CHAPTER XXII.

A SILENCE THAT WAS GOLDEN.

Although she would not for the world have allowed either Rahah or Khadija to discover the fact, Georgia was conscious of a distinct sense of shrinking as she rode under the gateway of Bir-ul-Malikat, after seeing Abd-ur-Rahim start on his homeward journey with young Yakub among his followers. The place was less of a fortress, and more of a country seat, than Bir-ul-Malik; but the high walls which surrounded the grounds of the great house, and about which a number of smaller buildings and huts were clustered, were quite capable of defence, and the assemblage of men visible about the gate and courtyard showed that a respectable garrison could be collected in time of need. Still, the fortifications were not of such a character as to be able to stand a protracted siege, and Georgia guessed what was indeed the truth, that while they were useful to withstand the sudden raid of any marauding border tribe, who might be supposed to be swayed by the hope of plunder more strongly than by superstitious fear, the real bulwark of the place was Khadija’s reputation as a sorceress. Here she was supreme, and her fame protected alike her precious charge and the servants and labourers who formed the little colony. When she had once for all secured the transference of Jahan Beg’s rights in Bir-ul-Malik to her master, by diverting the water-supply, she had removed from her path the only enemy on whom the universal belief in her supernatural power for ill had no effect, and who had been able to keep an eye on her doings. Every man and woman in the place was bound to Khadija’s service both by interest and by fear, and Georgia felt that it was indeed well that Abd-ur-Rahim had insisted on receiving her son as a hostage before he would intrust his prisoners to her tender mercies.

Dismounting from their steeds in the inner courtyard of the great house, where a number of slave-girls were gathered to stare at them, the new arrivals were led by Khadija into the rooms which she had promised them, and which, as Georgia was delighted to find, looked out on the desert in the direction of Bir-ul-Malik. After a short interval to allow them to arrange their possessions and to remove a little of the sand of travel, the old woman came to fetch them, and led them through the rambling, half-deserted house to the opposite wing. Everything in the rooms through which they were conducted spoke of vanished wealth and a gorgeous past. The divans were covered with rich silks, now faded, torn, and dirty, and costly ornaments of European manufacture stood broken and tarnished in corners. It was evident that Fath-ud-Din’s ambitious plans for his daughter’s future had not impelled him to keep her present abode even in tolerable repair, while it was not difficult to discern that Khadija cherished a strong preference for muddle and dirt over cleanliness and order. The state of the passages and of the bedrooms opening from them was extraordinary—they seemed to be filled both with the dust and with the rags of ages; while in the innermost room of all, and therefore the one with the smallest allowance of air and light, was to be found the jewel enshrined in this sorry casket, Fath-ud-Din’s daughter Zeynab, the destined bride of Antar Khan.

“This is my Rose of the World, O doctor lady,” said Khadija, when she had led Georgia into the dark close room, and as she spoke she indicated a small form crouched among a heap of cushions on a broken bedstead. It was so dark that there was no possibility of seeing anything distinctly.

“Get up on that chest, Rahah, and open the lattice a little way,” said Georgia; and as the girl, with a vigorous wrench, forced open the small high window, which moved so stiffly that it was evident it had not been touched for years, the light disclosed a very white little Rose indeed, with a face drawn with pain, and grimed and blistered with crying. The child (she could not have been more than ten) was lying in an uncomfortable cramped position, with the injured foot fastened down to one of the legs of the bedstead. This was Khadija’s latest idea of the way to reduce a swelling. Before saying anything, Georgia stooped and cut the cord, replacing the foot gently on the cushions, but the slight movement drew an uneasy little cry from the patient.

“Who are these people?” she demanded fretfully of Khadija, trying to arrange the folds of the dirty wrapper she was wearing into some semblance of dignity. “I do not want visitors when I cannot put on my best clothes. Why hast thou brought these women here, O my nurse? Who are they, I say?” sharply.

“It is the great doctor lady, who will cure thy foot, my dove,” replied Khadija, somewhat shamefacedly.

“The Englishwoman?” exclaimed the child, starting up and glaring at Georgia with eyes like those of a hunted stag. Then, sinking down again, she burst into a storm of angry sobs, striking Khadija passionately when she tried to calm her. It was useless for Georgia to speak, and equally useless for the old woman to entreat her Rose, her dove, her eyes, her soul, her Queen Zeynab, to be quiet and let the doctor lady look at her foot. The sobs continued with unabated violence, mingled with torrents of vituperation directed at Khadija, and the child fought like a wild cat when any one attempted to touch her.

