CHAPTER XI

AUGUST came and for nine months not a drop of rain had fallen. The earth looked burned up, and the grass was so dry that in travelling through it it flew into dust which the wind sent whirling over the plain. No crop promised to be a good one. The sun beat pitilessly down on the brown fields and cattle subsisted mainly on mesquit beans that dangled their long pods in the never-ceasing wind.

“All in the world this country needs is water,” thought Jack who was studying irrigation schemes. Water from the streams was impracticable and he now decided to bore on his tract of one hundred and sixty acres just northeast of Brockman’s Point, and have his irrigation plant ready and in operation by the middle of September, superintending the work himself. But it was well into December before the work was completed, and he was returning from a final inspection when whom should he meet but Tim Watson.

“Howdy there, young Yank!” the latter called out to Jack.

“Well I declare if it isn’t Mr. Watson!” Jack shouted, bounding forward.

Watson eyed the brown, healthy specimen of manhood before him admiringly and remarked on his improved looks. “Your cousin sends her regards and this,” said Watson, handing Jack a parcel which he opened immediately. It contained a pair of moccasins, embroidered by Miss De Vere herself, and an extremely kind letter.

Jack’s eyes filled with tears of pleasure at the acceptable present and the spirit that prompted her to make it.

“She is very kind to take such an interest in a comparative stranger,” he said with great feeling.

“She is a De Vere, you know,” Watson answered, slyly punching him. “Is Nelson about?” When answered affirmatively he continued, “Dora is a nice girl, now, aint she?”

