CHAPTER IV

Bears

THE day following the dance all the villagers felt very tired; they slept late, neglected to go hunting, and spent the time standing about talking with the strangers, or escorting Omialik from house to house; showing him their family belongings and clothes, their lamps and pots, hunting implements, bows and arrows, spears and harpoons. He wanted to take a number of these away with him to be placed in museums in New York and other cities (where many of them are now, and where you can go and see them if you care to) and the business of trading took a long time. Moreover he asked a variety of questions about where they got the stone for their lamps and the wood for their sleds, what sort of people lived to the eastward, and so on and so forth. All their answers he wrote down in a small book.

Although the Eskimos think it impolite to ask questions, they were very kind about answering.

Now this sort of thing, while it was important to the white man, promised a dreadfully dull day for two lively lads like Kak and Akpek. So when they had hung around several hours waiting for action and excitement they gave up, thoroughly disgusted, and decided to have some fun of their own.

“Let’s go out to the rough ice and play at climbing houses six times six rooms high,” Kak suggested.

If you stop to consider you will see this notion of climbing the outside of a tall house was perfectly natural to an Arctic boy. Kak had no conception of buildings with straight walls, for his winter home was shaped like an old-fashioned beehive, and the proudest summer home they ever attained was a tent. Besides he had never in his life seen a stairway, and it is extremely difficult to imagine what you have never seen. How could he think of climbing up inside a house by means of stairs? But he had often scrambled on top of their snow dome to slide down with the girls, or get a view of the surrounding country; and so when he told Akpek of houses six times six rooms high, he had in mind a huge pile of snow up the outside of which they would have to walk; and the pressure ice, piled by the winter storms into ridges of great blocks, chunk on chunk, was not such a poor imitation of this idea.

Akpek was eager enough to go. That day he was glad to join in any game suggested by his wonderful cousin; for Taptuna had not been able to resist bragging about his son’s hunting, and the story of the ugrug sounded quite different and terribly impressive when told among the grown-ups. Hearing his father congratulate Kak, and his mother praise him, made the other boy feel pretty small and mean about his boasting of bear hunting the night before; and now he shyly endeavored to make up to his chum for having doubted him.

The boys started off shouting and running races, each anxious to get to the rough ice first and claim the highest hummock for his house. This was a dandy new play and a dandy place to play it. American boys would doubtless have called the game “Castles” for the shining pinnacles and spires of the ice blocks made splendid towers, and the whole mass looked so handsome shimmering in bright sunshine under a cloudless sky, its arms uplifted into the blue, and twinkling all over with a sort of frosted Christmas card effect, it really deserved a magnificent name. But Kak and Akpek had never heard of castles, nor indeed any building finer than the dance hall of the day before, so they were quite content to talk about playing at “high houses.”

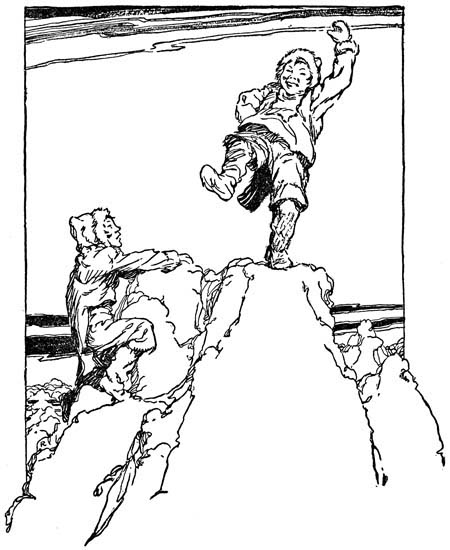

Bursts of speed and rollicking noise both stopped when they struck the rough ice and needed their breath for climbing. From there they went as quietly as hunters, till they had each crested the top of a large cake; then rivalry broke loose.