“Leave her alone,” said Georgia, with an imperative gesture, to Khadija; “come here, and let her have her cry out. Now tell me what you have been saying to her to make her afraid of me.”

“Nothing, O doctor lady—nothing, in the name of God! It is only that the maiden fears the face of strangers.”

“That would not account for her terror on finding out who I was. Speak, Khadija, and tell the truth, or I leave the house at once.”

Terror-stricken by the threat, the old woman mumbled out an explanation, which Rahah translated to her mistress.

“She says, O my lady, that since she heard you were at Bir-ul-Malik she has frightened the child with your name. When she was going to try a new medicine, or to hurt her at all, she would say, ‘If you cry or struggle, I will send for the cruel English doctor lady, who will cut off your foot in little pieces,’ and the child was quiet at once.”

“That is quite enough,” said Georgia, observing that Zeynab, guessing that the rest were talking about her, had hushed her sobs in order to try to hear what they were saying, and she returned to the side of the bed. The sobs began again at once, but Georgia laid a firm hand on the child’s shoulder and signed to Rahah to interpret for her.

“When you have quite finished crying, Zeynab, you can let me know, and I will show you something I have got here.”

The sobs continued for a minute or two with equal violence, but presently they slackened a little, and Zeynab inquired brokenly, “What kind of thing is it?”

“Something you will like to see,” said Georgia; and Rahah added on her own account as she translated the words: “The doctor lady says so, and the English always tell the truth.”

“Do they?” asked Zeynab, with interest. “I thought they were very bad people.” She had ceased to sob, but was too proud to ask for the sight she had been promised, and Georgia took something out of her bag, and waited. More from habit than from any expectation of making use of it, she had slipped in with her instruments a German toy which she had found very useful in winning the friendship of children in her old hospital days, and which had proved a source of great delight to Nur Jahan and the other women in the Palace at Kubbet-ul-Haj. It was carved in wood, and represented a cock standing on a barrel. The barrel contained a yard-measure, and when the tape was drawn out the bird flapped his wings, faster or slower according to the rapidity of the movement.

“What is it?” inquired Zeynab at last, looking curiously at the cock, her interest stimulated by the doctor’s silence. For answer, Georgia pulled out the tape, and the child gave a shriek of wild delight.

“Wonderful, wonderful!” she cried. “Is it alive?”

Rahah explained that the bird was merely one of the marvels of the white people, and Zeynab, after a somewhat timid approach, ventured to pull the tape for herself. Then she was fairly won, and screamed with pleasure as the cock flapped his wings for her. Not to make the wonder too cheap, Georgia reclaimed it after a short time; but the ice was broken. Zeynab lay back on her cushions and looked at her musingly.

“Art thou really a woman?” she asked at last.

“Yes. What else could I be?” asked Georgia, smiling.

“I thought thou wert perhaps a man,” said the child, shyly; and Georgia felt devoutly thankful that Dick was not there to hear her. “Shall I tell thee why, O doctor lady?” she went on, then turned suddenly to Khadija. “O my nurse, I am thirsty. Bring me some sherbet.”

“One of the slaves shall prepare it for thee, my soul.”

“No, there is no one who makes it as thou dost. Fetch it for me, O my nurse, or I shall scream.”

With a very bad grace Khadija complied with the imperious command, and hobbled out of the room. The moment she was gone, Zeynab took a folded piece of paper from beneath her pillow and laid it in Georgia’s hand.

“There!” she said, with a radiant smile. Georgia unfolded the paper, and found it to contain a wretched native print, vile alike in drawing, colour, and intention, and purporting to represent an English ball-room. Some resemblance between the open coat and cotton blouse which Georgia wore with her riding-skirt, and a man’s dress-coat and shirt-front, had struck the child, and led her to the conclusion that Georgia was a man.

“I see what you mean,” said Georgia, whose one glance at the print had filled her with loathing; “but, Zeynab, this is not a very pretty picture for you to have. If you will give it to me, I will find you a book with several pictures in it instead.”

“Give me the book first,” was the prudent answer, as Zeynab reclaimed her treasure jealously. “This is all I have. What are thy pictures like, O doctor lady?”

“There is one of the Queen of England and many of her family,” said Georgia, thinking of some odd numbers of illustrated papers which had thus far survived wonderfully the various vicissitudes of the Mission. “I might even find you two or three books if you will be good and let me look at your foot.”

