CHAPTER XIV.

AN ULTIMATUM.

As the morning hours passed on, the feeling of uneasiness at the Mission grew in intensity. Although Georgia’s visits to the Palace were rarely less than two hours in duration, and another hour must be allowed for the journey thither and the return, she had not been gone an hour and a half before Lady Haigh began to appear from the sick room at intervals of ten minutes, and inquire whether she had not come back yet. The men waited on the terrace, too full of anxiety to settle to any occupation, and the servants watched them furtively as they went about their duties. Whether the uneasiness was due to the Vizier’s threat, or to a feeling that the tension which had so long existed had nearly reached breaking-point, every one seemed to be conscious that there was danger in the air.

At length the shouts of running footmen at the outer gates announced an arrival of importance, and a sigh of relief broke from the watchers on the terrace. Miss Keeling had returned in safety after all, but this was the last time that she should leave the Mission unaccompanied, and confide herself to the tender mercies of the sovereign of Ethiopia and his Ministers. But the shouts were not followed by the usual sounds of the creaking open of the ponderous gates and the rush of feet into the courtyard as the litter was carried up to the steps; but only by a parleying between Ismail Bakhsh and some one outside, which was audible in the inner court owing to the loud tones in which it was conducted, although the actual words could not be distinguished. Presently a servant approached the group through the archway.

“Highness,” he said, addressing Stratford, “there are two lords outside, belonging to the King’s court, who desire to speak with the Sahibs, but they will not come inside the gate.”

“Whence this exceeding caution?” said Stratford, as he descended the steps. “They have never displayed any reluctance to come in before.”

No one replied to his observation, and he went towards the gate, the other men following him, with Lady Haigh, uninvited and unnoticed, close at their heels. One of the doors was opened as they advanced, and they found themselves face to face with their old friend, the official who had met them on their first arrival in the city, and introduced them to their present quarters. Now he looked uneasy and as though ashamed of the business on which he had come, while at his side was a hard-faced, eager man, whom the English recognised as one of Fath-ud-Din’s chief supporters among the Amirs.

“Peace be upon you!” said Stratford.

“And upon thee be peace!” was the stereotyped reply.

“Will you not enter and eat bread with us?” asked Stratford.

“My lord’s servants are commanded not to enter his house, nor yet to break bread with him and his young men,” returned the official, “for their errand demands haste. Is the gracious lord, the Queen of England’s Envoy, yet recovered of his sickness?”

“No, he is still indisposed, and I am here in his place,” said Stratford, restraining his impatience with an effort.

“Will my lord command his own servants to withdraw a space?” pursued the ambassador, evidently embarrassed, “for I have to mention one who belongs to the great lord’s household.”

Stratford signed to the servants to withdraw a little, but intimated that Dick and Fitz were equally interested with himself in the matter now to be disclosed, while Kustendjian was necessary as interpreter. This having been made clear, they waited with breathless eagerness, for the ambassador seemed very much at a loss for words.

“My lord knows,” he said at last, “that the English doctor lady came this day to visit the household of our lord the King?”

“I know that she received an urgent message in the Queen’s name entreating her to come to the Palace, and that she hastened thither at once,” said Stratford. The official seemed to find a difficulty in proceeding, and his colleague took up the tale.

“However that may be,” he said, “the doctor lady is now in the hands of our lord the King.”

“And how is that, pray?” asked Stratford. “Since when has the King of Ethiopia adopted the plan of getting women into his power by false messages, and then kidnapping them?”

“In dealing with enemies and infidels, our lord the King pays more heed to the end than to the means,” said the Amir.

“So it seems,” said Stratford, drily; “but does he fight with women?”

“Nay,” said the official, plucking up courage to speak again; “he fights with men, and therefore it is that we are here.”

“The King is evidently in need of money, and requires a ransom,” said Stratford, turning to the rest, and speaking with an airy confidence which he was far from feeling. “How much does he want?” he asked of the messengers.

“Our lord desires not money, nor does he war with women,” repeated the Amir. “In exchange for the woman he requires a man.”

A gasp from Fitz, an exclamation from Dick, and a stifled cry from Lady Haigh warned Stratford of the effect which the announcement of the King’s demand had produced on his friends. He himself felt a certain relief—almost akin to the “stern joy” of the warrior—in the conviction that the crisis for which he had been looking had at last arrived, and his voice rang out clearly as he asked, “And who is it that the King requires?”

“My lord must see,” said the old official reluctantly, “that our lord the King desires him who is chief in authority among you to be sent to him, that he may make the treaty with him which the Queen of England desired when she sent her servants hither.”

