II

FOREST ADORNMENT

THOUGH there can be no forest without trees, it may be asserted with equal truth that trees alone would make but an incomplete forest.[5] Under the old trees we find the young saplings that are in future years to replace them and in their turn are to form a new canopy of shade. In their company is a vast variety of shrubs, ferns, and delicate grasses and flowers that decorate the forest floor. Vines and creepers gather about the old trees and clamber up their furrowed trunks. In autumn the ground is strewed with fallen leaves, motionless or hurrying along before the wind. These gather into deep beds, soft to the tread, and at last molder away in the moist, rich earth. In the needle-bearing forests of the mountains brilliant green mosses replace the shrubs and flowers and deck the bare brown earth.

There are lifeless sources of beauty in the woods, too, that are not easy to pass by unnoticed: rocks with interesting forms and surfaces; forms that are lifeless, yet take on distinct expression by their different modes of cleavage, and surfaces that drape themselves in the choicest paraphernalia of drooping moss and rare lichen; prattling mountain streams; cascades; and glassy pools. These are “inanimate” things with a kind of life in them, after all.

Courtesy of the Bureau of Forestry

A Passageway through Granite Rocks

Lastly, there are the true owners of the forest: the bird that hovers round its borders; the free, chattering squirrel; the casual butterfly that leads us to the flowers; and the large game that inhabits the hidden recesses and adds an element of wildness and strange attraction to these quiet haunts.

All this wealth of detail gives life to the forest. The shrubs, above the rest, should here interest us somewhat more minutely. They are often the most conspicuous objects in the embellishment of the forest; and since our investigation was to be guided to some extent by considerations of usefulness, it ought to be added that shrubs not infrequently exercise a beneficial influence on the vigor and well-being of the trees themselves. Trees, shrubs, and certain of the smaller plants—so long as their root systems are not too dense and intricate—are of value on account of their ameliorative effects on temperature and moisture. This is more important in this country, so extreme in its climatic variations, than in northern Europe. In the dry and parching days of summer the shrubbery of the woods, by its shade, helps to keep the earth cool and moist. This mantle of the earth, moreover, conducts the rain more gradually to the soil, exercising an efficient economy. In the fall and winter the shrubs, which are densest near the forest border, help to break the force of the sweeping winds which might otherwise carry away the fallen leaves, so useful in their turn because they are conservators and regulators of moisture and contain valuable chemical constituents which they return to the soil.