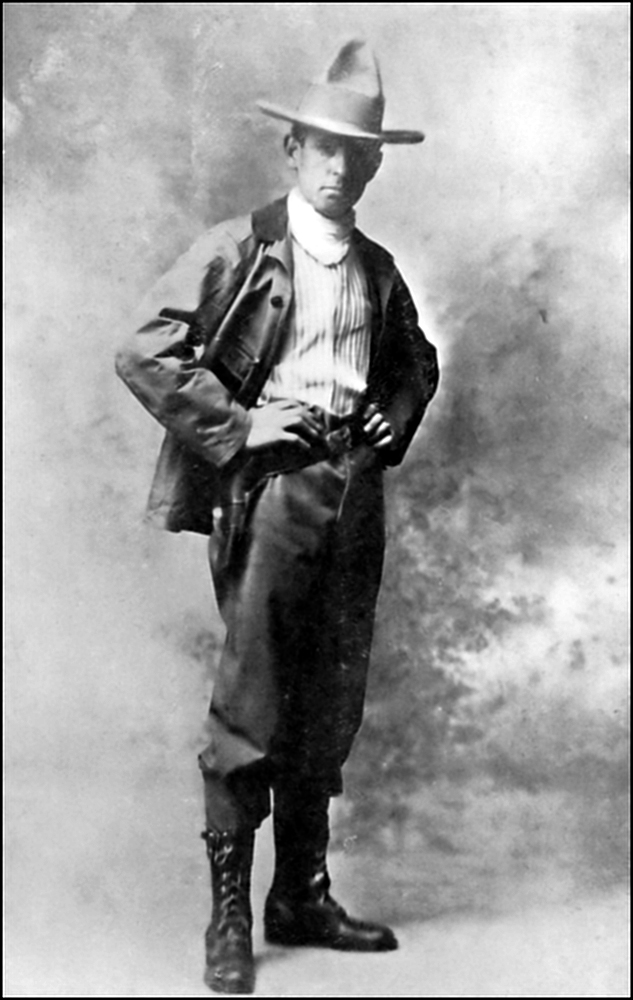

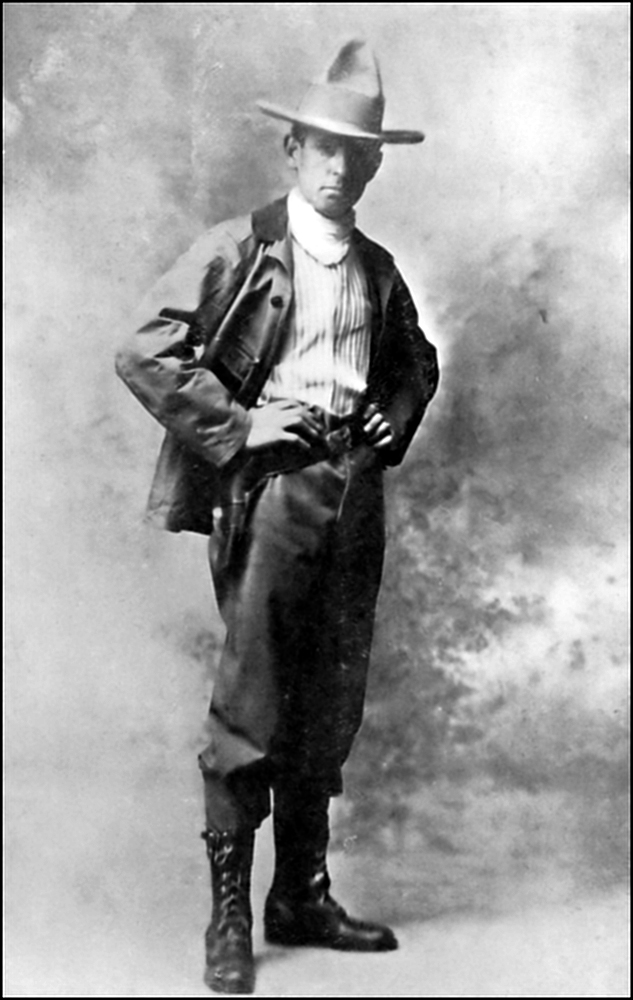

Jack De Vere

“Certainly,” replied Jack quickly, “a fine character.”

Watson eyed him closely and then burst into a loud laugh which was so infectious that Jack joined in without knowing why. Suddenly checking himself, he said, “What are we laughing at anyway?”

“You sly dog,” said Watson, “I’ve been there myself, and you needn’t try to look innocent. She’s a jewel, my boy, and I reckon you’ve done the right thing.” Then changing his tone, he continued:

“After you left Austin, I wrote Andrew Genung stating that I had seen you, and made some inquiries about his brother and what had become of the boy Hernando. He answered at great length telling me that, as I knew, his brother Fred had died in a fight at Virginia City. The wife is probably—God knows where!” Here his voice sank to a whisper, “And their boy is a leper! Did you know this?”

“Yes,” replied Jack, “and I know that that poor Spanish woman died a victim of treachery.” And Jack gave an account of the letters left with Elsie Kurtz, also of what the Spanish woman told her of how a man by the name of Bruce poisoned her mind against her husband, and under the guise of a friend enticed her from home one night; that her husband overtook them, would not listen to her protestations of innocence, shot them both, as he supposed, mortally and left. When she came to herself she was alone and covered with blood. She dragged herself back to Virginia City feeling sure that her boy Hernando would believe in his mother’s innocence; but no trace of either him or his father could be found. Unable to bear the slights and jeers of former companions, she wandered about until she fell in with a family of Mexicans bound for southern Texas. They pitied and cared for her and she made her home with them until about three years ago when she drifted among the Greasers in this part of the country.

Watson’s expression during this recital was first one of surprise; this changed into astonishment, and then a look of such vindictive hatred that Jack proceeded with difficulty; but when he had concluded, his listener remarked coolly, “I’ll be doggoned if I aint hungry!”

“Were you ever North, Mr. Watson?”

“Never, but I reckon I’ll go some time, perhaps along o’ you when you take a turn home.”

“Oh, how delightful! I may go next year.”

