CHAPTER X

JACK started for Texas as planned. He proposed going first to Fredericksburgh and thence to Squaw Creek where resided George Nelson, a Texas cattle king, to whom Jack carried a letter of introduction from Andrew Genung.

Nothing of special interest occurred to break the monotony of his journey until reaching Austin, where he intended to remain and rest a few days before continuing on by stage for Fredericksburgh.

Mentally and physically tired, he sought his hotel. What was life worth? Only too well did he know the meaning of this hectic flush. The events that had happened at his home had fallen like a pall over his hopeful nature, and though convinced that this change could do no more than prolong his life, he had undertaken it to please his mother.

At the hotel where he stopped was a young fellow by the name of Sevier, from Louisiana. He was having his eyes treated by Dr. Saugree, the most eminent oculist in Texas, and a bond of common sympathy drew the young men together. Mutual introductions followed and they became friends.

The second day after his arrival Jack felt much better and Sevier proposed that they visit the Capitol. Jack readily agreed and they were strolling leisurely in that direction when Sevier called his attention to a man on the other side of the street. He was clad in a hickory shirt, coarse baggy trousers, a broad-brimmed felt hat and brogans.

“A cowboy, I presume,” said Jack.

“What I first thought,” Sevier answered dryly. “He is president of the most solid bank in this city. Let me introduce you,” crossing over and bidding Jack follow.

“What are you giving me!” said Jack, thinking it a practical joke.

His new acquaintance was Timothy or “Tim” Watson, who shook hands warmly with Jack and when he heard the name De Vere, he said: “I must introduce you to one of your kin; am on my way to the bank now, but if you’ll go along I’ll attend to some necessary matters there and then take you to her house which is on the same street. From New York, are you? I reckon you don’t know a man there by the name of Andrew Genung?”

Jack’s face beamed with pleasure as he explained how very well indeed he knew him.

“Where did you meet him?” he asked Watson in some surprise.

“In Nevada and Californy, and many’s the jolly good ride we had together behind Hank Monk in the good old staging days,” replied Watson, his face aglow at the pleasure of the memory. But they were now at the bank, and bidding them be seated, he disappeared into an inner office.

Jack mentally contrasted him with the other bank presidents of his acquaintance and unconsciously laughed aloud.

Sevier, as if divining the cause, said—“There is not in the State of Texas a man possessed of more good, sound horse-sense than Tim Watson, nor a more honest financier.”

“I believe it,” Jack answered.

The subject of their discussion then appeared with the announcement that he was ready, and they soon arrived at the home of Miss De Vere, the aforementioned kinswoman of Jack.

Like most of the residences of the better class, it was built of native stone with a broad piazza, or “gallery,” extending around three sides of the house. Miss De Vere was busily engaged in her flower garden when Watson espied her, and in a stentorian voice called out,—“Howdy, Miss De Vere!”

Miss De Vere was apparently about sixty years of age, and as she graciously welcomed them, Jack was struck with the resemblance to his father’s family. Evidently she, too, saw the De Vere characteristics in Jack, for laying her hands on his shoulders she said meditatively,—“Strange the tenacity of race. Our type is a particularly strong one and distinctly perpetuated. John, too, is a name we cling to. All the De Veres in this country came from one common stock, and we need not be ashamed of one of our kin.”

“How about the one up last month for horse-stealing!” said Watson with a sly wink at Jack. But apparently his question was unheard and she ushered them into a wide hall extending entirely through the house.

She noticed sadly another trait in Jack, the tendency to pulmonary trouble, and her heart warmed toward this newly found kinsman.

Jack, too, felt greatly drawn towards her and was unconsciously led to talk about himself, his object in leaving home and his family. She earnestly pressed him to make his home with her during his stay in Austin, but as it would now be short and his belongings were at the hotel, he gratefully declined, promising to do so on his way home. His intentions were to take the next day’s stage for Fredericksburgh, so, after a most enjoyable time with Miss De Vere, they left. Jack’s heart was very tender as he received her good wishes and good-bye. “Truly,” he thought, “this world is very small,” and, turning, caught Watson eyeing him keenly.