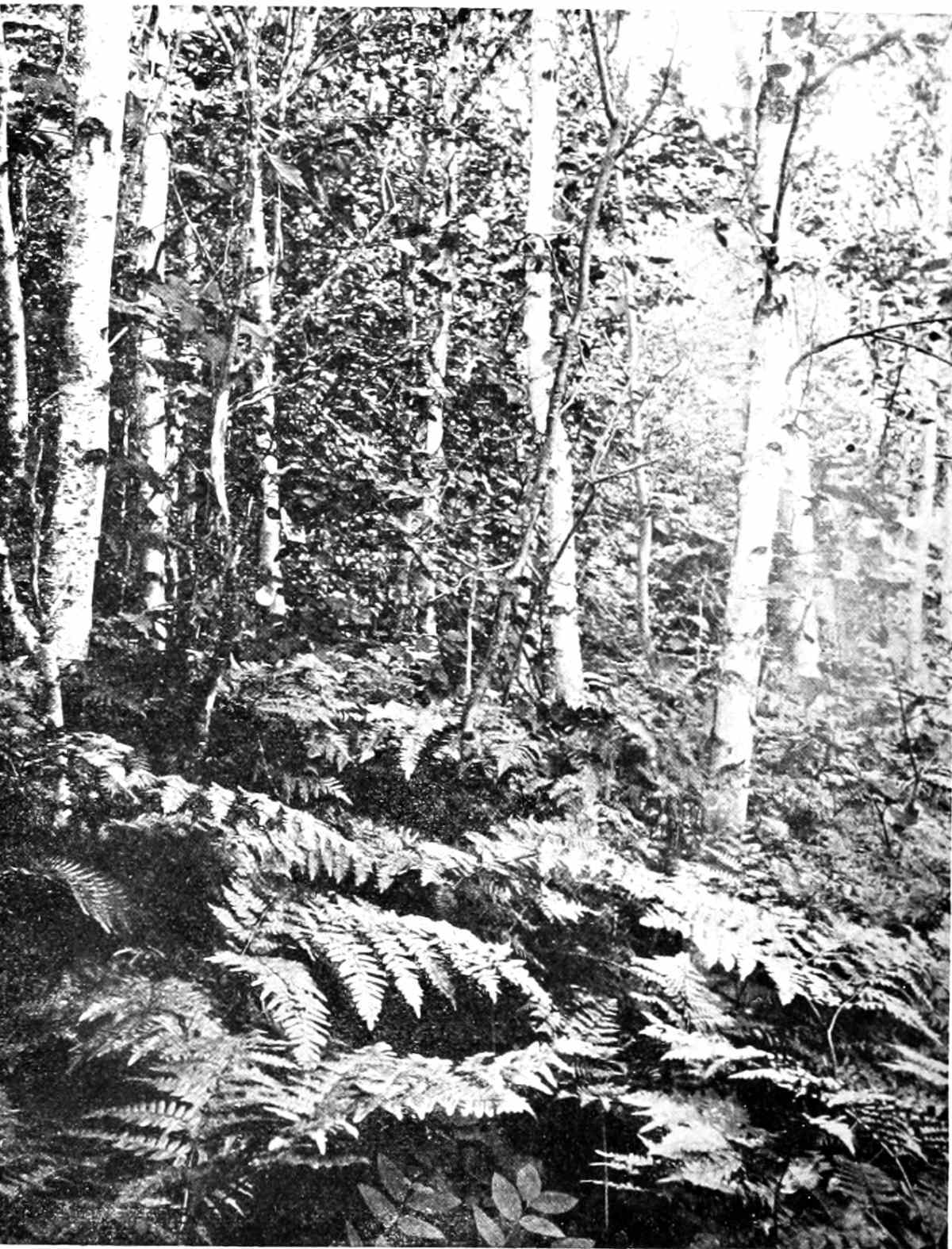

Courtesy of the Bureau of Forestry

Shrubbery and River Birches. New Jersey

The pine barrens of New Jersey illustrate these principles. In close proximity to the sea a welcome moisture enters the forest with the ocean breezes. Penetrating farther inland, it is not so entirely dissipated as to preclude a varied undergrowth of shrubbery, which in turn renders a welcome aid to the forest by the protection it affords to the porous, sandy soil, which would soon dry out under the scant shelter of the pervious pines. Underneath these the kalmia or calico bush, with its large and showy bunches of flowers, is abundant. In late summer the sweet pepperbush is there, laden with its fragrant racemes; in winter, the cheerful evergreen holly of glossy green leaf and bright berry. In the dry and sunny places we find the wild rose, the trailing blackberry, with its rich color traceries on the autumn leaves, and the no less brilliant leaves of the wild strawberries underfoot. We come upon the creeping wintergreen and the local “flowering moss.” The fragrant “trailing arbutus,” here as elsewhere, is an earnest of the generous returning spring. Along the creeks and brooks are masses of honeysuckles, alder bushes, and sweet magnolias.

