APPENDIX.

A.—ON THE SPELLING OF WORDS AND NAMES.

IT will be noticed that the orthography of Indian words in the text differs with each writer, and this is the case in all the writings of the period. That phonetic method of spelling, which has passed into literature in the works of Thackeray and Macaulay, and for a return to which a writer in one of the magazines recently entered a plea, reigned supreme, but with this drawback, that each man expressed differently the sounds he heard. To take one instance, the comparatively simple name Baj-baj appears in various writings as Buz-buzia, Buz-budgee, Busbudgia, Budje Boodjee, and Bougee Bougee, besides the more modern Budge-Budge. The first person that rendered Murshidabad as Muxidavad evidently pronounced the x in the Portuguese way, as sh, when the name is quite recognisable if the accent be placed on the first syllable, but those who followed him, ignorant of this fact, passed from Muxadavad into Mucksadabad—a terrible example of the dangers of a follow-my-leader policy. Some writers, and notably Holwell, made an effort to obtain uniformity. Aghast at discovering the long a sound (as in Khan) variously rendered by o, u, au, and aw, they employed aa for the purpose, and hence we are confronted with such monstrosities as Rhaajepoot for Rajput. Considering the difficulty of rendering Hindustani words by means of English letters, the modern student may be thankful for the Hunterian system, which at least ensures uniformity, even though upon a purely conventional basis. It may be mentioned that the diversity is not confined to Indian words. The name of le Beaume is spelt in four different ways.

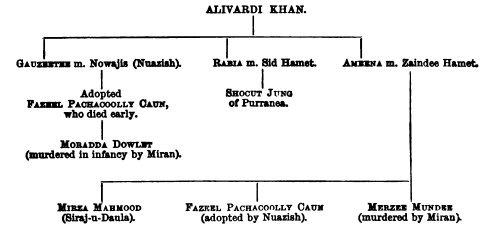

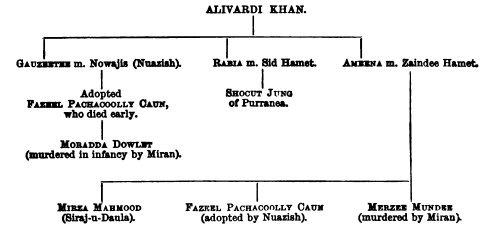

B.—THE FAMILY OF ALIVARDI KHAN.

The following table has been compiled from Orme’s History and the Seïr-ul-Mutaqharin to show the relationship of Alivardi Khan’s descendants. The three daughters of Alivardi married the three sons of his brother Hodjee Hamet (Haji Ahmad), while his half-sister Shah-Khanum was married to Mir Jafar, and became the mother of his son Miran.

C.—AUTHORITIES FOLLOWED IN THE TEXT.

The period treated in this book is singularly rich in contemporary personal records. Holwell, Watts, and Scrafton have left us lengthy narratives of their experiences, and Ives, Admiral Watson’s surgeon and clerk, supplies a detailed account of the campaign of vengeance which terminated at Plassey. Clive’s letters give us the military point of view, and in the Seïr-ul-Mutaqharin we have that of the natives. Orme’s History (1763) appears to have been compiled from other documents still, probably the official letters addressed to the Court of Directors, since his account of Mr Watts’ escape from Madhupur, for instance, is far more detailed than that contained in Watts’ own ‘Memoirs of the Revolution in Bengal.’ Orme’s account is followed in the text, save that other names have been substituted for those of Messrs Collet and Sykes and Dr Forth, whom the historian mentions as Watts’ companions in addition to the Tartar servant. The evidence given before the Parliamentary Committee of 1772 adds many interesting details, and the same may be said of two MSS. in the Hastings Collection, one written by the anonymous junior civilian who is called Mr Dash in the text, the other the apologia of Captain Grant, who had fought under Prince Charles Edward at Culloden, and succeeded, when the Jacobite cause was lost, in escaping to Bengal, where ill-fortune still pursued him. I am indebted to Dr Busteed, whose book, ‘Echoes from Old Bengal,’ is a mine of curious information on eighteenth-century Calcutta, for directing my attention to these writings. The description of Siraj-u-Daula’s Durbar is taken from the Discours Préliminaire of Anquetil du Perron’s translation of the ‘Zend-Avesta,’ the French traveller having visited Murshidabad during the prince’s short reign. For various minor details, the ‘Voyages’ of Grose and of Mrs Kindersley have been laid under contribution, while Broome’s ‘History of the Bengal Army’ has afforded a standard by which to compare the often varying contemporary authorities.

