(XX)

(XX)

OH! our winter’s evenings of that time! In the most sheltered corner of the mansion, elsewhere closed and left silent and dark, was a small and warm parlor facing the sun, the courtyard, and the gardens, where my mother and Aunt Clara sat beneath their hanging lamp, in their usual places where so many past and similar winters had found them. And, usually, I was there also, that I might not lose an hour of their presence on earth and of my days at home near them. On the other side of the mansion, far from us, I abandoned my study, leaving it dark and fireless[62] that I might simply pass my evenings in their dear company, within the cosy room, innermost sanctuary of our family life, the home dearest to us all. (No other spot has given me a fuller, a sweeter impression of a nest; nowhere have I warmed myself with more tranquil melancholy than before the blaze in its small fireplace.) The windows, whose blinds were never closed, so confident were we in our security, the glass door, almost too summer-like, opened upon the desolation of naked trees and vines, brown leaves, and despoiled trellises often silvered by pale moonlight. Not a sound reached us from the street, which was some rods distant,—and besides a very quiet one, its silence rarely broken save by the songs of sailors celebrating, at long intervals, their safe returns. No, we had rather the sounds of the country, whose nearness was felt beyond the gardens and old ramparts of the city;—in summer, immense concerts of frogs in[63] the marshes which surrounded us smooth as steppes, and the intermittent flutelike note of the owl; in the winter evenings of which I write, the shrill cry of the marsh bird, and above all, the long wail of the west wind coming from the sea.

Upon the round table, covered with a gayly flowered cloth, which I have known all my life, my mother and aunt Clara placed their workbaskets, containing articles that I would fain designate “fondamentales,” if I dared employ that word which, in the present instance, will signify nothing save to myself; those trifles, now sacred relics, which hold in my eyes, in my memory, in my life, a supreme importance: embroidery scissors, heirlooms in the family, lent me rarely when a child, with manifold charges to carefulness, that I might amuse myself with paper cutting; winders for thread, in rare colonial woods, brought long years ago from over the oceans by sailors, and giving material for deep reveries; needlecases, thimbles, spectacles, and pocketbooks. How well I know and love every one of them, the trifles so precious, spread out every evening for so many years on the gay old tablecloth, by the hands of my mother and Aunt Clara; after each distant voyage with what tenderness I see them again and bid them my good-day of return! In writing of them I have used the word “fondamentale,” so inappropriate I confess, but can only explain it thus: if they were destroyed, if they ceased to appear in their unchanged positions, I should feel as if I had taken a long step nearer the annihilation of my being, towards dust and oblivion.

And when they shall be gone, my mother and Aunt Clara, it seems to me that these precious little objects, religiously treasured after their departure, will recall their presence, will perhaps prolong their stay in our midst.

The cats, naturally, remained usually in our common room,—sleeping together, a warm, soft ball, upon some taboret or cushioned chair, the nearest to the fire. And their sudden awakenings, their musings, their droll ways, cheered our somewhat monotonous evenings.

Once it was Pussy White who, seized by a desire to be in our closer company, leaped upon the table and sat gravely down upon the sewing work of Aunt Clara, turning her back upon her mistress, after unceremoniously sweeping her plumy tail over her face; afterwards remaining there, obstinately indiscreet, and gazing abstractedly at the flame of the lamp. Once in a night of tingling frost, so excitable to a cat’s nerves, we heard, in a near garden, an animated discussion: “Miaou! Miaraouraou!” Then from the mute fur ball, which slumbered so soundly, upsprang two heads, two pair of shining eyes. Again: “Miaraou! Miaraou!” The quarrel goes on! The Angora rose up resolutely, her fur bristling in anger, and ran from door to door, seeking an exit as if called outside by some imperative duty of great importance: “No, no, Pussy,” said Aunt Clara, “believe me, there is no necessity for your interference; they will settle their quarrel without your help!” And the Chinese, on the contrary, always calm and averse to perilous adventure, contented herself by glancing at me with a knowing air, evidently regarding her friend’s movements as ridiculous, and asking me, “Am I not right in keeping away from this fracas?”

A certain beatitude, profound and almost infantile, pervaded the silent little parlor where my mother and Aunt Clara sat at work. And if by turns I remembered, with a dull heart-throb, having possessed an oriental soul, an African soul, and a number of other souls, of having indulged, under divers suns, in numberless fantasies and dreams, all that appeared to me as far distant and forever finished. And this roving past led me more thoroughly to enjoy the present hour, the side-scene in this interlude of my life, which is so unknown, so unsuspected, which would astonish many people, and perhaps make them smile. In all sincerity of purpose, I said to myself that nothing could again take me from my home, that nothing could be so precious as the peace of dwelling there, and finding again part of my first soul; to feel around me, in this nest of my infancy, I know not what benignant protection against worthlessness and death; to picture to myself through the window, in all the obscurity of dying foliage, beneath the winter moon, this courtyard which once held my entire world, which has remained the same all these years past, with its vines, its mimic rocks, its old walls, and which may perhaps resume its importance in my eyes, its former greatness, and repeople itself with the same dreams. Above all, I resolved that nothing in the wide world was worth the gentle bliss of watching mother and Aunt Clara sewing at the round table, bending toward the bright flowered cloth their caps of black lace, their coils of silvery hair.

Oh! one evening I will recall. There was a scene, a drama among the cats! Even now I cannot recall it without laughter.

