CHAPTER XV.

ONE CROWDED HOUR.

Throughout that long day, Dick worked with feverish activity at anything that offered itself as an outlet for his energies, without cherishing the least hope that his friend’s sanguine anticipations of a possible change for the better in the attitude of the King and Fath-ud-Din would be realised. It was his opinion that the worst had come to the worst, and that as soon as Stratford had met his death at the Palace, a general attack upon the Mission premises would take place, with the view of making it appear that all the members of the expedition had been murdered in a popular tumult. With this cheering prospect in view, he prepared the building for defence, instructed the servants afresh as to their respective duties in case of an assault, and placed the stands of arms where their contents could most readily be seized on an emergency. Fearing that an attempt might be made to starve the Mission into a surrender, he bought up all the provisions which the country-people brought in, and even induced them by liberal payments to sell him a supply of corn which they had intended to dispose of in the city market.

Having thus made preparations for resisting a siege as well as a sudden assault, he was forced by his very need of occupation to take somewhat wider views, and to consider the improbable possibility of evacuating the place safely. Accordingly he summoned Ismail Bakhsh, and, setting before him the facts of the case, asked whether he would undertake the dangerous task of conveying a message to Fort Rahmat-Ullah. He did not attempt to minimise the risks to be incurred; but the old soldier was faithful to his salt, and consented to attempt the journey in disguise. His trained eye had enabled him to observe the features of the route traversed on the journey to more purpose than his younger companions had done, and he was persuaded that if he were once safely outside the walls he could make his way to the frontier without much difficulty—provided, of course, that his absence was not discovered, and a hue and cry set on foot. A certain addition to his pension in case of his success, and compensation to his family if he was killed, were agreed upon, and Ismail Bakhsh retired, leaving Dick to face the inaction which he had been combating all day.

He could not think of anything else to do, beyond going the round of the walls at absurdly short intervals and seeing that the servants were keeping a good look-out; and the more personal troubles, which he had been trying to keep at bay, crowded upon him and would not be put aside. The day had cost him both his friend and the woman whom he loved—and who loved that friend. The miserable irony of the situation seemed to mock him afresh whenever he tried to face it. Georgia loved Stratford, and Stratford had gone to his death to save her—yet not because he loved her, but because he saw in the action a chance of doing a good stroke of business—while he, who would willingly have died for Georgia’s sake, remained alive, to meet the grief and anger which she would naturally feel at his having allowed his friend to sacrifice himself for her.

Wretched as the outlook appeared to Dick, however, it is a question whether it was not even more dreary for Georgia, since his conscience was clear, and hers was not. She could not rid herself of the conviction that if she had done as Lady Haigh advised, and declined to go to the Palace without first consulting Stratford, he might even now be free and in comparative safety, while if he had given her leave to go, she would not have had herself to reproach for his untoward fate. It was so unlike her usual practice to act on the impulse of a moment of irritation, as she had done in this case, that she asked herself what could have made her refuse so decidedly even to communicate to the gentlemen her intention of visiting her patient. She had not far to seek for an answer. It was Dick whose opposition she had feared. She had been so obstinately determined not to appear in the slightest degree willing to ask either his opinion or his advice, after the words he had uttered in the heat of their discussion, that she had sacrificed his friend and hers to her wounded pride.

Nor was the realisation of this fact her sole punishment. Whatever Dick might think, she had no illusions as to the frame of mind in which Stratford had gone to the Palace. His story she had early heard from Lady Haigh, with the addition of the significant remark that he was never likely to marry now, and it had given her a distinct thrill of pleasure when she found that this faithful lover was willing to be her friend on the footing she liked best. The greater number of her medical confrères in London, and of the many men whose friendship she had gained and kept since her hospital days, had been content to accept her terms and to meet her on the equal ground of comradeship. Some there had been, as Mabel had told Dick, who were anxious to go further, and had been courteously though firmly repulsed; but Stratford was not one of these. He had made a friend of her as if she had been a man, she thought, and he had sacrificed himself for her in exactly the spirit he would have exhibited if Lady Haigh had been in danger, and not Miss Keeling. She knew well enough that there was no personal feeling whatever in his case, but it was different with Dick. Why had he allowed Stratford to go instead of going himself? He did care for her—at least, she had begun to think so until his plain speaking of a week ago had created the breach between them. But now she was on the horns of a dilemma. Either he could not care for her, since he had left it to another man to give his life to save hers, or else, if he did care for her, he was a coward who was willing to shelter himself behind the other man’s self-sacrifice. But Dick’s past record was sufficient to put the latter supposition beyond the bounds of possibility, and Georgia was thrown back upon the former. He could not care for her, and she cared for him. To the woman whose heart had never been touched before, the thought was almost unendurable in the shame it brought with it.