“I’m above you! Mine is the highest!” Kak cried exultantly, swinging his sealskin boots over the edge of a precipice. But even while he chortled in his glory, Akpek spied a higher peak, and swarming down from his first choice without a word of warning, shinned up the second.

“Yo-ho, there!” he crowed from what was really a daring, difficult perch. “Who said you were on a high house? Look at me!”

“Foxes!” yelled Kak, all his pride gone in a minute. “Come down out of that. Don’t you know I’ve got to be on top because it’s my game!”

But Akpek only jeered.

Then our hero started up furiously to pull his cousin down; and Akpek came laughing, for he was always good-natured, and although a tall lad and a good climber, not at all sorry to be off that slippery ice arm.

“Leave it alone,” he advised. “It’s a beggar!”

“You believe I can climb it?” Kak asked.

“Sure as life,” replied the other, feeling rather sheepish, for this was a thrust at his behavior last night. “’Tain’t hard,” he added.

“All right. So long as you don’t think I’m scared to try,” Kak answered grandly.

“I’M THE KING OF THE CASTLE!”

So they called a truce and abandoned that ice pile for a more tempting, bigger one lying farther out in the ridge. Of course they had to race for it, and Kak, who felt he had been worsted on the last, ran swiftly and climbed like a mountain goat up a wonderful tower which was cut off flat on the top so he could stand erect, and even dance a step or two and wave his arms. And when Akpek came in sight he was dancing up there, singing something like: “I’m the king of the castle!”

Akpek laughed at him, calling, “Hold on, I’m coming too,” and began to climb with all his might.

Kak refused to have company at first, pretending to be very angry, and trying to shove him off. But the other boy said that was no kind of game; he only liked sports where people could be jolly and friendly, that dancing together was far nicer than fighting—think what a fine time they had all enjoyed yesterday instead of rowing and killing each other; so then Kak changed and helped him up, and they joined hands and danced a silent sort of clog-dance out there on top of the towering ice cake.

Now while the boys were away on the ice the Kabluna grew tired of looking at things and talking, and decided to go out alone for a walk with his camera and his gun. He wanted to be prepared for anything, either a good view or a wild animal—particularly the latter. For although the Eskimos were very kind and generous and ready to entertain these guests, feeding them and their dogs as long as the food lasted, Omialik did not care to be dependent on the village. It is always a good thing to hold up your own end in any situation. He knew the people would respect him a great deal more if he were able to give them some fresh meat, instead of having to take part of their supply. He started across the ridge hoping to find a fat seal; and when he reached a good crest sat down, took out his fieldglasses, and commenced to search very carefully in every direction. He did not intend to kill the seal with a spear as the Eskimos do, but hoped to be able to shoot one which had crawled out on the ice to bask in the sunshine. Seals are fond of coming up and lying about snoozing. As soon as the weather grows warm they break away the ice from their holes, till these are large enough for the owner to climb through; then Mr. Seal pokes up his head and shoulders into the air, and working his flappers over the edge, hoists himself out.

While Omialik sat watching he happened to turn his glasses on to the broken spire which Kak and Akpek had chosen for their dance. The lens was so powerful it brought the boys right close up, so that the Kabluna could see their funny, jolly faces; it made him almost hear their laughter, and he laughed in chorus. That silent, awkward, pantomime dance was as good as a play. Omialik said to himself: “I will take a photograph of this, and when I get back to New York I can show the American children what merry lads live up on the tiptop of the world.”

He was much too far away to take a photograph at that minute, but he knew Kak and Akpek would be good enough to go back and pose for him if he could head them off on their way home. So he hurried down, thinking no more about seals, and started in the boys’ direction. Once you get into the rough ice it is like walking among mountains; you cannot judge one valley from the next, nor guess what lies beyond each hummock. The Kabluna could see his friends so long as they stayed up on their little sky theater; but after they grew tired of the game and left, they were entirely lost to him. Yet he kept on, for he was on the shore side and they must be coming back soon; and when they got nearer he would attract their attention by calling.

