CHAPTER IX

Missing

“COME here! Come here, Noashak! It is better that you stay here.”

Guninana stood at the tent door. Her face, as always now, wore a shadow of anxiety. She called, but Noashak would not mind.

The child ran a little way to where her brother sat and creeping up behind threw herself on him, clapping both her hands over his eyes so that he could not see.

“Get off!”

Kak was busy making arrows. He had determined to have an extra good supply for their northern trip across the prairie. “So I can shoot at every bird and beast I see,” the boy proclaimed, adding in his heart, “and maybe kill a grizzly bear.” He sat cross-legged on a mossy stone, and at the moment his sister jumped on his back he was measuring an arrow from his chin to his middle finger tip. Noashak’s sudden impact drove the sharp end into his flesh. Kak turned on her angrily.

“Why can’t you keep off me, kid! How is a fellow ever going to get ready for a journey with you bothering ’round?”

“I want you to come and play.”

“Play! Can’t you see I’m busy—this is important work!”

“But I want to play,” insisted the child.

Kak was silent.

“Brother, please be nice and play,” the little girl coaxed, looking at him through her lashes, dropping her voice to a small murmur.

She stood before him, winsome and pathetic, with her long hair hanging in two braids over her shoulders and her hands clasped behind her back. But the boy was gazing ruefully at his arrow. Her blow had broken it.

“Get out,” he answered. “Can’t I ever have any peace? Leave me alone!”

Noashak, who happened to be in one of her rare good moods and expected everybody else to be good too, looked for a second as if she were going to cry; then she turned swiftly.

“I will play with the hares and marmots,” she said, “for I have no brother and the children are all away.”

With that she began to run. Her little brown legs twinkled over the ground toward the thickest woods where spruce held out protecting arms. Her clothes were of dappled fawnskin and once among the lichened rocks and checkered shadows she was as completely hidden as a fawn.

Kak replaced the broken part and trained his eye down the spliced shaft. His conscience troubled him. “You might have played a game with your little sister,” something seemed to say; and reason answered: “But how is a chap ever to get a day’s work done?” He rubbed his sore chin gingerly and measured the arrow again. Quite right. Yet he did not hold it up for his mother’s approval as was his wont. Guninana had seen that roughness; had looked at him reproachfully. The boy felt unhappy and ashamed. He got up and walked away to the working place, where all the wood he and his father had hewed stood drying. Taptuna was there putting the finishing touches to his new sled. Mere sight of that sleigh was enough to raise anybody’s spirits.

“A beaut’!” Kak cried. “How Sapsuk and Pikalu will make it flash along.”

The owner glanced up pleased and satisfied. “Yes. It’s a fine sleigh, and I’m glad it’s done. Now just as soon as the snow comes we can be off.”

No need to explain why he wanted to get away quickly. The shadow of anxiety on Guninana’s face was reflected in her husband’s. “Unfortunately the snow is late this year; still, in a week or two we can count on the first flurry.... Got to be in time for the trading at Cape Bexley,” he added more cheerily.

Kak brightened. “Golly! I’ve got some fine pieces for Kommana. Look here!” He slapped a proprietary hand on one broad board cut from the heart of the largest tree they had found. “The snow shovel I promised him. That dog will be mine certainly if they show up at the Cape.”

“Yours—eh? Who helped cut the tree; and who is going to feed the dog?”

“Now, dad! We’ll go halves on him, of course, in working and feeding—but he is to be mine, if we get him. It’s a promise—isn’t it a promise? Say it’s a promise,” Kak teased.

Taptuna laughed. “Oh, all right. I promise—if we get him. Lend a hand here with this lacing, will you.”

He gave the end of the long thong to Kak; and the boy, wreathed in smiles, for he had just been granted one of his most cherished dreams, pitched into work whole-heartedly. So the hours slipped by in pleasant comradeship and Kak never once thought of that bunchy figure he had watched running off to play with the hares and marmots.

It was late in the season now. Their continuous Arctic day had passed. The sun sank at midnight below the horizon leaving it dark for three or four hours. About sundown Guninana came to the working place, her face graver than before.

“Have you seen Noashak?” she called from a distance; and Taptuna without looking up called:

“No. She has not been here!”

“Then she is lost.”

“How’s that!” Noashak’s father stopped work, straightened his long back and gazed in astonishment at the speaker.

Guninana had come close. She dropped on a stump wearily, looking at her husband with troubled eyes, but addressing her son: “The child has not been home since she ran to you, Kak. What did she want then? What did she say?”

