CHAPTER XIX.

THE VALUE OF A REPUTATION.

“Get the men together while I try a parley with these fellows,” said Stratford to Dick, when he took in the facts of the situation. “They are not our friends the mutineers, at any rate.”

“My lord’s topi,” said Ismail Bakhsh, stepping up with a salute, and offering Stratford his helmet, which he had found caught in a crevice of the rocks. Stratford put it on, and, carrying his riding-whip carelessly in his hand, advanced to meet the strangers, who had remained motionless on their horses since Dick had first caught sight of them.

“Peace be upon you!” he said as he approached them.

“And upon thee be peace!” responded an old man, who appeared to be the leader of the party. “My lord is one of the envoys of the Queen of England to our lord the King?”

“I am temporarily in command of the Mission, owing to the illness of the Envoy,” answered Stratford. “To whom have I the honour of speaking?”

“My lord’s servant is Abd-ur-Rahim, Governor of the fortress of Bir-ul-Malik for our lord the King.”

“Not for the late Grand Vizier, Fath-ud-Din, then?”

“How should that be so? My lord knows that another now holds the King’s signet. Surely his servant only retains his office until he be confirmed or superseded in it by orders from Kubbet-ul-Haj. But the only orders he has received as yet have concerned the Mission of the English Queen, and they have commanded him to do all in his power to help it, and to facilitate its return journey.”

“Then the orders have arrived in the nick of time,” said Stratford. “A little assistance will be of great use to us in our present circumstances. Our baggage-animals were alarmed by the storm, and are scattered about, and if your soldiers would help us to get them together again it would be a great boon. But will you not dismount and eat and drink with us, Abd-ur-Rahim? We have but little to offer, yet it is our delight to share it with a friend.”

“Nay, but my lord and all his company shall eat and drink with me,” was the hospitable reply. “In Bir-ul-Malik there is room for the whole number, and they shall rest in the fortress this night in peace, and refresh their souls before starting again on their journey. I will send out my young men to seek for the camels of my lord, and in the morning his caravan shall be as great as when he left Kubbet-ul-Haj a week ago.”

“Yet let Abd-ur-Rahim first honour our poor tents by condescending to eat bread and drink water with us,” urged Stratford.

Again the old man shook his head. “Not so, my lord. Surely when my watchmen cried from the towers that there was a great company out on the plain, fleeing towards the rocks for shelter from the storm, and I knew that they must be the servants of the English Queen, I vowed a vow that I would neither eat bread nor drink water until I had brought the Englishmen into my house, that they might rest themselves and be refreshed at my table, and afterwards depart in peace.”

“And how did you know that we were the servants of the English Queen?” asked Stratford, endeavouring, with considerable success, to exhibit in his tones no trace of suspicion, but merely a natural desire for information.

“The orders I received had warned me of the approach of my lord and his servants,” replied Abd-ur-Rahim, guilelessly, “and the watchmen told me that among those whom they saw were men with strange head-gear, such as our people who have journeyed into Khemistan have seen the English lords wear. But will not my lord make haste to call his young men together, and bid them follow him into the fortress? The feast is being prepared, and the best rooms are ready for my lord and his servants and his household, and only the guests are wanting.”

“I must take counsel with my friends before I accept your kind invitation,” said Stratford. “We are in haste, and it may be that we cannot venture to lose even the remaining half of this day’s march.”

“Nay, my lord,” exclaimed Abd-ur-Rahim, in the eagerness of his hospitality, “far be it from me to compel any to become my guests by force—and yet, sooner than allow my lord to depart without honouring by his presence my humble roof, I would command my young men to bring him and his servants to my dwelling whether they would or no.”

“One might indeed say that yours was a pressing invitation, Abd-ur-Rahim,” said Stratford, smiling good-humouredly as he turned to go back to the rest; but there was no smile upon his face when he reached them.

Dick stepped forward to meet him, and they walked a few paces aside, out of earshot of the little band of servants whom Dick had posted in such a way as to protect the tent and the remaining baggage-animals.

“Well?” asked Dick, eagerly.

“Oh, he’s a deep one! He means to get us up to the fort by hook or by crook, and the only question is, shall we go peaceably or wait for him to take us?”

“He has been looking out for us, then?”

