CHAPTER XVIII.

RETREAT CUT OFF.

Two or three days after Georgia’s visit to the Lady Nafiza, messengers from Rustam Khan reached the city, announcing that his expedition had been entirely successful, and that he was bringing back with him the servants and baggage-animals of which the travellers had been deprived. This was good news, and once more preparations for departure occupied all those in the Mission. But before the triumphant general had returned to the capital, and while Stratford and Dick were still superintending the packing of cases which it was necessary to pile up in the front courtyard until the means of transport arrived, Mr Hicks looked in to bid farewell to his English friends. His mules and camels had not been impounded, and he was therefore able to start on the morrow. Stratford was somewhat surprised that he did not defer his journey for a few days, and ask permission to attach himself to the Mission caravan; but Mr Hicks explained that he preferred to travel in comfort, and not to find all the inns occupied, and the markets cleared at every stopping-place along the route, by the train of the British Envoy. He did not add that he was calculating on bringing to Khemistan the first news respecting the Mission that had arrived since the interruption of communications, or that he anticipated driving an excellent bargain for himself and the paper he represented by the sale of the unique information he possessed; but he had a proposal to make to Stratford which rather surprised him.

“I guess you calculate on being able to make tracks in safety now, Mr Stratford, but I don’t know that I am quite with you there. I allow that you have had almighty luck, and that you have plucked the flower success from the nettle danger in a style I admire. A month ago I would have bet my bottom dollar that you would never leave Kubbet-ul-Haj without conducting another high-class funeral in that burial-lot of yours, and reading the Episcopal service over the old man, any way. But there’s real grit in you, sir, and I don’t mind making you a present of that acknowledgment before the general public throughout the universe gets hold of it in the columns of the ‘Crier.’ Still, I don’t consider that the prospect before you is exactly a shining one. It would have taxed Moses himself to fix your return trip satisfactorily. Once you get outside these walls, you will have to defend the whole outfit by the light of nature, for you have never been on the Plains, any of you.”

“Still,” said Stratford, with some coldness, “Major North is an experienced soldier, and Mr Anstruther——”

“Is an amusing young cuss. I beg your pardon for taking the words out of your mouth, Mr Stratford, but I can reckon up those two boys as well as you can. Major North is a pragmatic piece of wood, that would stand to be cut to pieces rather than budge an inch——”

“Excuse me if I interrupt you in my turn, Mr Hicks. Major North is my friend, and if I hear any more disparaging remarks about him I shall feel bound to turn you over to Miss Keeling. She would know how to resent them properly.”

“You are right, sir, she would. And that brings me to my point. Thinking over your position here, and the probability of the King’s turning nasty (for I guess there are few crowned heads that would care to send away in peace a man that had driven them to change their minds by the gentle compulsion of a cocked six-shooter), I concluded this morning to offer to escort the ladies to the frontier. I travel lightly, and stand to cover the ground much faster than your big camel-train, and there is no animosity against me. If they are once safe in Khemistan you can come on behind with the old man and the baggage, and feel easy in your minds. Now don’t get riled and say things you’ll be sorry for afterwards, Mr Stratford. I am not impugning your prudence, nor yet your powers of fighting. We have to face facts. It gives any one who is inclined to be troublesome a colossal pull over you that you have the ladies to look after, and if they were put in safety it would diminish at once your anxiety and your liability to attack.”

“What do you think North will say to this?”

“Who bosses this show, Mr Stratford? If Major North displays an unbecoming spirit, put him under arrest. You are too sweetly reasonable with the boys ever to do much good with ’em.”

“But you don’t imagine that the ladies would go?”

“That is for them to decide. Give them their choice, any way. I guess if they won’t go, they won’t; but let ’em have the chance.”

Stimulated by the equitable spirit displayed by Mr Hicks, Stratford broached the subject to the ladies during tiffin, and was not surprised to find that they received it with most ungrateful scorn. Lady Haigh simply expressed her determination to remain with Sir Dugald at all hazards (a resolution which Mr Hicks, in a talk with Stratford afterwards, unfeelingly likened to that of Mrs Micawber), and Georgia refused with much emphasis to desert her patient. To the no small amusement of Mr Hicks, he discovered, from a piece of by-play which attracted his notice, that Dick, once fully assured that she would not go, was disposed to suggest, with an air of superior wisdom, that it might be wiser if she did.

