CHAPTER V

Queer Tales

ON THE way home poor Kak walked right into some very bad luck. It was standing with open arms waiting for him; but I think if he had paid a little more heed to advice, he might have avoided the catastrophe.

This is how it happened:

The whole village got up early in the morning to say good-by to Omialik and his Eskimos, and watch them start away to the southeast where they intended to visit other tribes. As soon as this excitement was over Taptuna prepared to take his leave. They would be a party of three, for a friend called Okak, who also wanted to spend the summer at Dease River, had asked permission to travel with them; and as it would be pleasant to have another neighbor on the ice until they left, Taptuna said: “Very well, come along now.”

Kitirkolak and Akpek volunteered to accompany their relatives a short distance; and this suggestion was hailed with delight. It made the first leg of their homeward journey a sort of joy ride, instead of sad departure.

It was a glorious, sunshiny day, windless and warm for the time of year. The dogs drew a light load, and with one man ahead to encourage them and two for managing the sleigh, both boys were free to run as they wished. Their road led south directly into the sun and seeing this, Okak, who was a timid person and believed an ounce of prevention worth several pounds of cure, put on his eye protectors at the start. Eye protectors are worn to dim the great glare of the snow, otherwise the light reflected from the whiteness all around is so fierce that one’s eyes soon begin to smart and burn and water. These are the signs of snowblindness, a very painful botheration.

Taptuna soon called a halt to adjust his goggles (narrow pieces of hollow wood with a slit for each eye about big enough to slip a silver half dollar through) and Kak should have followed his example. But he hated the things. You can easily understand they are not very comfortable to use. They limit one’s vision to a small line, so in order to see any object you have to look straight at it. Now in following a freshly broken trail you must watch your step, and with these goggles that means you can watch nothing but the path, which takes all the shine out of the day. Wearing eye protectors has about the same effect on a boy’s spirits that a muzzle has on a pup’s. Neither Kak nor Akpek would put them on. This was less serious for Akpek because he would only be out a short time, and did not have to face the strain of a long journey over the snow.

The cousins made great sport together, running races, playing leapfrog, now breaking a road ahead with Kitirkolak or trotting along behind; Kak boasting to his chum of all the fun he expected to have that summer.

The day was so calm and the load so light the party moved at record speed. It seemed hardly any time till Akpek’s father said they were far enough from home and must turn back. Then they all stopped and got together for a last good-by, and Okak noticed the boys’ uncovered eyes. He spoke of it at once:

“You’ll be sorry, mark my words! Snowblindness isn’t any fun. Oh, I know you don’t feel it, nobody feels it till too late. Your eyes are probably strained now.”

“They are not!”

Kak glared angrily at the speaker, and Akpek giggled which made his cousin’s face flame scarlet. They were ready to call Okak a “fraid cat” and a “funk.” Every one knew him for a nervous man, always fussing about something, and laughed at him for it. He was afraid of new places. It was on this account Taptuna put up with him on their journey to the mainland. He felt sure the poor fellow would be too apprehensive of trouble ever to go any place alone. Okak was scarcely a cheerful companion. He showed anxiety at every turn, and was constantly worrying for fear they would not kill seals, or catch fish, or get enough of whatever game his people happened to be living on. The boys thought him a regular old woman. Kak stuck his tongue out at Akpek to express his utter scorn of this silliness about goggles; and determined to go without them all day, “just to show him.” Probably if Okak had not been so famous as a trouble hunter Taptuna would have taken the matter up; as it was the parting from his brother, looking back, hand waving and calling messages, drove the thing out of his head.

Taptuna now chose the job of running in front and Okak managed the sleigh, Kak lending a hand once in a while. The snow was mostly smooth, the dogs fresh, the men in fine spirits—just the sort of morning when it is a joy to be alive! Things went like a well-oiled machine; and Kak would have reveled in every minute of the trip, had it not been for Okak. All the time they were behind together he kept nagging and nagging the boy to put on his “specs.” And, of course, the more he nagged the more obstinate Kak grew, till at last he was so mad at the man, he felt he would rather endure snowblindness than follow his advice; and in a burst of temper threw his protectors away.

