CHAPTER XXIII.

HARDLY WON.

Unfortunately, the Major Sahib, not knowing all the circumstances of the case, did not look at things quite in the same light as Rahah, and Georgia was not left long in doubt as to his view of the matter. Betaking herself to the terrace outside her room at the hour when she usually carried on her heliographic communications with Fitz, she was surprised to find that the conversation was opened by a complicated series of flashes in such rapid succession that she could not read them off.

“It can’t be Mr Anstruther,” she said to herself; “he never begins in that way. Can it be Dick who is doing it? It looks like some kind of private signal—or it might be ‘Attention!’ flashed very fast. Oh, here is the message!”

But the perplexity on her face only became deeper when she had written down the words, for their tone was not of the pleasantest.

“Get your things ready at once. I am coming to fetch you.

DICK.”

Was the victory to be snatched away when it was so nearly within her grasp? Georgia set her teeth hard as she flashed back—

“Cannot possibly leave to-night. Come for me in the morning.

GEORGIA.”

The answer arrived quickly.

“I am starting immediately, and shall expect to find you ready.”

This was a little too much. Georgia’s calmness, which had been subjected to a considerable strain already by the excitements of the day, gave way altogether, and it was with a hand that trembled a good deal that she signalled back—

“I must beg of you not to come, as I decline to start to-night.” Then, repenting of the tone of her message, she added, “I am longing to see you, but it is absolutely impossible for me to come before to-morrow morning.”

This time no answer was returned; but after a while, during which she stood watching anxiously, and wondering whether Dick was actually on his way to fetch her, she saw a solitary flash. This was the sign that Fitz was beginning operations, and she signalled at once—

“What is Major North doing?”

“Gone to his quarters,” came the answer, “in a vile temper. Excuse me, but this is true. Looks seedy, too; but he brought a surgeon with his force, so don’t worry about him.”

“Please tell him from me——” began Georgia, but the flashes came again—

“He won’t let me in. Stratford is calling me. I must go.”

Georgia left the heliograph with a sigh, for it was growing too late to catch the sunlight properly, and she had a hard piece of work before her this evening, the very crown and object, indeed, of her visit to Bir-ul-Malikat. Returning to Zeynab’s room, she found Khadija sitting crouched in her usual attitude upon the divan, and addressed her—

“I have performed what I promised, Khadija. Zeynab’s foot is getting on most satisfactorily, and needs only proper treatment and careful dressing, so that it is quite safe for me to return to Bir-ul-Malik to-morrow. I have shown the slave-girl, Bilkis, how to dress the wound, and I will send her over a good supply of lint and bandages and the other things I use, so that she may continue the treatment. She can do the work as well as I can, if she has the right materials. Now I am come to claim my reward. Give it to me, and let us go in peace.”

“What was it that I promised thee?” asked Khadija slowly, when Rahah had translated her mistress’s words.

“The antidote for the poison which they call the Father of sleep, and the directions for applying it,” said Georgia, promptly.

“Ah, the antidote!—it is well; I have it here,” and Khadija drew a small square box from one corner of her ample veil, which was tied up in a knot. “Take it, O doctor lady, and may it succeed in thy hands!”

“Is this all that is necessary?” asked Georgia, opening the box, and finding in it only a small quantity of flaky white powder.

“I swear to thee that it is all thou canst need.”

“And how is it to be applied?”

“Nay; I made no promise to tell thee that.” Khadija’s sharp little eyes gleamed cunningly.

“Very well, Khadija; then I shall remain here, and Yakub at Bir-ul-Malik, and my friends there will send a message to Fath-ud-Din at Kubbet-ul-Haj.”

“Nay; I was but joking, O doctor lady. Thou shalt do as I bid thee,” and Georgia noted down the details of what sounded like a rude Turkish bath, repeated three or four times, and varied by the administration of copious draughts of a decoction made with the powder in the box.

“And you are sure that you have given me all that is necessary for effecting a cure?” asked Georgia, suspiciously, for the powder possessed no healing qualities that were perceptible either to sight, smell, or taste.

“O doctor lady, I have given thee all. I swear it to thee by——” and Khadija ran glibly through a catalogue of sacred persons and objects, followed by an even more solemn list of divine names. Still Georgia was not satisfied. She looked helplessly at Rahah, for she could not hit upon any means of convicting Khadija of her falsehood, if falsehood there was. But Rahah was equal to the occasion.

“I will make her tell the truth, O my lady. Lay thy hand on the head of the child Zeynab, O Khadija, and swear as I shall bid thee.”

“O doctor lady! O my nurse! let it not be on my head!” expostulated Zeynab in a terrified voice, as Khadija rose reluctantly from her seat to comply with the imperious demand.

“Dear child, it can’t hurt you,” said Georgia. “It is merely a form.”

“Nay,” said Rahah, “rather is it that if any evil befalls thee, it is through Khadija’s lies, and by her fault. Go to the other side of the room, O my lady. Stoop down, O Khadija; lay thy hand here, and say after me, ‘If I have told lies to the doctor lady, and have not given her all that I promised, and if the Envoy cannot be cured by the medicine she holds in her hand, then let a curse light upon this child. May she wither away in her youth, and not live to see her marriage night. May the disgrace of her father ever continue and increase, and his name be blotted out without a son to bear it after him. May the house that should have mated with princes fall and perish in dishonour, and may all that remain of it live only to shame it.’”

“O my nurse, let not the curse light upon me!” sobbed Zeynab.

“Be quiet, O daughter of iniquity!” said Khadija angrily, and laying her hand on the child’s head with a menacing pressure, she repeated the words after Rahah. Zeynab made no further protest, but lay silent, looking white and frightened, much to the alarm of Georgia. She regretted deeply that she had allowed Rahah to make so solemn an attempt to work upon the superstitious fears of the old woman, and urged her to withdraw the curse, lest the thought of it should do Zeynab harm, but Rahah refused stoutly.

