CHAPTER XIV

IF one cloud dimmed the happiness of the De Vere household on the following morning, it was too small to be seen. Reuben awoke with the birds and from the chicken yard ominous squawks foretold what would constitute one item in the bill-of-fare for breakfast. “Molly,” Cornelia’s Jersey cow, was poking her nose through the bars ready to contribute a generous supply of rich milk, and soon afterward Margaret’s “Co, boss!” made her step lightly aside while with shining pail that worthy woman lowered the bars and entered the barnyard.

“Oh, Reuben!” she shouted, “what yo’ doin’ to dem chickens? I ’clare to goodness, yo’ll drive me plumb crazy.”

“Nebba yo’ min’ dem chickens! Yo’ jes’ pay ’tention to Molly.”

He appeared just then around the corner of the barn with three headless chickens, and as his wife’s glance fell on them, she exclaimed, with uplifted hands,—“Fo’ de lan’ sake, ef yo’ aint done gone an’ killt de baby’s dominick pullet!”

Reuben’s crest-fallen countenance softened her heart, however, and she said no more and was soon on a stool beside Molly. Did she miss old associates in the sunny South? If so, no one knew it; as with Reuben, Massa John and Miss Bessie’s world was hers, and had they gone to the wilds of Siberia, these two faithful servants would have followed and been content.

Cornelia’s face sparkling with perfect health just then peeped out of the kitchen door. She was going “after an appetite,” she declared, and skipping past Margaret was soon climbing to a point beyond and above the barn. Reuben’s heart smote him as he thought of the “dominick pullet,” and he called out to the fast vanishing figure,—“Oh, Miss Cornelia, don’t yo’ forget Molly’s salt!”

She threw back a laughing glance and ran her hand into her pocket, a motion he understood, and disappeared from view. She was passionately fond of animals and particularly of horses. Reuben often declared, “Dat chile aint afraid of nuffin on fo’ legs.” She certainly understood and loved them and was an accomplished horsewoman; but this morning her visit to the barn was a short one and, turning a sharp angle in the path, her blue dress fluttered in and out among the bushes as she wandered away upward.

Unseen by her, from a projecting rock above, a pair of eyes as blue as her dress was watching her, as she sprang from rock to rock, every motion perfect grace. Pausing, she glanced upward and saw Hernando.

“Well,” she laughed, “what brings you out so early?”

“‘Great minds run in the same channel,’ doubtless I am hunting for the same thing you are.”

“A bath in the morning dew?”

“You certainly do not need one, and I am looking for a very prosaic article, known as an ‘appetite.’”

“I’m pretty well drabbled,” she said demurely, not noticing his look of admiration. “But come, I’m not like Eletheer, Mr. Gallant, help me to a seat up there beside you.”

He was already preparing to do so and, taking off his coat, he spread it on the rock, which was still damp with dew, and they sat down together.

It was not yet seven, the busy city below them had not yet fully wakened and the air was fresh and sweet. To Hernando, the girl beside him had always been simply “Cornelia, the baby.” Like Eletheer, he too had noticed George Van Tine’s marked attentions to her but he had also noticed that they were not objectionable, and he wondered if she fully understood the seriousness of marriage. Just now she was looking intently down among the rocks and bushes and he said gently,—“‘A penny for your thoughts.’”

“I’m just wondering if my guineas could have stolen their nest in that thicket,” she answered, pointing to where her glance had been directed.

Restraining a laugh, he asked,—“Are they up to that sort of thing?”

“Up to it? Well I should say so. They deliberately hide them, and are noted for their bad behavior in that line. Mine have completely eluded discovery. But I love them, though Eletheer says their cry reminds her of a rusty pump.”

What could he say to this child, and how assist Eletheer in her sisterly efforts in what she believed her duty? As Eletheer said, Cornelia was indeed gifted with an unusual voice which might bring fame. She also was “young to make a choice which might be regretted later.” “But after all,” he thought, “these matters are better let alone when there is nothing radically wrong, and I see nothing in this case.” Why break the spell which held her a willing captive? To what nobler use could her voice be put than bringing sweet sounds into a good man’s home where, surrounded by husband and children, she would be shielded from temptation? Surely in that, she could find nothing to regret.