“Oh, my foot!” Zeynab’s face was pursed up once more in readiness to cry. “It hurts so dreadfully, and Khadija said thou wouldst cut it off.”

“Not if I can possibly help it, I promise you. Will you be a brave girl, and let me look at it quietly? I don’t mind your crying out if I hurt you very much; but you must not struggle, and I will be as gentle as I can.”

“But why should I be hurt? I am Queen Zeynab.”

“Because I must hurt you a little now if you are to get well afterwards. If you are queen here, show it by being braver than any one else would be. I am treating you like a grown-up person, Zeynab, not like a baby.”

“It is well,” said Zeynab, with a frightened little smile. “Thou wilt not cut my foot off bit by bit?”

“Certainly not. If I should have to cut it off, I will give you something to prevent your feeling it at all, so that you won’t even know that it is being done; but I hope it will not be necessary. Now let me see it.”

With great bravery the child allowed her foot to be disencumbered of the mass of dirty rags in which it was enveloped, and lay still with compressed lips while Georgia made her examination. The theory which the doctor had formed on hearing Khadija’s report she saw at once to be the correct one. The splintered bone was accountable for the swelling, and would have induced mortification if it had remained much longer in the wound. The foot was in a frightful state, but there was still just a possibility of operating with success. The operation must be undertaken at once, Georgia decided, if the limb was to be saved, and she turned to Rahah to tell her to get out the necessary anæsthetic. The movement, slight as it was, gave a jerk to the rickety bedstead, which communicated itself to the wounded foot, and forced a moan of pain from the child’s lips. Almost simultaneously with the sound, Khadija precipitated herself into the room with a suddenness which suggested that she must have been listening at the door, and seizing Georgia by the shoulders, thrust her violently away from the bed and to the other side of the little room.

“What art thou doing to my child?” she demanded, standing between the doctor and Zeynab, who was sobbing and wailing with the pain of the rough jar which the impetuous onslaught had caused to her foot. “Answer me, O doctor lady! I sent for thee to cure her, and wouldst thou torment her when I am not by?”

“It is thou who art hurting me, O my nurse,” moaned Zeynab. “The doctor lady did but shake me a little, but thou hast killed me. Go away, and let the doctor lady do what she likes.”

“What! has the doctor lady bewitched thy heart away from me already?” cried the old woman, turning upon her. “Ah, wicked girl, what hast thou there?” and she pounced upon the vile daub which was as good as a whole art gallery to Zeynab, and tore it to pieces. “Have I not forbidden thee to see or hear anything of the evil doings of the wicked white people?”

“I hate thee!” screamed Zeynab, flinging herself upon her nurse, and attacking her with all her might. “The white people are good, and thou hast torn my picture. I love the doctor lady, but thou art a pig!”

“Hush, Zeynab, you will make your foot worse,” said Georgia, interposing between Khadija and her charge. “I am going to give you something that will keep you from feeling pain, and then I hope I shall be able to do you some good.”

“Nay,” cried Khadija; “wouldst thou steal away the child’s soul under pretence of saving her pain? I know thee, O doctor lady, and thou shalt never shut up my Zeynab’s soul in a bottle with snakes and devils and unclean animals. I have heard of thy doings, and of the demons thou hast to serve thee, and how thou dost steal souls that thou mayest make them work evil at thy will. Thou shalt not charm my Zeynab’s soul away to imprison it with them.”

But it only needed this to determine Zeynab immediately in favour of the anæsthetic.

“Shut up my soul in a bottle?” she exclaimed, with eager interest. “But thou wilt not keep it there always, O doctor lady? I should like it for a little while, but not for long.”

“I couldn’t put your soul in a bottle if I wanted it there,” said Georgia, laughing; “but I promise you that I won’t keep you without it longer than I can help.”

“I tell thee thou shalt not use thy vile drugs on the maiden,” declared Khadija stoutly, as Rahah began to get out the necessary implements.

“Then how am I to perform the operation?” asked Georgia.

“I will call two of the slave-women, and they shall hold the child quiet.”

“O doctor lady, thou wilt not let her bring them to hold me down?” entreated Zeynab piteously. “They hurt so dreadfully.”

“Certainly not. I am in charge of this case, Khadija, and I refuse to undertake the operation unless the patient is put under chloroform. If she struggled, frightful harm might be done.”

“At least I shall be here to wake her if I see that thou art taking away her soul.”

“If you do, I shall have to chloroform you too. No, if you stay in the room, you will not move unless I tell you to do anything. Otherwise I must send you away.”