Both turned for the reply and the lad’s glance fell before his father’s.

“She went to play with the hares and marmots,” he muttered, kicking at a root.

“Into the woods—and you did not prevent her! Oh, son!”

“Well, how was I to know——” Kak began impatiently, and stopped. For he saw something in his parents’ faces that caught at his own heart.

“Foxes, I never thought of it! I’ll go and hunt for her—I’ll call. Don’t you worry, mother. I know all the places she plays in.”

“I have hunted. I have called,” Guninana answered miserably. Then roused herself to cry after the boy. “Don’t go too far. It’s growing dark; and there is no sense in your being lost also.”

Taptuna started at once in another direction, and between them they beat the near woods calling “Noashak!” and calling to each other; keeping in touch. Then, as the twilight deepened, his father ordered Kak home. They both came in gloomy and fatigued and sat down without a word. Okak had finished his supper and brought sticks to replenish the fire. He was silent, observing. Taptuna accepted a horn of soup, but Kak refused. Shame and self-reproach were eating at his heart. He had hunted for Noashak in a fever of remorse, rushing up and down the woods calling her name aloud; promising through set teeth all he would do for her and be to her if she only came back alive. Now he threw himself supperless by the fire and fell asleep.

“Where is the little one?” Okak asked presently. “I have not seen her with the other children to-day.”

There was a noticeable pause; then Guninana answered, trying to make her voice sound ordinary. “She went to play and has not come back yet.”

“But the others are back long ago!”

“She went into the woods.”

Taptuna’s voice sounded rough for his proud soul was full of alarm which he would have liked to keep from Okak.

“Ah—into the woods—and she has not returned.”

Each slow word was a knife twisted in their hearts. Dead silence followed. It is not necessary to talk when all know what the others are thinking. At last Okak broke out violently:

“This is exactly what I expected! We had better rouse the village, neighbor, and go in pursuit.”

His use of that final strange word stabbed his belief home.

“Nonsense!” protested Taptuna, but the familiar exclamation lacked force. It seemed to drop away into darkness. Okak’s voice continued harshly:

“Ah, yes! You have been saying ‘Nonsense, nonsense’ to me all summer. But now this is not such ‘nonsense’ if the Indians have taken Noashak. And why should we suppose they haven’t got her? Has any child ever strayed from the camp before? Not one! Certainly they have enough intelligence to return if they are not prevented. And what else could prevent her—who else but your precious red traders! It is fortunate if they have only carried her away, and have not already taken her teeth for their children’s toys and her hair as a decoration.”

“Don’t!” Guninana cried shuddering.

Though his speech was cruel she knew Okak as a faithful friend. He had already put on his stoutest pair of boots and was selecting his best arrows with trembling hands.

“Where is Omialik?” he asked.

“Hunting.”

“It is as well for him that he is hunting!”

This threat sounded so sinister the others were quite taken aback. They had not expected blood and vengeance of the timid Okak.

Seeing Taptuna hesitated the little man took another tone, urging: “Come, neighbor, there is no time to lose. A volunteer party must start for the Indian encampment at once.”

When one person makes up his mind about anything so very positively, he is apt to carry conviction to others. Taptuna did not know what to think. Okak’s turning into a man of action was an uncanny business in itself. It made him feel as you would feel if a statue on the street corner suddenly came to life and commenced issuing orders. Circumstances seemed to prove his fears and hatred just. They had held the thought of Indians from the first, though unconfessed; and nothing came to mind to overthrow their neighbor’s reasoning. Besides, both realized that neither Okak nor the village knew the worst—the fact of Jimmie Muskrat’s trickery.

“Perhaps—perhaps! It will be better to go down and see—and be sure,” Taptuna muttered.

“Anything is better than nothing. Do something!” the mother moaned.

At that her tall, competent husband turned and meekly followed his fussy companion across the open ground to the mottled tents looking so much like rocks under the pale radiance of the autumn moon.

Kak awakened to the menace of an empty village, deserted work, his mother’s grief, and the frightened faces of the women who had come to sympathize. Okak’s accusations had convinced them. They told the boy without a shadow of doubt that Noashak had been carried off by Indians and the men were gone after her. All this tragedy springing out of his one moment’s ill nature was more than Kak could stand. It seemed very unfair. Nobody spoke a word of blame, but he felt they all knew it was his fault, and unable to meet their looks he stole away and hid amid the underbrush till the search party should return.