“But we have no stronger wish than that the King should sign that very treaty,” objected Stratford.

“But my lord’s treaty is not the King’s treaty,” was the unanswerable reply of the ambassador.

“And if the man you desire should go to the Palace, and yet refuse to sign the King’s treaty, what then?” asked Stratford.

“It is not for the health of any man to withstand our lord the King,” was the evasive answer.

“But if—if the man was not given up,” broke in the agitated voice of Fitz from behind, “what would happen to the lady?”

“Oh, the woman would die—in a little while,” was the instant reply of the Amir, delighted to perceive his opportunity. “Not by the hands of the King’s executioners—that would be a man’s death. No; women can deal with women. There are certain in our lord the King’s household who bear no love to the doctor lady. I do not say that they would kill her; but she would not live very long in their hands—a day, perhaps, or it may be two. And it would not be an easy death.”

“For God’s sake, Stratford, put a stop to this!” muttered Dick, hoarsely, his face convulsed with rage. “Tell them I will go.”

“Unless,” pursued the Amir, apparently heedless of the interruption, although his greedy eyes had not missed the slightest change in the expression of any of the faces before him, “the woman should find favour in the eyes of our lord the King. Then she would live for a time. Afterwards it would be much the same; but whether——”

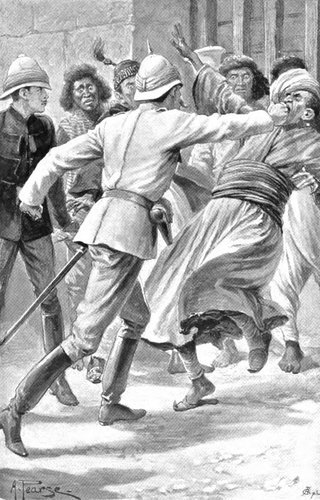

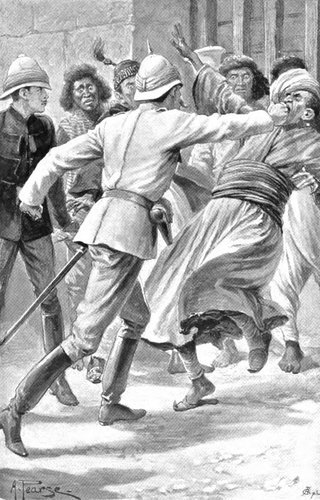

But the alternative which he had been about to state was left unuttered, for Dick sprang forward and dealt him a blow which stretched him on the ground.

Dick sprang forward and dealt him a blow which stretched him on the ground.

“Say that again if you dare!” he growled, standing over him with clenched fists; but the Amir, evidently considering that discretion was the better part of valour, submitted to be helped up and brushed by his attendants, after which he retired to the rear, Dick turning contemptuously on his heel and resuming his post beside Stratford.

“Let not my lord heed the sayings of that man,” entreated the old official, “for he has an evil tongue and loves to stir up strife.”

“Then is what he says not true?” asked Stratford, sternly. And, divided between a desire to maintain the effect produced and the fear of Dick’s fist, the ambassador preferred to take refuge in silence.

“We will consult together upon the matter and let you know our decision presently,” said Stratford, after waiting in vain for an answer. “If you will not enter, the servants shall spread carpets at the gate for you.”

The official expressed his gratitude for the courtesy, and the little party of English retired to the inner court in silence, a silence which was broken by Fitz as soon as they reached the terrace.

“What do you intend to do?” he demanded of Stratford, glaring at him with eyes still full of the horror inspired by what he had just heard.

“Don’t ask me!” said Lady Haigh, taking the question as addressed to herself; and sitting down at the table, she began to sob heavily. “I shall become a gibbering idiot if this sort of thing goes on,” she wailed.

“I don’t know what you wanted to pretend to discuss things for,” said Dick, gruffly. “What’s the good of fooling about with consultations when I told you I was going?”

“Excuse me,” said Stratford, “you are quite mistaken. I am going.”

Lady Haigh ceased her sobs and looked at him in astonishment, while Dick uttered an inarticulate exclamation. Fitz alone retained the power of speech.

“Let me go, Mr Stratford,” he entreated. “Not you; you can’t be spared. My life isn’t of any value; but every one here depends on you in this fix. I would do anything for Miss Keeling, and be proud to do it. You will let me go, won’t you? It doesn’t signify what happens to me.”