Khadija was vanquished. With a grunt she wrapped her head in her veil, and sat down on the floor at the head of the bed, while Georgia and Rahah proceeded with their preparations, the carved chest in which Zeynab’s best clothes were kept serving as an impromptu operating-table. The poor little patient grew paler and paler as she caught sight of one horror after another, for she insisted on raising herself on her elbow to look at everything, and demanded that Rahah should show her the instruments one by one. Georgia put a stop to this at once, but the child’s terror was already so extreme that nothing but the determination not to allow Khadija to triumph kept her from entreating the doctor lady to postpone the operation. She looked up with a pitiful smile when the chloroform was about to be administered, and seemed almost ready to beg for a respite; but Khadija was leaning forward and scanning her face keenly, on the alert to take advantage of the slightest willingness to yield, and she said with a little gasp—

“O doctor lady, I am not frightened. Go on, O girl.”

But when the chloroform had taken effect, and Rahah moved aside a little to enable Georgia to reach the patient more easily, Khadija caught a glimpse of her charge and sprang up.

“Thou hast killed her, O doctor lady! Alas, my Rose of the World, that thy Khadija should have given thee into the hands of the infidel!” and she was about to shake the child violently, in the hope of restoring her to consciousness; but Georgia’s patience was at an end.

“Take her out,” she said sharply to Rahah, to the intense delight of the handmaiden; and before Khadija realised what was happening to her, she was outside the door, and the door was bolted on the inside, while Rahah assured her emphatically through the crack that the child was alive, and would remain so if she would only keep quiet, but that if she made any noise or disturbance the worst results might confidently be expected to ensue. Terrified by the realisation of the fact that her darling was now absolutely in the power of the strangers, Khadija crouched silently at the door and made no sign, while in the respite afforded by her exclusion from the room, Georgia, with Rahah’s assistance, performed her task speedily and successfully. The splinter was extracted and the broken bone set, after which the wound was carefully dressed, with the aid of appliances such as had never been seen in Ethiopia before, and Rahah contemplated the result with pride.

“Regular hospital treatment!” she said, adopting the words she had once heard Dr Headlam use to Georgia with reference to a case of his own, and then turned her attention to making as comfortable a bed as possible out of the coverlets and cushions scattered about, that the patient might not return to consciousness on the wretched bedstead she had occupied hitherto. When everything was finished the door was opened and Khadija again admitted. She came in suspiciously, and looked askance at all she saw; but, on finding that Zeynab was sleeping quietly, sat down beside her without uttering a word.

The operation once successfully completed, Georgia and Rahah settled down to an extremely monotonous mode of life for several days. Their sole interest and excitement was caused by the improvement or relapses of the patient, and by the necessity of keeping an eye on Khadija. Not only was it extremely likely that the old woman would try to poison them, but she also cherished a lively distrust of Georgia’s dressings, and there was a constant risk that in a frenzy of rage she might tear them off, and even interfere with the wound itself, in which case poor Zeynab would have been worse off than before. But as the days passed on and Zeynab continued to make progress, the old woman began to believe once more in the possibility of her charge’s regaining perfect health. The little face which had been so pinched and pain-lined began to recover its bloom, and Georgia found it possible to believe in the loveliness the report of which had spread even to Kubbet-ul-Haj, and which had earned for Zeynab her pet-name of Rose of the World. Warm water and the gift of a piece of the doctor lady’s soap were powerful inducements to the child to keep her face clean, and the consequent improvement in her appearance surprised no one more than Khadija. Her wild outbreaks of wrath ceased gradually as Zeynab’s eyes grew brighter and her cheeks less thin, and her manner to Georgia became markedly gracious. But this did not lead to any slackening of the precautions observed by the visitors, for they knew that their danger was considerably increased by the fact that they had performed their part of the bargain, whereas Khadija had not as yet discharged hers. Every day Rahah cooked their food over a spirit-lamp and drew from the well the water they needed, while Ibrahim also was provided for out of the stores they had brought with them. For the hours of darkness, moreover, Rahah patented a scheme of defence of which the idea was entirely her own. Before leaving Bir-ul-Malik, she had begged from Ismail Bakhsh a box of tin-tacks, and every night she strewed these upon the floor, with the points upwards. Georgia remarked that if the house should catch fire, and Rahah and she found it necessary to escape hurriedly, they themselves would be the first to suffer; but Rahah was not deterred from adopting her plan by this consideration. She had also possessed herself of a whistle, with which it was her intention to summon Ibrahim from his slumbers to the rescue, in case of an attack in force; and she explained this to him very clearly, only to discover that the idea of entering the harem, even on an errand of such urgency, appalled him almost more than the prospect that murder would be done if he stayed outside.