In the middle of the dance Akpek thought of a joke he might play on his cousin, so he said he felt hungry and that it was time to go home, and his hands were cold; and although Kak tried his best to persuade him to stay, he scrambled down from the tower.

Well, of course, there was more room to dance with only one up on top. Kak could not resist giving a final fling or two, and singing again:

“I’m the king of the castle!”

And while he was right in the middle of it Akpek looked up and shouted:

“Bears! Bears!”

Poor Kak! Every last ounce of blood dropped out of his heart. His song broke on a high note. He missed a step and nearly fell. Akpek stood still in an attitude of terror watching him come slithering and sliding down, not caring how he came. And then that cruel boy doubled over and nearly died from laughing because there were no animals at all; he had only called out to frighten his cousin whose fear of bears was known to everybody.

When Kak discovered the trick that had been played on him he felt nasty and said he was going home; and now Akpek could not persuade him to stay. The boys walked along silently trying to find a path between the ice hummocks, and not enjoying themselves a bit. Nothing takes the zest out of things like a quarrel. They felt tired from their day’s climbing, and now only wanted to get home the shortest and easiest way.

“Isn’t that Omialik?” Akpek asked brusquely, pointing to a figure scrambling over the ridge with the sun shining full upon it.

“Don’t know.”

They could tell it was one of the strangers from his long, tailless coat.

“It is—it is!” Kak suddenly cried, brightening. “He’s got his gun. I wish a bear would come so you could hear it bang off! You’d be scared then.”

“Scared—me!”

The man disappeared behind an ice hummock. Akpek continued indignantly: “Say, it takes more than a little puff of noise to scare me! What do you think? Have we been deaf all winter while this ice ridge was piling up here?”

“That’s different—nobody minds ice screeching. The gun makes a terrific bang like thunder, only worse. I tell you I wish we’d meet a bear—almost.”

The last word was hastily added as Kak realized the enormity of his wish. He had an uneasy idea that when a lad wishes aloud he sometimes gets his wish. Akpek’s next words did nothing to soothe him.

“Well, I ain’t scared anyway, and you are.”

“I’m not!”

“You are too.”

“Didn’t I kill an ugrug?”

“That’s nothing to do with bears. I dare say you’d feel all hollow inside if you saw one right now.”

“So would you.”

“I would not!”

The boys continued to argue. They were passing through a small pocket of level ice among lower cakes, while the Kabluna, who had just caught a glimpse of them, ran up a neighboring valley in their direction.

“You think you’re some hunter,” Kak insisted. “But what have you ever done alone? Now I——”

“Ah, cheese it!” his cousin laughed in great good humor. “I guess if we saw a bear right here, without a dog, or a bow and arrow, or a spear or anything, we’d both drop dead.”

“Speak for yourself——”

“Chrrrrrrrrr——!”

The sound stabbing Kak’s sentence sounded much like a cat on a back fence, only horribly loud and near. If you had heard it in the city you might have taken it for the grinding of motor gears; or in the country for an angry gander. To the Eskimos it meant but one thing.

Both boys leaped about three feet off the ice, turned while leaping, and came down the other way round face to face with a huge polar bear. He was standing above them on the ridge, his massive front paws almost near enough to reach out and knock them over. The beast’s small eyes glistened; his yellow teeth showed under a curled lip below his sharp, black nose; and his head swung from side to side as if he were asking himself:

“Which shall I eat first; or shall I tackle both at once?”

The bear was hungry. Luck in catching seals had been poor lately and the cousins looked to him like two juicy, big fellows. They had smelt very good as he followed them up-wind, for Kak and Akpek had played with dead seals while waiting in the village for the day’s fun to begin; and when the pursuer actually saw them he could not refrain, in his joy over a square meal, from giving that nasty bear laugh. It was a fortunate thing for the boys that he felt so jolly. If he had only kept quiet and pounced he would have made sure of one course anyway.