“So you knew Andrew Genung?” he said, divining the latter’s glance of sympathy.

“You bet I did, and I’ll be doggoned if it don’t make me homesick to think of them good old days in the Rockies!”

“Did you know his brother?”

“Right well. What a good-for-nothing, unlucky devil he was. It aint good policy to marry among them Greasers. I’ve clean lost sight o’ their boy. Reckon he’s dead. I’m looking for a man by the name of ‘Bruce,’ in Virginia City, though God Almighty knows if he had a right to the title. He was a slicker, and buncoed Fred Genung along with myself. I’m ’biding my time, and if ever again I set eyes on him, one of us is goin’ to glory ’cross-lots!”

“But that is a long time ago, and he may either be dead or greatly changed,” returned Jack.

“Well,” replied Watson, “it is a good many years ago since he run that Faro Bank in Virginia City, and I reckon he is changed; but unless he’s got a bran-new face, I’d know him in Africa. Look-a-here, young man, no one can ever say that Tim Watson cheated him out of one cent, and this miserable hound is the only critter that ever got the best of Tim Watson. I’ll give him a chance to settle and if he don’t—” Here Watson’s face became purple and Jack hastily changed the subject.

Tim Watson was a character. His rules of business were inflexible in their honesty and his character bore the closest scrutiny. Men, women and children carried their troubles to him and his sympathies were always with the weaker side. His observant eye discovered something besides broken health in Jack’s face and he determined to keep an eye on the young fellow with the sad eyes.

Arriving at the bank, the young men left Watson there after obtaining a promise from him that he would spend the evening with them at the hotel, which they reached just in time for dinner.