“You know, Georgie,” pathetically, “that I should feel ever so much happier if I knew you were in safety.”

“My dear Dick,” solemnly, “nothing would induce me to go, under any circumstances.”

“Not if I told you that it was my wish?” tenderly.

“If you are wise, Dick, you won’t attempt to bring into play in this case any authority you may imagine that you possess,” warningly; “nor in any other case in creation, either,” interjected Mr Hicks, sotto voce.

Thus it happened that Mr Hicks started on his journey alone, and that the ladies formed part of the procession which filed out of the Khemistan gate of Kubbet-ul-Haj about a week later. A comfortable litter, carried by two mules, had been procured for Sir Dugald, but only the household servants were aware of the nature of his illness, or knew how completely it incapacitated him for ordinary life, and Ismail Bakhsh and his subordinates formed a bodyguard round the litter. It was their business to keep any idea of the truth from reaching the camel-men and mule-drivers, who were regarded with a certain amount of suspicion on account of their long separation from the rest of the party. One or two of the servants who had originally accompanied the Mission from Khemistan had died during the interval; several, according to the testimony of their jailers, had succeeded in making their escape, and the places of these had been filled up by Ethiopians, so that it was just as well to allow them to imagine that although the terrible Envoy was so ill as to be unable to mount his horse, and must be carried in a litter like a woman, yet he still directed the course of affairs, and gave orders which Stratford merely carried into effect. Jahan Beg accompanied the travellers for the first few miles of their journey, and parted from them on the crest of a rise from which the first view of Kubbet-ul-Haj could be obtained by those approaching the city.

“I wish I could have gone with you as far as the frontier,” he had said to Stratford, “but I daren’t leave the city just now. I believe I am on the brink of discovering a very neat plot between the Scythian agent, who ought to be across the border by this time, but is supposed to be detained by illness at a village only a day’s journey off, and Fath-ud-Din’s adherents. I think I have tracked nearly all the participators, and when I am ready I shall give them a surprise. The plan is, of course, to get rid of me and destroy the English treaty. By the way, I hope you are careful of your copy. Accidents will happen, and if that should be stolen or destroyed, it would be a big score for them. If you should chance to be detained anywhere by sickness or a difficulty in obtaining provisions, you will do well to send on some one you can trust, with ten or twelve well-armed men, to make a dash for Rahmat-Ullah, and put the treaty in safety. Our copy, of course, is safe as long as I am, but no one can tell how long that will be. All Fath-ud-Din’s fortresses are refusing to yield except to force, which is another thing that makes me think they anticipate a speedy return to the old state of affairs, and I shall be obliged to send Rustam Khan with the army to reduce each one in turn. You will have to pass not far from two of them; but if your guides are trustworthy and know their business, they ought to take you by without even coming in sight of them. One of the forts ought to be mine, which makes its resistance all the more irritating. Fath-ud-Din did me out of it with the help of some devilry practised by the old witch whom he keeps to get rid of his friends for him. Perhaps I shall get it back now. Well, good-bye; keep an eye on your guides and a tight hand over your men and the escort, and when you get the welcome you deserve at home, don’t quite forget the man who disappeared.”

He shook hands with the rest of the party, and turned away abruptly to begin his ride back to the city. As Georgia looked after him, something of pity rose in her heart. After all, the only tragedies in Kubbet-ul-Haj were not those of the older women with their woful past, and Nur Jahan with her comfortless future. There was tragedy also in the story of the man who for life’s sake had given up all that ennobled life, and who had gained so much that he found was valueless, and lost so much that he now knew was invaluable. Alone in the great cruel faithless city, his only memorial of the visit of his friends the rough tablet which marked Dr Headlam’s grave, his only trustworthy companion the wife whose love he had slighted, his daily occupation the search after any means by which he might succeed in maintaining his position on the slippery height he had reached—there was little reason to envy Jahan Beg.

The march which now began was by no means devoid of incident, but during the first few days, while the caravan was still in touch with the city, everything went well. It was when the dried-up pasture-lands and the scattered villages had all been left behind, and only the sands of the desert were to be seen on every side, that the troubles of the Mission began again. Their commencement was marked by a small but alarming mutiny among the escort of irregular cavalry, who accused their captain of appropriating to his own use half of the bakhshish promised them as a reward for their services, which had been handed over to him at the beginning of the journey for distribution among his troopers. It had been arranged that each man should receive the remainder of his share when Fort Rahmat-Ullah was reached, but they demanded that it should be paid down immediately, if they were to escort the Mission any further. To yield to this attempt at extortion was manifestly impossible, since there was nothing to prevent the men’s demanding extra gifts until the travellers were bereft even of the necessaries of life; but nothing less than a complete surrender to their wishes would satisfy the mutineers. The English met informally in Stratford’s tent to consider the situation (it was early in the morning, and the preparations for the day’s march were interrupted by this untoward event), and admitted to their councils the Ethiopian captain, who had brought the news that the men refused to move until their demands were conceded.