The enemy seemed in no hurry. Hours and hours and hours and seconds he stood gloating, while the boys, hypnotized by fear, stared into his white face, which was not a bit whiter than their own. Goose flesh had burst out all over them like a rash, every hair on their bodies felt as if it were rising on end, their knees trembled, and their tongues stuck to the roofs of their mouths. Kak did give one gurgle, a faint, choked sound that hardly reached farther than the walls of their ice pocket. It was living evidence of his stark terror but as a cry for help must be counted out; yet Akpek, who was positively frozen stiff with fear, lungs and throat and all, and quite incapable of making any sound or moving hand or foot, was mean enough afterward to throw it up to Kak that he yelled.

Now the Kabluna was a mighty hunter. He had killed dozens and dozens of white bears and grizzly bears and wolves and seals and all kinds of beasts and wild birds; and he had trained both his eyes and his ears to miss nothing when he was out in the open. That hard, trilling noise, violently rasping the youngsters’ nerves, had reached him faintly while climbing the other side of the ice ridge. In an instant he was tearing forward, unslinging his gun from his shoulder as he ran.

He saw the bear first—a yellow-white blot between the shimmering snow-covered pile and the blue sky; then Kak’s wheeze of agony drew his attention to the human prey below.

Crack!

The huge animal was gathering himself to spring when the bullet tearing into his shoulder upset his calculations. He didn’t know what had hit him; but he lost his balance and instead of landing on top of the boys tumbled heels over head at their feet. That was the most frightful moment of all, when they saw him coming and thought a thousand pounds of white bear was bound to crash on to them. But the abruptness of it broke his spell; Akpek and Kak were dashing to the Kabluna for shelter before Mr. Polar Bear could scramble to his feet and make connections.

The whole situation had reversed in a twinkling. The bear, from having all the best of it, was now much the worst off. He was down and the boys up. His fine seals had escaped, and a third strange animal, with command of this queer, stinging, long-distance bite, was standing aloft and just going to do it again. Dumbly the poor beast looked up, measured his foe, and in mute fear turned to fly from there; but as he turned Omialik’s rifle cracked again, and a bullet through his side, entering his heart, put an end to all his hunger. He proved to be a very poor, thin old bear and the hunter felt almost sorry to have killed him; but the boys talked loud and fast, bubbling over with excited thanks.

“It is lucky I came along right then,” the white man scolded. “You youngsters have no business to be so far out here alone, without weapons or dogs.”

He felt cross because it seemed too bad that such jolly kids should take any chances on ending up as a bear’s supper.

What to do next was now the question. Somebody must mount guard and keep the foxes off their fresh meat—poor as it was it would feed the dogs—and somebody must run quickly to the village, and send help out to take the carcass home. A polar bear, which can be easily two or three times the size of a lion, is often toted home by being turned on its back and drawn along with a rope fastened through holes in its lips and around the snout. But Omialik thought this would be too much for his young companions over all that rough ice, so he allowed Akpek to choose jobs. After some argument the boys decided to hurry on with the news. Going ahead across the ridge was a terrible trial, for their nerves had been shaken, but the village offered shelter in the end; and certainly they would be safe much sooner than if they stayed out there while Omialik walked over and the other folk returned. Besides, if any more bears came about the white man could use his gun.

With their hearts in their mouths and their glances constantly darting here and there, front and back, sidewise and up and down the two lads scrambled over ridges, helter-skelter, and rushed across level patches. They did not hunt the easy path now but made straight for home, guiding themselves by a range of high hills inland. Soon they clambered down the final hummock, and went flying across the flat ice, shouting their news long before anybody could hear:

“The Kabluna has killed a bear!”

“Omialik has shot a bear!”