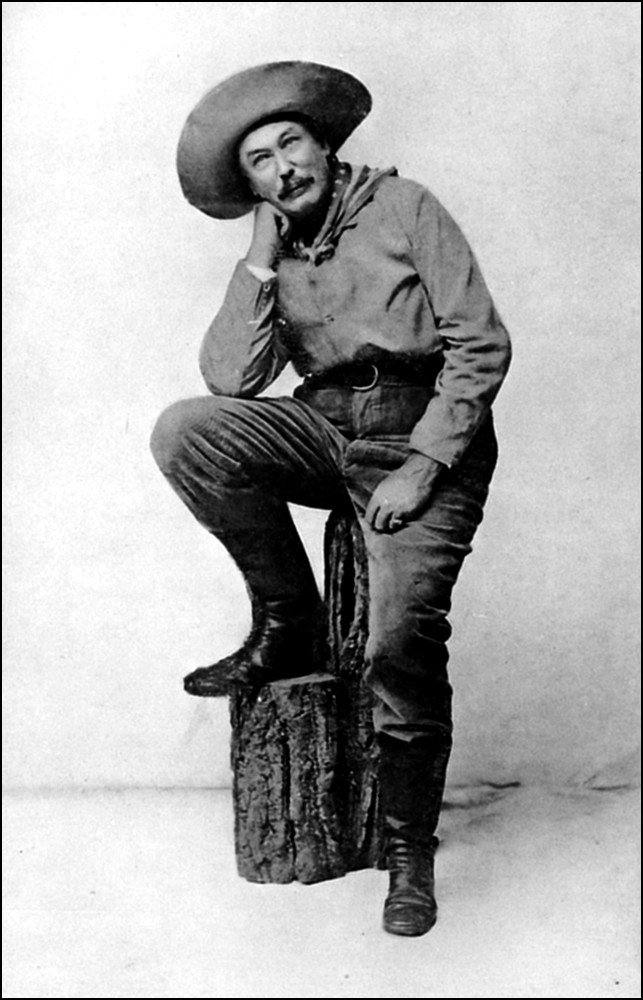

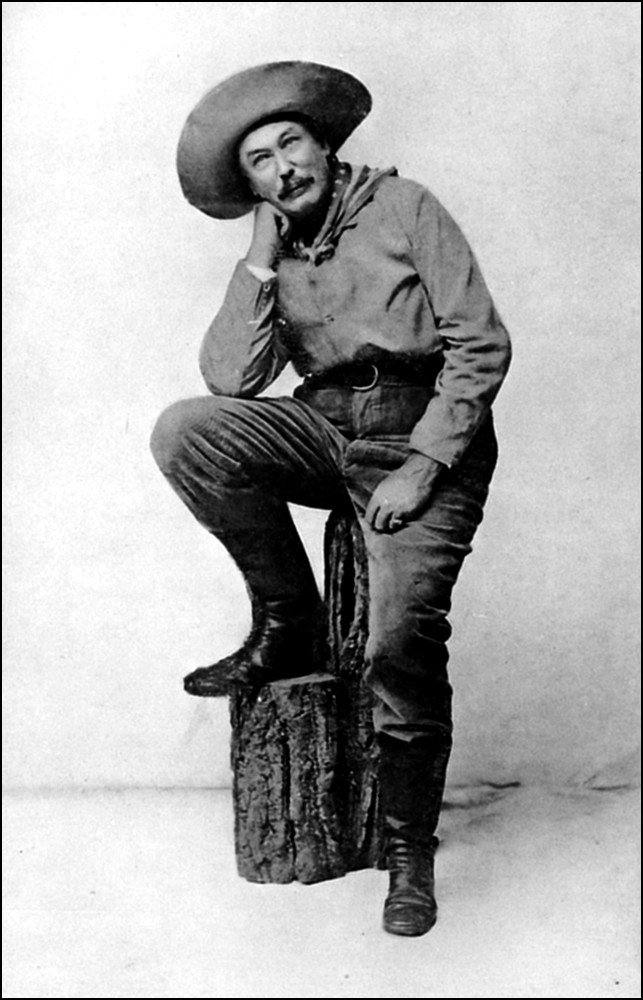

Tim Watson

The next morning Watson and Sevier saw Jack depart by the daily stage for Fredericksburgh, the latter having promised to write immediately on his arrival there, and climbing into the stage, he waved good-bye, carrying with him the picture of whole-souled honesty clad in a hickory shirt.

The great boot was strapped over the baggage behind, everything stowed away, and the driver cracked his whip over the horses’ heads as off they went. The Colorado River was not then bridged and must be forded. The horses were accustomed to it though, and even when the water reached their bellies, they still plunged on. Over the old stage road to Yuma, Arizona, they were going, and were soon climbing the bluffs west of the Colorado. From Austin, the road is one continuous rise, and by nightfall they were travelling over a rolling prairie. Jack’s only companion was a German who neither spoke nor understood one word of English, but was well armed. His own six-shooter, presented to him by Watson, was handy and he had been duly warned as to the character of the country through which they were passing.

These stages travelled very fast, stopping only at lonely stations for meals and change of horses.

It was a little past midnight; the moon had gone down, and the only sounds audible were the rumble of the coach and the distant howling of wolves. “Thirteen miles from a human habitation!” thought Jack, and a feeling akin to fear crept over him. He could not close his eyes although his companion snored loudly.

[C]Suddenly the stage came to a dead stop and crack! crack! went one shot after another. In the darkness and mélee that followed, Jack crawled out unperceived into a mesquit[D] tangle a few yards distant. The driver and his fellow passenger were summarily dispatched, their bodies and the stage plundered, and, undoing the fastenings, the desperadoes rode off with the horses. All this occurred in less time than is taken in recounting the awful deed.