And she had sent Stratford to his death! What would there have been in the slight humiliation—more fancied than real, after all—involved in asking his leave as head of the party before quitting the Mission, compared with the overwhelming remorse and misery which now oppressed her? She recalled the threats launched against herself by Antar Khan’s mother, and sobbed and shuddered at the thought that the tortures of which the mere mention had been considered sufficient to terrify herself were now being inflicted on another, and by her fault. Lady Haigh, who came wandering in and out of her room like a restless ghost, could offer her no comfort, since the best they could hope for was that Stratford was dead already, cut down by the guard in some conflict provoked by himself, and that he had thus died without either torture or indignity. The two women could not endure to talk, could not even pray; they could only weep in concert and exchange half-uttered surmisings which were worse than certainties.

The day wore away, and Mr Hicks, who had spent the greater part of it busily and happily in passing all the rifles in review, cleaning them and adjusting the mechanism, came to Dick, as he sat brooding gloomily over the state of affairs in the office, and represented mildly but firmly that the whole party would be the better for some dinner. He had put up with the absence of tiffin under the painful circumstances of his visit, he said; but he could not see that because one poor fellow had got wiped out all the rest must necessarily starve. Thus reminded that he had taken no food since breakfast-time, Dick awoke to a perception of the duties of hospitality, and apologising to Mr Hicks for the inconvenience and discomfort to which he had been subjected, ordered the meal to be served at the usual hour. It was a very small and lugubrious company that met in the dining-room. Dick had sent a message to the ladies, asking whether they would appear at table, but no answer was returned; and Mr Hicks was the only person who possessed an appetite. He did his best to worry his hosts into eating something, but he was not very successful; and at last Fitz left the table suddenly, muttering something about the flag, which he feared had not, in the general confusion, been hauled down as usual at sunset. As the noise of his hurrying footsteps on the stones of the terrace died away, another sound became audible—the blare and din of native music, the shrill cries of triumph of women, and the approaching tread of a multitude.

“It’s coming at last!” cried Dick, springing up from his seat and buckling on his sword. “You know your post, Hicks?”

“Wait a minute, Major,” said Mr Hicks. “Doesn’t it strike you that this is rather a new way of conducting an attack?”

“Why, what else could it be?” asked Dick.

The American turned aside, and would not meet his eye as he answered—

“Well, if they have put an end to the poor fellow, I would bet my last red cent that they would carry his remains about in procession to show the people—to show us, too, for the matter of that—and it won’t be a pretty sight for the ladies to see, any way.”

“Good gracious, no!” cried Dick. “Say nothing to them at present, Hicks. We will just order the servants to their posts without troubling the ladies, and then watch from the gate and see what happens.”

They went down into the outer courtyard, sent the servants to their appointed places without any noise or confusion, and took their stand at the window over the gateway, where they were joined by Fitz and Kustendjian. They stood there, waiting breathlessly, for some minutes, each man’s hand on his weapon, while behind them the fierce eyes and gleaming blades of Ismail Bakhsh and his subordinates reflected the glare of the torches which were now beginning to appear at the end of the winding street. Nearer and nearer came the crowd, apparently all mad with joy, leaping, dancing, tearing off clothes and flinging them on the ground, waving torches, shouting, singing, and yelling. Some looked up at the window as they passed it, and it seemed to the little band of white men standing there that their gestures became intolerably derisive, and that their faces took on a fiendish grin as they massed themselves in the street beyond the Mission and waited—in so far as those still pressing upon them from behind would allow them to wait. Dick felt his heart thumping against his ribs; he was aware that Kustendjian had sat down in a corner and hidden his face from the horror he expected to see, that Fitz was leaning against the wall with white lips and staring eyes, and that Mr Hicks was uttering spasmodic exhortations at momentary intervals—“Steady, boys! Keep up; don’t let ’em see you wilt. Never give in!”—such as bespoke rather, perhaps, the turmoil of his own mind than his estimate of the state of feeling of his companions.