Kak was young and had so far escaped this affliction. If he had guessed how much it could hurt he would certainly have been goggled from the word go.

When they camped that night, even before they finished building the house, he began to have qualms. Maybe Okak had been right about “strain.” His lids felt queer, as if they had sand under them. He winked but the sand would not go away. At supper time he was sure the lamp smoked, and examined it carefully on the quiet. There were no signs of smoke, yet his eyes smarted. Thankful for an excuse to shut them he rolled into bed early, and got some rest; but toward morning shooting pains awakened him, and these pains increased steadily till his eyes ran water. Kak’s fighting spirit, backed by shame, prevented him from complaining, though he lay suffering for hours. He pretended sleepiness when the men got up and, working this bluff, managed to loiter in the shelter of the house till the very last minute.

The boy knew now he had been no end of a fool to throw his goggles away. He hated to confess; dreaded Okak’s remarks and his father’s displeasure; and hoped against hope to be able to travel and so avoid all the fuss. By gritting his teeth he managed to start behind the sleigh. The ache was excruciating. The vast snow field glistened and twinkled with a million tiny diamonds where frost caught the sunlight, and every one of them became a little white flame that leaped into Kak’s eyes and burned there. He tried not to look, keeping his glance down to the path; but for all his trying they would get into the left eye. So after a while he shut it and used only the right. That proved soothing, but it had the disadvantage of putting double strain on the working eye. Now the right one commenced to smart so badly he was obliged to shut it and keep it shut. He managed to follow with one hand on the sled, opening the left eye every thirty seconds to peep at the road. It was a very bleary, miserable business for both eyes were running water. Kak tried to shake the drops off. He knew that he was in serious trouble. What a crazy idiot he had been! He grew more and more afraid to confess, and so pegged along the best he could, blinking and winking his tears away, and suffering agony.

Of course Okak caught him at it. He was bound to catch him, for he expected this very thing.

“Stop!”

The word of command rang through the clear air. Taptuna turned swiftly. The dogs stood panting, Kak hung his head.

“Look at that silly child. Eyes like rivers and he will not use his goggles!” Okak shrilled.

The boy jerked his head up and tried to look straight at his father; but it was no use, all the diamonds leaped into one furious white fire blinding as the heart of a furnace. He screwed his lids in a spasm.

“Put on your protectors this instant!” roared Taptuna.

Then Kak had to confess, and his father was very, very angry.

“What made you do such a stupid thing? Do you think it manly or brave? It is not even sane! I am surprised at you—behaving like Noashak! And now what are you going to wear? I cannot lead without mine—that would only mean both of us being laid up.... Tut, tut!”

“It isn’t so bad with them shut,” the sufferer answered. “If you drive more slowly, I guess I can keep along here on this smooth ground.”

Kak was about as ashamed as any boy of his age could well be, for his father had said a nasty and a just thing when accusing him of behaving like Noashak. In fact he was so ashamed that for a while he forgot how badly his eyes hurt, or else pride made him able to pretend. They were going slowly and with both hands on the sled he stumbled along somehow. The pain grew worse and worse and floods of tears kept on running down over his cheeks. He was not crying in the ordinary way. Tears come with snowblindness. Your eyes are so sore that you simply cannot hold them back. Poor Kak had every minute to wipe his face with his mitt; and when he took one hand off the sled to do this he almost always tripped. Then Okak would say:

“There! Didn’t I tell you so? If you would mind older people a little you might keep out of these troubles. But no—you are a willful boy and you have got what you deserve. You are probably in for a severe attack; and all because you would not listen to your Uncle Okak!”

This sort of conversation went all wrong with Kak. He grew angrier and angrier, and his eyes smarted worse every minute; the proof that Okak was right making him angrier still. At last he could stand the twin irritation no longer and barking out:

“Oh, do shut up! Give a chap a rest!” He sat down in the road and began to blub.

“Stop!”

Taptuna gave the word to his dogs and swung around.

“You see how it turns out!” cried Okak. “Just as I told you.”

He pointed to where Kak crouched, for the dogs had gone a short distance before stopping. “If you had made him listen to me, friend, we would have been flying along still.”

Without a word Taptuna ran back to his son.