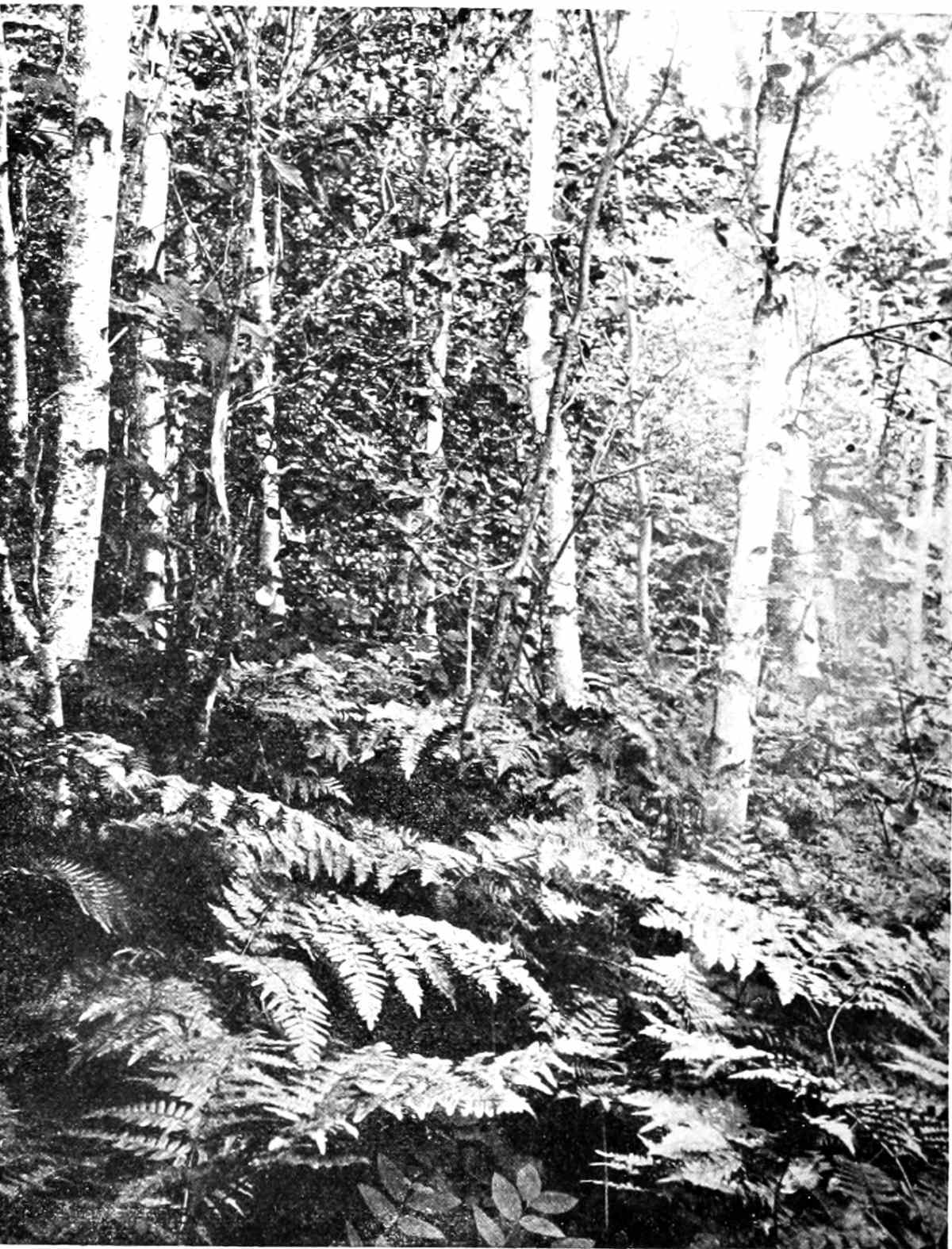

Fern Patch in a Grove of White Birch

The coniferous forests of the Rocky Mountain region are either too dry or too elevated to promote a luxuriant undergrowth; but we find it in the humid coast region of Oregon and Washington, within the forests of fir, pine, and spruce. In the deciduous forests, however, the shrubbery attains its best development, for its presence depends largely upon moisture, climate, and soil, and these conditions are usually most favorable in our broadleaf districts. In the latter, moreover, the shrubbery exercises its influence most efficiently, for many of the pines will bear a considerable amount of heat and drought, and several other conifers show their independence and a different kind of hardihood at high and humid elevations. The varied and beautiful forms of undergrowth in our broadleaf forests—the shrubs, the vines and graceful large ferns, and the smaller plants that live along the forest borders and penetrate within—may be regarded as one of the distinctive features of American forest scenery.