“Soldiers!” murmured some one, and a squadron of cavalry defiled slowly past, saluting as they came level with the window—a piece of mockery for which Dick cursed them in his heart. Then more torches, more musical instruments, more excited people, banners, dancing-girls, gliding and posturing to the sounds of the music, with their long coloured scarfs twirled daintily on the tips of their outspread fingers; and then two men riding alone, wearing robes of honour. As they reached the gate they paused and waited; then one of them looked up, and in tones of extreme calmness addressed the group at the window.

“You don’t mean to keep me here all night, North, do you? Mr Anstruther, I give you my word of honour that I am not a ghost yet.”

How they got down the stairs and opened the gate none of them ever knew, but in another minute Stratford was among them, unhurt, and indulging in a little chaff by way of maintaining his own composure.

“I wonder you didn’t shoot me when I looked up just now, North. If ever I saw murder in a man’s eye, I saw it in yours then. Mr Hicks, you have as keen a scent for a battle as any vulture. The way you turn up when you think we are likely to be in trouble is positively pathetic. I have some further use for my arm, Anstruther, if you have finished wringing my hand off. Peace be with you, Ismail Bakhsh! I fear you are disappointed that there is to be no fighting to-night?”

“My lord is pleased to jest,” said Ismail Bakhsh, reprovingly, as he directed the closing of the gate. The processionists outside had turned back, and were marching homewards amid a fresh outburst of minstrelsy, with the man who had accompanied Stratford at their head. No one thought of asking who he was, nor, indeed, of paying the slightest attention to affairs outside, as Stratford was assisted, quite unnecessarily, to dismount, and escorted through the archway into the inner court. But he was not to arrive altogether unheralded. Brought to his senses by Stratford’s commonplace greeting, Fitz had dashed across the court and up to the terrace, the only man who remembered in the excitement of the moment that the joyful news ought not to be allowed to burst suddenly upon the ladies. The fresh hope in his voice—a hope to which they had been strangers for what seemed interminable hours—roused them from their lethargy of grief, and they came out into the verandah with tear-stained faces and ruffled hair, both looking as though they had cried until they could cry no more.

“Good news, Lady Haigh!” panted Fitz. “Miss Keeling, they haven’t murdered him after all. He is not a bit hurt. He will be here in a minute. He’s here now!”

This method of breaking the news, though strictly gradual, could scarcely be called gentle, and Lady Haigh and Georgia stood staring at Fitz without understanding him in the least. Seeing this, he tried a new plan, the first that recommended itself to his excited mind.

“Aren’t you going to put on your best things to greet the hero in, Miss Keeling? He’s dressed up to the eyes himself. You never saw such a get-up—most awfully swagger. You will never be able to keep him in countenance.”

“Oh, you absurd boy!” cried Georgia, and she sat down at the top of the steps and laughed wildly.

“Fetch me a jug of water, Mr Anstruther,” said Lady Haigh, sternly. “You are getting into a way of going into hysterics, Georgia, and I mean to break you of it. This is the second time I have caught you at it since we came to Kubbet-ul-Haj, and it’s not professional.”

“Professional?” echoed Georgia, beginning to laugh again; “it is the circumstances that are unprofessional, not I. Besides, I am not in the least hysterical. Thank you—a little water—please—Mr Anstruther.”

The water, applied internally, and not as Lady Haigh had intended, proved efficacious, and when Stratford and the rest approached the terrace, Georgia had recovered her composure. She met Stratford as he mounted the steps, and held out her hand to him. Dick, seeing the action, turned his eyes away, and listened in sick terror for what would follow. After all, Stratford had the right to win her now if he chose to exercise it. But if he did not choose? Would he humiliate Georgia by repulsing her before them all? But Dick need not have been afraid. Even his jealous ear could detect in her tones merely the amount of feeling natural and unavoidable under the circumstances, although her eyes were swimming with tears as she said—

“I can never thank you enough for what you have done to-day, Mr Stratford. If I don’t seem as grateful as I ought to be, you must only think that I can’t blame myself properly for my foolishness and obstinacy in going to the Palace without leave as I did, since it gave you the opportunity of doing such a deed of heroism.”

Every word went to Dick’s heart, as, alas! it was meant to do. He waited anxiously to hear Stratford say that he had gone to the Palace merely as a speculation of his own, and that Miss Keeling had had very little to do with the matter, but the words did not come. Stratford was not the man to hurt a woman’s feelings gratuitously by an uncalled-for rebuff, however true its nature, and he answered at once—

“You are too kind, Miss Keeling. I assure you that there was an eager competition for the honour of helping you out of your little predicament. Anstruther was bent on going; and as for North, I had to keep him back almost by main force. He was only restrained at last by a combination of definite orders, personal entreaties, and solemn assurances that my going was for the greater good of the Mission.”

