CHAPTER XIII

EVERY day brought to light some new trait in Hernando’s character. He seemed absolutely unselfish and always called up the noblest qualities in others. His interest in the mine was unabated and although Elisha insisted upon relinquishing the position of superintendent, claiming he held it only by proxy, Hernando refused so decidedly to accept that he was obliged to desist. He consented, however, to become his assistant.

Among Cornelia’s friends was a young Mr. Van Tine. He was a frequent visitor at the house, nearly always forming one of their excursion parties; but Cornelia was looked upon by the family as simply a child, and Mr. Van Tine, whose father was one of the oldest settlers, had been Cornelia’s school-fellow so he was “George” Van Tine to them all.

Mr. and Mrs. Van Tine lived on a farm in the outskirts of Nootwyck. They were devout Methodists and intended that George, their only child, should be a minister of that denomination. His education was shaped accordingly till the age of eighteen, when he flatly refused to follow the ministry as a profession. Prayers that he might be brought to see the error of his way followed, but he persisted. Next he was taken from school and set at learning a trade, that of ornamental painting. This was something tangible and, having artistic taste, he excelled in it, and his parents became in a manner reconciled. They considered an education as wholly unnecessary to a business life, as a sinful waste of time. George was a natural mechanic; as a child his tastes ran in that direction. When he grew older he expressed a wish to become an architect but this was tabooed. He, however, submitted a design and, crude as it was, it showed genuine skill and received considerable praise. He simply waited his opportunity to perfect his talent.

Elisha and he were the best of friends. Cornelia had told the former of George’s disappointment in not being able to receive a thorough business education and, with characteristic readiness to aid others in any worthy object, Elisha took him under his own supervision with most gratifying results. Now, at twenty, George had obtained his parents’ consent to enter the Institute of Mechanical Arts at Nootwyck, and in two years he looked forward to the attainment of his long-cherished ambition.