“Is it as bad as that, my boy?” he asked kindly. Okak annoyed him with his bossy I-told-you-so manner; he partly understood why Kak had thrown away his goggles.

Poor Kak was sitting in the snow with the tears streaming over his face, feeling he had not a friend in the world. He expected to be scolded, and the sound of his father’s voice was such a nice surprise it broke him all up. Now he commenced to cry really.

“I’ve got to get home, and I can’t see! I can’t go any further. I’ll just have to sit here and freeze. I can’t stand this agony! I can’t get home!... Boo-hoo.... I can’t bear it!”

Don’t think Kak a great cry-baby. On other occasions he had proved both brave and resourceful. Remember snowblindness is one of the most painful afflictions possible. It is not really blindness in the sense that you cannot see; but at its worst the eyes are so sore one dare not open them even for a minute to look at anything, and so the sufferer is practically blind.

Taptuna saw at once that Kak’s eyes were in a bad way; but he did not think telling him so would help. Okak had done sufficient croaking for the whole journey; instead he said cheerfully:

“Don’t you worry, old fellow, we’ll get you home all right. Buck up now and take my arm and I’ll lead you to the sleigh. I can make a tent for you on it so that you won’t even know the sun shines.”

Then Kak stumbled to where Okak waited with the team, and his father readjusted the load, making a comfortable little nest for him to lie in; and finally covered him all over with a bearskin so it was almost as dark as night. The air grew stifling hot under the fur rug, and his legs were terribly cramped, the eyes pained and still ran quarts of tears; but his father’s care was so precious to him after being such a forlorn, stubborn, naughty outcast, that the boy really felt almost happy, and kept as still as a mouse, while Sapsuk and Pikalu, going at a steady walk, for the load was not so light now, covered the shining miles.

In this humble manner Kak returned from the journey on which he had started so gloriously and with such splendid company.

There is no cure for snowblindness; nothing to do but grin and bear it. One sits in the house with one’s head covered and gradually the pain goes away. Kak lay indoors with a blanket over his head for two days and Guninana sat beside him all the time trying to amuse him, as your mother does when you are ill. She was busy sewing, for as soon as Taptuna told her about the summer trip, she knew the family must have a good supply of water-boots, so she set to work making them from the skins of small seals. It was Kak who did most of the talking, telling every detail of their visit in the village. This pleased his mother. While she sewed she asked questions, and more questions, for she saw that thinking of his adventures helped to take the boy’s mind off his pain. When Kak told Guninana the story of being chased by the polar bear she was nearly scared out of her wits; and for a minute both were so thrilled they forgot all about his trouble.

Noashak, however, did not allow them to forget long. She would come and stand beside Kak and ask:

“How do you feel now? Are you crying so much? What is it like to keep your head under the bedclothes all day? Can’t you see my shadow with your eyes shut when I stand here by the lamp?”

She meant it partly in kindness, but it always started the pain, and Kak would cry:

“Do stop talking! Do go away!”

And Noashak because she was selfish and liked to tease would not go away, but tried to crawl in beside him under the skin.

Kak shoved her off and she began to howl; so Guninana had to contrive quickly an errand to send her on just to get rid of her.

“I think it would amuse Kak if we had a party to-night and told stories,” she said. “You run, Noashak, and tell Hitkoak’s family and Okak to come here after supper. We will see who can tell the best story, and the one who tells the best will have a reward.”

“What reward?” demanded the children in one breath.

“One of the caribou tongues that the Kabluna gave us.”

“Goody! Hurrah!”

Caribou tongue is about the nicest thing Eskimos ever get to eat. The white man had saved them and repaid hospitality with a treat—like sending his hostess a box of candy.

Noashak clapped her hands and ran to spread the news, leaving her poor brother in peace. Then Kak said, “Mother, you’re a trump,” or the nearest thing to it in Eskimo, which made Guninana smile all over her face, for even parents like to know their trouble is appreciated.

Fortunately Noashak got so interested in playing with the neighbor girls she stayed over there, and did not return till they all arrived calling from the tunnel:

“We are Hitkoak and Kamik and Alannak and Katak and Noashak and Okak. We are coming in.”

Eskimos have difficult names and a child may be given twenty of them like a foreign prince, but each person only uses one, without anything to indicate the family relationship.

