CHAPTER X

Homeward Bound

ALL very well to talk so lightly about going to Cape Bexley; when it really came to the point, leaving meant taking leave and this was a bad business. Kak’s heart broke, for his friend, Omialik, stayed behind. It was the white man’s intention to return down Horton River to Franklin Bay and go from there to Banks Island—a long and dangerous journey into the unknown. The boy burned to accompany him.

“Later on, later on, when your legs are a bit longer for walking,” the explorer promised.

Kak tried to smile, tried not to show the hollow feeling this separation planted in the pit of his stomach; but it took moral force. He gulped.

“Brace up, old chap.” The Kabluna patted his shoulder. “I’m coming back, you know. You will see me in Victorialand again—unless by then you have gone to Herschel Island to learn to shoot.”

Talking about impossible dreams as if they were bound to happen makes them seem jolly real. Kak managed to choke back his sorrow, and freshly convinced that life was a grand adventure, ran after the party who were already trekking north.

Crossing the prairies with all their gear and trade goods, the wooden dishes, pails, lamp supports they had made, and pieces of rough wood piled on the sled, proved an entirely different experience from their tiresome, hot, hungry tramp southward. The new sled ran lightly on snow ample to cover the ground and not too heavy for walking. Taptuna was careful to pack a good supply of food, and halfway across the tundra they found their old cache. All laughed heartily to think how much worse they had needed it in the summer than they did now.

With favorable weather and little time lost hunting they made a record trip. Spirits mounted at every mile. Guninana sniffed the ocean air joyfully and said how fine it would be to live in a comfortable snow house, away from buzzing flies and boiling hot sun, and that perpetual sense of work always awaiting them in the woods.

Frost made Kak feel like a war horse. He longed to have the flat ice under his feet again, with two dogs, perhaps three if he was lucky, harnessed to the sleigh, and run—run—run—abandoning himself to that glorious sense of space and motion which was his heritage.

The first person he hunted up at the cape was Kommana.

“Got that pup for me?” he shouted.

“Got that snow shovel?”

“Sure thing!”

Kak proudly produced their wonderful slab of spruce, and when everybody about had admired and praised it he was offered his choice of the six-months-old dogs.

The boys’ fathers were party to this trade, for a single piece of wood the width of the one they had brought was considered very valuable—worth almost as much as Taptuna’s new sled.

This was a large village, many Eskimos from the north and east had come to trade, and things took on the character if not the appearance of one of our small-town fairs. Besides their business the traders indulged in sports, jumping and racing and playing football. Their balls are made of soft leather sewed together in sections, much like ours, and are stuffed with caribou hair. The hair of the caribou, being hollow, is very buoyant; this is why the animals float nearly half out of water after they are killed. Their hollow hair is often used in manufacturing life preservers and is considered better than cork. Balls filled solidly with it bounce quite well, and the Eskimos have a lot of fun kicking them about. Kak was rather good at games, though, of course, he could not hold his own against men, but Kommana had no use for them.

“You’ll be old before you’re grown!” Taptuna jollied him. “Come and take a turn at this—just try.”

He sent the ball spinning with a good kick-off. Fatty watched but shook his head.

“Ah, leave him be, dad! He’s always tired,” Kak cried.

He sat down by his friend and was soon telling stories of their southern travels. Kommana wanted to hear all about Jimmie Muskrat, and Selby, and Noashak’s adventure with the deer. They talked till nearly dark, and when the younger boy got back to the tent he found his father and Okak in a friendly dispute concerning the best route home.