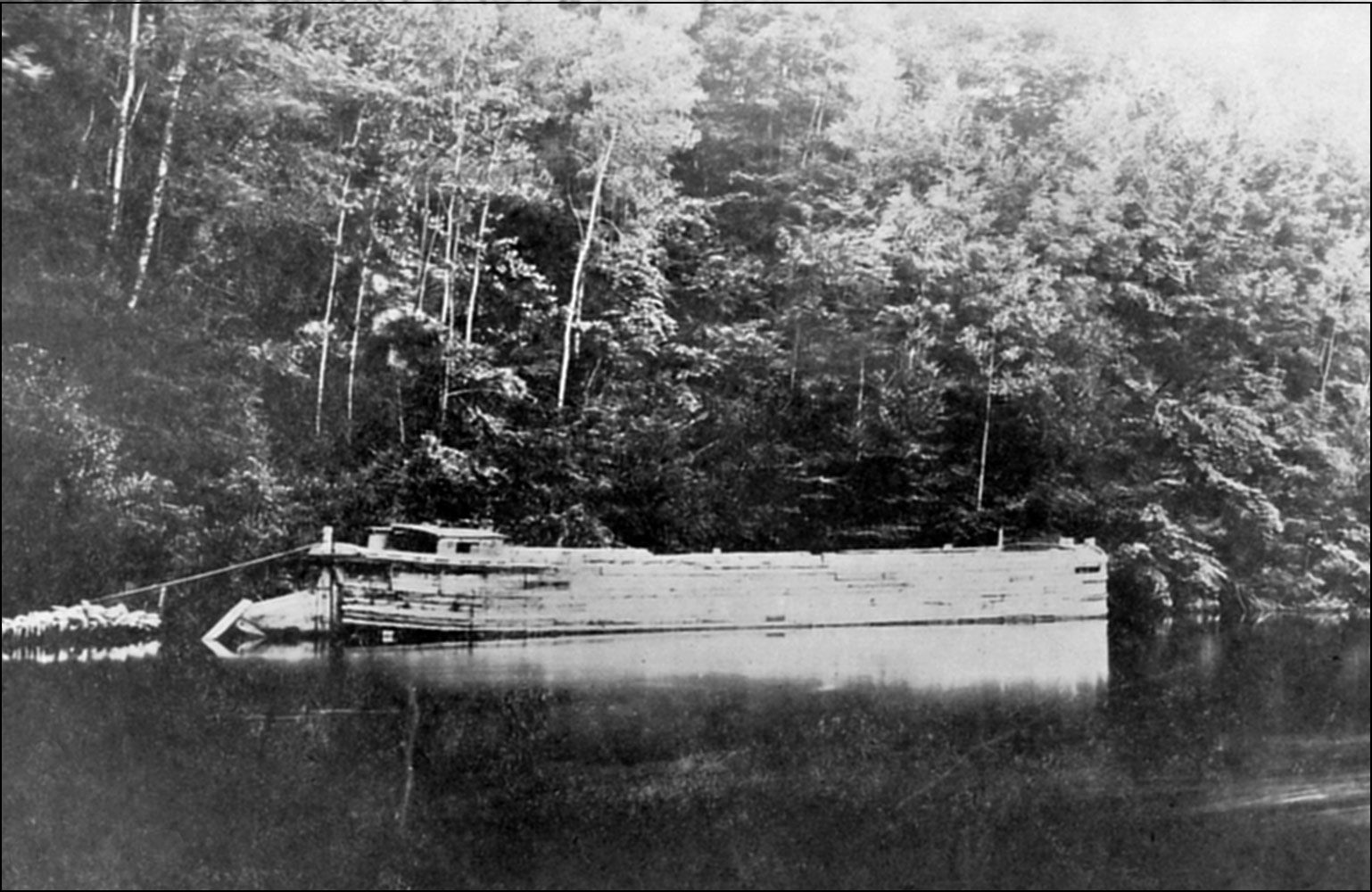

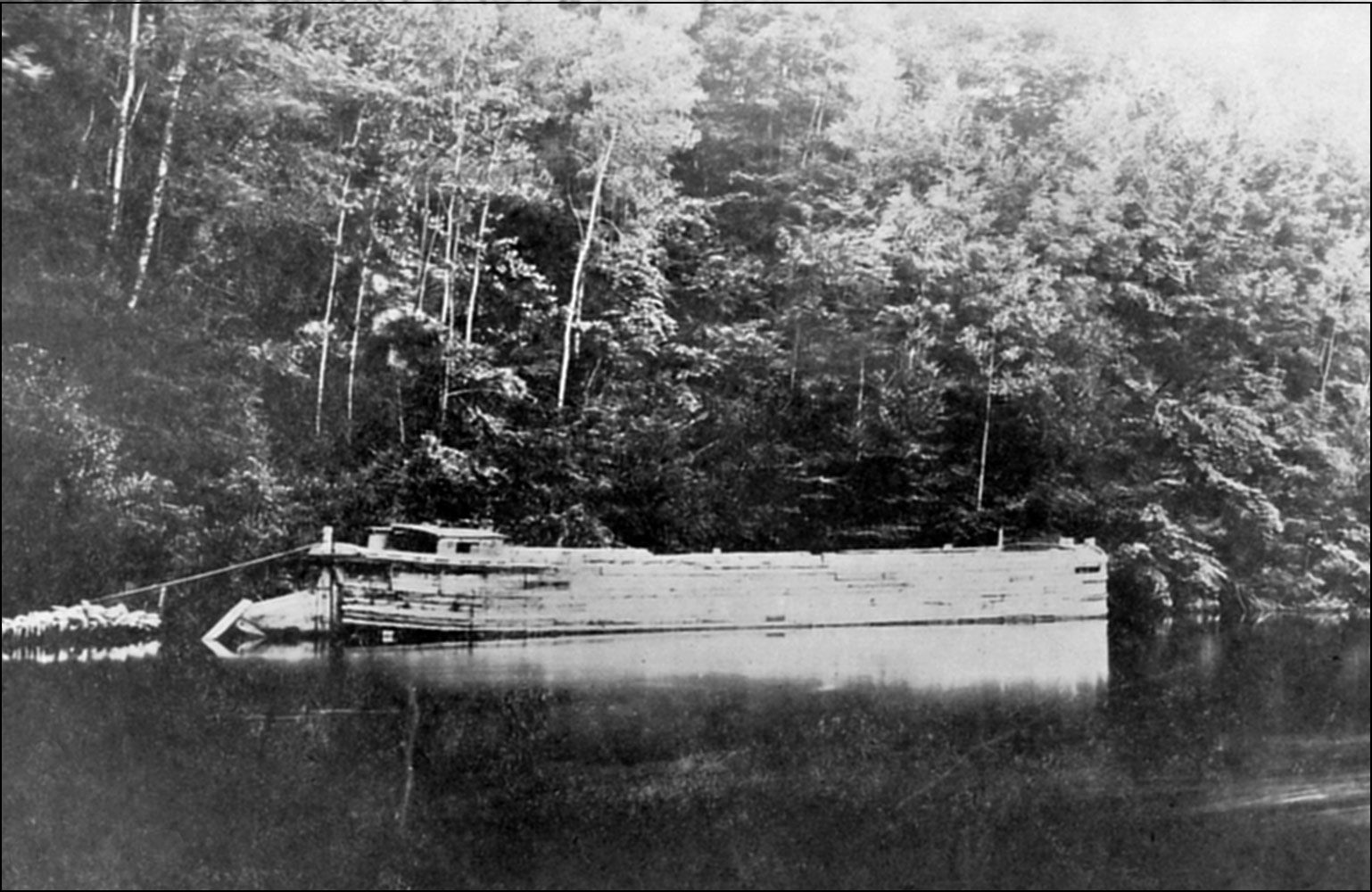

June arrived with its sunshine and roses and one ideal morning before the sun peeped over the mountain, the entire household at The Laurels, including George Van Tine, started by wagon for Sam’s Point. The dewy air was fragrant with flowers and birds twittered joyously among the trees. Deliciously fresh and cool seemed the old Berm which they were following. Canal boats still crept sleepily on between Honesdale and Rondout, but the old boating days were almost over and would soon exist only as a memory of something that had served a good purpose. Past the path to the ice caves where, in caverns hundreds of feet deep, nature provides an abundant store of ice at all seasons of the year. In their vicinity, the mountains seemed to have been rent by some convulsion of nature that split the solid rocks into chasms from two to twelve feet wide, about one-half a mile in extent, and perhaps two hundred feet deep. Geologists say that they are not of volcanic action but caused by the gradual cooling off of the earth’s surface.

Canal boats still crept sleepily on

Soon the road was steadily up and they halted frequently to rest the horses and enjoy the view below. Dora had never seen the mountain laurel, and the mountain sides were literally pink with blossoms.

“Oh, how beautiful!” she exclaimed, examining a superb bunch that Hernando had picked for her. “The symbol of victory.”

“I regret that this is not the ‘Laurus Nobilis,’” Mr. De Vere replied. “That could not stand our climate. The Indians called this ‘Spoonwood,’ and utilized the fine-grained knots for making spoons.”

“Some of the old settlers about here call it ‘Calico Bush,’” Eletheer laughed. “Is not the name appropriate?”

“Eletheer knocks the sentiment out of everything,” Jack retorted. “She will probably tell you, Dora, that the leaves are poisonous, so don’t eat them.”

“I’m hungry enough to eat anything,” Dora replied.

“Score one for Dora,” joined in Cornelia. “I’m thankful that we’re almost there.”