When the village woke up to what was being called it burst into violent activity. Some of the men grabbed their large knives and started at once out over the ice; others waited to fetch their dogs. Akpek entertained a circle with a highly colored version of the whole affair; but Kak turned back after the crowd which was following their freshly made trail to where the hunter waited. He simply could not keep himself away from the wonder of that gun.

Omialik had been busy skinning and cutting his bear, so there was nothing left for the Eskimos to do but quickly load up each with a large piece on his back and start homeward. They made a strange procession coming over the ridge, with these bumpy bundles on their necks, dead-black against the burning sky; for the sun had set and reds and golds flamed all round the wide horizon. The Kabluna walked last carrying his long-nosed weapon. The people would not let him carry anything else. They saw now he was a shaman with a powerful magic that could kill a bear by pointing at it, and dear knows what else he could do, so they wanted to make everything very agreeable for him.

Only Kak and his father really understood about the bullets. The boy trudged manfully along with his share of the bear meat, keeping close to Taptuna; for when a lad has been face to face with a wild animal and in peril of his life, somehow he feels desperately fond of his father. After they were safely on the level road they began to talk about the gun.

“I’m going to learn to shoot,” Kak said in his most dogged voice.

“What is the good of learning to shoot if you do not take your bow when you go among the rough ice?”

“I don’t want a bow—I mean shoot a gun.”

Taptuna grunted.

“I’ve got to go to Herschel Island and learn.... Shall I go to Herschel Island?... When can I go to Herschel Island?”

About five minutes elapsed between these questions, Kak taking his father’s silence for consent.

Then Taptuna spoke. “We’ll see,” was all he said, which, as you doubtless understand, is a father’s speech when he does not know quite what to say and cannot directly make up his mind. Presently he added:

“It is too far for you to go alone. Your mother could not spare you yet. But perhaps we might all travel south this summer.”

“All of us!” Kak scouted the thought. “It would be heaps more fun to go with the Kabluna! Who wants Noashak tagging along!”

His father grunted and walked on silently, planning. A journey across Coronation Gulf and inland to the headwaters of the Dease River would be doubly profitable. The country there abounds in wood. Now wood is very scarce where Kak was living. No trees grow on the southwest of Victoria Island, and the prevailing winds combine with the currents in the strait to carry most of the driftwood on to the mainland. Taptuna had broken the runner on his large sled that winter, and had been terribly put about to find material for a new one. But necessity is the mother of invention in the Arctic as elsewhere—when you must do a thing for yourself you find a way to do it. Eskimos are clever about solving this sort of riddle. Taptuna mourned over the sled for a week and then, needing it badly, set about repairs. Taking a musk-ox hide, he soaked it in water, and folding it into the shape of a plank pressed it flat and even. The next step was to carry it outdoors and let it freeze. This of course it did in a very short time and as solid as any kind of wood; so that Taptuna was able to hew out a sled runner exactly as he would have cut one from timber. When this runner was put in place you could hardly tell the difference between the two; but the new one had a great fault. It would only serve during the cold season. When the sun shone hotly and the snow thawed, the runner would thaw too and go flop—the hide be no stiffer than the skins on their beds.

Taptuna said, “We’ll see,” while he was remembering this broken sleigh, and also that his whole family would need new clothes before next winter. Guninana, like most ladies, had a preference in dress; she considered deerskins the finest and softest for making garments—all their coats, shirts and trousers—everything in fact except their boots, which must be of stronger stuff; and they were sure to find numbers of caribou about Dease River in the late summer when the skins are at their best.

Since he could kill two birds with one stone—that is, supply both their acute needs on this trip, Taptuna decided to go. Kak was at first very scornful.

“Herschel Island or nothing!” he cried, and could only talk of his disappointment.

But later, when he learned that Omialik intended to spend part of the summer at Dease River, and heard the grown-ups planning to meet at Dismal Lake Ford, he decided father’s way was not so bad after all, changed his tune completely, nearly burst with enthusiasm; and bragged about the journey as a great adventure till he made Akpek frightfully jealous.