When he heard them coming he crept out hopefully. But the worst news was already leaping from lip to lip by the time he got home. They had found the camp site but no campers. The remains of the lodges were freshly deserted, and it was all too evident the Indians had run away with their prize. Taptuna, nearly crazy, had insisted, against his people’s advice, on immediate pursuit. He would have started alone had not the Kabluna’s two Eskimos volunteered to go. The three were following hot on the redskins’ trail.

Kak revisited the underbrush and gave himself up to despair. He had felt remorseful last night; now his heart sank into his very boots. Omialik being away added the last drop of bitterness to the cup. This distress was purely unselfish. Much as the boy longed for advice and comfort, he really wanted his friend to come back and clear his own good name. Women in the village were already telling how the white man had been party to the whole plot; asking, “Aren’t his Eskimos glad for an excuse to escape?” They said Omialik would never come again, would never dare to show his face. This hurt Kak as nothing else could have done. It was difficult to keep doubt out of his valiant little soul when doubt seethed all around him. Of course he did not believe their lies, but the sting and strain of loyalty which stands against the mob, and the soreness which endurance leaves in the human heart are fierce emotions for a child. Kak writhed in double torture; then gradually his mood shifted from crushed humiliation to stern resolve. Since it was his fault Noashak had fallen into the Indians’ hands, it was plainly his duty to rescue her; and it was his privilege to defend Omialik—to warn him.

Lying on his back, staring up into the blue sky, Kak thought it all out carefully. He would go after his sister. No need to waste time scouting around by the deserted camp, he could strike boldly across country till he reached the eastern end of Great Bear Lake, and once there he would find Mr. Selby. If Mr. Selby proved friendly and asked the Indians living about him to help, then Kak would be able to send a warning to Omialik, for his friend must know his plans.

Fired with ambition the boy crept back to their tent, made up a small package of dried meat, took his bow and arrows—all his new ones that he had been so eagerly laying aside for use on the homeward journey—and stole away.

Guninana sat among the neighbors in the largest tent, where a shaman in a sort of trance, with wild contortions and weird words, sought Noashak. Kak kept out of it. He did not want to be stopped and questioned. “Mother will understand when she sees I have taken these arrows,” he thought, as he ran on silent feet down the nearest path. Kak too looked like a deer in his deerskin clothing. The trees held out welcoming arms, and the rocks were mottled with grays and browns. In a few minutes the wilderness swallowed him, leaving no trace.

He struck boldly south. The forest consisted mostly of slender spruce in scattered formation, so at first he made good progress. But when he had gone perhaps six hours’ travel the woods grew denser; thick enough to try both his strength and patience. He was thinking about making camp, sitting down for a rest and a bite of food anyway, when a rustle in the branches set his pulses throbbing. The forest lay still but not silent; a light wind from the north, sighing continuously, swayed the tapering tree tops; but this noise he heard was different from any wind noises—a persistent rustling through the alders. It was sunset and darkening here in the woods, and poor Kak, who had been like a lion a moment before, felt all the courage oozing out of him. He fell on one knee behind a log. The sound came nearer, grew unmistakable. Some large body moved through the copse. The young hunter laid an arrow across his bow and waited with every muscle taut. On it came, near—so near he began to tremble for his safety. What if a grizzly bear loomed suddenly out of the dusk above him! The boy knelt trembling, with distended eyes riveted on that spot where the stealthy noise seemed to approach.

“Whatever it is, it’s coming so close I can’t miss,” he thought, and bent the bow. Swiftly the bushes parted, letting a dark mass tower over him. It stood with its back to the waning light and might easily have been an animal by its shaggy outline; but Kak saw. His muscles relaxed in sickening reaction as the human form sprang at him over the log and seized his arm.

“Good gracious! Don’t kill me!” cried a familiar voice.

“Omialik!”

Two sorts of relief rang in that cry. The Kabluna was on his way back—then they had all told lies, lies, lies! The boy’s sorrowing heart rushed out to his friend, whom he had so nearly shot; he threw himself into the white man’s arms and cried like a baby.

“Why, Kak! Why, Kak! Were you lost? Were you scared?”

Omialik repeated over and over as he patted the sobbing youngster: “Brace up. It’s all right now. We’re not many hours from home. Come—come! Brace up.”

“It isn’t me,” cried the boy. “It’s Noashak. She’s been stolen by Indians!”

“What nonsense!”