He glanced toward the hills among which lay Shushan, where the last six years of his own life had been spent, and his mind reverted back to that awful night of his banishment when life seemed a mockery and annihilation a bliss. Further back still, he sees a kind old face crowned with silvery hair and tears of pity filling her eyes. “Dear old granny,” he thought, “your prayer for mercy is answered; and though we may view things differently, we look in the same direction.”

The city was stirring now and the busy hum of life had begun. Whistles from the factories and mills were calling to work. Seven o’clock, and the distant screech of a locomotive told of the nearing of Ulster Express.

“I feel it in my bones that we’ll have company for breakfast,” said Cornelia, rising and standing on tip-toe to see how many passengers got off. Cornelia’s “feelings” were a family joke, but Hernando also arose and looked down the road, more to keep his companion from falling than from any expectancy of “company for breakfast.”

The station was in plain sight and as they turned their heads in that direction, a very singular-looking passenger jumped from the train, satchel in hand, clearing the steps at a bound. He was clad in a hickory shirt, blue jean trousers and brogans. On his head was a broad-brimmed, soft felt hat. Apparently he stopped to question one of the station men for the latter pointed toward the mountain and he started up that way.

“Who on earth can he be!” said Cornelia, clapping her hands in excitement.

“He looks and walks like a cowboy,” replied Hernando. “Come, let’s go down. This time, at least, your presentiment seems a true one.”

But for Hernando’s restraining hand, she would have jumped from the rock on which they were sitting; by dint of engineering, however, he kept her within bounds until they reached the back yard, when she started for the house on a keen run. Rushing past Margaret, whose hands were uplifted in disgust, she burst into the dining-room with cheeks that vied with the roses on the breakfast table.

——“And this, Mr. Watson, is our daughter Cornelia,” said Mr. De Vere, laying his hand on her shoulder.

Like Jack, Cornelia was instantly won. All she saw was those same honest blue eyes and though his grip made her knuckle-bones ache, she bore it without flinching. His admiring glance made her cheeks rosier than ever.

“Now that you have seen us all, I am aware of an uneasy sensation in that region of my anatomy known as the stomach, and Margaret’s coffee smells mighty good. Shall we sample it?” said Jack, and without more ceremony they sat down to breakfast.

Contrary to her usual custom, Cornelia remained silent. She glanced uneasily towards the door and finally, unable longer to keep quiet, said, “I wonder what keeps Hernando?”

“Sure enough where is he? How thoughtless we are!” Mrs. De Vere answered, rising and starting towards the hall. “Ah, here you are, Mr. Truant,” she laughed, as the door at that moment opened. “Come and meet an old friend!”

“An ever friend,” he corrected, advancing toward Watson with extended hand.

The latter grasped it with a true Texan grip but his expression of sympathy gave place to one of amazement as he looked into that pure face. No marks of resentment or disease there, only an expression of absolute self-forgetfulness and charity for the weaknesses of others.

Watson’s vindictive feelings toward Mills faded away. Such were out of place here and his customary “doggone it” escaped without his knowing exactly why.

The bright morning sunlight streamed into the room as if to accentuate the happy faces around the breakfast-table. Watson, to all but Margaret, seemed to have simply dropped into his place. Her feelings were beyond analysis but she confidentially whispered to Reuben as she returned to the kitchen to get more hot muffins, “He aint no kwolty.”

Many were the questions to be asked and answered and in consequence, it was nearly nine o’clock before breakfast was over; then Watson found himself the center of an admiring group. First of all, he was buttonholed by Jack and his laugh, hearty as the winds of his own State, made the walls ring, and all involuntarily joined.

“You ought to be a very happy man, Mr. De Vere,” he said, addressing the latter.

“I am,” Mr. De Vere replied. “Only a few years ago this beautiful city was a mere hamlet. The wonderful resources of this valley were undeveloped and no prospect of better conditions.”

He looked musingly in the direction of the mine. “Hernando came to us and proved ‘Old Ninety-Nine’ no myth—of course you know the history?” Mr. De Vere interjected.

“Yes, and Jack tells me you have in your possession one of his ears, petrified.”