Jack waited for a full quarter of an hour before he dared approach the stage. Only too well had the desperadoes done their work even in the darkness. An overpowering sense of dread came over him as he realized that he was the only remaining passenger and on a lonely plain, infested with wolves. Even now they were scenting blood, and their howls were growing nearer. One thing was certain, he must get away from this spot immediately, but where to? The darkness was so intense that he could not see two feet before him. But oh, kind Providence! in wandering about he stumbled against a tree and none too soon for as a long-drawn howl announced their approach, and the wolves pounced upon the bodies of his companions, snarling viciously as they tore them limb from limb, Jack could only be thankful for his own miraculous escape.

The wolf is a cowardly animal and never attacks a human being by daylight, nor unless goaded by hunger and sure of his position. They continued snapping and snarling for a long time. Jack was perched upon a limb out of all danger, and gradually a certain sense of humor stole over him. He was a fine whistler and often at home receptions had entertained guests with selections accompanied by the guitar. Placing two fingers in his mouth, he emitted a long-drawn whistle and as if by magic all sounds from below ceased. The experiment having gratified him beyond all expectation, Jack persevered. One selection followed another until finally the pack of probably ten wolves could be heard slinking off through the mesquit bushes.

Jack laughed softly as he said aloud,—“What would Celeste think of that for an audience?”

It was now growing perceptibly lighter. The blossom pole of the yuccas appeared like an array of bayonets and the heavy odor of the night-blooming cereus was wafted to him on the cool breezes. Soon the sun showed its yellow face on the distant horizon, shedding a warm glow over the prairie already brilliant with flowers whose names he knew not. The stage road wound like a ribbon over the plain which rose and fell “like billows on a pulseless ocean.”

Climbing down, Jack returned to the road and tramped on westward. Oh, for a drink of water; but nowhere was any to be found! One sink-hole after another was explored, only to find baked clay instead of the precious fluid. His throat grew parched as he tramped along under the burning sun, and each hour seemingly left him no farther on. All day long he plodded with no water and nothing but berries to eat.

By nightfall, away to the right and off the road, he espied a column of smoke rising. “A human habitation of some sort,” he thought, and with added courage pushed on.

Distances are very deceptive in this dry, thin air and it was almost dark when he reached the high pole fence surrounding an inclosure in which was a log house. He was about to vault the fence when a confusion of yelps told him that a half-dozen wolfish dogs regarded him as an intruder. Jack realized that these assailants were really in earnest, and hastily climbing one of the uprights, he shouted for help.

A stout German woman appeared in the doorway and, seeing Jack’s position, she shouted,—“Gerunter, Franz!” “Franz” was evidently the leader for as he drew back the others followed, and in answer to her invitation Jack approached the house which was occupied by a German family named Kurtz.

“Please give me a drink of water!” Jack said, sinking into a chair almost exhausted.

Mrs. Kurtz brought it and he drank greedily.

“Vat ist name und vo kom’st du?” she inquired in broken English.

Jack related his encounter with the desperadoes and subsequent experiences, to which she listened with an indifference incomprehensible to him.

“Ya, like Comanche,” she said, busying herself with preparations for his supper.

Oh, how good the coffee and fried chicken smelled! Jack could hardly wait for it to be ready, and when at last Mrs. Kurtz drew a rush-bottomed chair before the table as a signal that supper was ready, he went at the food in a manner which brought an expression of tenderness into even the stolid face of Mrs. Kurtz. Never in his life had he so enjoyed a meal, and his look of satisfaction attested the gratitude he felt.

This family, father, mother and daughter, were ranchers and descendants of the colony of Germans sent over by Bismarck to found Fredericksburgh. Mr. Kurtz now counted his sleek cattle by the thousand.

Jack mentioned his letter to Mr. Nelson of Squaw Creek, and his wish to go there on the morrow.

“George Nelson is a friend of mine. His youngest gal and my Elsie is real thick. Better hold on till Saturday and my gal’ll ride along with you. She wants to spend Sunday there. My da’ter is doin’ some tradin’ in town, but she’ll be home to-morrow.”

It was now Thursday so Jack signified his willingness to do so, incidentally adding that he would like to buy a horse.