It was a frosty night about Christmas time. In the deep silence we had heard passing above the roofs, through cold and cloudless skies, a flock of wild geese, emigrating to other climates: a sound of harsh voices, very numerous, wailing not too harmoniously together and soon lost in the infinite regions of the sky. “Do you hear? Do you hear?” said Aunt Clara with a slight smile and an anxious look to banter me; recalling the fact that in my childhood I was greatly alarmed by these nocturnal flights of birds. To hear their voices one should have a keen ear and listen in an otherwise silent place.

Our room then resumed its calm,—a calm so profound that I heard the complaint of the blazing wood on the hearth, and the regular breathing of our cats seated in the chimney corner.

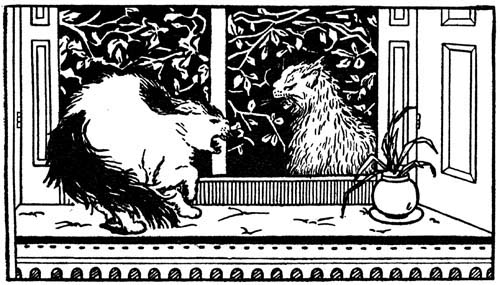

Suddenly, a certain large yellow gentleman cat, held in horror by Pussy White, but persistently pursuing her with his declarations, appeared behind a window pane, showing in full relief against the background of dark foliage, looking at her with an impertinent and excited air and uttering a formidable “Miaou” of provocation. Then she sprang up at the window like a panther, or a ball deftly thrown, and there, nose to nose, on each side of the pane, there was a useless battle, a volley of unpardonable insults poured out in shrill, coarse tones; blows of unsheathed claws given with emphasis, vain scratchings across the glass, which made great noise and did nothing. Oh! the fright of my mother and Aunt Clara, starting from their chairs at the first alarm,—then their hearty laugh afterward, the ridiculousness of all this impetuous racket breaking in upon the intense silence,—and above all the visage of the visitor, the yellow cat, discomfited and breathless, whose eyes blazed so drolly behind the glass!

“Putting the pussies to bed” was in those evenings, one of the important events,—“primordiales” shall I call it?—of our daily existence. They were never allowed, as are many other cats, to roam all night among the vines and flowers, beneath the stars, or contemplating the moon; we held opinions upon that subject from which we never departed and made no compromises.

“THERE WAS A USELESS BATTLE”

The going to bed was merely shutting them up in an old granary at the end of the courtyard, almost hidden under a growth of vines and honeysuckles; it was really in Sylvester’s quarters, beside his chamber; so that every evening they said good-night together, the cats and he. When each one of these days—these unappreciated days now wept for—was ended, fallen in the abyss of time, Sylvester was called and my mother would say in a half solemn tone, as if fulfilling a religious duty, “Sylvester, it is time for the cats to go to bed.”

At the first words of this phrase, uttered in ever so low a voice, Pussy White pricked up her ears; then knowing there was no mistake about it, jumped down from her cushion with an important though disturbed air, and ran to the door, that she might make her exit first, and on her own feet, unwilling to be carried, and determined to go of her own free will or not at all. The Chinese, on the contrary, endeavored to delay the inevitable change; reluctant to quit the warm room, she got down slyly, crouching very low on the carpet to be less in view, and glancing around to ascertain if any one had seen her, would hide under some article of furniture. The big Sylvester, accustomed to these subterfuges, called with his childlike tone and smile: “Where are you, Pussy Gray? I know you are not far off.” Tenderly she responded “Trr! Trr! Trr!” knowing further pretense useless, and allowing herself to be lifted to the broad shoulder of her friend. The procession finally took up the line of march: at the head, Pussy White, independent and superb; behind followed Sylvester who said “Good-night,” and who in one hand carried his lantern, and with the other grasped the long tail of Pussy Gray which hung pendent on his breast. The Angora usually proceeded resignedly to her proper sleeping place. Sometimes it happened, at certain phases of the moon, that vagabond fancies seized her, aspirations to play the truant and sleep at the angle of some roof, or at the summit of a solitary pear tree, in the bracing air of December, after having passed the entire day in an armchair by the fireside. On these occasions Sylvester soon reappeared with a drolly despondent face, still holding the tail of Pussy Gray who clung close to his neck: saying “Again that Pussy White will not go to bed!”—“Again! Ah! what actions!” replied Aunt Clara indignantly. And she stepped outside, herself, to try the effect of her authority, calling “Pussy, Pussy” in her dear, feeble voice which I can hear now, as it echoed then in the courtyard through the sonorous depth of the winter night. But no, Pussy obeyed not; from the height of a tree, from the top of a wall she gazed about her with a nonchalant air, seated at her ease on her chosen throne, her furry robe making a white spot in the darkness and her eyes emitting tiny phosphorescent gleams. “Pussy, Pussy! Oh you naughty creature! It is shameful, miss, such conduct, shameful!”

Then out in her turn came my mother, shivering in the cold, and trying to make Aunt Clara come in. An instant after, I follow to bring both indoors. And then to see ourselves gathered in the courtyard, in a freezing night, Sylvester also of the group and still holding his cat by the tail, and all this united authority set at defiance by a little cat perched high above us, gave an irresistible desire to laugh at ourselves, beginning with Aunt Clara, and in which we all joined. I have never believed there existed in the entire world two such blessed old ladies,—Oh! how old, alas!—capable of such hearty laughter with the young; knowing so well how to be amiable, how to be gay. Truly I have been happier with them than with any or all others; they always discovered in seemingly insignificant trifles an amusing or comical aspect. Pussy White decidedly had the best of the discussion! We reëntered, crestfallen and chilled, the little room too much cooled by the opened door, to gain our respective chambers by a series of stairways and sombre passages. And Aunt Clara, with a relapse of anger, when reaching her threshold, said to me, “Good-night; but, on the whole, what is your opinion of that cat?”