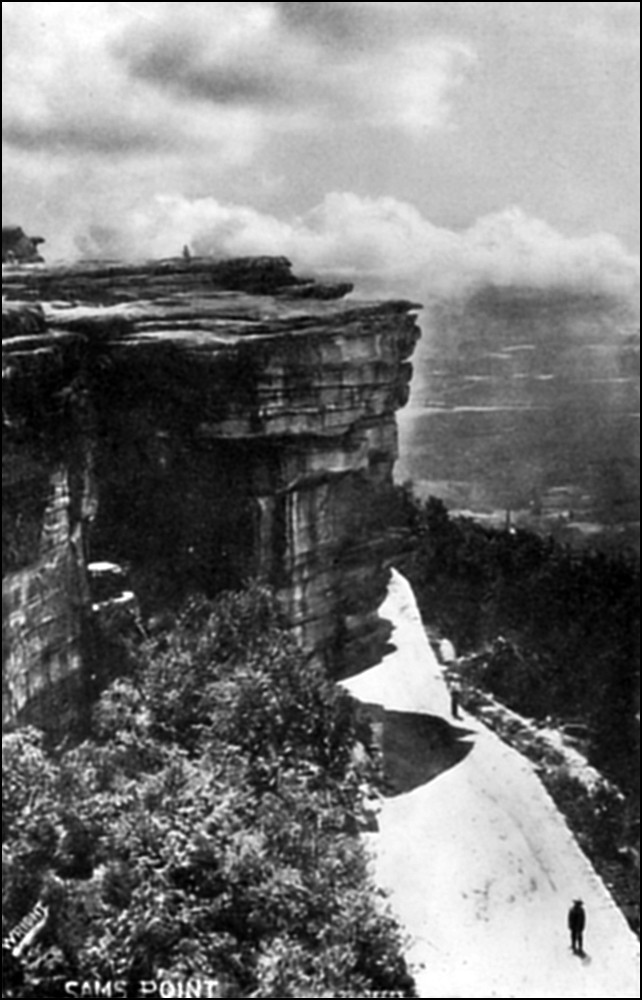

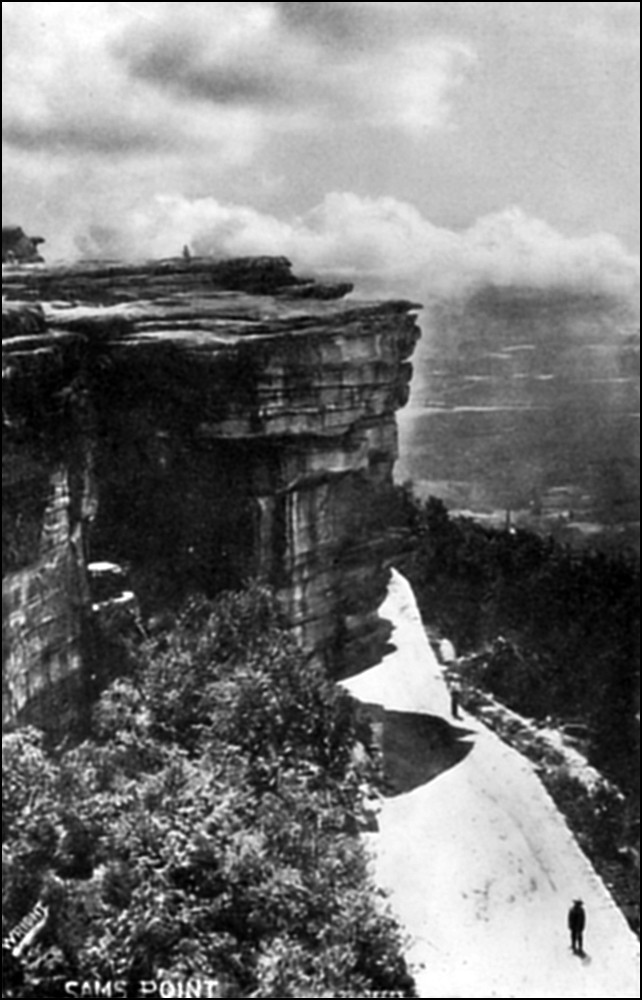

Those who have never visited Sam’s Point can have no conception of the grandeur of these rocks there piled in fantastic shapes. It needs but a little stretch of the imagination to believe one’s self among mediæval castles. One almost expects to see some plumed knight appear on the turret-like walls.

The trees are scattered, but a balsamy odor fills the air and the blending of colors makes the scene one of rare beauty.

They put out their horses and took dinner at an inn near the Point, and afterward ascended to the airy summit, where, lying down on the smooth floor of rock which appears like a plaza, they looked out on a view sublimely beautiful, aptly described by a familiar writer: “On the south the view is bounded by the mountains of New Jersey; the Highlands of the Hudson lie to the southeast; with the white sails of sloops and the smoke of steamers in Newburgh Bay, plainly visible to the naked eye; the Housatonic Mountains of Connecticut bound the horizon on the east; the whole line of the Berkshires of Massachusetts and portions of the Green Mountains of Vermont may be seen to the northeast; while the Heldebergs on the north, the Catskills and Shandaken Mountains on the northwest, the Neversink on the west complete a panorama in some respects unrivalled in America.” Down at their feet lay the historic valleys of Rondout and Wallkill.