Taptuna’s idea was to go westward, striking across the mouth of the straits for Cape Baring, the southwest corner of Victoria Island, where they would have a very good chance of killing a few polar bears before the hardest frost set in, causing the open water to lie farther and farther offshore, and leaving them to their regular life on the ice catching seals. Okak as usual was raising objections. He still had a quantity of trade goods, and things from their spring cache made the load heavy. His neighbor pooh-poohed this, for they might count on smooth going; but Okak was not to be easily moved. He sat, brows knitted, a picture of worry, and tried to think up better objections. Guninana glanced at him once or twice with a merry twinkle in her eye. She knew his trouble—the poor chap was scared stiff about bear hunting. The woman guessed right, but at that she guessed only half his misery. Either way made Okak tremble in his shoes. For days and days recollection of his cold ducking, with renewed horror of snatching currents and bending ice, had been haunting his memory. He did not forget it would be safer farther west where the water flows more slowly—but what is the use of a safety leading straight into the jaws of nasty, snarling bears? He growled like a bear himself, seeing Taptuna wink at his wife.

In her heart of hearts Guninana sympathized with the nervous man. She would have been better pleased to settle down on the ice immediately, even if it meant eating seal and nothing but seal for months; and so she was highly delighted when Okak suddenly burst out:

“Two dogs are not sufficient! With only two men and two dogs the results will be as poor as the hunting is risky, and all our time wasted.”

Nobody answered this for it was sound reasoning. The little man sat back rubbing his knees with a that-settles-it sort of superior manner.

“Alunak might join us,” Taptuna muttered, annoyed.

“He has promised his wife to go to Franklin Bay and try to meet the Kabluna. She wants some steel needles.”

Guninana’s speech sounded gently satisfied; Okak observed it and swelled with importance.

“Two dogs——” he began, intending to enlarge on his happy inspiration, but it was just at this moment Kak entered.

“Who said ‘two dogs’?” the lively lad cried in a round, booming, out-of-doors voice. “What about Kanik—my pup? I’d have you remember we’ve got three dogs now!”

The resonant words shot like a boomerang through Okak’s self-complacence. Instantly he knew the cause lost. He heard it in Guninana’s little gasp; read it in his neighbor’s sparkling eyes bent on the intruder.

“You think of everything, my boy. I had forgotten Kanik.”

Taptuna spoke quietly, but all saw his elation. He felt immensely proud of Kak, and in that the boy’s mother must join him. Fresh proof of her son’s cleverness always put Guninana into beaming good humor; moreover, it is fun to play on the winning side. The family joined forces against Okak and silenced his arguments if not his fears.

They agreed to travel as far as Crocker River with Alunak’s party, and this journey turned out harder and slower than anybody had anticipated, for a strong wind from the northwest blew directly in their faces all the way. At the river Okak made a final throw for safety by trying to persuade their friends to join forces in bear hunting at the eleventh hour. Alunak himself was minded to do so, if it had not been for his wife’s fixed idea about needles. He had promised, and the lady being a very dominant person meant to see that he kept his promise. They all got into a great discussion over it, which lasted while they were house-building and eating, and commenced again the next morning. Nothing would turn the woman; Guninana even offered to lend her a needle for as long as they were in Victoria Island, but she held to her point. Perhaps she was as curious to see the Kabluna as to inspect his trade goods; Kak thought so anyway, and blazing with a wild hope suggested they might all go on to Franklin Bay first. When his father answered “No,” most emphatically, he grew tired of the merry argument and, deciding to take his dog for a walk, went out alone.

Kanik leaped up, pawing his master’s shoulders, making no end of a fuss and acting silly as a pup does; the pair were perfectly happy till Sapsuk got on to what was afoot and whined, wagging his tail, pleading to be allowed to go. In his present mood the boy thought two a company and three a crowd, so he felt annoyed. Sapsuk might be his favorite, but Kanik was his own—if you have ever possessed a dog you will understand. Kak was so torn between the two that in the end he took neither.

“You have to work hard, and it is better for you to rest,” he admonished like a grandfather, and started off, his walk already half spoiled. “If Sapsuk keeps this up I’ll never be able to teach the pup anything!” the boy muttered fretfully, for the first time wishing his friend had loved him a little less.

Conditions showed that the wind blowing against them all the way along must have been here a heavy, continuous gale. It had piled more ice into the western mouth of the straits than had ever been known before. The coast rose high. From its cliffs Kak beheld great masses of ice filling the whole expanse, rolling away billow on billow like a prairie country, goodness knew how deep under the trackless, gleaming snow.