For dinner, they were served with blue cat-fish of which Jack never seemed to tire, a long, slender fish averaging about one and a half pounds, and equalling in flavor the northern brook trout. It is very unlike the mud cat-fish which is coarser in grain and flavor and sometimes attains a tremendous size; but even from a fifty-pound fish, the steaks are very good.

“I do not believe there is a fish in the world equal to our blue cat-fish,” observed Watson, deftly removing the bones from his mouth.

“Unless it is our speckled trout,” Jack suggested.

“There is a peculiar spring on my ranch,” said Watson abruptly; “in dry weather it is full of water, but in time of rain there aint a drop in it.”

“I can beat that,” laughed Jack. “Just back of Sampsonville in the town of Olive, and nearly at the top of High Point, four thousand feet high, is a spring called the ‘Tidal Spring’ because, when the tide is in, the spring overflows, and when it ebbs the water lowers.”

Jack looked quickly in Watson’s direction. For an instant their eyes met and the answering glance told that in Ulster County was still another spring where, in durance vile, was being served what seemed an unjust term.

After a long silence, Watson shook himself like a great dog and turning to Jack said,—“Young man, I reckon you think I’ve come just in compliment to your irrigation plant, but you’re mighty mistaken if you do. They’ve made a big strike of gold down in the Llano District. I’ve always believed there was gold there, for the formation is similar to that of the well-known mining camps in Colorado. Some years ago in panning the gravel in the streams and gullies I found colors of gold. The granite in that section has been crumbling away for ages, the debris covering the formation. Report is, that in the side of the gully at the foot of Mt. Fisher, a narrow seam of quartz not more than an inch wide that shows gold and assays eighty dollars to the ton, has been discovered.”

“The very thought of exploiting another vein makes me sick,” said Jack.

“But,” replied Watson, “already a number of loads of high-grade selected ore have been taken from the surface trenches and sent on to the Colorado smelters. The mine is being rapidly developed, and assays are running up into the thousands. Are you going to let a chance like that go by?”

“I want nothing to do with it,” Jack insisted.

“Further report says,” continued Watson, “that the strike in the Mt. Fisher Mine is of such a remarkable character, both in richness and extent of the veins, as to prove beyond a doubt that this belt is as rich in ore as any in Colorado.”

Jack remained stolidly indifferent and, really annoyed, Watson said hotly,—“Reckon you can leave your damned irrigation plant long enough to ride over there along o’ me in the morning?”

“I’ll go with pleasure—would really enjoy the ride with you. When do you propose to start?”

“Long afore daylight.”

Nights are always cool enough to sleep under a cover in Texas and the morning that Watson and Jack started for the mining camp, they found it necessary to wrap themselves in their blankets.

During the winter season all ranchmen on starting out for a trip of any length go prepared to encounter one of those terrible “northers,”[E] and carry with them a twenty-five pound sack in which are bacon, biscuits, coffee, a coffeepot and tin cup, a lariat and hobbles attached to the saddle.

Three miles out of the valley where the stage road forked with the one leading to Fort Minard, Watson and Jack took a north-easterly course for the Llano District, following an old cattle trail. Almost every bush and plant in Texas has a thorn and, as they threaded their way through clumps of parched buffalo grass and weird cactus plants, Jack appreciated the value of “chaps.”[F] The soil was very dry and every step of the horses sent clouds of dust whirling; but the air, stirred by the warm breeze, was delightful, and Jack felt his lungs expand with a vigor heretofore unknown. That annoying cough had quite disappeared, and no one would dream of accusing him of being a prey to ill health. Like a new being, his pulse bounding and mind alert, he galloped over the plain beside Watson with the keenest enjoyment.

They were now sixteen miles from Squaw Creek settlement and following the creek washes of the Llano River. Clicker had shown signs of uneasiness and occasionally gave an ominous snort.

“What can be the matter with this horse?” said Jack. “He seems determined to make for that streak of woods yonder.”

“Matter enough! He knows a heap more than we do! To the bushes!” Watson shouted, whirling his horse about.