The variations and discrepancies in these narratives form indeed the great difficulty of the historian, and with these must be joined their omissions, particularly in matters of date. Thus there are no means of knowing the exact time at which Mr Watts’ letter of warning as to the Nawab’s intentions arrived, or when the Delawar entered the Hugli with the instructions of the Court of Directors, when Siraj-u-Daula was formally proclaimed in Calcutta and the Governor’s letter of congratulation forwarded, or when “Fuckeer Tongar” and the Nawab’s second messenger arrived, or lastly, when the “first prohibition of provisions” took place, at which time Holwell recommended the seizure of Tanna. I have endeavoured in the text to place these events in their probable order and in a right relation to one another.

D.—THE HISTORICAL PERSONAGES INTRODUCED.

In consequence of the abundant information obtainable, there is little scope for imagination in the treatment of the historical personages brought into the story as secondary characters. Messrs Holwell, Eyre, Bellamy (father and son), Mapletoft, le Beaume, Watts, and Hastings, and Governor Drake and his two friends, stand revealed either in their own writings or those of their contemporaries. The characters of the five captains commanding the Calcutta forces are drawn for us by Holwell, but students of the original narrative will observe that I have substituted the name of Captain Colquhoun for that of Buchanan. So also the brilliant young civilian who survived the Black Hole to become Clive’s instrument in the matter of the false treaty is called in the text by the name of Fisherton. It may be objected that the character of Drake and his fellow deserters is drawn too exclusively from the records of those who suffered by their cowardice in forsaking Fort William, but to that I may reply that neither Grant in his MS. defence, nor Manningham in his evidence before the House of Commons Committee, succeeds in shedding any more agreeable light on the disgraceful exploit, while Drake’s opinion of the affair is shown by his having, in conjunction with the Council, sentenced Captains Grant and Minchin to be dismissed the Service, for following his own example. Grant, it may be remarked, was afterwards reinstated, in view of his unsuccessful efforts to induce the President to return to the help of those left in the Fort, and he took part in the hostilities which culminated at Plassey.

Admiral Watson’s character is described in detail by Ives, and sketched at some length by Watts, while the chance allusions of other writers concur in assuring us of his extreme amiability as a man, and his high qualities as a commander. (His tomb, like that of young William Speke, is still to be seen at the Old Cathedral, Calcutta, and it may be news to some Londoners to learn that there is a monument to him in the north transept of Westminster Abbey.) The remarkable indecision displayed by Clive before the engagement at Plassey is historical, and appears to have been due to one of those fits of depression to which he was subject. The name of Sinzaun will not be found in the records of the period, but we learn from Grant that the Nawab’s artillery at the siege of Fort William was under the command of a French renegade, who called himself the Marquis de St Jacques, while the last stand at Plassey was made by a small company of French under a leader called St Frais, whose name was spelt Sinfray by the English and the natives, and who was not killed, as is erroneously stated in the index to Malleson’s ‘Life of Clive,’ but lived to fight another day.

E.—THE TOPOGRAPHY OF CALCUTTA.

One of the chief difficulties in tracing the various localities of old Calcutta is the extent to which the river-bank has altered its shape and position, so that where in Orme’s day was water, there are now streets and squares. It is still possible, however, to discover some of the old land-marks, although the Fort William of the text must not be sought for on the site of the present one, for that was built by Clive where the hamlet of Gobindpur had formerly stood. The Post Office marks the spot occupied by the original Fort William, and the site of the Black Hole (the discovery of which in 1883 is recorded by Dr Busteed) is marked by a stone bearing an inscription. The Park or Lal Bagh is the present Tank Square or Dalhousie Square. The site of the church is thought by some to be occupied by St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church, while the Old Cathedral (St John’s) marks the site of the burying-ground mentioned in the text. The present Government House covers, so far as can be determined, the site of the old Company’s House. The gaol, says Broome in 1850, “was about the site of the present Lall Bazar Auction Mart.” The present suburb of Hastings stands on the site of Surmans, and the ground between it and the city proper, now occupied by Chauringhi and the Maidan, was still a marshy jungle even at the end of the last century. The Chitpur Road, an old native pilgrim-way, marked the division between the English and native quarters of the town, and the Marhata Ditch followed the course of the present Circular Road. Further information on this interesting subject may be obtained from Dr Busteed’s book and Sir William Hunter’s ‘Gazetteer of India,’ art. “Calcutta.”

F.—SOME POINTS IN CONNECTION WITH THE FALL OF CALCUTTA.