In such forests, and along their borders, the birds like to make their home. Among the bushy thickets they find a secure shelter, and some of them seek their food among the fruits and berries that grow there. They all possess their individual charms, and infuse such varied elements of life and cheer into the woods that even the most commonplace scenes are transmuted by their presence, while those that were already beautiful receive an added attraction. In winter there is nothing more harmonious than a flock of snowbirds flying over frosted evergreens toward some soft gray mist or cloud. For grace and ease of movement I have never seen anything more airy than the Canada jay alighting on some near bough, softly as a snowflake, to watch and wait for the scraps of the forester’s meal. Another interesting bird to watch in his movements is the red-winged blackbird. Out along the edges of the forest and in the swamps and marshes lying between bits of woodland, he may be seen from earliest spring to the last days of fall.[6] We cannot help watching him passing restlessly to and fro by himself, or circling happily about in the flock, returning at last to his clumps of alders and willows, or disappearing among the hazy reeds and grasses. But if, instead of grace and movement, we are more interested in sound, we shall find no songbird with sweeter notes than the thrush. Whatever added name he may bear, we are sure of a fine quality of music; music with modulating notes, plaintive and clear, that drive away all harshness of thought.

Let us again consider the undergrowth in the forest. Where shrubs and tender growths abound the wintry season cannot be desolate or dreary. When the display of summer is over they attract the eye by their bright fruits and their habits of growth. Their branchlets are often strikingly pretty in color and well set off against the snow. Their intricate traceries of twig and stem are an interesting study. The copses of brown hazels that spread along the mountain side and the dusky alders or yellow-tinted willows are in perfect harmony with this season of the year.

It is by crowding into masses that our shrubs of brighter blossom produce some of the most superb effects of spring. A multitude of rhododendrons or great laurels covers some mountain side, carrying its drifts of pale rose far back into the woods. A mass of redbuds and flowering dogwoods, the former again rose-colored, the latter a creamy white, pours out from the forest’s edge among ledges of rock and low hills. The wild plums and thorns, with their delicate flowers, are beautiful in the same manner, and in addition have a pretty habit of straying out and away from the woods, much like the red juniper.

Our shrubs are no less beautiful in their separate parts than they are magnificent in their united profusion. The common sweet magnolia is especially well favored. Its elegantly elliptical leaf, with smooth surfaces, glossy and dark green above, silken and silvery below, is one of the most attractive to be found. Its flower cannot help being beautiful, for beauty is the heritage of all the magnolias. Often, however, half the pure ivory cups lie hidden in the leaves, to surprise us on a closer approach with their beauty and sweet fragrance. Altogether this favored shrub is one of the most exquisite objects of decoration, whether in the swamp, along brooksides, or through the damp places of the forest.

The hawthorns, which, like the sweet magnolia, occur both as trees and as shrubs, combine varied forms of attractiveness, such as compound flowers of white or pinkish hue; sharply edged, elegantly pointed leaves; bright berries; and closely interwoven branchlets stuck about with thorns. The redbud, which I have already mentioned, holds its little bunches of flowers so lightly that they look as if they had been carried there by the wind and had caught along the twigs and branches. Very different from these, yet no less interesting in its way, is the staghorn sumach, which is of erratic growth and bears stately pyramids of velvety flowers of a dark crimson-maroon. There is a fine contrast, too, where the serviceberry, with early delicate white blossoms, blooms among the evergreens and the opening leaves of spring.