“If we don’t stop this at once,” said Dick, “things will get serious. Stratford, I should be glad if you would leave the matter to me to deal with.”

“By all means,” said Stratford; “but what do you intend to do?”

“Make an example of the chaps that are stirring them up,” said Dick, grimly, taking out his revolver and making sure that all the chambers were loaded.

“But we shall have to get hold of them first,” objected Stratford.

“Exactly. That’s what I’m going to do.”

“Stuff! You are not going down among them alone, I can tell you.”

“We can’t waste more than one man over this business. Look there,” and he threw a significant glance at the trembling Ethiopian captain, “you can see what he thinks of it. I’ll take Ismail Bakhsh with me. Lend him your revolver.”

“Oh, Dick, what are you going to do?” asked Georgia in astonishment, as she met Dick outside the tent, revolver in hand, with Ismail Bakhsh stalking after him with inimitable dignity and determination, his right hand thrust into his girdle.

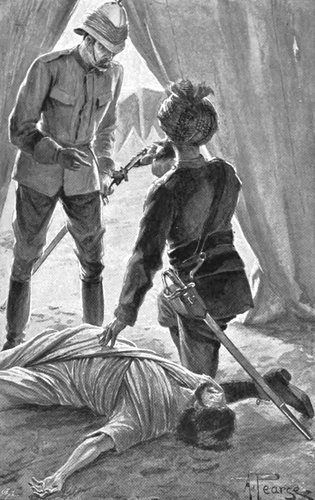

“Never mind. Go back into your tent, and don’t show yourselves, any of you,” returned Dick, sharply. She obeyed without hesitation; but since he had not forbidden her to watch him, she took advantage of a hole in the canvas to gain a view of all that passed. From the sandhill on which the tents were pitched she could see the soldiers in their camp below, gathered round an orator who was haranguing them, while no preparations for starting were visible. She saw Dick march calmly into the throng, elbowing his way through the men with little ceremony, and dislodge the orator forcibly from the unsteady rostrum of biscuit-boxes which he occupied. When she next caught a glimpse of him he was on the outskirts of the crowd again, holding his prisoner by the rags which represented his collar, and propelling him vigorously in the direction of the tents, assisting his progress now and again by a hearty kick. The rest of the troop appeared to have been stupefied by the suddenness of the onslaught, but just as Dick was free of the throng, Georgia saw another man leap up upon a box and call out to his fellows to rescue their leader. The spell was broken, and there was an ugly rush, while weapons were hastily caught up.

“Arrest that man, Ismail Bakhsh,” said Dick, without looking round; “and if he won’t come quietly, shoot him.”

Ismail Bakhsh obeyed in perfect silence, and led his captive up the hill after Dick, the troopers once more making way for him without attempting to use their weapons. Arrived at the summit, Dick paused and looked back.

“Dismiss!” he said, in a sharp, harsh voice such as Georgia had never heard from him before, and the mutineers, understanding the order by a species of intuition, dispersed quietly, while Dick and Ismail Bakhsh passed on to the tent with their prisoners.

“Georgie, what is the matter?” cried Lady Haigh, as Georgia dropped the canvas flap with a gasping cry, and staggered back against the tent pole.

“Only that I have just watched Dick take his life in his hand,” she explained, breathlessly. “For the last ten minutes I have been thinking that I should never see him alive again.”

In Stratford’s tent a hasty and extremely informal court-martial was held immediately for the purpose of trying the two prisoners, and here the management of affairs passed out of Dick’s hands. He was in favour of shooting both men on the spot, as an encouragement to the rest, but Stratford shrank from the idea; and the piteous entreaties of the Ethiopian captain, who pointed out that if such a sentence were carried into execution his life would not be worth a moment’s purchase when he started to return home alone with his troops, were allowed to prevail upon the side of mercy. It was difficult to devise a suitable punishment under the circumstances; but finally the two men were deprived of the semblance of uniform they possessed, and driven out into the desert on foot by the servants, provided with a meagre allowance of bread and water. They would not starve, unless they wilfully remained where they were instead of retracing their steps along the road they had come, but it was probable that they would have an extremely unpleasant experience before they found their way back to the habitations of men.