“Jimminy!” thought the boy. “This old sea is going to take some crossing!”

He questioned if Omialik had started and felt a pang considering how near his hero might be at that minute and he unable to reach him. Then recollection of Okak brought a grin. “Our neighbor wanted it thick and he’s got it—perhaps he’ll be sorrier yet we didn’t travel by the eastern straits. I wonder what the going really is like out there?”

To think was to act with Kak. He immediately scrambled down the cliffs and a half hour later was walking alone over the corrugated ice field.

It was a shimmering sort of day. The sun struggled to penetrate the clouds, but did not quite emerge. The world lay trackless, formless, shadowless, a vast expanse of gray-white sky and gray-white snow. This kind of light is far harder on the eyes than bright sunshine, and since his snowblindness Kak had been very nervous about eyes. He kept his screwed up, not looking intently at anything, nor paying much attention to where he went, for he counted on the cliffs to guide him back. He only wanted to get a general impression of what their next march would be like and so strolled carelessly up a high ridge for a better view.

All at once Kak felt himself falling. He instantly thrust out his elbows so they would catch on the edges of the ice, for he knew what had happened. Stepping heedlessly he had walked on to the snow roof of a crevasse and had gone through into the crack. This is a common form of Arctic accident. The boy expected to stop when he had fallen as far at his waist, and to be able to hoist himself out, none the worse for his adventure; but to his surprise and horror he kept right on falling. The width of this chasm was so great that his elbows did not reach the walls. For an instant Kak felt helplessly angry—then the serious side broke on him. He was falling, falling—where to? On what would he strike—ice or water? How far would he fall? How hard would he strike? Sick with fear he tried to use his frenzied wits. It darted into his mind like a javelin that they would not know at home where he had gone, for snow so hard-driven by the gale was trackless as a rock. How he wished now he had taken either of the dogs, or both! He thought of Omialik, regretting Herschel Island, and in the middle of his keenest sorrow for the young marksman who would never be, both feet hit suddenly, smack on glare ice, flew from under him, and pitched him shoulder on against the solid wall. He slid down, smashing the back of his head, and lay still. Pain mingled with relief. It seemed for a moment as if nothing again could ever be so bad as that falling sensation. But the brief happiness passed. He realized he was lying captive between two high, hard, slippery sides, which towered above his head in twilight to the snow roof of the crevasse, offering no way out of that strange, cold prison. Above he could see the jagged hole he had torn in falling, and beyond it the gray sky. Through a fresh tide crack in the ice floor he saw water. Fear gripped him again when he thought how a little less frost would have allowed him to go right splash into it; for when an ice cake cracks it splits from top to bottom, leaving open ocean. Had the storm which roofed the tunnel over brought a spell of warm weather instead of cold, as storms often do, there would have been no floor formed in the crevasse. Bad as his plight was, things might have been infinitely worse. Suppose he had been floundering and freezing now—drowning, down in the bottom of that dismal jail without means of escape or alarm. Again, and this time in a very different mood, he regretted leaving his faithful dog. Sapsuk would have had sufficient intelligence to run and fetch Taptuna.

Kak knew very well nobody would come to help him, so he must help himself. As a beginning he took stock of his condition. One hip and shoulder were badly bruised and painful, and a goose egg was already developing on his head; but no bones seemed to be broken, nor could he find sprains or dislocations. So far so good. His first idea was to cut steps in the face of the ice wall and climb out. Putting his hand to his belt he found both knife and sheath had been torn away. “Still, it must be here,” the boy said bravely, and commenced looking around. The tide crack mocked him like an open, laughing mouth. “Foxes! If it has gone in there!” he cried, fumbling frantically under the snow which had showered down with his fall. Presently his fingers rapped on a horn handle. He made one grab and almost wept for joy. Just then his knife seemed his salvation; but five minutes later it had lost half of its value. On trial he found the sides were too far apart for him to support himself by a braced arm or knee as he climbed, and walking straight up a perpendicular, slippery surface by toe holes is an utter impossibility.