“That’s what dad said, but she’s gone just the same. The men went down to the Indians’ camp to hunt for her; but the Indians are gone. And you were gone too! The women are telling that you were in league with Muskrat.”

“Great Jehoshaphat!”

This was startling news—bad news—bad enough to make the white man want to hear it quite correctly.

“They’ve been to the camp, you say, and found the Indians gone?”

“Yes, and father is following with your Eskimos: the rest of the search party came home.... It is all my fault Noashak’s lost. She ran away into the woods because I was cross with her; so I thought I’d better try and bring her back. And I was going to the lake to leave a message with your Selby about how mad the village is, so—so that you wouldn’t go there without your gun.”

“You intended to warn me? That was kind.”

Omialik’s eyes grew soft. One glance at his face was sufficient reward for Kak. Look and words together acted like balm on the boy’s bruised self-esteem. As he sat by his friend, eating dried meat and telling him every detail of their scare, his spirits rose. It seemed possible Noashak had never been near those deserted lodges—that they might all have been wrong. And he was prepared to accept the white man’s judgment when it came.

“I don’t believe Muskrat had anything to do with this business. It would be best, my lad, for you and me to return to the village and set matters right there. If your father is not back—if they have no news—we can start systematic search instead of running off on a wild goose chase. Maybe the child is only lost. What made you so sure she was stolen?”

Kak thought hard. “The women told me so,” he answered. “And Okak told them so. He was positive.”

Omialik smiled. “Okak was always crazy-frightened of Indians.”

“But what he said is true. Noashak would certainly come home from her play unless something was keeping her. The kids never go far.”

“Well, something else might have prevented her. Suppose she had fallen, or——”

“Don’t!” cried her brother in the same tone Guninana had used. “I’d rather it was Indians than animals!”

The boy found himself suddenly, vividly, plunged back into that terrifying moment before Omialik appeared, when his courage oozed out of him, his hair stirred on his head, and cold sweat started from every pore. He tried to imagine his little sister so amazed, surrounded, trapped by some wild beast of the woods—but it was too awful.

“Come on!” he cried, springing to his feet. “We’ve got to get ahead!”

They had been talking a long time and it was now dark with a cloudy sky. The white man’s instinct was to camp and wait for daylight. But Kak urged him so to “Come along,” to “Try,” that he gave in against his better judgment, and they began scrambling through the thick brush. It was slow, heavy travel and after an hour’s effort, Omialik stopped.

“No use, Kak, we are only losing our way and getting all mixed up. I haven’t any idea which way we are heading. This seems a likely spot, so far as one can feel, and I hear water. Let us camp and wait for morning.”

Kak was about ready to drop from fatigue and silently agreed. They built a little fire for the night was cold, and ate some more dried meat, drinking great refreshing draughts from the spring which Omialik’s quick ear had not failed to note.

“What is that strange smell?” asked the boy, sniffing the keen, autumn wind.

“Caribou, or I’m mistaken. My, but it’s strong! We must be close to an enormous herd—the first caribou I have struck in three days, and it’s so pitch-black I can’t see my hand before my face! What rotten luck!”

“Well, I’m glad it is dark! I’m too tired for hunting,” Kak answered, and throwing himself on a bed of moss, immediately slept.

The young hunter awakened in the early morning of a quiet lowering day. Caribou scent hung heavy in the still air. He noticed a strange vibration through the ground, heard the thud and rustle of trotting feet; sat up and shook his companion.

Omialik rolled over sleepily, opened one eye, grew conscious also of that odd trembling in the ground, opened the other eye, and lay staring into the clouds.

“Whatever is it? Do you feel—do you hear?” asked Kak in excited whispers. “Yes, and I smell it too!”

The Kabluna rose on one elbow. “Must be caribou traveling,” he said. “A large band—an immense band!... Listen to the ripple of their feet.... Wonderful! Let’s get out of here to some place where we can see.”