“Reckon I can suit you,” returned Mr. Kurtz with pardonable pride.

But Jack was nodding, and he threw himself on a husk bed, oblivious of everything till noon the next day.

At dinner, he saw Miss Kurtz, who had ridden in from Fredericksburgh on her spirited little mustang. Her dancing eyes and brown, healthy complexion gave evidence of the invigorating atmosphere of the plains and, though somewhat shy, she was a really attractive girl of about eighteen years. Her admiration for Jack was poorly concealed and, as most young men would have done under the circumstances he set about to make himself agreeable. He described Nootwyck, his family, and gave a brief sketch of “Old Ninety-Nine’s” cave and the mine.

“Strange that they found nothing besides the mine!” Miss Kurtz mused. “Do you think that the old man taken there exaggerated?”

“No,” replied Jack, “some one had undoubtedly been in the cave recently, my father thinks, and that the money and jewels were probably carried off by the finder. All the other rare things seen by Benny must have long ago disappeared.”

“It sounds like one of Aladdin’s tales,” she said, deeply interested.

“We thought it such until the discovery,” Jack replied, “but since then I am inclined to think that many of the legends of which that valley is so full may deserve investigation. The Delawares were a noble tribe, unjustly treated, and degraded by the whites who had only themselves to blame for the atrocities that occurred in the early history of the Rondout Valley. The Delaware tongue is the most beautiful of any in the Indian language as the names in our county testify.”

Seeing a piano, Jack asked Miss Kurtz to play. She complied, but the piano was wofully out of tune, and she expressed great regret at her inability to get a tuner, saying her uncle usually attended to it, but he had recently been shot.

“If I had the implements, I could do it for you,” he replied. With a grateful look, she ran out of the room, returning almost immediately with a pair of saddle-bags in which was a complete tuner’s outfit.

“There,” he said, “I’ll soon have your piano in shape.”

“And while you are about it, I’ll help mother with the work,” she smiled, leaving the room.

He had almost finished his task when Mr. Kurtz came in to ask if he wished to see the horses and, as Jack was still busy, he sat down in the doorway to wait.

Jack seated himself before the instrument to try it, running his fingers lightly up and down the keys. A correct ear told him that the work was well done and, rising, he followed Mr. Kurtz into an inclosure where were several horses.

“There,” said Mr. Kurtz, “I have several as fine specimens of horseflesh as you ever saw.”

They were indeed fine animals, but one in particular attracted Jack’s attention. He pointed out the horse and Mr. Kurtz said, “That’s Clicker, my woman’s saddle horse.”

At the sound of his name, Clicker pricked up his ears and whinnied.

“Your wife’s saddle horse!” Jack repeated in astonishment.

“Sartin,” returned Mr. Kurtz, and chirruped softly to the animal which trotted gracefully up to him, rubbing his velvety nose on the old man’s arm.

The horse was a light bay, fully sixteen hands high, magnificently muscled, broad forehead, intelligent eye, gracefully arched neck and luxuriant mane and tail.

Jack, a real lover of horses, took in all these good points at a glance and determined to own him if money could buy.

They were here joined by Elsie, who threw her arms around Clicker’s neck, kissing and petting him; then, turning to Jack, she said,—“Is he not superb?”

“The most magnificent horse I ever saw, but I should never take him for a lady’s horse.”

Elsie laughed as she said,—“Clicker is a gallant. Why, children climb up his legs while he looks approvingly on, and with a woman on his back he is simply a lamb. Just mount him if you are a fearless rider and he’ll behave accordingly.”

At first, they flatly refused all offers; but Jack’s offer of seventy-five dollars proved too tempting and the bargain was closed, Mrs. Kurtz adding the saddle that had belonged to Elsie’s uncle.

They would receive no pay for Jack’s accommodation, evidently considering the obligation on their side. Western hospitality is noted for its breadth, but never before had Jack appreciated the full meaning of the word and he was greatly affected by the honest simplicity of these Germans.