“Had,” corrected Mr. De Vere, “but no curious eyes shall scrutinize what should not be an object of curiosity. Dr. Herschel pronounced it the ear of a leper, so I destroyed the poor deformed member, and the statue of ‘Old Ninety-Nine’ soon to be unveiled in Delaware Park, is such as he must have been in his prime. You must get Hernando to tell you of his life at Shushan.”

“Does he speak of it?” Watson inquired aghast. “I’ve been afraid I’d let something slip. Poor boy, poor boy!”

“Poor boy, indeed!” Jack retorted. “Why, Watson, he loves to, and the rugged hills of Shushan are to him the most beautiful spot on earth.”

“His face haunts me,” said Watson. “Does he ever say anything about Mills?”

“Often, and always with compassion.”

Watson was silent, and just then Cornelia came into the room and dragged him off to inspect her horse, as Jack had told her of his reputation as a judge of horseflesh. He went willingly enough, for his ideas on the subject under discussion were not quite clear, and he also felt a trifle elated at the prospects of showing off the good points of a horse to such an attractive listener. They could not have more than reached the barn, when Mr. Genung was announced.

Evidently he was in ignorance of Watson’s arrival; had simply “dropped in” on his way to the mine where, as one of the largest stock-holders, his influence was felt. Although unpopular with the miners, all admitted him to be just according to his convictions and his advice sound. Hernando’s trouble had aged him greatly. His once black hair was thickly strewn with grey and after the greetings were over, he sank into a chair quite exhausted. Eletheer slipped unobserved from the room and shortly returned with a cup of coffee, well knowing Mr. Genung’s weakness. He accepted it gratefully, saying, “Ah, my dear, you have chosen the right profession!”

“If all my duties were to be as pleasant as this, I have certainly selected an easy one,” she laughed.

“By the way,” he said, “I am the bearer of a message from Dr. Brinton to you. He was driving like mad up Lombardy Street, but seeing my direction, I presume, halted long enough to say that he would like to have you call at his office this afternoon. Dr. Herschel was with him. Now,” handing her the empty cup, “I have delivered the message, and you may refer him to me for recommendation.”

Conversation drifted into generalities and Eletheer went to help her mother in household duties.

Eletheer was not given to presentiments, but the mention of Dr. Herschel’s name made her shiver. She always thought of him in connection with that awful night of Hernando’s departure for Shushan and could barely restrain her excitement at the thought of meeting him for, in her eyes, he was all-powerful. “Ridiculous,” she thought, giving herself a mental shake. “I’m a goose to be nervous, and very likely he is not in any way concerned with Dr. Brinton’s message to me.”

Her hands and feet kept time with her busy brain and long before noon no trace of disorder was to be seen. As Mrs. De Vere often lamented, she was not “like other girls.” Generous to a fault and charitable toward her friends, yet, like Granny, she would not tolerate weakness nor a deviation from her standard of right.

During her grandmother’s lifetime, her religious training was strictly in accordance with the teachings of the Reformed Dutch Church. The Bible, including punctuation marks, she had been taught to regard as a direct revelation from God and her childish doubts were sternly rebuked. After the old lady’s death, other influences crept in and association with people of expanded minds created a tumult in her naturally analytical brain. But the first impression was too deep to be completely obliterated, and though she could not conscientiously become a member of the church in whose doctrine she had been so thoroughly grounded, any imputation that her belief in it was weak was resented until obliged to admit that it was true, and even then she recoiled from the thought. Hernando’s troubles stirred the smouldering fires anew, and later from her experience among suffering humanity at the training school, where the physicians and surgeons, and in fact the entire hospital staff, were decidedly unorthodox, she was obliged to say when asked her belief, “I don’t know.” To try to do right and let the future take care of itself became her creed and she accepted it, knowing no better.

Two o’clock, Dr. Brinton’s office hour, came at last and, in a flutter of excitement, Eletheer hurried through the busy streets toward his office. She had not long to wait, for, though the reception-room was full, on receiving her card Dr. Brinton ushered her into his private office where who should advance to meet her but Dr. Herschel. Evidently the appointment was with him for Dr. Brinton had disappeared.