“But I have found out something else from Ibrahim, O my lady,” said Rahah, when describing the result of the interview to her mistress. “I know why it is that Khadija hates the name of Sinjāj Kīlin, your father. He it was who attacked her village, and whose soldiers killed her husband and son, and she has been thirsting for vengeance ever since. That is why I think we are not safe here for a moment, for in revenging herself upon you she would obtain her heart’s desire.”

But Georgia turned a deaf ear to the suggestion that she should leave her patient before her recovery was assured, although it was repeated in Fitz’s first heliographic message on the morning after her arrival. He appeared to be in a conversational mood.

“Stratford was like a dozen wild cats last night when he found you were not coming back just yet. He is afraid North will skin him alive when he turns up again. Lady Haigh is awfully unhappy about you. She says she is certain you are in great danger, and begs you to come back at once, and not to mind about the medicine.”

In answer to this, Georgia flashed back by slow degrees:

“We are quite well and safe. Operation successfully performed, but I must stay here a few days to look after patient.”

To this determination she continued to adhere firmly, notwithstanding the agonised entreaties to return which Fitz transmitted to her every day from Lady Haigh. He kept her informed of Sir Dugald’s condition, and she directed any slight changes of treatment she thought advisable, but consent to come back without the antidote she would not, in spite of the alarms of her present position. For the knowledge of these she was in large measure indebted to Ibrahim, who, for a professed fatalist, took an extraordinary delight in prophesying evil, and communicated all his anticipations of danger most faithfully to Rahah. Consequently, when Rahah came running back in much excitement one evening, after taking Ibrahim his supper, her mistress was not affected by her news to the extent she had expected.

“O my lady, Ibrahim says he is sure some evil is going to happen. Several messengers have come in during the day, bringing news to Khadija, and he is certain that one of them was from Kubbet-ul-Haj. And Khadija has been going round among the men here, stirring them up against the English, and they have all got out their weapons, and they are cleaning their muskets and sharpening their swords. Ibrahim knows that they must be going to kill us to-morrow—at least he says so; but I bade him tell the men of the vengeance the English would take on them if any ill befell us, and of the great power and hunger for war of the Major Sahib, and how he was going to marry you. I said it very loud, so that Khadija might hear, for she was not far off, but she only laughed.”

“She was probably amused by your suspicions of her,” said Georgia, absently. The fact that she had been able this evening to alter the dressings on Zeynab’s foot, and allow the wound to close, was much more interesting to her at the moment than Ibrahim’s suspicions. If all continued to go on as well as it had done hitherto, she ought to be able to return in triumph to Bir-ul-Malik in a day or two with the all-important antidote.

Rahah shook her head over her mistress’s lack of interest in her great news, and watched jealously for an opportunity of proving that her own excitement had been justified. She found one the very next day, and immediately rushed into Georgia’s room once more with her veil flying behind her.

“O my lady, there is really something wrong! Ibrahim is gone—at least, I cannot find him—and when I asked the men where he was, they only laughed at me and reviled me. And there are watchmen upon the towers, making signs to one another, and all the men and boys are gathered together with their weapons in their hands, and the women and children are sharpening knives and talking of plunder. What shall we do?”

“We can’t do anything, except keep quiet and show no fear,” said Georgia. “I don’t think they would have needed so much stirring up to attack two women, Rahah. No doubt they are not thinking of us at all. Very likely they know that some of the wild tribes intend to attack the place, and they are preparing to defend it. Perhaps Ibrahim is helping them down at the gate. Whatever you do, don’t look frightened.”

“Frightened!” said Rahah, with high scorn, and sat down in the corner to polish Georgia’s instruments. A little later Khadija entered, and asked Rahah to go and sit beside Zeynab and amuse her, since she seemed restless, and she herself was anxious to take the doctor lady into the garden and point out to her some of its beauties. Rahah looked appealingly at her mistress, entreating her mutely not to accept the invitation, but Georgia was firm in the principles she had just enunciated. Any show of fear or suspicion would only serve to irritate Khadija and put her on her guard; and moreover, if her purposes were evil, she could carry them into execution as well in the house as out of doors. Her decision seemed to be justified by the old woman’s behaviour, for she hobbled along beside her, talking as pleasantly as an ingrained habit of snappishness would permit her, and appeared anxious to exhibit the different nooks and arbours which formed the chief attraction of the garden. Georgia could not understand nearly all she said, but an emphatic word now and then, eked out by signs, gave her some idea when admiration was expected of her, and the walk was marred by no difference of opinion.