Kak now understood getting away was going to take all his invention and nerve and strength. The first step was to learn his surroundings. This crack might run smaller or lower at some other point. He set out exploring. It was an eerie sort of business to turn his back on the pool of light striking through the roof hole, and crawl over glare ice, between those blue-white walls, into the very heart of the stupendous jam he had so recently viewed with wonder from the cliffs. On hands and knees the boy began his strange and thrilling tour. His position brought him close to the floor, and once beyond the showered snow he saw tracks in the hoarfrost on the ice which made him flinch. He had company in the tunnel. The footsteps went both ways, as if some poor trapped creature had run to and fro, to and fro, in a crazy hunt for freedom. Kak knew very well what tracks these were. Acute dread shuddered over him. “But the crevasse may be long,” he comforted himself. “With luck I may get out before we meet.”

He crawled for thirty yards, stood up, and tried to guess the height of his prison. The snow roof looked thick and solid here, and though some light filtered through it, and doubtless a little through the ice itself, the gloom was sufficiently thick to confuse calculation. Space seemed to yawn above him; Kak felt rather than saw those walls were higher and wider apart; so he retreated to his first position and, only waiting to take one long look up at the friendly sky, set out in the opposite direction.

There was no question about it, the walls lowered toward this end. Fired with hope our boy scuttled along like a crab. The ice lay perfectly smooth, slippery as a ballroom floor. He crawled a few feet and stopped to glance above, and crawled on, and stopped, till familiarity made him careless. Very soon he was crawling and gazing upward together, forgetful of everything but his anxiety to climb out. Then suddenly the advanced arm plunged down splash into another tide crack. Kak uttered a yap of surprise, snatched back his hand, peeled off the wet mitt and dried his fingers quickly on his clothes. It had not gone in above the wrist, but a wet mitt was going to be less comfortable than a dry one; the captive felt vexed at his stupidity, blamed his position for it and scrambling to his feet walked slowly, steadying himself with his right arm against the wall, which bent at a gentle angle. Soon he spied ahead a second pool of light, a second scattering of snow from a hole in the ceiling. For an instant Kak felt glad—misery loves company—then it dawned on him what had fallen through, and his teeth chattered. This snow, packed and trodden down, looked several days old. Would he find a dead thing here entombed with him—or worse, a hungry living thing?

It took all the boy’s grit to make him go on. Only the sight of those lowering sides lent him courage. His sole chance for safety might lie hand in hand with this mysterious danger if the beast had elected to live in the small end of the crack. Light was failing again as he moved away from the second hole, and the darkness tortured his trembling nerves. Cautiously the lad stole on. His right hand grasped his knife, his left was ready for action; while he seemed to cling to the slippery path by his toes.

On either hand the sides sloped downward. “If it keeps on like this the crack will end in a cave,” Kak thought, “a cave with a top of soft snow well within my reach.”