“How did this bold promontory get its name?” inquired Dora.

“From an early settler by the name of Samuel Gonsalus,” replied Mr. De Vere. “The legend runs thus:

“He was born in the present town of Mamakating, was reared in the midst of stirring scenes of frontier life and border warfare in which he afterward took a conspicuous part and was at last laid to rest in an unassuming grave in the vicinity where occurred the events which have caused his name to be handed down with some luster in the local annals. He lived on the west side of the mountain, a locality greatly exposed to Indian outrage, and his whole life was spent in constant danger. His knowledge of the woods and his intimate acquaintance with the haunts and habits of his savage neighbors rendered his service during the French and Indian War of inestimable value. He possessed many sterling qualities, not the least among which was an abiding devotion to the cause of his country. No risk of life was too imminent, no sacrifice of his personal safety too great to deter him from the discharge of his duty.

“When the treacherous Indian neighbor planned a sudden descent on an unsuspecting settlement, Sam Consawley, as he was called, would hear rumors of the intended massacre in the air by means known only to himself, and his first act would be to carry the people warning of their danger. At other times he would join expeditions against bands of hostiles. It was on such occasions that he rendered such signal service. Though not retaining any official recognition, it was known that his voice and counsel largely controlled in the movements of the armed bodies with which he was associated, those in command yielding to his known skill and sagacity.

“His fame as a hunter and Indian fighter was not confined to the circle of his friends and associates. The savages both feared and hated him. Many a painted warrior had he sent to the Happy Hunting-grounds. Many a time had they lain in wait for him, stimulated both by revenge and by the proffer of a handsome bounty on his scalp, but he was always too wary for even the wily Indian.

“In September, 1753, a scalping party of Indians made a descent into the country east of the Shawangunks. The warriors were from the Delaware and had crossed by the old Indian trail leading through the mountain paths known as ‘The Traps.’ Their depredations in the valley having alarmed the people, they were returning by this trail, closely pursued by a large body from the settlements. At the summit of the mountain, the party surprised Sam who was hunting by himself.

“As soon as the savages saw him, they gave a warwhoop and started in pursuit. Now was an opportunity, thought they, to satisfy their thirst for revenge. Sam was a man of great physical strength and a fleet runner. Very few of the savages could outstrip him in an even race, but the Indians were between him and the open country and the only way left was toward the precipice. He knew all the paths better than did his pursuers and he had already devised a plan of escape while his enemies were calculating on effecting his capture, or his throwing himself from the precipice to avoid a more horrible death at their hands. He ran directly to the Point and pausing shouted defiance at his pursuers, and leaped from a cliff over forty feet in height. As he expected, his fall was broken by a clump of hemlocks into the thick foliage of which he had directed his jump. He escaped with only a few slight bruises. The Indians came to the cliff but could see nothing of their enemy, and supposing him to have been mutilated and killed among the rocks and being themselves too closely pursued to admit of delay in searching for a way down to the foot of the ledge, they resumed their flight, satisfied that they were rid of him. But Sam was not dead as some of them afterwards found to their sorrow. To commemorate this exploit and also to bestow some form of recognition of his numerous services, this precipice was named ‘Sam’s Point.’”

Sam’s Point

Dora shivered as she looked down into the abyss below, into the veritable clump of hemlocks where Sam landed; but Jack recalled her to herself: “If we are to take in Lake Maratanza we’d better get a start on.”

“Lake Maratanza!” she exclaimed. “Up here among the clouds?”

“Yes,” he returned, “and it is the least beautiful of four lakes running along the summit of the mountain,—Maratanza, Awosting, Minnewaska and Mohonk.”

A brisk half-mile walk over the pavement-like rocks bordered with huckleberry bushes and stunted pines brought them to the lake, a beautiful sheet of pure, soft water whose surface was rippling in the slight breeze and sparkling with innumerable gems in the brilliant sunlight.