“Stuff and nonsense, Anstruther!” said Stratford, good-humouredly. “There is plenty for you to do yet. Don’t you see that when the King has demanded the man in authority, he is scarcely likely to be willing to accept you instead? You are pretty well known in Kubbet-ul-Haj, certainly; but although Fath-ud-Din might be glad to welcome you as a fellow-victim with me, he would hardly regard you with favour as a substitute.”

“What are we to do without you, Mr Stratford?” asked Lady Haigh, piteously. “Sir Dugald left everything in your charge.”

“We must trust that the King will prove to be less bloodthirsty than his ministers,” he answered. “I am not without hopes of making him listen to reason. Still, one must prepare for the worst, of course. North, if you will come with me to the office a minute, I will give you the keys and the seal, and just put you in the way of things a little.”

Dick followed him in silence; but when they had entered the office he shut the door and put his back against it.

“Look here, Stratford,” he said, “you have got to let me go. It is my right, I tell you. I—I love her.”

“Of course you do,” returned Stratford. “I have seen that for some time. That is why I am glad that you will be left to look after her. You will have your work cut out for you if you are to get back to Khemistan after this——”

“Stratford,” said Dick earnestly, “listen to me. This is my business, and it is very unfriendly of you, though you mean well, to try to take it from me. I intend to go.”

“Excuse me,” said Stratford, “but it is my business too. No, I am not hinting at cutting you out, old man—I couldn’t do it if I would. My reason for going is totally unconnected with Miss Keeling, except in so far as her danger has brought things to a climax. I am not going to sign Fath-ud-Din’s treaty; but neither do I intend to be killed if I can help it. I shall take our treaty with me, and if I leave the Palace alive I shall bring that treaty out with me, signed. You will observe that it is not for Miss Keeling that I am risking my life, but simply on a matter of business. I stake my life against the treaty, and if I keep the one I gain the other. Of course, if I fail I lose both. Now do you see it?”

“But I could look after the treaty just the same,” urged Dick.

“No, you couldn’t. You are not a diplomatist, North; you are a soldier, and tact is not exactly your strong point. I know that you could die like a hero; but you don’t shine in statecraft, and I am anxious that no dying shall be necessary, if that is possible. You understand? It is a matter of personal moment to me to get this treaty signed, and I ask you, as a favour, to waive your claim to sacrifice yourself for Miss Keeling.”

“Oh, hang it all!” burst forth Dick. “When you put it in that way, Stratford, what can a man do but make a fool of himself, and let you go? It’s my right, and you take away from me my only chance of showing her that I would die for her, though I can’t manage to please her. But we have rubbed through a good deal together, you and I—oh, there, you can go.”

“Thanks, old man; I thought I knew your sort. That’s settled, then. By the bye, if they should put an end to me it is just possible that they might have some one there capable of imitating my writing. They must have seen my signature on notes and things of that kind. Well, if I sign any treaty you will find the words run into one another, so that the Egerton is joined to the Stratford. That is the test of genuineness, do you see?”

“All right.”

“I leave you in charge of everything here, of course. I am very much afraid that Jahan Beg must have come to grief, so don’t depend upon him any longer. You won’t be able to leave the Mission yourself now, of course; but if you can get one of the servants to venture, send him off to Fort Rahmat-Ullah. The absence of news ought to have put them on the alert, and if they have any sense they will be preparing a rescue expedition already; but you can’t count on that. If you see the faintest chance of getting every one off safely, I charge you most solemnly to seize it at once, without waiting to see what has become of me. Such a message as this means war to the knife, and you must take any opportunity that offers of an escort, for to fight your way through Ethiopia would be an impossibility, with the women and the Chief to guard, and no horses. Perhaps Hicks might join forces with you, if you approached him in a proper spirit, and he would be a real acquisition, for he has a good number of armed servants, and has seen something of Indian fighting on the Plains. If he doesn’t see it, you may have to stand a siege here until relief arrives; but what you are to do about food I don’t know. I can’t attempt to give you directions. All I say is, if the worst comes to the worst, leave me and the treaty alone, and escape as best you can.”

“All right,” said Dick again.

“Here are the keys. Young Anstruther will show you how the papers are arranged. And, by the bye, if I don’t come back, send my things to my sister, Mrs Rowcroft, Branscombe Vicarage, Homeshire, and tell her how it was. She is the only near relation I have, and we haven’t met for nearly twenty years.”

They left the office together, and returned to the terrace.

“Mayn’t I go, Mr Stratford?” cried Fitz, starting up to meet them.

“Certainly not. I told you that before.”

“Mightn’t I come with you, then? We could fight back to back, you know.”