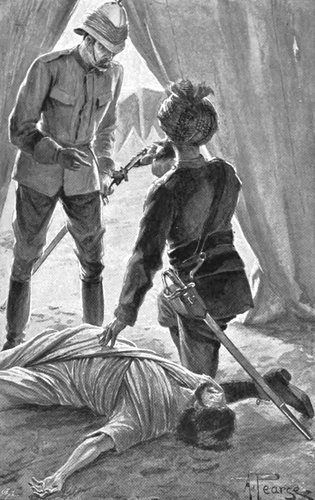

The lesson proved to be a sufficient one, and the troopers, with sullen faces, returned to their duty, imbued with an added respect for Dick and an increased hatred and contempt for their own commander. They made no parade of either of these sentiments during the day’s march, but the net result of them was visible the next morning, when no soldiers could be found. They had ridden away during the night from their bivouac on the outskirts of the camp, leaving their watch-fires alight to deceive any observers, and in his tent the body of their captain, pierced with many wounds.

“A wound for each man,” said Ismail Bakhsh, contemplating the dead man with mingled curiosity and disgust; “and see here, the rebels have left a gift for my lord.”

“See here, the rebels have left a gift for my lord.”

He lifted from the spot where it had been laid at the side of the corpse a long curved dagger, the handle and sheath of which were of silver, curiously chased and encrusted with turquoises. A scrap of paper partially burnt, which had apparently been picked up after being used as a pipe-light and thrown aside, was wrapped round the lower part of the blade, and a few words in Arabic characters were traced upon it.

“‘To the General Dīk,’” read Ismail Bakhsh with interest. “It is the dagger which my lord admired when he saw it worn the other day by one of those forsworn ones. At least they know a man when they see one, evil though they are.”

“You can bring the thing to my tent,” said Dick. “I will keep it as a curiosity. And now, Ismail Bakhsh, we must see this poor wretch decently buried before we go on. You and your men had better perform the proper ceremonies, and we will fire a volley over his grave by way of giving him a military funeral.”

Leaving the scene of the tragedy, he communicated to Stratford his impressions of the state of affairs, and they agreed to minimise as far as possible the importance of what had occurred when in the presence of the ladies. Accordingly, they talked cheerfully of the advantage of being rid of the escort of a mutinous and discontented body of troops, and said nothing of the unwelcome thought which had suggested itself to Dick, that the mutineers might have taken it into their heads to ride on in advance, so as to lie in wait for the caravan at some awkward corner. The body of the unfortunate Ethiopian captain was buried with military honours, and the cavalcade, now much diminished in numbers, took the road again.

The next difficulty that confronted the leaders of the party was caused by the action of the guides, who came to Stratford that evening and begged that he would allow the usual order of the march to be changed for the next few days, so that the journey should be carried on at night, and the necessary halt take place during the hours of daylight. The Mission, they said, was now approaching the region dominated by Fath-ud-Din’s two fortresses, Bir-ul-Malik and Bir-ul-Malikat, and it was all-important that its passage should not be perceived by the watchmen upon the walls. This appeared at first sight very reasonable, and Stratford and Dick, having heard what the men had to say, and dismissed them, found themselves somewhat at a loss as to their answer.

“If we were sure that we can trust these fellows,” said Stratford, “it would be all right, but Jahan Beg warned us against them particularly. Then, again, why didn’t they state when we engaged them that it might be advisable to make night marches for part of the way, at any rate while we are in the sphere of influence of the garrisons of these forts?”

“Oh, as to that,” said Dick, “no doubt they would say that they didn’t bargain for the soldiers mutinying and deserting us, and thought that under their escort we should be safe enough, even in the daytime. But I don’t like this nocturnal idea for two reasons. We should be quite unable to identify the features of the country at night, and they might lead us astray without our discovering it; and moreover, if the mutineers or Fath-ud-Din’s friends should happen to mean mischief, a night-attack on the column as it marched would simply smash us up. We should have more chance in daylight, or even in case of a night-attack on the camp, for the baggage gives us a certain amount of cover when it is properly piled and the beasts picketed.”