Dora was lost in wonder—“Where does the water come from?”

“Some time ago at a meeting of scientists that very question came up for discussion but no definite conclusion was arrived at,” said Mr. De Vere. “In my opinion it comes from drainage. The lake lies in a depression and on three sides the shores are composed of shelving rock which slopes toward the lake. These rocks are thickly covered with moss and bushes and the moss absorbs all moisture falling on it, and, as the evaporation is slight, it gradually drains into the lake. To substantiate this, the one shore which is more depressed forms an outlet for the water after it has risen to a certain height and from which issues a gurgling brook. In times of drought the water recedes and the brook ceases to flow.”

“Maratanza” she mused, “another of your beautiful Indian names.”

“Yes,” replied Mr. De Vere, “Lake Maratanza was recorded as such in the old capital of Ulster County over one hundred years ago, and derived its name from a Delaware squaw who, with her little papoose, was drifting idly over the surface of the lake in a birch-bark canoe when the first white man came to its shores. Suddenly her dark-eyed mate concealed among the bushes near cried out: ‘Maratanza, white man’s come!’

“‘Indian ghosts are all about us,

And ’tis whispered ’mong the pines:

Maratanza’s shade still wanders

O’er the lake in cloudy lines.’”

“Allow me to present you with the first huckleberries of the season, Dora,” said Hernando, handing her a sprig of fully ripened berries. “Shawangunk berries are famous.”

“Huckleberries? I have never tasted one. They are delicious,” Dora replied.

“Just wait till you taste Margaret’s huckleberry cobblers!” said Jack; “m, m——it makes my mouth water to think of it!”

But the sun was getting low and even now the shadows were beginning to creep up the mountains so they reluctantly turned away from the lake.

Before they arrived at the inn where their conveyances were, the sun had gone down behind old Neversink, leaving one of those gorgeous June plays of color seen only in mountainous regions. Slowly the mountains became purple, then gray in the soft twilight, and gradually faded from view altogether. Soon the din of active life reached the ear and they emerged onto the Berm.

All were greatly affected by the events of the day and each communed with himself. To Dora, it was the event of her life. She felt lifted out of the prosaic ruts onto a more exalted plane.

Margaret had supper waiting for them when they reached home and it was duly disposed of by the hungry party. Mr. and Mrs. De Vere retired soon after and thinking her absence would be unnoticed, Eletheer stole away to her private study and was so deeply absorbed in her work that she did not hear a light tap on her door.

“May I come in?” said Hernando.

“Certainly,” she replied, opening wide the door.

They sat before the open window and she laid aside her book, turning cheerily toward him.

“Eletheer,” he said, “I believe you graduate next year. Does that mean that your future work is mapped out?”

“I think so,” she replied earnestly. “The ambition of my life has been and is to become a trained nurse.”

“Following one’s vocation should, and does, bring success. Dr. Herschel feels confident that you are on the right trail and that training will develop an inherited talent for nursing.”

“A high compliment truly, and one that I appreciate. Nursing is, indeed, a sacred calling, a calling that requires rare gifts; but I sometimes wonder if all nurses fully appreciate its true significance. It surely does not mean that we have forsaken the world and all its pleasures for the sweet joy of ministering to the afflicted, in other words, that the woman is wholly absorbed in the nurse. I see the force of Dr. Herschel’s argument which is, that nursing is neither an order, a trade, nor a means of earning a livelihood; but that it must ultimate in a profession filled almost exclusively by women. Our American hospitals, though second only to those of England in point of equipment for the training of nurses, are still imperfect. From a small beginning actuated by humane motives, of necessity, nursing has assumed vast proportions. Like all other avenues of human activity, the bad crops out with the good and many a conscientious nurse suffers for the sins of one who has crept in. Then, too, expert training is a necessity. Now a good registration law would materially lessen many existing evils. Any nurse who has earned the right to affix ‘R. N.’ to her name would be known as one who had met the requirements of such law and was legally responsible thereto.

“‘New occasions teach new duties,

Time makes ancient good uncouth;

We must upward still and onward,

Who would keep abreast of truth.’”