“Undoubtedly. He says he was warned of our approach by orders from Kubbet-ul-Haj. Now you know that the King and Jahan Beg never anticipated that we should halt anywhere near Bir-ul-Malik, so that the orders can’t have come from them. They must have been sent by Fath-ud-Din or some of his people, and very likely Abd-ur-Rahim has had additional information since then from the mutineers. We can’t hope that he is merely hospitable and friendly. If we go into the fort, we go with our eyes open.”

“But hasn’t he showed his hand at all?”

“Not a bit. He is all blarney and butter, only anxious for the honour of our presence and so on, but he means business.”

“But we can be all blarney and butter too, and merely regret our inability to pay him a visit, and pass on. If he doesn’t try force, it’s quite evident that he hasn’t any to try. He is doing his best to allure us to put ourselves into his power, trusting in the simplicity evidenced by your childlike and bland demeanour, and there is no doubt that if he once got us inside the fort we should be in something like a hole. But as it is, we can merely bow and say good-day.”

“I’m afraid not, North. It is Abd-ur-Rahim who has the cards up his sleeve this time. When I stood out there on the plain talking to him, I could see further than you can from here. He is very sweet and smiling, and he doesn’t want to make a show of force if he can do things pleasantly; but behind these rocks here he has men enough stationed to account for us all five or six times over.”

“Then we are trapped!” said Dick, grimly, drawing his sword half out of its scabbard and feeling the edge. “Well, better here under the open sky than between stone walls. We can give a good account of two or three times our number, posted as we are here, and they won’t get much change out of us.”

“North, you bloodthirsty villain! Think of the poor women and the Chief, and don’t talk of running amuck in that cast-iron way.”

“Don’t I think of the women? Do you imagine I am made of stone, Stratford? My first shot is for Georgia, and after that—well, I suppose I shall run amuck.”

“Draw in a little, old man. That way madness lies. Keep cool, and listen to me for a moment. Since I have no one specially to look after, it may be that I am able to see things more calmly than you are. At any rate, it strikes me, leaving out of sight that ferocious idea of yours, that if we were cut to pieces we could do no possible good to any one—whereas if we accept Abd-ur-Rahim’s overtures in a friendly spirit, and go with him, keeping possession of our weapons and holding together, we might spot a chance of escape, and at any rate we should be no worse off than we are now. If I were you, I should be thankful to keep clear of murder a little longer.”

“Don’t talk to me!” said Dick, savagely. “You have not my reasons for anxiety.”

“Nor your reasons for prudence, either. Look at things quietly, North. I am certain this old fellow is not quite on the square, or he wouldn’t refuse to eat and drink with us; but I don’t think his intentions are necessarily murderous. If they were, he could easily have wiped us all out here and now, without taking the trouble to get us up to the fort. My own impression is that he means to hold us as hostages for Fath-ud-Din’s safety. If that is the case, we shall certainly be in no danger. It will only mean a slight delay, for when our Government find out from Hicks that we ought to reach the frontier soon after him they will send to inquire after us if we don’t turn up.”

“But supposing Abd-ur-Rahim’s intentions are murderous after all?”

“Then we shall end up with a big fight, I presume, and the result will be much the same in the fort as it would be here. Come, North, don’t let us give up hope too soon. If the worst comes to the worst, the ladies have revolvers and can use them—and I don’t know two women anywhere who would be more certain to use them if it was necessary. Just you go to the tent and tell them quietly the state of affairs, while I inform Abd-ur-Rahim that we accept his offer of a night’s lodging. Then you and Kustendjian had better come and be presented. We will do everything in style, and with the most lively imitation possible of perfect confidence. The great thing is to avoid giving them the slightest excuse or opportunity of depriving us of our arms.”

Doggedly and unwillingly Dick took his way to the tent, while Stratford returned to Abd-ur-Rahim, who had remained stationary, with his immediate followers, during the colloquy. But he had profited by the interval to draw closer the cordon of armed men of whom Stratford had caught sight behind the rocks, and it was evident that, if such a fight as that contemplated by Dick had taken place, there would have been no possibility of escape for any member of the English party.

“I must apologise for keeping you waiting so long, Abd-ur-Rahim,” said Stratford, as he approached. “My friend is a great soldier, and very zealous in carrying out the business with which we are charged. He feared to lose even this half-day’s journey; but I have succeeded in making him see that it is the act of a wise man to accept rest and refreshment whenever it is proffered by one worthy of respect.”

“Truly the wisdom of my lord is great!” responded Abd-ur-Rahim, a smile of gratification curling his white moustache, while an officer behind him muttered to a companion some words in Ethiopian which sounded to Stratford like, “It is not so easy to hoodwink the soldier as the man of many words,” a remark which was distinctly unjust to the listener. He made no sign of having heard it, however, but went on speaking to Abd-ur-Rahim in Arabic.