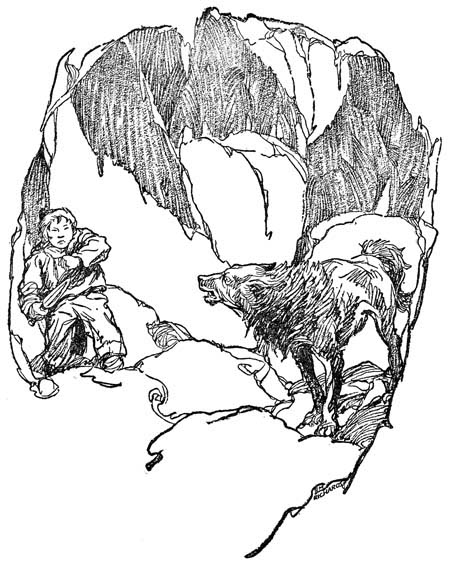

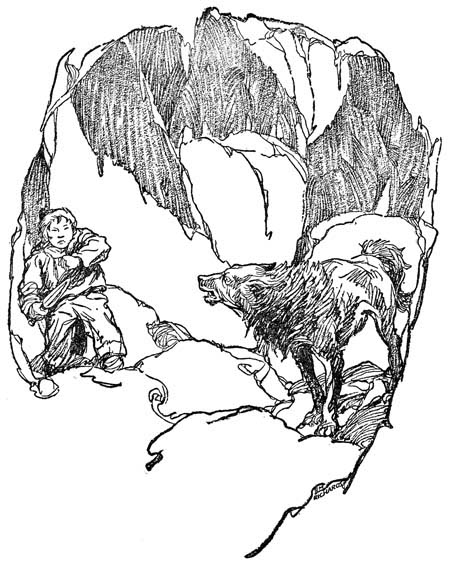

Sure enough! He came to another corner, rounded it timidly, and found himself facing the end of the tunnel where the walls ran sharply together, forming a narrow cave. In this cave, filling it completely, stood a full-grown wolf. Its gaunt, gray form was partly shrouded by gray gloom, but the yellow eyes looking out of that triangular face were horribly alive. Kak stopped, choking back fear. He swallowed. His breath caught and came in sobs, turn about. He wanted to fly and was too frightened; so he just stood like a fool, waiting for the famished animal to spring and devour him. The wolf waited also.... Little by little, as nothing happened, the boy regained his common sense. Of course the wolf would be scared, poor thing, cornered that way with no means of escape! He saw it was petrified by fear. It looked thin and hungry and was probably weak. Kak felt very sorry for his fellow prisoner, yet he wanted to put distance between them. One never knows the strength and wickedness of a wild animal at bay.

The two stood regarding each other, neither of them moving. Kak had the advantage—he could retreat. His brain worked madly.

“If I go back to the second hole,” he thought, “and try knocking some more snow down and piling it up against the side of the crevasse, possibly I can climb out there.”

Stealthily he edged away, keeping his eye on the foe till the curve of the wall divided them; then he made tracks as fast as he could over the glare ice.

Standing under the hole broken by the wolf’s fall Kak sent his knife flying up against the roof; it fell back amid a tiny shower of snow. He threw it again; a slightly heavier cloud descended. At each throw a little more seemed to come down. The boy was all eagerness; he tossed and tossed and tossed in a fury of excitement till he saw the precious knife suddenly shoot up against the sky. For one terrifying instant it looked as if it would fall outside on top of the crust. His heart stopped beating. He shut his eyes. Hours seemed to pass before the tinkle of copper on ice broke his tension.

“Bears and foxes! How could I have been so careless hopping about that way and never giving a thought!”

Facing a large, ravenous wolf with a knife in one’s hand, and facing the same beast unarmed are vastly different. This momentary shock made it clear to Kak he was fairly well off, but it jarred his faith in the new scheme. He was afraid now to throw with energy and abandon, and the roof seemed too hardly packed to be broken by half measures. He scraped the loose snow together with his feet, piled it up, patting it hard by hand, stood on it and tried to reach the top. But most of the mound had been lying on the ice floor and was all powdery cold so that it broke under his weight.

“This will take days!” the boy cried in despair. “I’ll be hungry and maybe freeze, or perhaps the others will give me up and go away.”

His fingers in the wet mitt felt bitterly cold. Taking it off he drew his hand through the loose sleeve of his coat and shirt and cuddled it against his warm body while he stood gazing at the height of those forbidding sides. All the time his glance rested on their inaccessibility his mind was busy reckoning how low they ran in the cave behind the wolf.

“I’ve got to do it! I’ve got to do it! I must get out of here before night,” wailed Kak. He turned and looked undaunted down the tunnel.

“I’ve just got to!”

Screwing his courage to the breaking point and grasping his knife more firmly the second prisoner crept forward to the angle in the wall. He shoved his head around cautiously. There stood the wolf exactly as Kak had left him. He seemed too frightened even to blink his eyes.