Georgia’s eyes were raised to Dick’s for a moment, and the expression in them said, “You might have told me!” But his eyes met hers with a steady hostility, which revived all the bitter feelings which had tormented her during the day.

“I am afraid I did you an injustice, then, Major North,” she remarked, sweetly. “You must take into account the circumstances of the moment, and kindly forgive my hasty words. I am only a woman, you know.”

Dick bit his lip, and tried hard to think of something cutting to say. Was it fair that this woman, who had treated him so unfairly—no, not unfairly, cruelly—well, not exactly cruelly, slightingly—no, not that, carelessly, perhaps—should also have the power of making him writhe in this way? And he loved her! He had even told Stratford so! How Stratford must be laughing at him in his sleeve at this moment! All this passed through his mind as he stood staring dumbly at Georgia until Lady Haigh, who had caught the look in his eyes, pushed her gently aside, and addressed herself to the hero of the occasion.

“And you escaped without signing their treaty?” she asked.

“I did not sign it, certainly,” he replied.

“And what about our treaty?” asked Fitz, eagerly.

“There is our treaty—signed,” returned Stratford, with a queer gleam in his eyes as he laid the parchment on the table. “When the Chief gets better he will find that his work was not all in vain, Lady Haigh.”

Lady Haigh blushed afterwards to remember that she was ready to kiss Stratford there and then in the first flush of her delight at the news; but she restrained herself sufficiently to do no more than wring his hand without a word. The rest were examining the treaty, which bore Stratford’s signature and another, as well as the King’s seal and that of the Grand Vizier.

“But that is not Fath-ud-Din’s signature,” said Kustendjian, who was looking at the parchment from the other side of the table.

“No,” said Stratford, drily; “it is Jahan Beg’s.”

“Jahan Beg’s?” was echoed, in tones of astonishment.

“Yes; he has succeeded Fath-ud-Din as Grand Vizier. You have a good deal to hear; but I should like some dinner first, if there is any going.”

“Have you had nothing but meat lozenges all day, Mr Stratford?” asked Fitz, laughing; and every one adjourned to the dining-room, where the dishes, which had been left untasted half an hour before, were still on the table. Everything was cold, of course, and the servants were in despair; but the makeshift meal was the most cheerful that had taken place during the whole sojourn of the Mission in Kubbet-ul-Haj, and when it was over, the party returned to the terrace, and demanded clamorously of Stratford that he should tell his story.

“It is rather long, and I am afraid you will find it a little tedious,” he said, throwing away his cigarette; “but I can assure you that the experience was much more tedious to go through than to talk about. Well, no attempt was made to molest me when I got to the Palace, and I started off as usual in the direction of the hall of audience. Generally, as you know, when we have gone to the Palace, there have been a lot of chamberlains and fellows to clear a path for us and bring us to the King, but to-day I had to elbow my way through the crowd that was hanging about. It was a sign that times were changed; but that wasn’t all, for, before I had got half-way through the mob, I felt a pull at my coat-tail, and when I could put my hand there, I found that I had been eased of my pistol. However, as I had put the pistol into that pocket for the express purpose of having it seen and stolen, I didn’t mind much. When I got to the door of the audience-chamber, the guard made a fuss about letting me in; but I said that the King had sent for me, and I meant to see him. When they saw that I would stand no nonsense, they let me pass, and I found the King and Fath-ud-Din, as I had hoped, in the room in which they had tried to bribe the Chief to sign their treaty. It is quite small, you remember, and the walls are solid, without any of the lattice-work panels you see in the big hall. The windows are high up, and all the open carving is of stone, and not of wood. It was another score for me that the King thought fit to treat me as a criminal, and didn’t invite me to come close to him, so I chose my position, and camped in the corner in a line with the door, and opposite to the King’s divan. Of course this was nominally in order that what we said should not be overheard outside. They brought in coffee; but I refused to taste it, for I didn’t see any advantage in being poisoned at the very outset, and there was no object in keeping on the mask of friendliness any longer.”

“Wait a minute,” said Dick. “How did you manage everything without an interpreter?”