Clicker needed no urging. Jack felt those powerful muscles quiver under him and with one bound the animal cleared the ground ten feet. Like an arrow he flew and, bending low in the saddle, horse and rider appeared like a cloud of dust.

In an incredibly short space of time, the haze in the north had wholly obscured the heavens and a biting north wind accompanied by sleet pitilessly drove them back; but twenty minutes brought them to a position of comparative shelter. The horses discovered a rude shed into which they dashed and, jumping to the ground, Watson and Jack endeavored to make their shelter more complete. Evergreen boughs were piled up around the more exposed parts and as the roof seemed tight, they congratulated themselves on having found this haven. Next, they brought in wood and started a fire.

“We want a powerful sight, my boy. A ‘norther’ means business. When we do get things here we get ’em hard,” said Watson.

Nearly all the afternoon they worked with a will, bringing in fuel and whatever fodder for the horses they could find.

Fiercer and fiercer the wind blew and the sleet dashed against their shelter as if determined to gain access. Great trees were torn up by the roots and the crashing was fearful. Sounds of distress from herds of cattle huddled together in the woods came to their ears. Cattle seem to scent these storms, and try to reach a place of safety; but the weakly ones frequently perish on the plains.

Jack found an empty kettle, an immense black one, in one corner of the shed. It was cracked entirely around the bottom and a blow from a billet of wood knocked the bottom out. This he placed over the fire leaving a draught-hole in one side and thus the coals were prevented from being blown about, although their eyes suffered from the smoke.

Watson deftly sliced some bacon with his jack-knife, the coffee was soon boiling, and with a relish of a perfect appetite for sauce, they pronounced their supper “fit for a king.”

Their stove soon became red-hot and Jack said they roasted on one side while the other froze. How he pitied the poor animals outside, but it was better than the open country.

They decided to divide the night into watches, and as Watson was already nodding, he consented to turn in first and was soon snoring, lying with his back to the fire.

Jack was no coward, but the weirdness of the situation impressed him and with every sense on the alert, he prepared himself for any emergency. The fire was kept burning and his rifle ready.

One o’clock. Suddenly a screech as of some human being in distress sounded not twenty feet from their shelter.

Watson sprang up, pistol in hand, and seeing nothing, exclaimed impatiently, “I aint deaf, that you’ve got to yell like that to wake me.”

Jack was about to explain when again that awful screech.

“A painter, by gosh!” said Watson, himself laughing. “Have I been asleep?”

Jack restrained a smile as he answered in the affirmative and Watson said as he was now awake he’d better get up, so Jack warmed over the coffee.

“Jerusalem!” Watson exclaimed, looking at his watch. “One o’clock! Why, boy, why didn’t you call me before?”

Jack protested that he was not sleepy but Watson made him turn in. “Steady your nerves, they’ll get a shock when we reach the mining camp. Now don’t say I aint told you.”

Daylight showed nothing but sleet driven by an Arctic wind, and they had the dreary consolation of knowing that in all probability it would continue for three days; but Watson was an old frontiersman, full of stories.