Passing through the garden, they came at last to one of the watch-towers of which Rahah had spoken, perched upon the crest of the hill, and overlooking the great gateway and the paved court, containing the famous well and surrounded by stables and other outbuildings, into which the gate opened. Khadija proposed that they should ascend the tower and look at the view, and Georgia acquiesced at once in the suggestion. To her surprise, the summit was occupied by several men armed to the teeth, in addition to the watchman; but these made way without a word for the two women, and they stood looking out on the desert. The view thus obtained was a very wide one, and Georgia noticed at once a distant cloud of dust, which appeared to be nearing the place. Khadija’s eyes were also fixed upon this cloud, and Georgia concluded that it must denote the approach of the invading band against whom the warlike preparations were being made.

For some time those on the top of the tower stood watching the dust-cloud without uttering a word. As it came nearer, there were occasional glimpses of moving men and animals and the momentary flash of steel, and Georgia felt that the men behind her were pressing closer and fairly panting with excitement.

“O doctor lady,” said Khadija, “thou seest these horsemen. Knowest thou who they are?”

“They ride in order. No doubt they are soldiers.”

“Is that all? Look again, O doctor lady.”

“Look again, O doctor lady.”

“They wear turbans—some of them, at least. They have lances with pennons. They seem to be in uniform. It is dark, like the uniform of the Khemistan Horse. They are the Khemistan Horse!”

“Look again, O doctor lady!”

Georgia looked. The cloud of dust had become much less opaque as it approached, and the forms of the mounted men could be clearly discerned. There were two or three officers among them, and Georgia’s gaze was riveted on the foremost. From the moment in which she had obtained her first glimpse of him through the flying dust, it had seemed to her that there was something familiar in his appearance; and now, as she bent over the parapet and shaded her eyes with her hand, she knew that she had not been mistaken. It was Dick, leaning forward on his horse, as though from utter weariness, and looking neither to right nor left as he rode.

“Thou seest now, O doctor lady?” asked Khadija.

“Yes, I see; but what of that?”

“Only this—and this.” Khadija’s bony finger pointed first to a spot some distance in advance of the little British column, where the track wound through rocky ground, with sand-cliffs of some height rising on either side—the dry bed of a winter torrent, probably—then to the force as it marched. “All the men of Bir-ul-Malikat in ambush there, O doctor lady, and here the English riding into the ambuscade without knowing of it.”

“But why have you brought me here?” asked Georgia.

Khadija understood the tone of the question, though not its words.

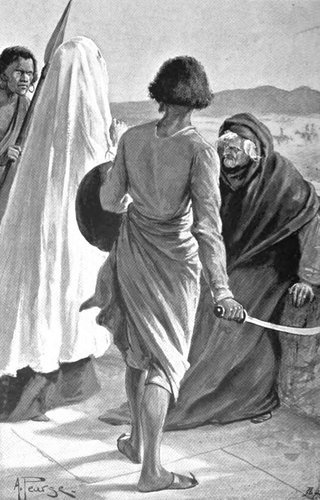

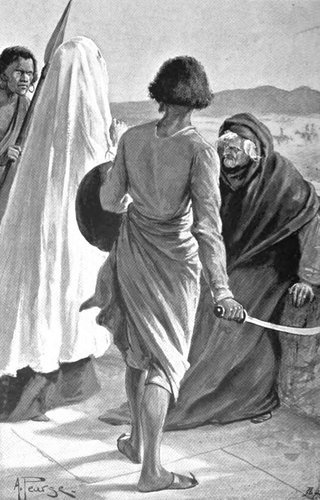

“To see what happens, O doctor lady. Not to warn thy friends—oh no! One cry—one sign of warning—and thou diest. Thou seest these men here. Their daggers are ready, and they fear not to use them.”

Georgia stood looking over the parapet, with both hands gripping its rough edge. The situation was quite clear to her without the aid of Khadija’s words, which she understood only partially, and there was no doubt in her mind as to the course to be taken. Behind were the daggers of the fanatics, who were Khadija’s willing tools—in front, Dick and his comrades, riding unconscious to their doom. Of course she would warn them. They were almost abreast of the tower now, as she stood with beating heart making her hurried calculation. The warning must necess