“True,” replied Hernando, “these are the days of expert training. The doctor’s assistant must keep his pace but I am sure you will agree with me that while nineteenth century conditions may teach nurses ‘new duties,’ it behooves them all to remember that their distinctly feminine attributes, gentleness, tenderness, sympathy, may still be retained and yet keep ‘abreast of truth.’”

“Yes, indeed; we might learn a lesson from Reuben. He and his race are the ‘natural nurses.’”

“And through the sympathy which nurses only can give, they touch the chord which even a mother cannot reach. Dr. Herschel’s discovery is the marvel of the age; but I know that without Reuben’s help, my case would have been a failure.”

“Sometimes,” said Eletheer hesitatingly, “I think that Reuben possesses the ‘sixth sense.’”

“Reuben is one of those rare characters ‘we read of,’” replied Hernando.

They heard the back stairway door open, close, and then Reuben’s measured tread up the back stairs. As he was passing Eletheer’s door on his evening rounds both she and Hernando called to him to join them.

“Law me, chillen,” he said with beaming eyes, “I’se po’ful glad to see you togetha once mo’.”

“And,” said Eletheer with her old impetuosity, “Hernando feels that but for you, one of our number would be missing.”

Reuben looked reprovingly at her, and Hernando added:

“I do in very truth, my friend. I know that your prayers in my behalf are answered.”

“Yes, Massa, an’ I know it too. De good Lord allus ansus ’em. Yo’ know what de Good Book says,—‘Ask an’ yo’ shall receive.’”

“I know that,” said Eletheer, “but on one condition only are our prayers to be answered, and that is an unreasonable one: ‘Believe that you have received it.’”

“Ob co’se, Honey; but to my way ob t’inkin’ dat am a bery reasonable condishun, we hab ‘received it.’ De good Lawd done finished His work. Yo’ see, Honey, de p’int am jes’ hyah,—we’se sunk in trespass an’ sin, got blin’ eyes an’ deaf ea’s. What’s de sense in pleadin’ an’ coaxin’ de good Lawd to give us a lot ob t’ings when we aint usin’ what we’s got?”

“Then,” said Eletheer, “when you asked God to cure Hernando, you honestly and truly believed that He would do it?”

“Sho’s yo’ bo’n I did, Honey.”

“I know you did, Reuben, and ‘without a doubt in your heart,’” said Hernando.

“Ob co’se; an’ along comes Doctah Herschel!”

“You blessed old Reuben!” said Eletheer, giving his arm a squeeze. “I believe you can do anything; but wouldn’t Dr. Herschel have come anyway?”

“Dat am ezackly de p’int, Honey. De good Lawd already done His part. He done gib Doctah Herschel de talent an’ de wisdom to go sperimentin’ an’ projeckin’ wif dat bery ge’m till he found a cuah in ‘Old Ninety-Nine’s’ will. Yes, Honey, he was bo’n fo’ dis bery place and de good Lawd sent him.”

“You mean, Reuben,” said Hernando, “that our every need is met.”

“Yes, Massa, when we’se willin’!”

“I agree with you,” Hernando added, “and it is becoming more and more clear what I have been in training for: Dr. Herschel proposes founding a hospital for lepers at Hong Kong. It will need intelligent supervision and my own case, together with a knowledge of Chinese acquired at Shushan, seems to have fitted me for just that work.”

“It do look as if yo’d been specially ’lected to dat mission. De flesh-pots ob Egypt don’t tempt yo’ no mo’; de Red Sea am behin’ yo’ an’ yo’ ken show dem po’ heathens by pussunel ’sperience dat de desert an’ mountains am jes’ dis side ob de Promised Lan’; but, Massa,” here Reuben’s voice vibrated like a deep-toned bell, “de good Lawd wants His chillen to be happy, to be de’ bery bestest selbes. He done made eberyt’ing good jes’ a pu’pose fo’ dem to use. De Good Book says,—‘Happy am de man dat findeth wisdom, an’ de man dat getteth undastandin’’—‘All huh ways am ways ob pleasantness, an’ all huh paths am peace.’ Yo’se plumb kuahed now, got back to de fo’cks ob de road an’ de’s on’y two, de right one an’ de wrong one; an’ onless de one p’intin’ to Hong Kong ansahs de call f’um de bery bottom ob yo’ hea’t, onless dat ansah comes so natrel-like dat it don’t take no strainin’ to go, yo’ won’t fin’ wisdom dat-away an’ it aint de path ob peace.” After a pause he resumed: “I reckon dat strainin’ am f’um de Debbil. Hit makes sich a roarin’ in de ea’s dat we can’t heah de ‘still small voice’ allus a-tellin’ de truf. Yes,” he concluded, “dat’s strainin’ an’ de p’int.”