Another word about the West. The undergrowth of the northerly portion of the Pacific coast region has already been referred to; but there extends throughout the Southwest, penetrating also northward and eastward, another kind of forest growth that is so distinct in character from all others that it should be specially described. It is, in fact, quite opposite in its nature to the shrubbery of the more humid forest regions in that it shows a tendency to seek the arid, open, sunny slopes, where it forms a scrubby, though interesting, and varied cover to the rough granite boulders and loose, gravelly soils. This growth is everywhere conveniently known as “chaparral,” whether it be the low, even-colored brush on the higher mountains or the dense, scraggy, promiscuous, and impenetrable thicket of the foothills and lower and gentler slopes.

The impression which the chaparral makes depends largely upon the distance at which it is viewed. If we stand in the midst of a dense patch of it we see of how many elements it is composed; how the shrubs of different size, shape, and character crowd each other into a tangle of branches, some not reaching above the waist, others closing in overhead. The ceanothus, with its dull, dark-green foliage and bunches of small white flowers, which appear in June, stands beside the stout-stemmed, knotty, twisted manzanita, with its strikingly reddish-brown bark and sticky, orbicular, olive-colored leaves. Among smaller shrubs we find the aromatic sage brush, of a light-gray, soft appearance, and the richer, darker, small-leaved grease-wood, or chemisal, as it is more commonly called farther north, with its small, white-petaled flowers enclosing a greenish-yellow center. Very plentifully scattered among all these we usually find the scrubby forms of the canyon live oak and the California black oak. Here and there we may see a large golden-flowered mallow, or the queenly yucca raising its fine pyramid of cream-colored flowers out of the dense mass.

The far view is quite different. Distance smoothes the surface and somewhat obliterates the colors, though we may still distinguish a variegated appearance. The eye takes in the larger outlines and the scattered pines that sometimes occur within the chaparral. Nor is the latter, as we now perceive, always a dense growth, but may be separated here and there. Indeed, it is often most interesting when interrupted by large granite boulders and jumbles of rocks, with the clean gray shade of which it forms a fine contrast on a clear morning.

A Yucca in the Chaparral

If we look still farther up toward some higher slopes, miles away, we shall see only a uniform and continuous stretch of low brush that appears at that great distance hardly otherwise than a green pasture clothing the barren mountain. As we walk toward it the bluish-green changes to a bronze-green, and then suddenly we recognize the broad sweep of chemisal, with a few scattered scrubby oaks and mountain mahogany in between.

In the account of forest embellishment should be included those humblest plants, the liverworts and mosses and the lichens that so beautifully stain the rocks and color the stems of trees. A close study of all their delicate and tender characters, both of form and color, is always a revelation. Among these lowlier plants it is no uncommon sight in the depth of winter to see a field of fern sending a thousand elegant sprays through the light snow-covering; or half a dozen kinds of mosses, all of different green, but every one pure and brilliant, gleaming in the shadow of some dripping rock. Between the rock and its ice cap, covered by the latter but not concealed from view, there is a fine collection of the most delicate little liverworts and grasses, herbs with tender leaves, and even flowers, it may be, on some earthy speck where the sun has melted the ice—all as if held in cold crystal.

A word also remains to be said about the vines and creepers. As far north as Pennsylvania, and even to the States bordering the Great Lakes, these clambering plants are a conspicuous element in the forest. Virginia creeper, clematis, the hairy-looking poison oak, and the wild grape, are among those that are most familiar. In the woods of the lower Mississippi Valley the wild grapevines often make a strange tangle among the old and twisted trees and hang in long festoons from the boughs. They are not uncommon in some of the northerly States, though less rank and exuberant in growth.

The common ivy is one of the most beautiful of all creepers. It makes a fine setting for the little wood flowers that peep from its leaves. I like it best, however, where it clings to some old oak or other tree and brings out the contrast between its own passiveness and weakness and the strength of the column that gives it support.