(XXI)

(XXI)

THE life of a cat may extend over a period of twelve to fifteen years, if no accident occurs.

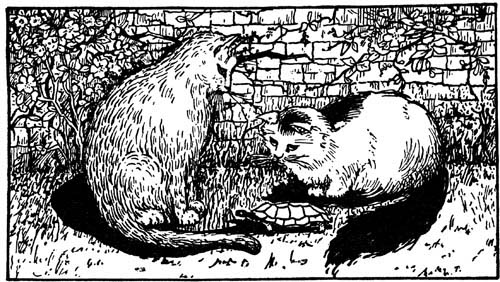

“IN COMPANY OF THE EVERLASTING TORTOISE”

Our two pets lived to enjoy together the light and warmth of another delicious summer; they found again their days of blissful idleness, in company of the everlasting tortoise, Suleïma, whom the years forgot, between the blooming cacti, on the sun-heated pavements,—or stretched on the old wall amidst the profusion of jasmines and roses. They had many kittens, raised with tender care and afterward advantageously domiciled in the neighborhood; those of the Chinese were in great demand, being of a peculiar color and bearing distinctive race marks.

They lived another winter and recommenced their long naps in the chimney corner, their meditations before the changing aspect of the flame or embers of our wood fire.

But this was their last season of health and joy, and soon after, their decline began. In the succeeding spring some mysterious malady attacked their little bodies, which should have endured vigorous and sound for still some years.

Pussy Chinese, first attacked, seemed stricken by some mental trouble, a sombre melancholy,—regrets perhaps for her native Mongolia. Refusing both food and drink, she made long retreats to the wall top, lying there motionless for entire days; replying only to our appeals by a sorrowful glance and plaintive “Meaou.”

The Angora also, from the first warm days, began to languish, and by April both were really ill.

Doctors, called in consultation, gravely prescribed absurd medicines and impossible treatments. For one, pills morning and evening and poultices applied to the belly! For the other, a hydropathic course, close shaving of the body, and a cold plunge bath twice daily! Sylvester himself, who adored the pussies, who obeyed him as they would no one else, declared all this impossible. We then tried the efficacy of domestic remedies; the mothers Michel were summoned, but their simple prescriptions were of no avail.

They were going from us, our beloved and cherished pets, filling our hearts with great compassion,—and neither the loveliness of spring nor its glory of returning sunshine could rouse them from the torpor of approaching death.

One morning as I arrived from a trip to Paris, Sylvester, while receiving my valise, said to me sadly, “Sir, the Chinese is dead.”

She had disappeared for three days, she so orderly, so domestic, who never left our premises. Doubtless, feeling her end near, she had fled, obedient to an impulse or sentiment of extreme modesty which leads some animals to hide themselves to die. “She remained all the week,” said Sylvester, “up on the high wall lying on the red jasmine vine, and would not come down to eat or drink; but she always answered when we spoke to her, in such a little feeble voice!”

Where then had she gone, poor Pussy Gray, to meet the terrible hour? Perhaps, in her ignorance of the world, to some strange house, where she was not allowed to die in peace, but was tormented, driven out,—and afterwards cast on the dunghill. Truly, I would have chosen that she might die at her home; my heart swelled a little at the remembrance of her strange human glances, so beseeching, so indicative of that need of affection which she could not otherwise express, seeking my own eyes with mute interrogation forever unutterable.—Who knows what mysterious agonies rend the little, disturbed souls of the lower animals in their dying hours?