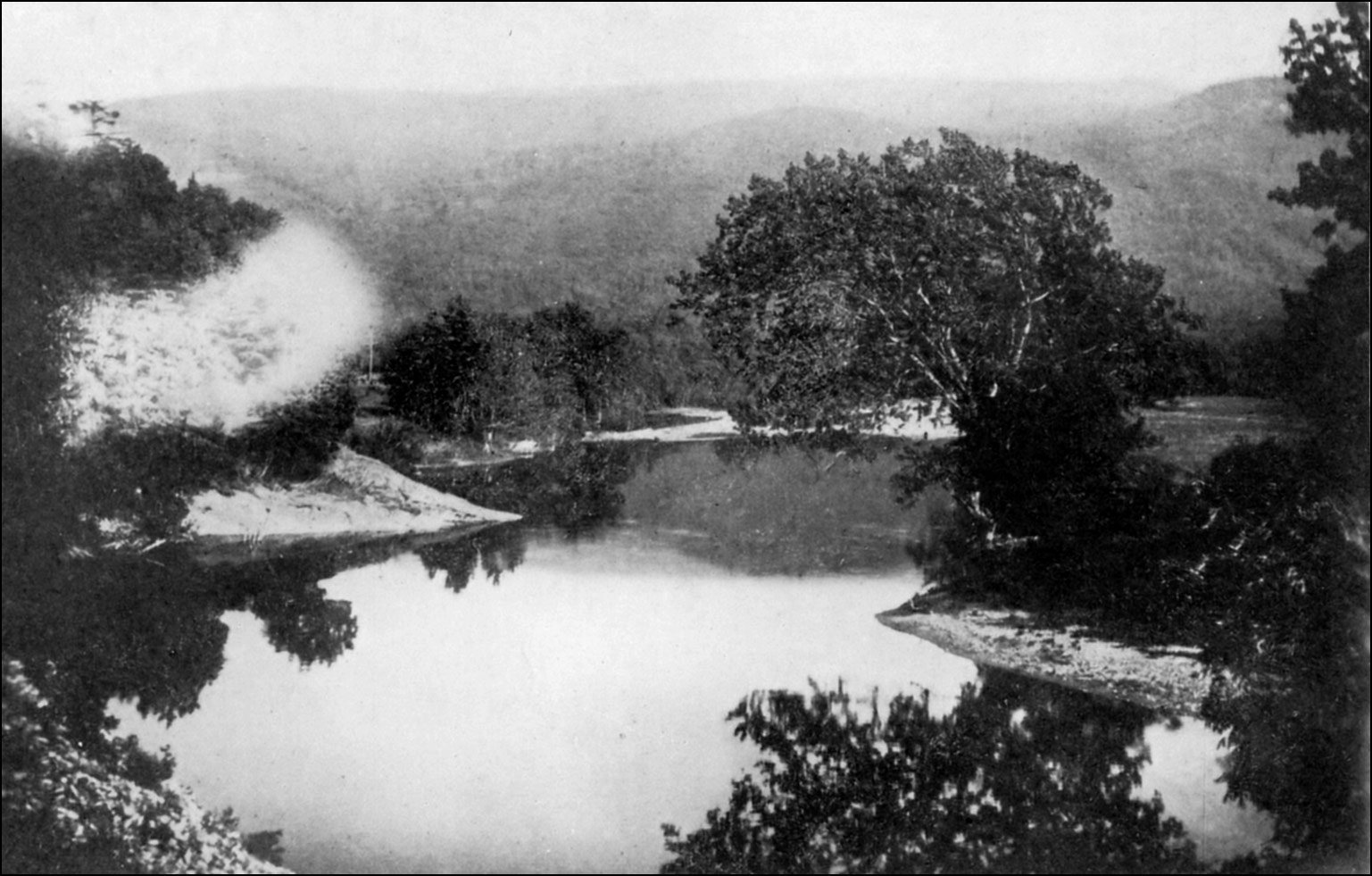

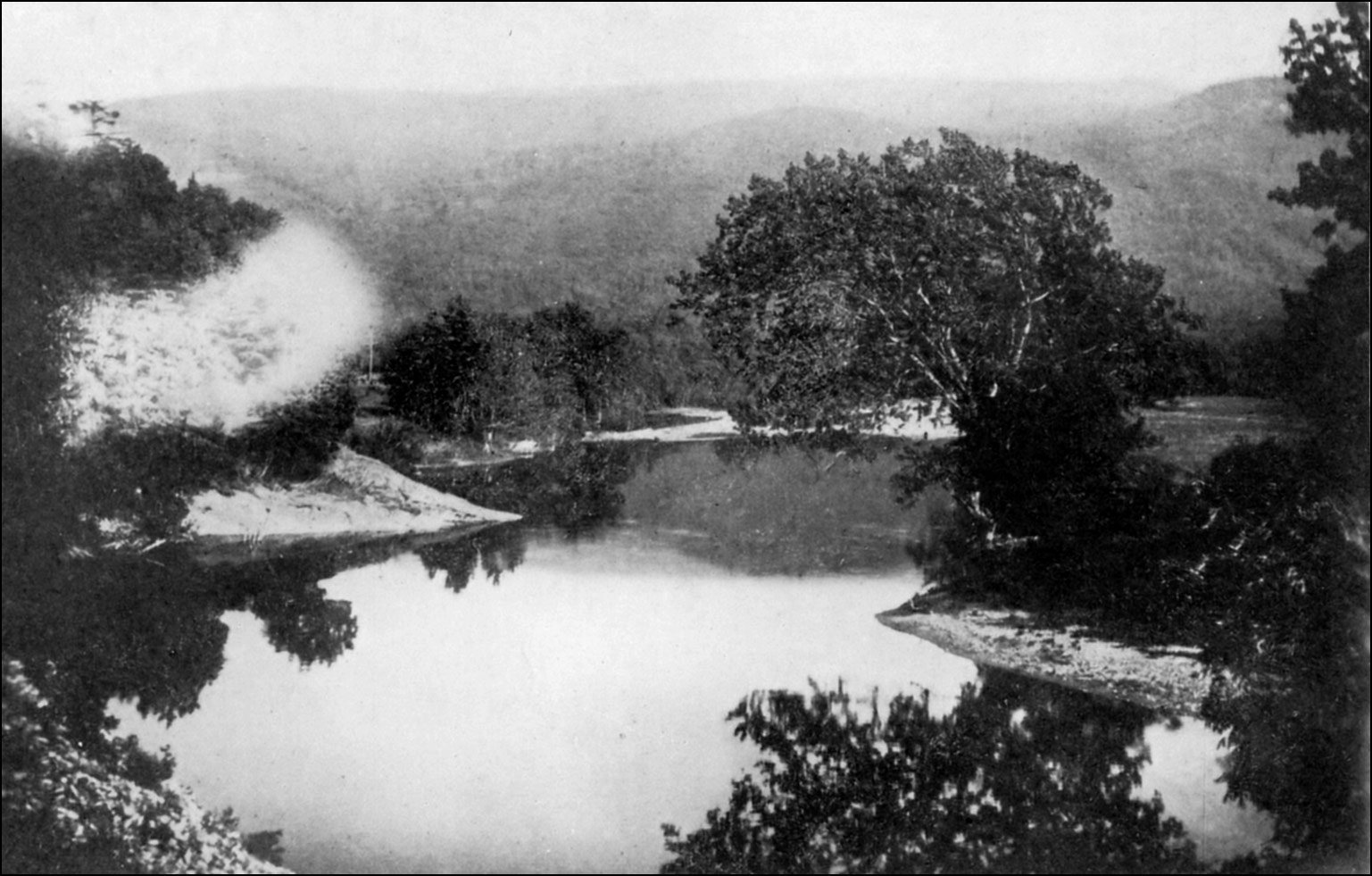

On the third day the storm visibly lightened. The wind coming in fitful gusts indicated that its force had been spent, and it finally ceased altogether, so that on the next day, they resumed their journey. The trees were so weighted down with ice that many limbs had broken off, thus impeding progress, and to any but horses accustomed to this tangled undergrowth rendering it dangerous. Threading their way cautiously, the open country was finally reached and, after a short halt, they mounted and rode on to Mt. Fisher, turning a deaf ear to the moans of distress from injured cattle on their way. On they sped, Mt. Fisher seemingly not more than a mile distant, and beyond the hills melting into a pinkish haze. The whole scene was typical of absolute freedom and Jack was enjoying it to the fullest extent when Watson suddenly called a halt and, reining his horse beside Clicker, said earnestly,—“Do you recollect that I warned you of a surprise at the mining camp?”