“There is only one thing I should like to say before we accept your hospitality, Abd-ur-Rahim. It is our habit to guard with great jealousy the women of our party. I believe your own custom in Ethiopia is much the same, and you will not, therefore, take it amiss if we surround them closely while on our march with you?”

“Surely not,” responded Abd-ur-Rahim, somewhat puzzled. “The customs of my lord’s land are even as our own, and his care for the household of his master gives the lie to the shameless tales that have been told me as to the habits of his nation. I have even heard it said that in Khemistan the women of the English go about unveiled!”

Stratford was saved from the necessity of either confirming or denying this tremendous accusation by the approach of Dick and Kustendjian, whom he presented formally by name to Abd-ur-Rahim, mentioning the rank held by each in the Mission. The old man looked at them in some surprise.

“Are these all the English that are with my lord?” he asked. “I heard that he had three white men under him.”

“There is one other,” said Stratford, “a youth; but we have seen nothing of him since the storm broke upon us, and we fear that he has missed his way and been lost.”

“Let not my lord be troubled about the young man,” said Abd-ur-Rahim. “The storm did not last long enough for him to have come to any harm. Surely he has but taken shelter in some cave or hollow of the rocks, and my young men shall go in search of him, and bring him again to my lord.”

Having acknowledged this offer in suitable terms, Stratford and the rest returned to superintend the arrangement of their party under the new conditions. The tent was taken down and packed on its camel again, the mules were harnessed afresh to the litter which carried Sir Dugald; the ladies, mere masses of white linen, were helped to their saddles; the diminished cavalcade of baggage-animals was ranged in order, and the column was ready to start. Stratford considered it only polite and expedient that he should ride beside Abd-ur-Rahim, much to the annoyance of Dick, who brought up again the memory of the murdered Macnaghten, and urged sotto voce that if any one’s life was to be risked, Kustendjian’s was the one that could be best spared. Stratford laughed at the idea, and retained his place, and the other two rode on either side of the litter, with the ladies following close behind them, while Ismail Bakhsh and his men formed a modest bodyguard. The household servants and the few muleteers and camel-men who had not been scattered by the stampede followed with the baggage-animals, and before and behind and all around, when the column had advanced into the open plain, came Abd-ur-Rahim’s wild soldiery. A few stray mules and camels were picked up by the way and added to the cavalcade, and presently the procession wound round a spur of the cliffs, and began to ascend the winding road which led up to the hill-fortress of Bir-ul-Malik, the stronghold of Fath-ud-Din.

The town itself was small in extent, and it was evident that the garrison formed the larger proportion of its inhabitants, for the rock-hewn streets were almost deserted when Abd-ur-Rahim passed through the gate with his guests. The town-walls surrounded a considerable area on the summit of the cliff, and this in its turn sloped upwards at its further extremity, on which was erected the citadel, which thus commanded the town on one side and a sheer declivity on the other. Towards this fortification the procession made its way, Dick glancing grimly at the tortuous streets and massive walls of the town as he rode, and muttering to himself that he and his party were in a trap which would take a good deal of getting out of. Passing in at the gate of the citadel, they found themselves in a large courtyard, above which rose a pile of buildings, constructed on and in the sloping face of the rock, the roofs of those lower down forming terraces by which the higher ones could be approached. The lower range of dwellings appeared to form the quarters of the garrison and servants, and those next above them the abodes of the officers, while the highest pile of buildings was evidently intended as the residence of the governor of the city. It was in this building, Abd-ur-Rahim intimated, that he had caused a lodging to be prepared for the illustrious English party; and Stratford, while appreciating the honour done him, felt that he could readily have dispensed with it, since escape would be out of the question save by passing all the lower dwellings and the inner and outer circuit of defences, the only alternative being the possibility of finding some means of descending the precipitous cliff on the other side.