This is the story Kamik told, and everybody agreed it took the prize.

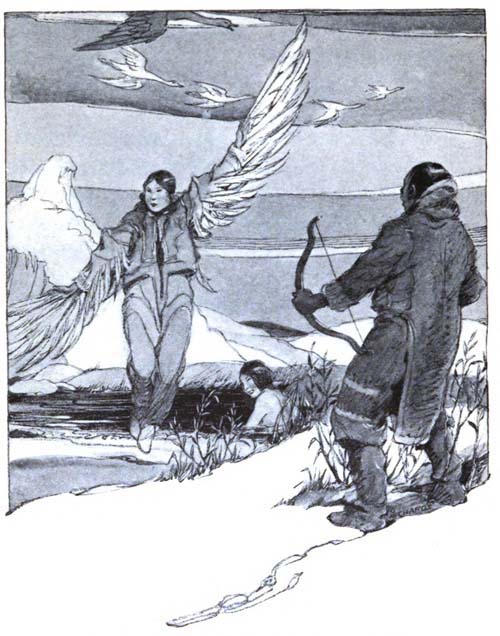

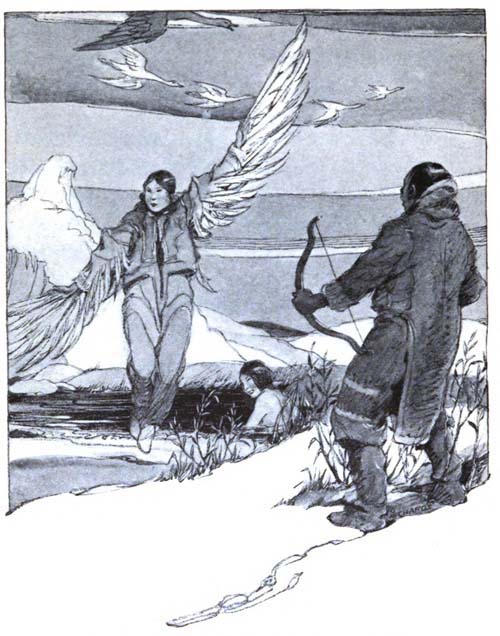

Once upon a time a young man was lying near a pond waiting for some caribou to move away from a very open place where they had been feeding, so that he might creep up on them and shoot them with his bow and arrows. Instead of moving on the caribou lay down. At this the hunter felt terribly disappointed for he knew it meant waiting ever so much longer, and he was tired of waiting. He had just about decided to give up and go and find other caribou in an easier position, when a flock of wild geese flew over and settled on the edge of the pond. They looked pretty fluttering down from the blue sky. The youth watched them idly for a while, then he said to himself:

THE HUNTER COULD NOT BELIEVE HIS EYES.

“Ah, I will have some of these geese to take home.” And he drew an arrow out of his quiver.

But before he had laid the arrow across the bow he saw a strange sight. The geese began to take off their feathers. They took them off like dresses, folded them up neatly and laid them on the shore; and as each one laid aside her downy dress she turned into a beautiful girl, and ran into the water and began to splash and swim about.

The hunter could not believe his eyes. He rubbed them hard and looked again. The girls were all in the water now having a good time. Was it possible they had flown over like geese? He did not know what to make of it, but finally he decided they were girls dressed up as geese, and he thought to himself:

“One trick deserves another; and here is a fine chance for me to play a joke.”

So he crept along very carefully without making the slightest noise till he got near enough to suddenly leap up and rush and seize their feathery dresses. When they saw him do this all the girls cried out. But the hunter only laughed and ran away. Then they called and called to him to come back and give them their clothes; they cried and pleaded. And a great number of wild geese came flying overhead, calling—calling. The sky was quite dark with them till the youth grew afraid and ashamed and brought back their feathers. As he handed each dress to its owner she slipped into it and was instantly a goose again, and flew away to seaward with a flock of the wild birds. The hunter, who couldn’t make it out at all, stood staring after each one; while the girls who were left waited crying for their clothes, and wild wings beat overhead.

When it came to the last girl, she was so beautiful the youth decided he could not let her go.

She begged and prayed: “Oh, do let me fly away with my friends! Do let me go—do let me go!”