It is difficult to resist the conclusion that never was a city more thoroughly warned of its impending doom than the Calcutta of 1756, and the fact renders the alternate defiance and cowardice of the Presidency the more unaccountable. That the actual approach of peril took them altogether by surprise appears certain, and Orme blames Mr Watts for not informing them until the danger was close at hand of the anxiety as to their intentions displayed by Alivardi Khan in his death-bed conversation with Dr Forth, which appears to have been considered by Siraj-u-Daula as a justification for his own subsequent proceedings. But without adopting the extreme view of the French, that the siege and its consequences were the outcome of a deliberate plan formed by Drake and his confederates for the destruction of Holwell, there can be little doubt that the President and his two friends were playing a double game, and found themselves defeated only because they met with opponents still less scrupulous than they were. The constitution of the Council was such as to render it extremely easy for them to manipulate public affairs in their own interest. Watts, the accomptant and second in command, was absent at Kasimbazar, and the executive was practically in the hands of the Governor, Manningham the warehouse-keeper, and his “partner” Frankland. The House of Commons Report makes it clear that these three were suspected not only of supporting the claims of Ghasiti Bigam against those of Siraj-u-Daula in the hope of gain, but of accepting a money bribe to allow the admission of Kishen Das into Calcutta. The writer who in the text is called Mr Dash goes further, and asserts roundly that their earlier defiance of the Nawab was intended to alarm the protected merchants and wealthy men of the surrounding districts, and induce them to seek refuge in Calcutta, when the Presidency might levy blackmail on their possessions. After this we are scarcely surprised to learn on the same authority that Drake and his friends were wont to apply to their own use as much as 10,000 rupees a month, which was a part of the sum devoted by the Court of Directors to the payment of the army—an army practically non-existent—nor that the plunder found at Tanna was put on board the Doddalay, the ship which belonged to the three confederates, and transferred to the snow Neptune. Having attained their object in despatching the expedition, the Presidency had no further interest in Tanna, but kept up a show of activity without any real result on the second day, merely in order to cover the passage of the Neptune up to Calcutta. It is some consolation to hear that when Fort William was abandoned, this vessel went ashore near Baj-baj, and the treasure was lost.

Unfortunately for the plans of the Presidency, it can scarcely be doubted that they were overreached from the first. The hollowness of the Nawab’s anger against Kishen Das, evidenced not only by the honours showered upon him on the fall of Calcutta, but by the fact that Rajballab, the father, and presumably the more guilty of the two, remained unmolested at the Court from beginning to end of the matter, seems to show that the affair of Kishen Das was nothing but a ruse, intended to bring about the ruin of the English by arousing their cupidity. That it was devised by Amin Chand and his friend Gobind Ram Mitar, as was suspected at the time, in revenge for what they considered the injustice with which they had been treated, is scarcely more doubtful. The double-dyed traitor Amin Chand appears, indeed, to have played both parties false with the greatest impartiality throughout his career, but the special malevolence displayed towards Holwell and the three others by whom he conceived himself to have been particularly injured seems to prove that the overthrow was plotted by him, and this is corroborated by the correspondence discovered between Amin Chand and Manak Chand. In consequence of this unsuspected treachery, the President and his friends, who had counted confidently upon the defeat of the Nawab, first at the hands of Ghasiti Bigam and then at those of his cousin of Parnia, found their confidence futile, and the airy carelessness with which they had been wont to discuss affairs of state, both with casual acquaintances and with the natives, contributed to their downfall by the information it furnished to the enemy. It is interesting to observe that in his examination before the Commons Committee, Manningham observes with the greatest coolness that in his opinion it was not in the power of any man to give a reason for the disaster, and that he knew of no conduct on the part of the Company’s servants likely to incense the country government. In regard to their intentions, this is probably true, but it is almost impossible not to believe that their plans for their own aggrandisement recoiled upon them in a way they little expected.

The conduct of the Governor and his friends during the siege appears to have been due merely to pusillanimity, for even Mr “Dash” does not venture to hint at treachery on their part. The incapacity of the engineers prepared a position impossible of defence, and the cowardice of those in command precipitated a defeat which a more resolute resistance might have delayed, and thus averted altogether. The flight of Manningham and Frankland was a natural corollary to the abandonment of the north and south batteries, and the order to the captain of the Doddalay to drop down the river followed easily. In the text I have followed Captain Grant’s account of Drake’s flight, his own share in which he endeavours to excuse by asserting that the boat in which he accompanied him was the only one left. If this is true, it seems scarcely necessary to have locked the Fort gate to prevent further desertions, as we learn was done, and that others succeeded in getting away is probable from the narrative of Mr “Dash,” which ends with a suspicious abruptness after describing the President’s escape. Unless the anonymous writer was the Mr Lewis who accompanied Mr Pearkes to the Prince George, and was presumably saved with her crew, he must have found some means of reaching the ships from the Fort, for we know on his own testimony that he was among the refugees at Falta. Le Beaume, who is branded by Broome with the stigma of taking part in the stampede, is shown by Grant’s narrative to have been wounded, and by Holwell’s to have been sent on board the Diligence on the night of the 18th with Mrs Drake and the three other ladies who had been left behind. I have no authority for identifying these ladies (whose vessel was captured by the enemy off Baj-Baj, and all Holwell’s property lost) with those mentioned in the Seïr-ul-Mutaqharin as having fallen into the hands of Mir Jafar, and been by him restored to their husbands, but the identification appears probable.

[The End]