It was necessary to dismount in the courtyard, and to ascend to the Governor’s palace by a winding path cut in the rock and varied by several flights of steps. There was considerable difficulty in conveying Sir Dugald’s litter up this path, and what remained of the luggage had also to be carried up piece by piece, at a large expenditure of time and trouble. When the palace was once reached, however, there was no fault to find with the rooms allotted to the Mission. It was evident that they had remained uninhabited for some time, and they were rather dirty, rather dilapidated, and particularly bare of furniture; but they were large and airy, and, as Stratford and Dick noticed with great satisfaction, the apartments appropriated to the ladies, which had formed part of the original harem, could only be approached by a passage from their own portion of the building. Behind, they looked out on a terrace formed by the top of the ramparts, beneath which the cliff fell steep and unbroken to the desert below. It was an alarming experience to come suddenly to the brink of this declivity, from which the unwary were protected merely by a crumbling parapet, and Rahah only consented to contemplate it when standing at least six yards from the edge, and holding firmly to her mistress’s clothes.

Returning from the terrace into the harem, Georgia began to examine the waifs and strays of luggage which had been cast up with her on this hill-top. Sir Dugald had been conveyed into one of the inner rooms, and Lady Haigh, with the assistance of Chanda Lal, was engaged in making him comfortable. In the large hall, into which the other rooms opened, lay a confused heap of boxes and cases, just as they had been left by the porters who had carried them in.

“Let us see what we have, Rahah,” said Georgia to her handmaid. “You had my dressing-case and my small medicine-chest on the mule with you, so they are safe, at any rate, and your own clothes too. That box there has books in it, I know, and here are our folding-chairs. I don’t see any of my clothes—any of my own things at all, in fact. I shall have to borrow some from Lady Haigh, for I see that two of her tin boxes are there. Those cases are Sir Dugald’s, of course; and now there are only these two great boxes left, marked with my name. What can they have in them? Nothing very useful, I’m afraid—no dresses, at any rate. Just borrow a hammer and chisel from Chanda Lal, Rahah. He was opening a packing-case a minute ago.”

Returning quickly with the desired implements, Rahah forced open part of the lid of one of the boxes.

“Medical stores!” said Georgia, bringing out a packet of cotton-wool, and a tin case containing a roll of prepared india-rubber. “I might be going to start a dispensary up here. Well, we are satisfactorily provided with medicines and surgical appliances, at any rate. Now the other box, Rahah. I only wish there was the slightest possibility of finding some of my clothes in it.”

But no. Rahah drew back with a scream when she plunged her hand into the mass of crumpled paper which guarded the contents of the box; and Georgia, guessing the state of affairs, brought out a huge, carefully-stoppered bottle, containing a gruesome-looking object swimming in a muddy yellow fluid.

“The collection!” she said, disdainfully. “And of course that particularly detestable snake turns up first of all! Well, Rahah, we are in a nice plight, with no clothes or fancy-work or sketching materials, but with a good many of those creatures to amuse us instead.”

Rahah’s countenance expressed unutterable disgust, and her mistress was not proof against a modified feeling of the same character, for it is the reverse of agreeable, even for a highly qualified lady doctor, to find oneself reduced to a single dress, and that a riding-habit. But while this small although sufficiently unpleasant matter was occupying the minds of Georgia and her maid, Stratford and Dick were experiencing a very bad quarter of an hour in their part of the building. When their host left them they had occupied themselves in sorting the few possessions that remained to them; but while they were in the midst of this somewhat melancholy process, Abd-ur-Rahim returned, accompanied by two or three of his officers.

“Is my lord graciously pleased to be contented with the accommodation afforded by my poor house?” asked the old man.

“I am sure we could ask nothing better,” returned Stratford, pleasantly.

“That is well, seeing that it will now be my lord’s abode during certain days,” said Abd-ur-Rahim.

“How is that?” asked Stratford. “You offered us merely a night’s lodging, and we accepted it.”

“True; but a man of my lord’s wisdom will not need to be reminded that it is only fools who allow the gifts of destiny to slip through their fingers. My lord and his companions have been brought into my hand, and here they will remain so long as our lord Fath-ud-Din is kept in prison at Kubbet-ul-Haj.”

“Thank you. There’s nothing like knowing what one has to expect. How many years do you intend to entertain us here?”

“That depends upon another matter. The liberation of Fath-ud-Din hangs upon the treaty that my lord holds, for if that is destroyed, our lord the King is free to do as he will, and the treaty, on account of the means by which it was gained, he finds disgraceful and irksome to him.”

“Show me the King’s mandate demanding the surrender of the treaty,” said Stratford, quickly.

Abd-ur-Rahim shook his head.

“My lord knows that there are certain services that a man may render to his sovereign for which no orders can be given beforehand, although they may be richly rewarded when performed,” he said. “Of such a kind is this matter of the treaty.”