But the hunter said: “No. You are the most beautiful creature I have ever seen, and you must stay and be my wife.”

“I do not want to be your wife! I do not want to stay!” the poor girl cried.

But he would not let her go. So the last of the geese got tired waiting for her and flew away. Then he took her to his house and she became his wife.

Now when the bird-girl had been the hunter’s wife for many months she grew weary of living in the same spot. She longed to fly about in the open sky, to hover and swoop and sail, and most of all to find her lost companions; so she began to look for goose feathers, and when she found any she took them carefully and hid them in her house. Of course her husband knew nothing about this. While he was away hunting she used to work sewing the feathers into a dress. And finally one day, when the dress was finished, she carried it outside and put it on. At once her powerful magic turned her into a goose, and she flew to seaward.

That evening her husband returned joyfully, for he had killed three caribou. He ran calling out the good news to make her happy. But when he came into the house and found it empty and cold, all his gladness turned to bitter grief; he sat down with his face in his hands and cried. And the next morning early he went out and skinned his caribou, brought home the meat, dried it, packed enough to feed him for a long time, and started out to look for his wife.

He walked and walked and walked over the rolling hills, but he never saw anything of her at all. He looked in every pond and lake and wandered by the rivers. When he saw geese black against the sky he would crouch down quickly and call “Lirk-a-lik-lik-lik! Lirk-a-lik-lik-lik!” for that sounds like the goose call, and he hoped she might hear and relent and come back to live with him. But she never came, and he never heard anything of her.

One day the hunter’s travels brought him to a mighty river on the bank of which sat a man making fish, adzing them out of pieces of wood and throwing them into the water. Now this man was called Kayungayuk, and he had a strong magic. You can believe it for the fish he made out of the wood swam away as soon as he threw them into the water.

The hunter, seeing this, thought: “Here is somebody who can help me.” So he approached the stranger and said: “I am a poor man who is looking for his wife.”

But there was no reply.

“Can you help me to find my wife?” he asked.

The man continued cutting his fish out of pieces of wood and naming them as he threw them in the water. “Be a seal,” he commanded a large piece, and the wood turned into a seal and swam off. “Be a walrus,” he said to the next, and it became a walrus. When he took up a handful of chips they turned into salmon. “Be a whale,” he commanded his largest model, and it turned into a whale. He made all the swimming things on the flesh of which men live, and the hunter watched him.

But after a while the watcher grew impatient and said: “I will pay you if you will tell me where my wife is.” He urged the man to tell, and the other did not even look up. Then the hunter offered to give him his adze if he would tell him what had become of his wife.

The man kept right on chopping, but now he mumbled to himself: “Ulimaun. Ulimaun.” (Meaning “An adze, an adze.”)

So the hunter felt encouraged, and opened his tool bag which was on the ground beside him, took out his adze, and gave it to the man as a gift.

And the man said: “Your wife is tired of being a goose, she has turned back into a woman, and she is over there on the ice fishing—to the west.”

Now suddenly it was winter and there was ice on the river and over the ice deep snow; but all this did not frighten the hunter for he knew Kayungayuk’s magic was working; and he went into the river under the ice, which was the quickest way. When one has magic and goes into the water, one finds that the water does not reach to the bottom of the river or sea. There is a space below over which the water stretches like a tent roof—like the ice, only thicker. And so the hunter was able to walk across the river bottom under the water and the ice.

The young caribou hunter had never got over his habit of playing tricks. Because of his wife’s being lost he had seemed very sad and dull for a long time; but now he was going to get her back he turned jolly again. As he walked across the bottom of the river underneath where the people were fishing, he saw all their fish hooks hanging down through the water, and he couldn’t resist giving each hook a little tug like a fish biting—just to fool them up there. The people felt the jerks and began hauling in their lines to catch the fish. Then the hunter laughed and laughed.

He came to his wife’s hook and gave it a little tug. But when she hurried to pull in her fish, he caught the hook strongly with both hands, and she pulled him up.

Kamik finished abruptly, yet her audience seemed quite satisfied; for when Eskimos come to the end of their yarns they stop, without bothering to add our traditional phrase: “And they lived happy ever after.”