“What can Dr. Herschel want of me!” Eletheer thought, nervously taking the nearest seat. Her doubts, however, were soon dispelled; as, drawing from his pocket a formidable-looking document, Dr. Herschel said,—“This is ‘Old Ninety-Nine’s’ will—for such it is to all intents and purposes—written in Spanish as you see. You know its history but not its entire contents; however, as you are practically in the profession, a full understanding of the will may have an added interest as it shows what advances have been made along bacteriological lines and, I might add, clearly illustrates the influence of mind over matter.

“After ‘Old Ninety-Nine’s’ cure, he continued to live at Shushan, making occasional trips to his cave, the whereabouts of which were sacredly guarded from discovery—indeed this document is so carefully worded as to give not a hint of its locality. While at Shushan, many years after having been cured, he had another revelation in the form of a dream. He must fly to his cave or evil spirits would obsess him for they were powerful, and after this sickness he might not be able to resist them.”

Here the doctor paused and looked searchingly at his listener but, seeing only an expression of interest on her face, went on,—“The old chief hastened to his cave, though not with the vigor of youth, only to find evil spirits in possession. Putting this document—which in reality is not a will—no Indian ever makes a will—with his other treasures into the chest he securely locked it and implored the Great Spirit to lead him to the Happy Hunting-ground. We can trace him no further, even the events last narrated are merely inferences from circumstances. We know that he went to the West Indies and I infer from collateral facts that he had a Spanish wife who suggested and formulated this document. His sudden and obscure death deprived her of any knowledge of the fact.” Dr. Herschel carefully folded the document and, leaning back in his chair, lit a cigar.

“Was he insane?” Eletheer asked.

“Insanity is a nice word to define. ‘Old Ninety-Nine’ was not insane, but died in an hysterical seizure. This would explain finding his body in that dangerous place.”

“Then he did not believe himself cured?” Eletheer said.

“Have you yet taken up the study of the nervous system?” Dr. Herschel asked, as though what had happened were an every-day occurrence.

“No, that comes in our second year.”

“One year on the nervous system! Ten years, a lifetime; and we are still in an unexplored realm.

“I wish particularly to point a moral in ‘Old Ninety-Nine’s’ case, as the symptoms there manifested will be among the most difficult to treat, particularly in the uneducated. First, because the word leprosy is crystalized in the human mind into an incurable disease and having once had it, a patient, unless of unusual intellect, lives in constant dread of its return—our hospitals for the insane would grow beautifully less by the elimination of that one element fear. Leprosy is a germ disease; the leper bacillus was discovered in 1874. Thus heredity is disproven. We know it to be a parasitic disease.”

“Then children of leprous parents cannot inherit the disease?”

“No, except a possible predisposition. This does not mean, however, that I advocate marriage between lepers. If children are born of such parentage, they ordinarily die young or are a prey to every disease. The point I wish to illustrate is that nervousness is the worst tyrant of the day. True, ‘Old Ninety-Nine’ was already an old man; but he might have lived many years longer only for fear, which, combined with his racial traits, made a formidable enemy indeed.

“This is a question of great importance to nurses, one with which they, more than the physician, will have to contend. A nurse is sent on a case, possibly diphtheria, one of the most fatal diseases known. When we discover the germ a cure must follow and, as in any germ disease, corresponding nervous symptoms follow from destruction of tissue. Strange!” Dr. Herschel said, looking towards Shushan, “the many discoveries now being made on the physical plane, yet they do not unlock the doors to the spiritual realm.”

“Hernando claims that they do,” said Eletheer.

This happened to be one of the rare occasions on which Dr. Herschel laughed; and he did laugh with a right good will. “Yes,” he said with a twinkle in his eyes, “Hernando explained his philosophy to me at some length during the last year of his stay at Shushan. As I understand him he believes that thought, like electricity and magnetism, is a force, and that it may be intelligently applied in the treatment of disease. Of course he refers to diseases of nervous origin, such as hysteria and some allied functional disorders, and in this he is quite right; but, Miss De Vere, my experience has been on other than metaphysical lines. As a nurse, yours will be also. This physical body and the material world it inhabits are our materials to work with and, at this stage of evolution at least, fate must be reckoned with. Don’t muddle your brain with these new sciences and cures. Keep on solid ground.