“But on the other hand, if the guides are trustworthy, we are doing a very mad thing in rejecting their advice.”

“Quite so; we have a choice of evils. But if you remember, Jahan Beg was of opinion that the fellows ought to be able to take us past the forts without our even coming in sight of them, so that this exaggerated carefulness seems unnecessary.”

“Then you are for going on as we are? It’s an awful risk, North, if things should go wrong.”

“I have more at stake than you have, old man, and you may depend upon it that nothing but the firmest conviction that this course is the safest would make me advocate it. Of course, you boss this outfit, as Hicks would say——”

“Oh, nonsense!” said Stratford. “I am not going to back half an opinion of my own against all your experience. We will stick to our morning and afternoon marches, North.”

The decision thus reached was duly communicated to the guides, and received by them with sulky acquiescence. The next day’s march was uneventful; but the aspect of the country was gradually changing, and becoming more rocky, although it remained as barren and parched-looking as before. The halt that night was made at the foot of a steep cliff, which afforded protection in the rear, while a breastwork of baggage and saddles, arranged in the form of a semicircle, gave some guarantee against a successful attack in front. Again the hours of darkness passed without alarm, but the equanimity of the party was disturbed at breakfast by a domestic misfortune. Rahah, in floods of tears, came to inform her mistress that the white cat was lost. On the journey Colleen Bawn was always Rahah’s special care, travelling on the same mule, and occupying the pannier which contained Miss Keeling’s toilet requisites, and which was balanced by the maid in the opposite one. On this particular morning Rahah had sought her charge in vain. She knew that the kitten was generally to be found by Georgia’s side at breakfast-time, laying a white paw on its mistress’s wrist with dignified insistence when it had reason to imagine itself forgotten; but this morning the tit-bits remained unclaimed on Georgia’s plate. Rahah had searched the whole camp, she said, and Ismail Bakhsh’s son Ibrahim had helped her, but they could not find the white cat; and would the doctor lady request the gentlemen to stop the loading, and set all the men free to look for it? They had sworn to find the doctor lady’s pet if it took them all day to do it, and they knew that the little gentleman (this was the undignified name by which Fitz was invariably known among the servants) would help them.

“I am afraid we can hardly sacrifice a day for such a purpose,” said Stratford, wavering between politeness and a sense of his responsibility as leader, as Georgia looked across at him; but Dick showed no such hesitation.

“Miss Keeling would never think of your doing such a thing, Stratford. To hang about here, of all places, while Anstruther and the servants looked for a lost cat, would be a piece of criminal folly—one might almost say wickedness. We can’t risk the lives of the whole party for the sake of a cat. Here, ayah—take another good look about while we finish breakfast, and if you haven’t found the beast when we’re ready to start, we must leave it behind.”

Georgia’s face flushed as she stirred her coffee deliberately. She had no wish to risk the lives of the whole party by insisting on delay, but it was not Dick’s place to say so for her. It looked as though he had no confidence in her, that he should not allow her even the semblance of a choice, and confidence was what she demanded above all things. It flashed upon him presently, noticing her silence, that he had hurt her, and he bent towards her to say in a low voice—

“I say, Georgie, you don’t mind much, do you? Are you awfully keen on the little beast? I’ll buy you dozens when we get to Khemistan. But you wouldn’t have us waste time now?”

“You have quite put it out of my power even if I wished it,” returned Georgia, coldly; and Fitz, at the other side of the makeshift table, was filled with a sudden and violent hatred against Dick. It was not the first time that this feeling had entered his mind—in fact, it merely slumbered intermittently, and awoke whenever Dick and Georgia had a difference of opinion, no matter which side was in the right. Fitz had no desire to quarrel with Georgia’s choice, for his loyalty was too unquestioning to admit a doubt of her wisdom in the matter; but that the highly-favoured man who was honoured by the love of this peerless lady should be so blind to the grace bestowed upon him as actually to contradict and even to bully her (this was Fitz’s rendering of what he saw) was only an awful illustration of the depths to which human depravity could descend. At such times as this all the boy’s faculties were on the alert to render some service, however great or small, to his lady, which might assure her that even though Major North possessed no due sense of the overwhelming privileges she had granted to him, there were others who still counted it an honour to be able to anticipate her least wish. It is slightly pathetic to be obliged to record that Georgia accepted his good offices without at all appreciating the sentiment from which they sprang—indeed, so ungrateful is human nature that, had she discovered it, she would probably have rejected them with contumely, and poured out the vials of her wrath on the head of the luckless youth who dared to criticise Dick—and that she valued the slightest attention from her lover far above all that Fitz could offer, in spite of the much greater disinterestedness of the latter’s endeavours. But this only proved to Fitz more clearly still her excellence, as exemplified by her absolute loyalty to the man of her choice, and stimulated him to continue to render his unselfish services.