“No, thanks. But I will borrow that large old-fashioned pistol of yours, if you have no objection. You will probably not see it again in any case, so don’t lend it me if it is a favourite.”

Fitz was off immediately, and Stratford turned to Lady Haigh.

“You will think me an unconscionable borrower,” he said, “but there is a miniature revolver of Sir Dugald’s for the loan of which I should be most grateful. It is smaller than any of ours, and easier to hide.”

“I will tell Chanda Lal to look it out at once,” said Lady Haigh, and went to find the bearer.

“Now, Mr Kustendjian, I should like our treaty, please,” said Stratford. “You have nearly finished the second copy of it, I think?”

“Nearly,” said the Armenian, whose English seemed almost to have forsaken him under the influence of horror. “You will have need of me, Mr Stratford?”

“No, indeed. I will take no one into danger with me. Thank you, Anstruther,” as Fitz reappeared with a large brass-mounted pistol. “I will load it simply with powder, I think. It will be less dangerous if it should happen to go off in my coat-pocket. There! How does that look?”

“It sticks out a good deal,” said Fitz, surveying the coat critically. “Any one could see that you had a pistol in that pocket.”

“That is exactly the impression I wish to produce. One thing more you can do for me, Anstruther. Just rummage among the stores, and see whether you can find any description of food that has a good deal of nourishment in very small compass.”

Fitz departed again, and presently Lady Haigh returned with the little revolver, which Stratford loaded carefully and slipped up his left coat-sleeve. Dick and Kustendjian watched him curiously and with respect. It was evident that he had some plan in his head, but neither of them could divine what it was. A minute or two later Fitz came up the steps with a box of meat lozenges in his hand, and presented it to him.

“Will these do, Mr Stratford?” he asked. “They were the smallest things I could find. There were tinned soups, of course, and chocolate; but I thought these would have more nourishment in them.”

“Quite right,” said Stratford; “they are the very thing. Is that the treaty, Mr Kustendjian? I think my preparations are complete, then. You will say good-bye to the Chief for me when he is better, Lady Haigh?”

“Must you go?” whispered Lady Haigh, hoarsely, as she held his hand.

“I must,” he said. “If I should escape, Sir Dugald’s work will have been completed. You will like to remember that.”

“I shall ride to the Palace with you,” said Dick, as they went down the steps.

“It will be just as well, for you will be able to escort Miss Keeling back. It would be a pity for them to keep her in their hands after all.”

Another interruption met them as they emerged from the archway into the outer court. Waiting for them there, with his hand lifted to the salute, was old Ismail Bakhsh the gatekeeper, a former trooper of the Khemistan Horse, the celebrated force to which Dick was attached, and which had been raised in the first instance by Georgia’s father, General Keeling.

“Will my lord tell his servant,” he asked Stratford, “whether it is true what they are saying among the servant-people, that my lord goes to the Palace to give his life for the doctor lady’s?”

“It is true,” answered Stratford.

“Let my lord listen to his servant, for it is not fitting that my lord should accept death for the sake of one who has no claim on him. I served for ten years under Sinjāj Kīlin the general, and I will go in my lord’s place, because I have eaten of Sinjāj Kīlin’s salt, and it is not right that his daughter should come to shame or harm while Ismail Bakhsh lives.”

“Your loyalty to your old general is only what I should have expected from you, Ismail Bakhsh, but the King demands my presence, and not another’s.”

“But would my lord sacrifice himself for a woman—and that woman not even of his house?”

“I would do it for a woman, Ismail Bakhsh, and so would any of us, when we would not do it for a man.”

“It is the way of the English,” said Ismail Bakhsh, thoughtfully, with grieved surprise in his tone. “That my lord should give his life for his lord, the Envoy of the Empress, would be no great matter—but for a woman!”

Stratford laughed.

“Not only I, but all three of us, Ismail Bakhsh, would have given our lives rather than that a hair of the doctor lady’s head should be injured.”

“God forbid!” said Ismail Bakhsh, piously. “Let not my lord speak such words in the hearing of the scum of the earth out yonder, or there will be none, either of English men or women, to see Khemistan again.”

“You observe that, North?” said Stratford. “Any undue display of chivalrous sentiments here is likely to land you deeper in difficulties, so keep them to yourself. Chivalry is at a discount in Kubbet-ul-Haj.”