“Now Hernando is a splendid fellow, an ideal patient, and while I agree with him that the greater part of human ills are largely imaginary, and that it is natural for vegetable and animal life to grow from darkness to light, I am also grateful for the knowledge—and its results—revealed to us by microscopic vision into the world of micro-organisms. This is something tangible.” And rising, Dr. Herschel indicated that the interview was over.

After Eletheer left, Dr. Herschel walked rapidly back and forth, stopping occasionally to look out of first one window and then another; but the objects he saw were visible only to him. One thing he intended to do and that was to keep this girl in sight. She was possessed of the qualifications necessary for the making of an ideal nurse—a trifle visionary, perhaps; but experience would cure that—and it should be his duty to see that her aspirations in that line were realized as nearly as lay in his power. Another year at the training school would do much, and then he would do the rest.

All unconscious of these plans for her future, the object of them sped homeward. Turning a corner sharply she almost ran into Mary Genung and the latter laughingly called,—“Eletheer De Vere, do you mean that as a cut direct?”

“Certainly not, Mary, I confess to absent-mindedness. Come along home with me.”

“I’ve just been there. Your mother told me that you were at Dr. Brinton’s and that I might meet you. Let’s go after rhododendrons in the paper-mill woods. Please don’t refuse.”

“I’ve no such intention,” laughed Eletheer as she followed her companion to where, as children, they had spent many, many happy hours together. How long ago that seemed now—and she listened mechanically while her friend pointed out critically the architectural beauty of several newly erected buildings. They were passing the old Reformed Dutch Church when Mary exclaimed,—“To my mind, no structure in the city can approach this. In its chaste Corinthian lines, it is indeed a fitting monument to the religious zeal of our ancestors.”

“Is it not Emerson who says that all men are at heart religious?” Eletheer answered.