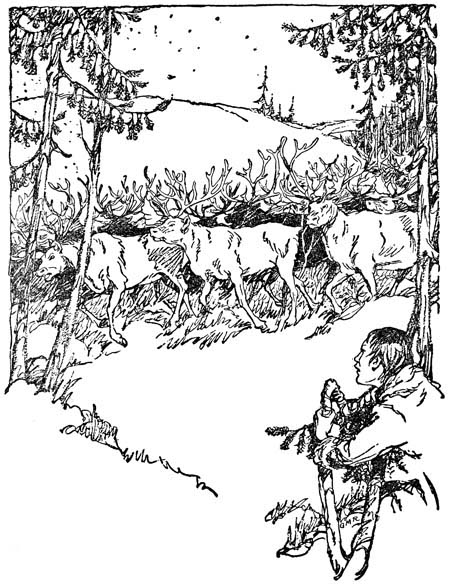

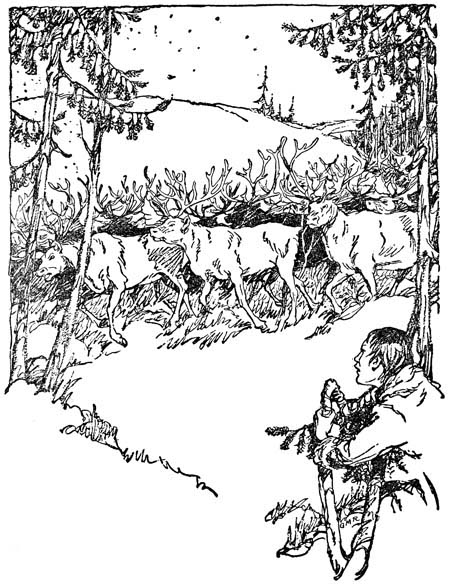

THE WHOLE PLACE SEEMED TO BE A MOVING RIVER OF DEER.

He scrambled up and pushed through the copse, Kak following. It might have been an eighth of a mile to where the trees thinned. There an unbelievable sight met their eyes. Caribou were marching past in solid columns, two, three, or more abreast. These columns were only a few yards apart and extended as far as eye could see into the sparse woods. The whole place seemed to be a moving river of deer.

“I wonder how long it’s been going on,” the white man exclaimed. “My word, I’m glad we wakened before they all passed! I wouldn’t have missed this sight for anything!”

They stood there a long time waiting, expecting the herd to peter out, its spectacle coming to a sudden stop like a battalion marching by. But the solid columns continued to pour on—the river flowed and flowed.

“Marvelous!” sighed Omialik.

“Perhaps we can get along through the woods,” Kak suggested; for the fascination of the marching host paled a little when he recollected his sister. The white man could not bear to tear himself away. This was the grandest exhibition of the riches of the north he had ever seen. He wanted to look and look, convincing himself of its reality, so that when he returned to his own country and people talked about “those cold waste regions,” and “the barren Arctic,” he could remember this and say: “You are all wrong. Hundreds of thousands of animals roam over that so-called desert; birds and butterflies and insects, millions of insects, infest it; and caribou travel there by regiments.” Noashak’s peril left him no choice but to turn his back on the deer. They tramped through the copse where they had slept. In its thickest part the sound of running feet died down a little, then it swelled again, grew sharper, more distinct.

“Foxes!” cried Kak. “I believe we’re coming on another lot over here!”

It was so, their copse proved to be an arm of the forest thrusting itself thickly down along either side of a small stream. And they broke out of it suddenly, opposite their first stand, to find more solid columns of migrating deer moving steadily past. These animals walked as close one after the other as possible, while row beyond row lined all the visible area.

“Aren’t you hungry?” Omialik said. “Shall I kill some fresh meat for breakfast?”

“First rate!” Kak answered. Then glancing at the closely packed animals, “But it seems a kind of shame!”

“Good for you! That is the right sporting spirit, my boy; stalk your game, don’t have it driven. However, necessity is master here—and I don’t believe one will be missed. What a chance this to kill a whole winter’s food supply! If only my men and your dad were along to help us build caches. It would be waste to slaughter the poor things and leave them for wolves.” Omialik stood watching, then he glanced at his companion. “Suppose you do the shooting this time and save ammunition.”

Excitement fluttered up the boy’s nerves; he only hoped he did not show it as he anxiously selected one of the new arrows and bent his bow. Kak had never killed a deer, and there was little glory, he knew, in killing at such easy range; yet he got a thrill when the large buck he had picked staggered and fell among the herd. Omialik’s praise was sweet.

They built a fire and feasted on roast ribs, making a quick meal of it, for Noashak’s little figure seemed always to be flitting before Kak’s eyes.

As the caribou were now moving against a shifted wind, almost directly away from the village, the man and boy were able to walk between two columns when chance offered breaking through one line into the space which divided it from the next, walking there awhile, and at the first opportunity repeating the maneuver; always keeping to the right and slowly working out of the herd. After they had left behind the last straggling groups, a couple of hours’ fast travel brought them home.