They mounted their horses, and accompanied the ambassadors back to the Palace, half-a-dozen armed servants following them, in case the King should show a disposition to claim Dick’s life as well as that of Stratford in exchange for Georgia. When the greater part of the journey had been accomplished, and the frowning walls of the Palace courtyard were just in sight, they met the well-known procession of slaves and soldiers guarding the litter, which had so often come to the Mission to fetch the doctor lady.

“Evidently they sent off a swift messenger to tell them that we accepted the terms, and the King is anxious to show that he confides in our good faith,” said Stratford. “Funny mixture, isn’t he? Well, you will turn back here, North, I suppose? There is no particular use in your coming on further.”

“Let me go instead of you,” entreated Dick once more.

“My dear fellow, haven’t I wasted enough breath on you yet? I thought we had threshed all that out long ago, and that you were quite convinced. By the bye, now that we are abreast of the litter, it might be as well for you to make sure that Miss Keeling really is inside. It would be irritating to be fooled now.”

Doggedly Dick pushed his way through the guards, and raised the curtain of the litter, in spite of the loud protests of the slaves. He was fully prepared for a trick; but the eyes which looked up at him through the lattice-work of the burka were unmistakably Georgia’s, and it was undeniably Rahah who flung herself forward to draw the curtain close again, with a shrill rebuke to the slaves for letting some drunken wretch approach the litter.

“Why, Major North, is it you?” asked Georgia, in astonishment. “Is anything the matter?”

“Not much—not exactly,” he stammered. “I—he—we fancied it might be safer if I turned up to escort you home.”

“It was very kind of you,” said Georgia, gratefully. “We had rather a fright at the Palace; but I will tell you about it presently.”

“Yes—very well,” he muttered incoherently, and, drawing the curtain again, turned to Stratford; but his lips refused to perform their office. Stratford held out his hand.

“Good-bye, old man,” he said. “God help you with the job you will have in hand now.”

“God bless you, Stratford!” burst from Dick. “I wish with all my soul that I was in your place at this moment.”

He wrung Stratford’s hand, and turned silently to follow the litter with the servants, while the ambassadors and their prisoner rode on towards the Palace.

“How shall I ever tell her?” was the question which agitated Dick’s mind as they neared the Mission. He knew enough of Georgia to feel sure that, if she been made acquainted with the terms of the King’s ultimatum, she would promptly have gone back to the Palace, and refused to allow any one else to be sacrificed for her, and he quailed under the anticipated necessity of informing her of what had been done. But he was saved this duty, for as he entered the Mission courtyard Mr Hicks came hurrying to meet him.

“Well, Major,” he exclaimed, “the King has been playing it pretty low down on you, I guess. I’m always glad to look on at a fair fight, and it don’t so much matter to me which of the chaps gives the other beans so long as everything is done on the square. But when it comes to getting hold of a woman, and by threatening to torture her, working on a man’s highest feelings to make him give himself up instead, you may bet largely that I don’t stand in with doings of that stamp—no, sir! The moment I heard a rumour of what was going on I made my darkies fly around, and in just half no time I had everything fixed up to come here. You may count on me as a fair shot with a Winchester or a six-shooter if it comes to fighting, and if old Fath-ud-Din and I catch sight of each other, one of us is bound to send in his checks, or I’ll never look a woman in the face again. Your nation and mine are not always sweet to each other, sir; but if there’s any question of a woman in danger, you may count upon Jonathan to the last drop of his blood.”

“Much obliged,” muttered Dick; but under his breath he grumbled, “I wish that voice of yours wasn’t quite so loud.”

Georgia was being helped out of the litter at the moment, and as she reached the ground she cast a quick, apprehensive glance about her. Her hand was on Dick’s arm; Fitz was coming through the archway, and Kustendjian was visible on the verandah of the Durbar-hall. Ismail Bakhsh and his subordinates stood by the gate, looking at her with disapproving eyes, silent and grim, and her mind filled up in a moment the gaps in Mr Hicks’ speech. A sob broke from her as she stood gazing from one to the other; then her hand dropped from Dick’s arm, and, gathering her burka around her, she passed on into the inner court. Dick followed, with a vague notion of saying something to comfort her; but at the foot of the steps she turned and faced him.

“You let Mr Stratford go to the Palace in exchange for me—you let him?” she asked sharply, and waited for his answer with breathless anxiety.

“I tried to prevent him—he would go,” stammered Dick.

“You let him sacrifice himself to save me? If anything happens to him I will never, never speak to you again as long as I live!” and she turned her back on him and fled up the steps. He stood looking after her, stupefied.

“She cares for him, and I never guessed it,” he muttered to himself. “I might have saved him for her, and I have let him go and get himself killed by those fiends yonder!”