“Don’t you wish you may get it?” asked Stratford, aware that Dick’s fingers were gripping his revolver.

“My lord must know that we shall get it. We have but to compass the death of my lord and his companions, and the treaty must be found; but we would fain not shed blood. Let my lord tell his servant where the treaty is hidden.”

“I absolutely decline to say,” returned Stratford.

“Then we must search my lord’s baggage.”

“You can search where you like, but you cannot make me tell you where the treaty is. I presume you do not intend to search the baggage of the ladies?”

“Nay, my lord! What hiding-place is so safe or so probable as among a woman’s belongings? But there need be no search if my lord will only tell what he knows. Did he bring the treaty into the fortress with him?”

“I refuse to say. One word, Abd-ur-Rahim. There can be no idea of searching the ladies’ things. You may ask what questions you like, but the ladies must have notice beforehand, and it must be in the presence of one of us, or—well, whoever goes into the harem, you will not be alive to do it.”

“My lord need have no fear. He may go now and bid the women prepare for my coming. I will but question them, and believe what they say, for the English always tell the truth. I would accept the word of my lord even now, if he could assure me that he had not the treaty with him when he entered the fortress.”

There was some eagerness in the old man’s tone, as though he found his task distasteful, and would have welcomed this chance of dispensing with the performance of it; but Stratford shook his head.

“I can say nothing. Stand at the door, North, while I go in to warn the ladies. And keep cool. Cheek may possibly bring us through this fix yet, as it did through the other.”

With a frowning brow, Dick took up the position indicated, and Stratford entered the passage and knocked at the door. Georgia looked up from her doleful examination of her possessions as he came in.

“We are trying to discover what we have saved from the wreck of our fortunes,” she said, lightly. “But what is the matter, Mr Stratford? Does your venerable old friend intend to murder us after all?”

“Not unless he is obliged,” returned Stratford; “but it may come to that yet. He means to get hold of the treaty. Fath-ud-Din seems to think that if he enables the King to destroy it, he will be restored to power. I don’t think the King is in the plot at present, but far be it from me to say that he wouldn’t come into it with a good grace if he got the chance.”

“And you want me to hide the treaty?”

“Certainly not. By no manner of means. I merely came to tell you that Abd-ur-Rahim insists on questioning you and Lady Haigh as to whether you know anything about it. He will come in here when he has finished ransacking our place, so put your burkas on again, please.”

“But, Mr Stratford, where is the treaty?”

“Here,” said Stratford, exhibiting the front of his coat, “in a pocket which my bearer and I contrived for it. You see, it goes between the cloth and the lining, and is sewn in. It is rolled up so tightly that it does not show at all under ordinary circumstances; but if they search me, they are bound to find it immediately.”

“And what then?”

“I can’t give it up, of course, so that if they attempt to search us, we must show fight. We must only hope they won’t, for our opposing the idea would arouse suspicion at once.”

“If they have any sense whatever, it is the first thing they will do,” said Georgia, promptly. “No, Mr Stratford, I am not going to allow you and Dick to run such a risk, and perhaps bring destruction upon us all. Give me the treaty, and I will hide it.”

“And transfer the risk to yourself? Now, Miss Keeling, do you really think me capable of doing such a thing?”

“There will be no risk whatever. I have an idea. Take off your coat, Mr Stratford—quick!” with a stamp of the foot—“there is no time to lose. Give me those scissors, Rahah, and thread a needle with grey cotton. That’s it; now sew up that slit as neatly as you can.”

“What are you going to do?” inquired Stratford, standing helplessly by in his shirt-sleeves, while Georgia was rolling the fateful parchment into the smallest possible compass, and Rahah stitched up with marvellous rapidity the yawning hole in his coat.

“Never mind, for I won’t tell you. You are to know nothing. There is your coat, Mr Stratford. Keep Abd-ur-Rahim outside for two minutes, and then let him do his worst.”

Half-reluctant and wholly perplexed, Stratford allowed himself to be gently impelled in the direction of the door, and went out, to find Dick, still on guard, protesting vehemently that he would never allow himself to be searched, and that the first man that laid a finger on him with that purpose in view would have little opportunity for repenting his rashness afterwards. Perceiving at once that his friend guessed he had the treaty upon him, and was endeavouring to divert suspicion to himself, Stratford proceeded, not without a little malicious pleasure in the circumstance, to cut the ground from under Dick’s feet by remarking calmly—

“Keep cool, North; we are prisoners, though we were seized by a mean trick, and we must submit to the treatment our jailers think fit to inflict upon us. Abd-ur-Rahim”—he turned with dignity to his too hospitable host—“we are your prisoners. As to the means by which you induced us to put ourselves in your power I say nothing. Still, I ask you as a gentleman, is this insult necessary?”