Early Saturday morning Jack and Elsie started for Squaw Creek Valley, ten miles distant. It received its name from the fact that when the Comanche warriors went out on their raids, the squaws were left in this valley on the banks of the stream.

Clicker’s step was light and springy as a panther’s and his motion so easy that Jack felt as if in a rocking-chair. Elsie sat on her pony like the practised horsewoman she was. They were galloping over the cattle trail which at times was invisible, and they then gave their horses rein as every foot of the ground was familiar to them. Jack noticed with admiration how deftly the animals avoided the thorny mesquit and cacti.

Herds of sleek cattle grazed on the prairie covered with mesquit and buffalo grass. The former is the best in the world. It grows luxuriantly upon the plains of Texas, renews itself early in the spring, matures early, and throughout the year remains nutritious as naturally cured hay. Innumerable varieties of cacti blazed their gorgeous blossoms of yellow, red, pink and white over the expanse, but no trace of water; for it had now been six months since they had had any rain, and Jack marvelled at the healthy look of vegetation. “How is it,” he asked, “that the trees attain such size and look so thrifty?”

“It is a common saying in these parts that their roots are attached to the bottom of a subterranean lake which is supposed to underlie this county,” laughed Miss Kurtz.

Jack also laughed as he answered, “Then why is not someone enterprising enough to utilize these everlasting winds in bringing some of the water to the surface? Honestly, I wonder that you do not irrigate.”

“One or two have tried it, but the water is very, very deep, and the scheme is an expensive one.”

“This soil is a rich, dark alluvium, very productive without rain. What would it produce with it?” he continued.

“Prickly pears and all the other varieties of cacti,” Elsie replied demurely.

They were now nearing a series of bluffs which gradually arose to an elevation of about one thousand feet forming a wall, or chain of hills, which hemmed in Squaw Creek Valley on the east for its entire length of seventeen miles. Their ascent was gradual, trees grew smaller with elevation and soon they were picking their way through a tangle of shin oak, cacti and mesquit bushes. Exhilarated by the pure air, they halted on the summit and looked down into Squaw Creek Valley. Jack started at its resemblance to his own dear valley in the North, only the walls which hemmed in this one would be called hills there.

At the head, or rather three heads, of the valley, Squaw Creek has its source in a chain of small lakes of pure spring water; thence it winds its way through the entire valley and at the extreme northern end unites its waters with the Onion to form Beaver Creek which empties into Llano River. The valley itself appears perfectly level and its walls have a perpendicular height of nearly five hundred feet. The road into it was at the northern end.

For several miles they travelled along its summit, then, descending abruptly into a pass, struck the stage-road for Fredericksburgh and dismounted to water the horses. As Jack was assisting Elsie to alight, her watch slipped from her belt and fell to the ground. In stooping to pick it up, he was struck with its unique workmanship. “May I examine it?” he asked. “I never saw one like it.”

“Certainly,” she answered, handing it to him. “It belonged to a Spanish woman who died at our house. I nursed her and just before her death she gave me this, saying it was all she had; and this,” opening the back of the watch, “is a miniature of her only child. She called him Hernando.”

“My God!” exclaimed Jack, greatly agitated. “Tell me all she said.”

“She left a package of letters for her boy should his whereabouts ever be discovered, and I have kept them securely locked. Mother said it was useless to try to find him.”

Jack’s eyes were blurred with tears as he looked at the picture; the same wonderfully blue eyes and golden hair. Even as a boy, the sensitive mouth showed a downward curve. Jack leaned his head wearily against Clicker’s neck, as he said: “Miss Kurtz, in befriending this Spanish woman, you have placed the discoverer of ‘Old Ninety-Nine’ under a debt of deep gratitude.”

She looked puzzled and he continued, “This is a picture of Hernando Genung who located my father’s mine and developed it too. He is a hero and a martyr and you may well prize his picture.”

“But I shall send it to him along with the letters,” said Elsie.

