The loblolly pine and the longleaf pine, near relatives of the Cuban pine, cover extensive tracts in low, level regions of the Southern States, and are most interesting in old age. Standing, it may be, on a sandy plain not far from the sea, among straggling palmettos, they lift their ample crowns well up on their tall, straight stems, and contort their branches into surprising forms; so that, looking through their crowns at a distance in the dry, hazy air of the South, with possibly a red sunset sky for a background, they are extremely fantastic and entertaining.

There are two other pines that have a similar tortuous habit in the growth of their branches: the pitch pine of our eastern coast States and the lodgepole pine of the Rocky Mountains. These, however, have an esthetic value for quite a different reason. In the case of the pitch pine it is due to a natural peculiarity otherwise rare among conifers; for, this tree has the power of sprouting afresh from the stump that has been left after cutting or forest fires, thus healing in time the raggedness and devastation resulting from necessity, neglect, or indifference. The lodgepole pine of the West performs the same patient work over burned areas through the remarkable power of germination belonging to its seeds, even after being scorched by fire. Thus both of these trees not only furnish useful material, but restore health and calmness to the forest.

Courtesy of the Bureau of Forestry

A Pinery in the South

In connection with the longleaf pines of the Southern States, the bull pine of the West deserves to be noticed on account of its near botanical relationship and the somewhat similar economic position which it occupies. It is the most widely distributed of western trees, being found in almost every kind of soil and climate along the Pacific coast and throughout the Rockies. Over so wide a range, growing under very different conditions of soil, temperature, light, and moisture, it varies greatly in form and appearance. We encounter it on dry, sterile slopes or elevated plateaux in the interior, and walk for miles through the monotony of these dark bull pine forests, in which the trees are of small stature and seem to be struggling for their life. Again we meet it on the humid western slopes of the Sierra Nevada, associated with the sugar pine and other lofty trees. Here we scarcely recognize it. It holds its own among the company of giants, and is full of vitality, freedom, and strength; with brighter, redder bark and stout, sinuous branches; with longer needles and larger cones. The sunlight fills its ample crown spaces, and the wind murmurs in the foliage overhead; for the pines are the master musicians of the woods.

The Bull Pine in its California Home

The Southern States and the Gulf region furnish us with a conifer of striking originality and great usefulness. This is the bald cypress, which may have caught the reader’s eye in some northern park by the elegant forms of its spirelike growth. It rises high and erect, a narrow pyramid clothed in the lightest green foliage. The latter is composed of delicate feathers of little elliptical leaves that hang drooping among the finely interwoven short branches. This is in its cultivated northern home, w