Hernando gave an imperceptible start. “Cured.” Yes, he was cured, had the right to a place beside other men in this world of affairs. A right good old world it was, too, with its triumphs and defeats, its joys and its sorrows, its “marryings and giving in marriage!” “Cured!” What hopes that word awoke in him, thrilling him with a sweetness that defied analysis. Had the wise man really found wisdom, and were all her ways “ways of pleasantness and all her paths peace”? Why, oh, why did this old world of unrest, of human desires still call to him! Had he not renounced it that he might win a better? Surely it could have no claims on him now. Yet a wave almost of resentment surged over him at the thought.

“Massa!”

Hernando turned absently toward his questioner and did not notice that Eletheer’s chair was empty.

Reuben waited a few seconds and then said softly,—“Massa, we can’t take de Kingdom of Hebben by sto’m.”

“You’re right, of course, Reuben,” Hernando answered, giving himself a mental shake. “I’m afraid I’m a poor soldier anyway.”

“’Scuse me, Massa, mebbe yo’se done been fightin’ undah de wrong Cap’n; an’ mebbe agin taint no use fightin’ nohow; jes’ let de Kingdom ob Hebben take yo’.”

Hernando leaned slightly nearer, and Reuben went on,—“Now taint no makin’ b’lieve ’bout dis gibin’ up, like dem po’ sinnahs what hollahs amen, ’thout takin’ de mo’nah’s bench. Hit’s got ’o be a willin’ sacrifice. We mus’ git right down on our knees an’ hollah f’um de bery bottom ob de hea’t,—‘Oh, Lawdy, Lawdy, hyah am eberyt’ing I got in dis wo’l ’thout no stipylations!’ Den we mus’ trus’ de good Lawd an’ be glad to trabel back to de fo’cks of de road; an’ w’en dis trablin’ do seem like hit aint neber goin’ to en’, we must ’member de promise: ‘God am a bery present frien’ in time ob need.’”

Hernando’s face twitched as he looked at Reuben. What did he see? An old black man? The vision belonged to Hernando alone; he seemed to hear a clock strike “I! II!” Hear the soft crackle of dying embers on the hearth in a room filled with shadows, feel a trembling old hand press his own in sympathy while they two “made sacrifice.” Was his sacrifice “willing,” was he glad to go to Shushan and had he remembered the “promise”? And yet in those six years he thought he had “worked out” his “own salvation,” found the secret of happiness, sounded the doctrine of trust, drawn the specifications for a useful life in which the old world had no part. Yes, only thought; for that old world kept calling, calling—and oh it was like sweet music in his ears!

“Just let the Kingdom of Heaven take you.”

What else had he been doing for years, Hernando thought.

“Have you submitted those specifications?”

The voice sounded so near that Hernando looked quickly at Reuben; but apparently he had not moved a muscle since his last remark. Whence came that voice? All else was still; even the rustling leaves outside seemed to wait like the enchanted fairies, for his answer, while that relentless question dinned in his ears.

“Have you submitted those specifications?”

Yes, had he? Hernando’s tension relaxed somewhat at the admission of an honest doubt, and the dinning in his ears grew fainter before the incoming light. Alas! no, the Bar of Justice before whom all plans must go had not passed on his. The dinning in his ears ceased; and then something, that Something which comes to each of us when self is melted into the sincere desire for truth for truth’s sake, flashed upon him. Only a flash, a glimpse of the real; but Hernando caught it, saw that his message had been received, knew that at the right time, and in the best way, the call from the very bottom of his heart would be answered.