“No,” Jack protested firmly, “wear it always, but give me in writing a full account of his mother’s time with you and I will forward that and the letters to my father.”

Jack’s cheeks were colorless and his wan look made Elsie’s heart ache. Something more than ordinary grief was back of this, but she dared not speak and felt greatly relieved when they drew up before Mr. Nelson’s house.

It was a one-story adobe building built around a courtyard and around this ran a piazza onto which a door from each room opened. In front was a large central door, and opposite this was another leading to a corral in the rear. The windows were small and placed high.

They saw Mr. Nelson himself coming by a well-beaten path from the creek. He had evidently not heard their approach for his glance was fixed on some object up the stream but on turning an angle he saw them and a hearty “Howdy!” indicated that Elsie was no stranger. He shook hands warmly, scanning Jack’s letter as a matter of secondary consideration.

Nine of Mr. Nelson’s children were married and settled in homes of their own and Dora, his remaining one, now approached with her mother.

Texas hospitality again. The best they had was literally his while under the protection of their roof and Jack was made to feel that he conferred a favor in accepting it.

Dinner was soon ready and seated at that hospitable board, Jack first tasted the succulent steaks which had heretofore existed only in his imagination.

“I reckon that this is your first meal in a ’dobe house,” remarked Dora.

“The first one I ever entered,” Jack returned, “and it has a distinctly foreign air.”

“Well,” said Mr. Nelson, “I spent some time in Mexico and their manner of building struck me as suitable to this climate. ’Dobe is cheap and durable.”

Jack’s head throbbed painfully and he could not conceal his suffering. The strain he had been under for the past week, with the shock received that morning, had completely prostrated him, and he was only too glad to follow Mrs. Nelson’s advice and go to bed. His room was sweet and inviting, but he sank into bed too ill to appreciate it.

For two weeks he was confined to his bed and when able to sit up his eyes fell on a small box, on a stand beside the bed, which Dora said had been brought by Elsie.

“Will you kindly hand it to me?” Jack requested. Dora complied and she was about to leave the room when he protested and she resumed her seat.

Jack’s hand trembled as he took the box and Dora’s eyes were moist when he looked in her direction. Was it the attraction of her womanliness which made him lay before her the awful fate of the one to whom these letters belonged? Gradually he spoke of himself, his aspirations, his plans for the future with its seemingly infinite possibilities all gone now. “There is no use in longer deceiving myself. My future in this world lies in the past.” His tone was bitter and though evidently relieved by unburdening his mind, he seemed utterly crushed.

“Mr. De Vere,” said Dora resolutely, “what you tell me is indeed terrible. I do not pretend to understand why one endowed with so many noble qualities should be thus stricken. An orthodox Christian would tell you that it is the will of God that it should be so and you must pray for strength to bear it. Never mind that, you have something more tangible to deal with and that is your own physical condition. ‘Self-preservation is nature’s first law,’ and it is your duty to obey. Are you doing it? You are utterly cast down, oblivious of the many blessings around you. The doctor says if your nervous system would react—which lies in your own power—in this dry, thin air, your lungs would undoubtedly become restored to a healthy condition. Brooding over misfortune is sinful. Forgive me if I wound you, but no one excepting true friends point out our shortcomings.”

Jack seemed in a quandary as he replied quietly, “Leaving out all superfluous words, you mean that I am a coward.”

“Not exactly coward, but you are shirking a grave responsibility.”

“A shirk, then,” he corrected. “You are very frank, Miss Nelson.”

But Dora was out of the room by this time, leaving him wholesome food for reflection. More than anything else, Jack detested a “coward” or “shirk,” and the thought of his appearing in the guise of one was not pleasant. It nettled him, but his judgment told him that Dora’s philosophy was sound, and when the doctor next came, he saw a decided change for the better in his patient. Soon he was able to go for a short ride on Clicker, and the doctor exchanged knowing looks with Mrs. Nelson.