“I got out my best Ethiopian for the occasion, and when that failed we had recourse to Arabic,” returned Stratford. “The King and Fath-ud-Din can both talk it pretty well when they like, as you know. Well, when war had once been declared by my refusing the coffee, we sat for hours arguing. It was intimated to me pretty clearly at the beginning that if I didn’t sign their treaty, I should not leave the Palace alive; but when they saw that that didn’t seem to affect me to any appreciable extent, they began to add inducements on the other side. They offered me money and precious stones—quite a comfortable little fortune, I should think—rising by degrees until either their tempers or their purses gave way. Then, evidently thinking that my obstinacy arose from a fear that the rest of you would split upon me, they offered to put every one else belonging to the Mission out of the way, and to send me back to Khemistan as a conquering hero, returning with the best treaty I could manage to obtain. When they found that wouldn’t do, they offered me Jahan Beg’s office and property if I would only sign. I was to disappear from the ken of mortals outside Ethiopia, of course, and they would represent that the Mission had all been carried off by a pestilence, leaving only the treaty behind them. Their ideas as to English credulity are distinctly Arcadian. Well, all this time the servants kept bringing in sweetmeats and sherbet and fruit; but I would not touch anything, though I was abominably thirsty, for I remembered what Miss Keeling had said about some poison that destroyed the will, and I didn’t want to be hocussed into signing. Then they started on a fresh tack, and had in a crowd of dancing-girls——”

“The temptation of St Egerton!” cried Fitz, hugely delighted. “Were they very fascinating, Mr Stratford?”

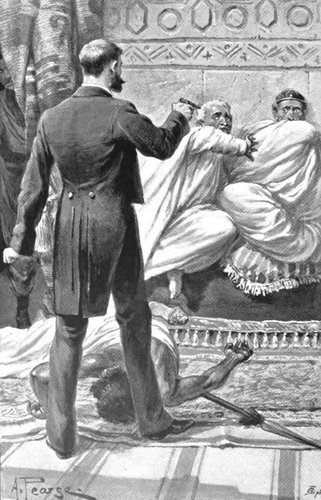

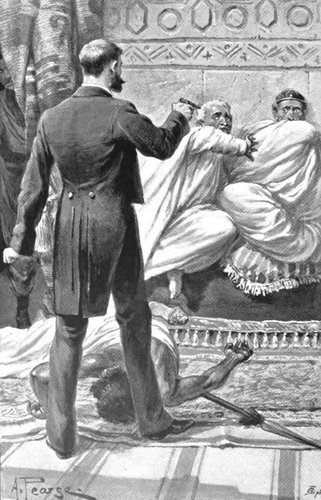

“You might possibly have found them so,” returned Stratford, coolly; “but my tastes don’t happen to lie in that direction. I endured their performances for some time, and then they began to get tiresome. It was rather hard on the poor things, I know, for they were doing their level best; but I yawned aggressively, and suggested that we should go back to business. They bundled the girls out, and I found that the King and Fath-ud-Din had about reached the end of their patience. They took to threats now, and discoursed movingly for some time on the subject of tortures, with a strictly personal application. Fath-ud-Din did most of the talking; but when the King thought that his language was lacking in vigour, he added a few stronger touches to the picture. At last I remarked that this was all very interesting, but it wasn’t business, and that set them off. The King stamped on the floor, and immediately the curtain over the door was pulled aside, and a gang of the most villainous-looking negroes I ever saw filed in. ‘Seize that white devil,’ said Fath-ud-Din, ‘and let our lord the King behold your skill.’ That was all very well, but there were two sides to the question. ‘Stop,’ I said to the foremost black fellow as he turned towards me—‘cross that line in the floor at your peril!’ He laughed. I believe they thought I meant to take it fighting; but that was not my game at all. In a rough-and-tumble fight with those niggers I should have gone under in no time, and I didn’t exactly see being pulled to pieces with red-hot pincers to make a holiday for the King and Fath-ud-Din. I had slipped the little revolver down my sleeve and into my right hand, and I had some extra cartridges in my left, and as the man set his foot on the line I had pointed at, I shot him straight off. It was rather a strong thing to do; but it was my only chance. The other black fellows drew back as the first man fell forward on his face, his arms almost touching the King, and Fath-ud-Din opened his mouth to yell out to the guard; but I spoke first, slipping in another cartridge into the chamber I had fired. ‘I have six shots here without reloading,’ I said. ‘The next two are for the King and the Grand Vizier, as soon as either of them moves or speaks; the rest are for the first four men that cross this line.’”

“I have six shots here without reloading,” I said.

“Sir,” said Mr Hicks, approvingly, “there was a dreadful smart newspaper man lost when you were raised for a diplomatist.”