Quite aside from the fear of combat Kak was reluctant to attack this poor caged animal.

“If it only wasn’t so narrow there I could shove in and shove him out—given a chance he’d split past me like the wind.”

But it was narrow in the cave, much too narrow for any maneuver of that sort.

“I’ve got to kill him and haul him out! I haven’t any choice,” cried the boy.

KAK RUSHED FORWARD WITH HIS KNIFE READY.

Kak rushed forward with his knife ready and his left arm thrown up in front guarding his face. When the beast reared and hurled itself for a grasp of the enemy’s throat its long jaws closed on the shielding wrist. With a gasp of pain the boy flung his arm wide, wrenching the wolf’s head clear around, and at the same second stuck his blade deep into the side under its foreleg. Between the double shock of the twist and the blow his victim lost its footing and fell to the ground with a heavy crash, dragging the hunter down on top of him. For a moment Kak rolled amid a convulsed mass of feet and legs, then as the spasm ceased the vise grip on his arm relaxed, and the animal fell limp. Such narrow quarters had offered no chance for a fair fight; it was lunge, grab or be grabbed, and die.

The boy scrambled to his knees, withdrew his knife, dragged the warm body out of the way, and with a shudder sprang from it into the extreme end of the crevasse. For five minutes he worked off his emotion by hacking snow like a madman. It fell around and over him in showers, hiding the bloody trail that oozed across the ice and the spatters from his wounded wrist of which, in his haste to get away, he took no heed.

All at once the roof broke, came down like an avalanche, and the fresh air streamed in. The boy stopped for a deep breath. He could grasp the ice edge with his fingers, but it was still too high for him to pull himself out. He worked swiftly, cutting blocks from the ceiling and piling their fragments against the end of the crack; and all the time it seemed as if that hideous wolf behind was rearing over him, fixed-eyed and open-mouthed.

Kak was pretty tired and unstrung when finally he placed both hands on the crusted snow and drew himself into freedom. How good the air tasted. How heartening was the vast horizon sweep! He ran to warm up, for it had been searchingly cold down in the bottom of that deep ice pit. “Bhooo!” he shivered, nursing his sore arm. Running soon set the healthy blood coursing in his veins; his body tingled and his spirits rose.

As soon as his nerves grew normal Kak’s point of view changed. He saw the hair-raising experience might be turned into splendid adventure.

“Why not have some honor out of this?” the boy thought. So instead of dashing home all trembling and excited, he held himself down to a steady walk, stopped outside a minute to give old Sapsuk an apologetic little love pat, also for the sake of seeming casual, and then strode in.

“I’ve killed a wolf, dad,” he said. “It’s a thin, poor thing, but it will help. See here.” And he threw his bloody knife on the floor by way of evidence.

Guninana wasted no time on the weapon; one glance at his sleeve and mitt set her bustling around for rude means of relief. The others cried out in amazement, examined the knife, bombarded him with questions, laughed and clapped like children, quaked and marveled, while Kak wallowed in praise and the show of his mother’s attentions. Okak was for going after the carcass at once; but the hunter assured him the meat was safely cached, and burst into laughter at what he called a good joke—then he had to explain. Unable any longer to keep up his hero pose he told the whole story.

It was an amazing story. Such ice formations are more common in the Antarctic than the north. Everybody flocked over to see the crevasse and help bring the victim home. Taptuna skinned the wolf beautifully; and you may be sure the boy was very careful to pack his trophy next morning, when the parties separated, each going its own way with perfect understanding, and much calling of gay good-bys back and fore.

Our friends were in high spirits. No one really minded the difficulties of rolling ridges and heavy travel. Guninana gloried in her son; Kak was triumphant; Taptuna seemed as proud of his new sled as Noashak of her coat with red trimmings. And Okak had enough trade goods to make him a well-to-do man.

Their summer trip had prospered through strenuous labor and thrilling feats, and they all looked forward to their winter on the ice as a well-earned holiday.

END