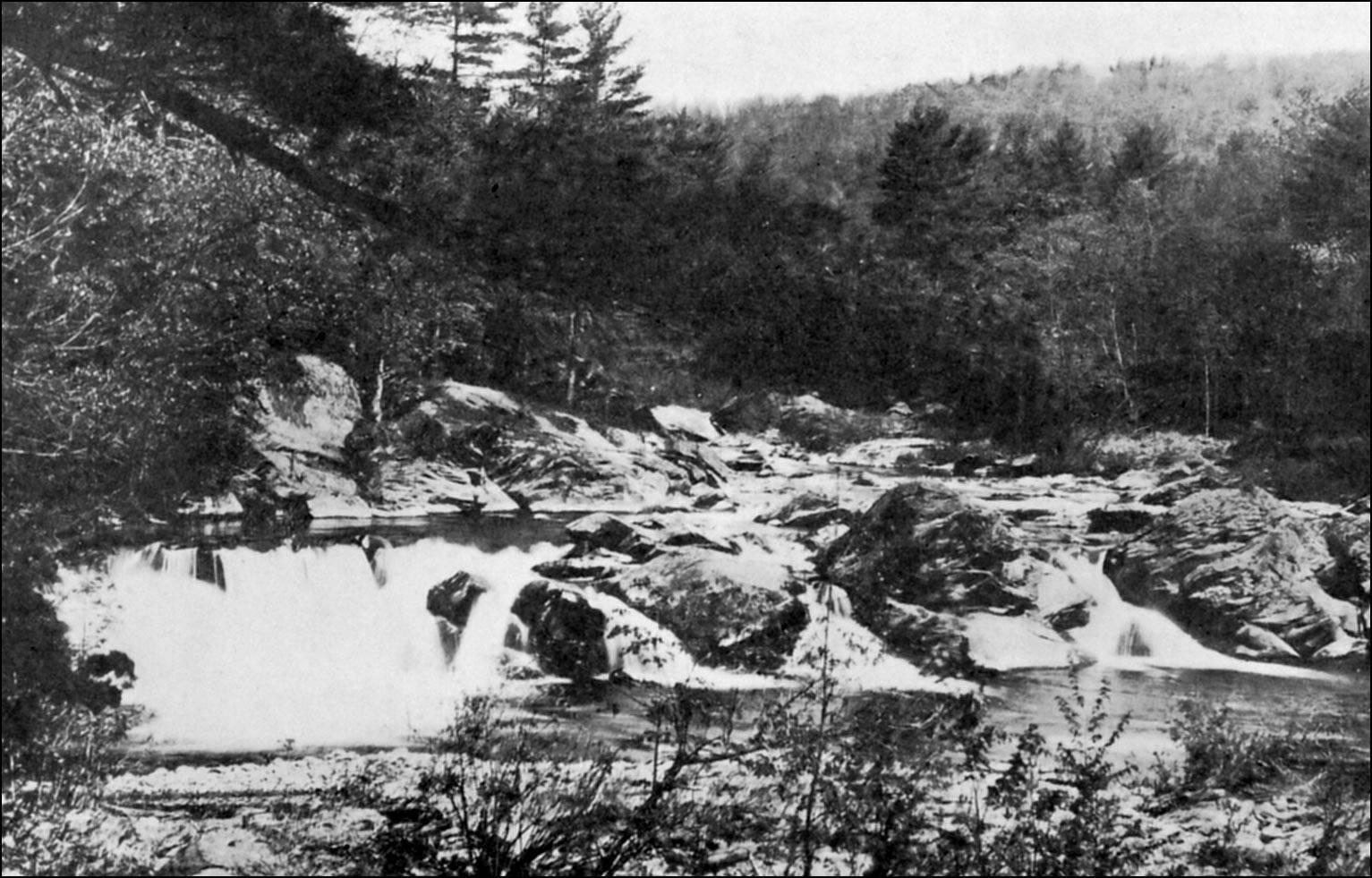

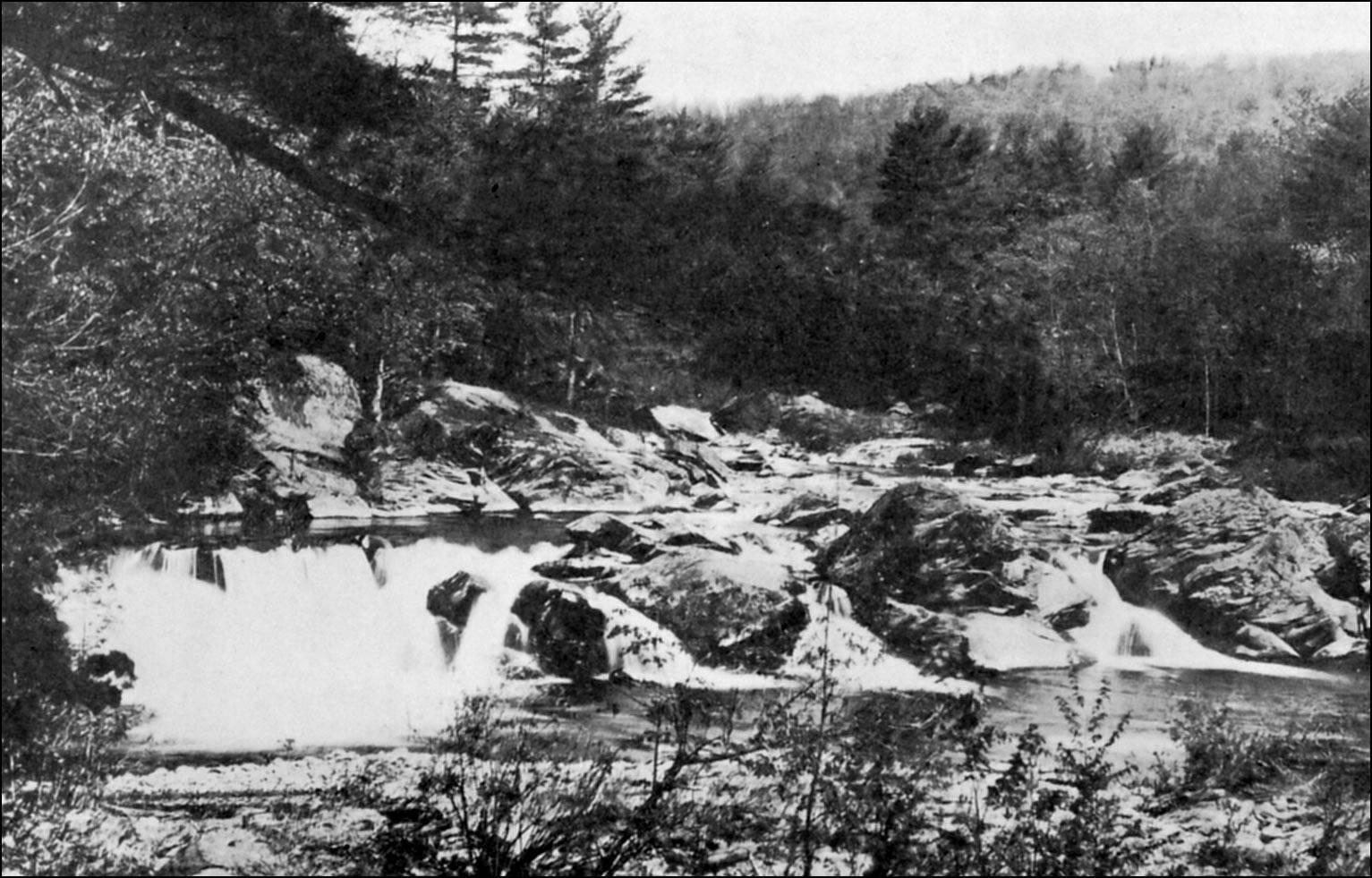

Mary made no reply, and they were soon climbing the steep, rocky incline near the entrance to the woods. It was known as the “Old Honk Falls’ path.” The day was excessively warm and strangely quiet. The Rondout creek tumbled musically over the rocks below, forming many beautiful cascades, and the girls stopped occasionally at some bend in the stream to watch the myriads of brilliant-hued dragon-flies glinting through the branches of some fallen tree; but in the oppressive afternoon heat even the birds seemed seeking a covert. The girls quickened their steps and soon disappeared into the woods beyond.

“Oh!” said Mary, as she sank on the carpet of fragrant pine-needles. “Talk of the ‘murmuring pines and the hemlocks.’ I fail to detect the slightest motion in these.”

The Rondout Creek tumbled musically over the rocks below forming many beautiful cascades

“It does seem unusually quiet, and that with the heat makes me apprehensive. Reuben would say ‘it means sumfin’,’” Eletheer returned, seating herself beside her companion.

“Well,” retorted Mary, “if you know a cooler spot, I’ll gladly follow to it; but did God ever create a more beautiful one?”

It was, indeed, a spot of rare beauty; such as must have inspired the cathedral-builders of old; great pines and hemlocks reared their lofty columns upward to be there crowned with a covering so dense as to admit scarcely a ray of sunshine. A solemn arcade indeed, whose cleft pillars were bound with brown withes of wild grape-vine. A brown carpet covered the floor and in this weird semi-twilight, one almost expected to