Stratford smiled in acknowledgment of the compliment, which was delivered with even more than the amount of drawl which Mr Hicks chose usually to affect.

“Well, there was a moment’s pause,” he went on, “which I utilised in surveying the position. I had the King within easy range, with Fath-ud-Din standing beside him, and to reach the door they would have to pass me. I was in the corner, so that even if the guard came in they could only reach me in front. Of course they could have floored me easily if the black fellows had come at me in a body; but it would have been the last fight for two or three of them, and they knew it and kept quiet. The only danger was that they might fire at me from the door or from the outside of one of the windows when the guard found out what had happened, and I saw that if I was to get off we must come to terms before any one in the great hall suspected anything. What they made of the sound of my revolver-shot I don’t know, but it doesn’t seem to have struck them as anything suspicious; perhaps they thought that the King was amusing himself with practising shooting at me. No one appeared, at any rate, and I spoke to the King again. ‘Before we do anything further,’ I said, ‘I should be glad to know where Jahan Beg is.’ Fath-ud-Din instantly replied with great gusto that he was expiating his crimes in the King’s deepest dungeon, which he would never leave alive. I remarked that it was just possible some one in that room might die sooner than Jahan Beg did, which made him calm down a little, and then I asked the King what crime Jahan Beg had committed. He did not fly out as Fath-ud-Din had done, but told me quite quietly that it was unwise in me to inquire after the traitor who had done his best to deliver Ethiopia into our hands. I asked what he meant (of course I kept my eyes about me and the revolver ready all this time), and he told me a very circumstantial story, the recital of which was intended to cover me with confusion. It seemed that Fath-ud-Din, as soon as the Chief had definitely refused to gratify him by extraditing Jahan Beg on account of some imaginary crime, told the King that he had strong reason to suspect his rival of intriguing with us. He was sure he was an Englishman, and he believed that he was plotting with the English to dethrone the King and put Rustam Khan in his place. The King was loath to suspect Jahan Beg, and particularly anxious not to have to find a substitute for him in the frontier work which he alone could do; but the Vizier was so positive that he consented to set spies to watch him. Of course they saw him come to us at night and found out that he was supplying us with corn, so he was promptly arrested and thrown into prison, and the charge considered proved.”

“You must have been pretty well stumped at that,” said Dick. “It was a mad thing for Jahan Beg to continue to come here as he did when he knew that Fath-ud-Din suspected him.”

“Yes,” said Stratford; “my only chance was a sudden attack by means of a tu quoque. ‘Yes,’ I said, ‘Jahan Beg is an Englishman, and he came to the Mission to visit the Envoy, who was an old friend of his. But he did not come with any view of interfering in public matters. He has never sought to engage our help in placing Rustam Khan upon the throne, nor in making any change in the government of Ethiopia, and we should not have granted it if he had. In fact, his coming was so entirely unofficial that we did not even take advantage of his visits to the Mission to seek his assistance in the negotiations which the Grand Vizier was carrying on with us at the time. When Fath-ud-Din used to visit the Envoy by night, and even when he came to try and arrange the secret agreement about Antar Khan’s succession to the throne, we did not invite Jahan Beg to be present, because we knew that the matter was not intended to be made public, and we feared to produce the impression that our friend was endeavouring to thrust himself uninvited into the King’s counsels.’ I saw in a moment that the shot had told. The King turned and glared at Fath-ud-Din, and then again at me. ‘What!’ he cried. ‘Fath-ud-Din desired to set my son Antar Khan upon my throne?’ ‘He came merely to attempt to secure the support of her Majesty’s Government for the Prince in case that should happen which England and Ethiopia would alike deplore,’ I said, as soothingly as I could; but the King was not mollified. ‘He sought to obtain assurance of English support in case of my death?’ he cried. ‘Yes,’ said I; ‘and when we refused to enter into the arrangement, saying that the matter was one for the King and his Amirs to settle among themselves, he threatened that he would seek the assistance we denied him from the Envoy of Scythia, who would not refuse it. Is it possible that he was not acting on behalf of your Majesty, after all?’ ‘Fath-ud-Din,’ said the King, ‘are the words of the Englishman true?’ ‘O my lord,’ said the old villain, flopping down on his face before the divan in an awful fright, ‘the Englishman’s tongue is forked. He seeks to save himself from the fate he merits by casting dirt upon the name of the meanest of my lord’s servants; but he shall yet eat his words.’ ‘The matter is in the hands of the King to prove,’ I said; ‘let him send and fetch Jahan Beg straight here