“By no means,” returned Abd-ur-Rahim, promptly. “If my lord and his friends will give their word that they have not the treaty about them, they shall not be touched.”

To the utter stupefaction of Dick, Stratford at once gave the required assurance, which was repeated by his friend and Kustendjian. Some demur was made as to accepting the word of the latter, on the ground that he was not an Englishman; but on Stratford’s volunteering the assurance that he was speaking the truth, his statement also was considered satisfactory.

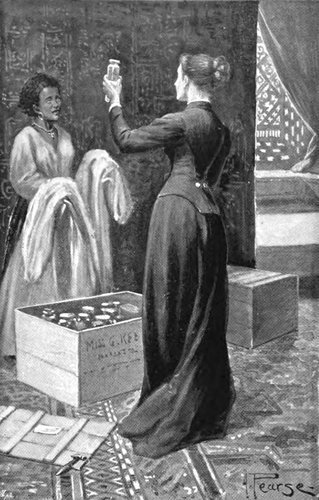

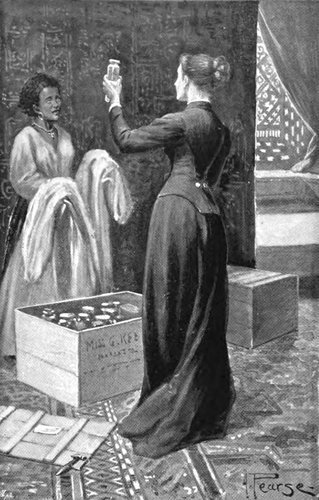

In the meantime, Georgia and her maid were not idle in the inner room. The moment that the door had closed behind Stratford, Georgia flew to the box which contained the collection, and drew out the bottle enshrining the historic snake. The roll of prepared india-rubber from the case of medical stores was the next requisite, and, unfastening it, she made Rahah cut off a piece a little longer than the treaty in its rolled-up form, and wide enough to wrap round it twice. When the roll had been made as tight and smooth as possible, she tied up the ends very securely.

“Now, Rahah, take off the bladder from the top of that bottle as carefully as you can. Don’t break it, whatever you do. Now get the cork out. Dig it out with the point of the scissors if it won’t come easily; we mustn’t use a cork-screw. Turn your head away if you don’t like the smell. There,—what a good thing that the spirit has sunk a little!” She dropped the roll containing the treaty into the great bottle, in the midst of the coils of the snake, replaced the cork, tied the bladder over it again, and, holding the bottle up, looked at it critically. The effect was perfect. The dull-brown of the india-rubber wrapping combined with the bolder tones of the serpent’s skin and the unpleasant yellow of the spirit so completely, that scarcely a trace of the intruder was perceptible even to her practised eye.

The effect was perfect.

“So far, so good. Now on with our burkas, Rahah. That’s right, put the bottle back into the box. There is a smell of the spirit about. Knock over that bottle of camphor and break it. Oh, they are coming! Kneel down, Rahah, and be nailing the cover on the box in a most tremendous hurry.”

Rahah entered into her part with keen delight, jerked the camphor-bottle to the floor with her elbow, and jumped up with a most artistically guilty start when Dick and Stratford entered with the four Ethiopians, while Georgia dropped the hammer with a clatter on the stones.

“What is in that box which the women are nailing up?” demanded Abd-ur-Rahim, sharply, while the faces of his followers betrayed much excitement, not unmixed with triumph.

“Do they really want to know?” asked Georgia, with something like pity in her tones, when the question was translated to her. “Well, I will show them if they are so anxious to see it.”

Lifting the lid, she drew out with one hand the bottle containing the snake, and with the other one which enclosed a very evil-looking deformed frog, and held them out to the inquisitors, who recoiled precipitately.

“They are the devils which obeyed the English doctor who was carried off by Shaitan from his house at Kubbet-ul-Haj!” was the murmur which went round.

“There are plenty more in the box,” said Georgia, cheerfully. “You can unpack them for yourselves if you would like to look at them; only I would advise you for your own sakes to take care not to break the bottles.”

“Is it true that if the bottles were opened the devils would get loose?” asked one of the E