hear a solemn Te Deum echo from the crossing branches above. The day was one of unearthly stillness and there was such a downpour of heat outside that the very air seemed on fire. Even the scattered clumps of ferns and jack-in-the-pulpits hung their heads as if in exhaustion.

“Are you feeling well to-day, Eletheer? You seem so preoccupied.”

“Physically, yes; but, Mary, I’m actually nervous. Everything looks so uncanny.”

“You are accustomed to an out-of-door life and I trust have not made a mistake in your choice of profession. Hark! Did you hear anything?”

“There, Mary, you too, are nervous,” said Eletheer, forcing a laugh. “See!” pointing upward, “nothing but a pair of stray bats.”

“And a snake coiled among the bushes yonder! Come, Eletheer, let’s go home. I’m getting the ‘creeps.’”

“Indeed, let’s do no such thing! It’s the heat combined with this utter silence that affects us. There goes that snake now!”

As they looked, a dirty-green snake trailed his lazy length towards the creek. At the same time, two bats fluttered over it like shadows, until they, too, melted into the tremulous haze that overhung everything.

“I was about to add,” Eletheer resumed with a backward glance, “that Dr. Herschel has been giving me some points on nerves. Now is a good time to put them into practice.”

“Well,” returned her friend, “if you can stand it I can, and that reminds me, father and I were talking of Hernando this morning. Now that he is cured, we hope that he will marry and settle down in a home of his own. As you know, he is the last male of our name and, unless he does marry, the name dies with him,” and Miss Genung looked searchingly at her friend.