Beyond the hills melting into a pinkish haze

“Yes.”

“Are your nerves steady?”

“What do you mean?” Jack asked hotly.

“Just this. You are going to meet two old acquaintances, namely, Sheriff Smith of Nootwyck and a man you know as Valentine Mills; and my reason for not telling you before is I knowed you’d wear yourself out before we got here.”

“What the deuce is Mills doing here, and how long since you turned detective?”

“Well, I aint studied human natur’ all these years for nothing, and when you told me of Old Ninety-Nine’s mine, something you dropped carelessly about Valentine Mills set me to thinking, and this ended in acting, with the result that it is proved beyond a doubt that Valentine Mills and Robert Bruce are one. I aint particular sharp, just been doin’ a little missionary job. I haint no time for just ordinary sinners but when God Almighty blazes a trail straight to a stomped-down, pusley-mean, miserable coyote like Robert Bruce alias Valentine Mills and all his other aliases, it’s my bounden duty to convert him!”

“Is Sheriff Smith at Mt. Fisher now?”

“Yes, he is to meet us in that piece of woods yonder,” pointing to the left. “There he’ll wait. It’s only a few rods from the mine, and you’re to go on ahead to open the way.”

“I’ll do it with a right good will,” said Jack in a voice that boded Mills no good.

“We’ll be on the watch, and when your right hand goes up, Sheriff Smith’ll appear on the scene, and at his signal I’ll show up. I reckon he won’t be proper glad to see me!” Watson chuckled.

In another half-hour they reached the woods by a trail that concealed them from view and their low “Hello” was answered by Sheriff Smith, who anxiously awaited their coming. Like Jack, this was his first experience in a “norther,” but he had been more fortunate in not having left Fredericksburgh until that morning.

Sheriff Smith was a typical mountaineer, tall, muscular and without an ounce of flesh to spare. No one had ever been hung in Ulster County—his enemies hinted, much to his regret.

This morning he was positively affable and, after briefly delivering many messages to Jack, turned toward Watson inquiringly.

The latter’s plan seemed a good one, so, leaving his horse, Jack proceeded at once to the mine. Reaching the shaft, who should spring lightly from the bucket but Mills himself! Instantly his glance fell on Jack, he threw his arms around him in an ecstasy of delight, overwhelming him with solicitous questions. “Oh, my dear boy!” he said, wiping his eyes, “forgive this emotion. Such unexpected pleasure completely unnerves me!”

Jack shook him rudely off, throwing up his right hand as he did so; and while Mills was still wiping his eyes, Sheriff Smith’s hand was laid on his shoulder and the words, “You are my prisoner!” quickly dried his tears. Turning toward the miners who had collected near, he said in an abused tone,—“Friends, what is the meaning of this?”

“I’ll explain that,” Sheriff Smith interjected. “Three indictments are pending against you: abduction, theft and robbery; but at Nootwyck you’ll get a chance to clear yourself.”

“Who accuses me of abduction?” Mills asked defiantly.

“Andrew Genung of Nootwyck,” was the calm reply.

“Now look here, Smith,” said Mills. “This is a plot concocted in the brain of that rascally nephew of Andrew Genung. Genung is far too sensible a man to cause my arrest on some trumped-up charge with no proof that I committed the deed.”

“Aint there no proof, Robert Bruce?” and Tim Watson stepped before him.

Mills’s blood receded from the surface, leaving his countenance a ghastly green. Dumb with fear, balked at every turn, realizing that his last card in this desperate game had been played, he fell on his knees and begged for mercy.

Not a man present thought him worth a decent kick and all shrank away from him in abhorrence.

Quick to see his advantage, Mills sprang past them toward the woods, like a cat.

“Halt!” called the sheriff.

But Mills heeded not, and when the smoke which followed the bullet from Sheriff Smith’s revolver cleared, it was plain that Mills’s case would be tried in a higher court than Nootwyck.