The efforts of Rahah and her fellow-servants to find Colleen Bawn proving ineffectual, the march began at the usual time, although not until after Dick had personally conducted Georgia to the top of the cliff, that she might see whether the kitten had found its way thither; but the rough scramble to the summit and the difficult descent were alike undertaken in vain. Doubtless, said Rahah, with an indignant glance at Dick, the white cat had curled itself up in some cleft of the rocks and gone to sleep, and it would be easy for the men to discover it if they searched systematically, although a cursory look round was useless. But no delay was allowed, and Rahah settled herself mournfully in her pannier, and snubbed Ibrahim whenever he came near her—a course of treatment which, while it failed to irritate him, proved most serviceable in working off her own bad temper.

Important though this storm in a tea-cup was to the two or three persons immediately interested, the leaders of the party had far weightier matters to consider. The march had lasted some two hours and a half when Stratford, who had been riding at the head of the caravan with one of the guides, turned back and joined Dick, whose post, when he was not on duty, was naturally at Georgia’s side.

“What do you think of the look of the weather, North?”

“I don’t like it. See what a dirty sort of colour the sky has turned. I should say we were in for a storm.”

“That’s just what these fellows say. A sand-storm is what they prophesy; but that’s all rot, I suppose.”

“Oh no. We can get up very tolerable imitations of the real thing in these desert tracts, but they are not particularly frequent. However, the guides ought to know; and if they say there’s one coming, we had better look out for some sort of shelter.”

“The guides make out that there’s a ridge of rocks somewhere about which would protect us to a certain extent, but they don’t seem very sure of their ground. The ridge might be any distance between ten minutes’ walk and half a day’s journey ahead of us, from all I can discover.”

“We’ll send young Anstruther and two men on in front to reconnoitre a little, while you and I and Kustendjian see what we can get out of these fellows. Why, where is the child gone? Hi, Ismail Bakhsh, where is the chota sahib?”

With a face as ingenuous as that of the youthful Washington when he resisted the historic temptation to mendacity, Ismail Bakhsh replied that he had last seen the little gentleman at the rear of the column, not thinking it necessary to add that it was at a considerable distance to the rear, and that Fitz was riding in the opposite direction to that in which the column was proceeding.

“Well, we can’t wait to fetch him up from the rear,” said Dick, looking back over the long caravan. “I will ride on and do the scouting, Stratford, while you and Kustendjian cross-examine the guides. It would be just as well to pass the word along for the men to step out a little faster, don’t you think?”

Stratford agreed, and the pace of the caravan was a good deal accelerated in a spasmodic kind of way. Dick and his followers returned from their reconnaissance in a little over half an hour, by which time the gloomy hue of the sky was much intensified, and the air had become quite hazy. Stinging particles of grit were driven against the face as the riders moved along, and sudden gusts of wind, coming short and sharp, now from one point of the compass and now from another, were chasing the sand hither and thither in little eddying whirls.

“We have found the place!” cried Dick, as he rode up. “Pass the word to hurry, Ismail Bakhsh; it’s not much further on. And bring up one of the camels with the tents. We must get up some sort of shelter for the ladies.”

The ordinary dignified pace of the caravan was now exchanged for a helter-skelter mode of progression, which was extremely trying to the mind of Dick, when he saw the confusion which was engendered in the ranks by the haste he had recommended. It was more like a disorderly race than peaceful travelling, and the different bodies of servants were inextricably mixed up.

“What a gorgeous chance for the enemy if they saw us now!” he said to himself. “The only thing is that they are probably just as much taken up with the storm as we are.”

No long time elapsed before the friendly ridge of rocks was reached, and the tent erected under its shelter. Sir Dugald was carried inside, Lady Haigh and Georgia and their maids followed, and the canvas was fastened down tightly. Stratford and Dick, remaining outside, did their best to create some sort of order out of the chaos which surged around them as the servants and baggage-animals came pouring up. There was no time to unload the mules and camels, but they were brought