By late afternoon, as they neared the village, the brother began to worry. “We won’t have much daylight for searching,” he grumbled, “and I know how it will be, everybody crowding around gabbing, trying to get in a word with you or at you—delaying us no end.”

The white man was endeavoring to cheer him by promises of a speedy departure; when who should come running to meet them but Noashak herself.

Kak’s throat choked up at seeing her. “What happened?” was all he could say.

The little girl seized Omialik’s hand and jumped around and rubbed on him in quite her old, bothersome manner.

“Don’t act so much like a chipmunk. Come. Tell us your story!” He laughed at her mauling, and captured both small hands in one large glove. “What happened after you ran away to play with the hares and marmots?”

“I wanted to go right off where Kak would have a lot of trouble finding me, because he was mean. You were mean, Kak! I ran and ran till I was so tired I lay down—maybe I had a little nap. When I felt rested and thought you had been looking for me long enough I tried to go home; but the sun hid behind clouds and I didn’t know which way was home, and still I kept on going. Then numbers of caribou came feeding near by—more and more and more. It began to grow dark and I cried. That didn’t stop the darkness a bit; so by and by I ceased crying and looked around for a bed. There was a nice, low island of rock with three spruce trees growing on it, and smooth ground all covered with moss, and I thought: ‘That will make me a fine house.’ With such a lot of animals around I wanted a safe place. I climbed up. It was almost dark and the night grew blacker and blacker for a while; but presently the clouds blew away, and the stars shone and the moon. There was an awful smell and the sound of many animals running. I could see antlers like trees rushing past, and the wolves howled, and——”

“You were scared and howled with them.”

“Yes, I did,” the child answered boldly. “I cried myself to sleep. When I woke up it was bright day and the whole world was covered with caribou—such lots and lots of caribou, all going in the same direction! There were wolves among them and I was frightened to go into the herd, so I sat still and waited. I was on the island with an ocean of deer rushing by. They kept me on the island. I had nothing to eat but berries, and I cried and hoped you would soon come to find me.”

It was so. That day the child had lain alone on the dry, vibrating ground under low clouds, and watched the cold, blue evening fall; while those gray, shadowy, moving legs and tossing, antlered heads came on, and on, and on. The thud, thud of running roofs made a strange lullaby. The wind had risen to a sighing moan, and now that night drew in wolves, racing with the herd, howled dismally.

All through the darkness deer continued trotting by, and to the tramp and tremble of their small, innumerable feet Noashak waked a second time.

She felt very lonely and sad as well as hungry, and scarcely thought it worth while to sit up and look at those interminable creatures. Imagine her joy, then, on finding one edge of her rock quite free—luckily for her the edge toward home. This was because the breeze had shifted, making the caribou, which usually travel into the wind, alter their course. Gradually, while the captive slept, the columns had bent westward till the whole, vast herd was swinging down on the far side of her island. The instant she took it in Noashak jumped up and hurried out of prison.

“I’ll never, never again be so naughty as to run away!” the child promised, shaking her head violently; but her seriousness lasted only five seconds.

“What do you think?” she cried, hopping on one foot. “Okak said Indians had carried me off. I wish they had! Then I could have seen their lodges, and I wouldn’t be back till father saved me, and killed Jimmie Muskrat; and everybody would still be scared.”

“What! Do you like to frighten us, you mischief?”

“Course I do! It’s lots of fun. Being away is tiresome; but it’s grand getting home! Everybody gives you things—see. Here’s Okak’s charm against evil.” She held up a dried bumblebee hung in a bag on a sinew about her neck. “Mother says I look too much like a fawn and she has promised to make me a coat with bright red trimmings if we can get the ocher at Cape Bexley. Do you hear, Kak? I’m to have a new red coat! It’s so I shall never get lost any more. But I’d like to be lost sometimes if I could see all those caribou. Nobody believes I did see them. They say I dreamed it—but I really and truly did.”

“Bully for you! Stick to it,” Kak cried. “They were real, all right, and you saw them. Don’t let the villagers humbug you out of that. We saw them, too, and we killed one and ate it—that’s proof it was real!”

“Only one, worse luck!” Omialik exclaimed. “But now you are safe, miss, we’ll hurry back and lay in some meat. Where is your father?” he asked; for there would be need of all hands to skin and cut up the deer.

“Dad’s still looking for me, and your Eskimos are with him. I guess they’ll be pretty anxious by now.... Oh, I do hope they’ll come here soon so we can start to Cape Bexley—I do want my little red coat!”