Eletheer smiled as she replied,—“I can’t imagine a woman just like his wife ought to be. Honestly, now, can you, Mary?”

“Oh, Eletheer, can’t you trust a life-long friend?” said Mary in a tone of such genuine feeling that Eletheer was startled. Gradually, however, the import of her friend’s words dawned upon her and with a troubled expression she said gently:

“Mary, we are indeed life-long friends so don’t misunderstand me—you will, however. Your accusation cannot be met with argument; but there are men and women who mentally complement each other but to whom marriage, with its obligations, does not appeal.”

“I have read of such attachments,” returned Mary dryly,—“but in my limited experience they invariably end in something deeper than friendship. No, Eletheer, you may deceive yourself but not others.”

What could Eletheer say? Experience had taught her the folly of argument with this sweet little blue-eyed, Dutch-French friend, so she said coaxingly,—“Never mind that now, dear. Tell me of your proposed trip abroad next fall.”

“There is little to tell. I hope, of course, to visit France and Holland as most of us in this valley are either French, Dutch, or a mixture of both.”

“Strange! that two nations of such widely different characteristics should have so assimilated.”

The vexed expression had disappeared from Mary’s countenance; she loved to discuss the early history, and particularly religious, of this valley, and Eletheer’s interest pleased her.

“Not necessarily so,” she returned. “They were thrown together by a common persecution. The first settlements of the town of Wawarsing were made by Huguenots and Hollanders at Nootwyck and ‘The Corners.’ The ancestors of the persons who made them had passed through fiery persecutions for conscience’s sake and had the principles of the early reformers thoroughly ingrained in their constitutions. In France, these reformers were called Huguenots, but all the early Protestants of France and Holland organized churches on similar principles, which generally were called Reformed Churches. The French have always been a people of ardent temperament and decided opinions, and religion expresses the extreme characteristic of a people.

“Discouraged by fruitless efforts to obtain religious liberty at home, the Huguenots fled from their native country in great numbers, estimated at one million of the most industrious, the most intelligent and the most moral of the French nation, who sought safety in England, Holland, Prussia, Switzerland and America, taking with them their skill in the arts and as much of their wealth as could be snatched from the destroyer, thus impoverishing France and enriching the countries to which they fled, where they found a most welcome reception.

“In Holland, the Protestants suffered a continued series of persecutions under Charles V and Philip II of Spain, beginning in 1523 and lasting to the time when religious liberty was secured under William of Orange, during which time thousands of the best citizens of Holland were cruelly murdered and tormented for conscience’s sake. The Huguenots and Hollanders, thus brought into intimate relationship by common fate and a like persecution, maintained the closest and most intimate friendship with one another, worshipping together and intermarrying.”

So utterly absorbed were the girls, that neither of them was aware of a pair of listeners, Tim Watson and Elisha, who were seated just a few feet distant on a shelving rock that overhung the creek, and they also had become oblivious of their surroundings. No one noticed the increasing murkiness of the atmosphere, nor the baleful, ominous stillness as though nature was in a vindictive mood and preparing to spring upon her victim. The dull, yellow sun was fast becoming obscured by a cloud of inky blackness and a gentle sough of the wind through the tree-tops had increased to a threatening howl. But as Mary raised her eyes and glanced toward the creek, a roar like the infernal regions let loose, followed by a vivid flash of lightning, brought the four into a realization of their danger. Like a deer, Elisha leaped toward the girls and grasping an arm of each shouted,—“Out of the woods!” Another terrific flash from the zenith to the horizon was followed by a distinctly sulphurous glow. The bolt shivered the tree under which they stood. A blazing ball plowed up the ground at their feet and all three fell in an insensible heap.

Watson’s sinewy arms carried the girls tenderly to an adjoining field and laid them on the soft grass. Returning quickly to Elisha’s assistance,—“I’ll be doggoned, if they don’t have northers here,” froze on his lips as he looked at the still form at his feet; for his practiced eye told him that no human help could avail here. However, this was no place for examination, so Elisha, too, was carried to a place beside the girls.

To any one but this Texan, the scene would have been appalling.