“I cannot withdraw it, O my lady. Khadija has invoked it, and if she was trying to deceive thee, she knew the danger that she was bringing upon the child. If she has dealt with us honestly, all will yet be well; but if evil befalls her master’s house, we shall know that it was her own doing.”

“You are certainly not so well to-night, Zeynab,” said Georgia, laying her hand on the child’s forehead as she prepared to leave her at bedtime. “Is anything the matter? Surely you are not thinking of those foolish words? I am very sorry that I let Rahah say them, but they can’t do you any harm.”

The child made no answer, but looked up with a frightened face, and Rahah translated Georgia’s first remark for the benefit of Khadija. The old woman sprang up from the divan instantly, in a towering rage, and after a hasty glance at Zeynab, turned upon Georgia and Rahah, and drove them out of the room with a storm of curses, alleging that they had bewitched the child in order to frighten her. When they reached their own room, Georgia was inclined to be low-spirited over the issue of her mission, but her maid displayed no signs of discouragement.

“Wait!” she said mysteriously, and they waited, taking the opportunity of gathering their possessions together in view of the return to Bir-ul-Malik the next day. They had been in their room about an hour, when the jingling of anklets along the passage, and a hurried knock at the door, announced a visitor. Rahah opened the door cautiously, and Khadija entered and walked up to Georgia.

“Give me the medicine,” she said abruptly, and taking from her bosom a small phial, half filled with a clear colourless liquid, she emptied the powder into it from the box, shook up the resultant mixture, and closing the phial, handed it back to Georgia.

“Take it, O doctor lady,” she said. “But for the curse, thou shouldst never have had it. But truly God is great, and He is good to the accursed English, so that the old spells and the magic of our fathers cannot stand before theirs. And now come and take away the curse from my Rose of the World, for I cannot see her fade and die before my eyes.”

Followed by Rahah, Georgia returned to Zeynab’s room, where they found the child tossing restlessly on her bed.

“O my nurse, take it away!” was her cry. “I feel the curse; I know it has come upon me. I cannot sleep. There is a weight on my heart and a fire in my bones, and it is thou that art killing me.”

“The curse is gone, my dove,” said Khadija. “I have given the rest of the medicine to the doctor lady.”

“But how can I believe thee? I feel no better,” moaned Zeynab.

“O doctor lady, wilt thou still kill my child?” cried the old woman in a frenzy. “I could give thee no more if she were dying at this moment. Take away from her thy curse and thy evil enchantments.”

Sitting down beside the bed, Georgia took the hot little hands into one of hers, and with the other smoothed back the tangled hair from the child’s brow. It was more than an hour before all her stories and her talk could banish the haunting horror from Zeynab’s mind, and induce her to close her bright eyes, and her doctor was nearly worn out when she was at last able to leave her. Sheer fatigue made Georgia sleep soundly, in spite of the excitement of the past day, and she and Rahah were not disturbed again that night. In the morning Fitz flashed an inquiry as to the time at which she would like to be fetched from Bir-ul-Malikat, and about eleven o’clock she saw the cavalcade she was expecting enter the courtyard. There was a hurried collecting together of packages, a hasty farewell to Zeynab, who wept copiously, and would not be comforted even by the promise that she should receive every picture-paper Georgia could lay her hands on, and then, accompanied by Khadija, the visitors went down to the courtyard. To Georgia’s surprise and disappointment, it was Stratford and Fitz who came eagerly to meet her as she appeared at the door shrouded in her burka.

“Where is Dick? He is not ill, is he?” she asked anxiously of Stratford, remembering Fitz’s message of the night before.

“He is so busy that he was obliged to send his apologies, and allow us the honour of escorting you instead of coming to fetch you himself,” said Stratford, in tones which were absolutely devoid of any suggestion of ulterior meaning.

“Oh!” said Georgia, blankly.

“He found himself compelled to hold a full-dress review of his detachment, or inspect their kits, or do stables, or something complicated and professional of that kind,” said Fitz, with a dogged resentment aggressively conspicuous in his manner.

“Nonsense, Anstruther! You know as well as I do that he would have allowed nothing but absolute necessity to keep him from coming,” said Stratford.

“Oh yes, of course,” said Georgia, in the most natural tone she could command. She would not let it be seen that she perceived the flimsy character of the excuse, but she felt deeply mortified as she allowed Stratford to mount her on her horse, and she resented his evident determination to smooth things over almost more than Fitz’s undisguised incredulity. “How horrid of Dick!” was what she said to herself as she gathered up the reins, and the hot tears rose to her eyes under the shadow of the burka.

“Stay, Englishman!” cried Khadija from the doorstep, when Stratford, having seen Rahah and the luggage safely bestowed, was about to mount his own horse. “Where is Yakub, my son, whom I left at Bir-ul-Malik as a pledge for the safe return of the doctor lady?”

“I hope that Yakub will come back to you safe and sound in a few days,” returned Stratford in Ethiopian, speaking so carefully that it was evident he had studied his sentences with Kustendjian before starting. “For the present, however, I think it well to detain him, on my own responsibility. We don’t want any mistakes made about that medicine for the Envoy. As soon as he has recovered, you shall have your son back.”

For answer, Khadija threw herself upon the ground, wailing and tearing her hair and beating her breast, and calling upon Heaven and upon Georgia to witness that she had performed all that was required of her, and that she had given her all the necessary ingredients for the medicine. Georgia, remembering the scene in Zeynab’s room the night before, and indignant at being compelled to bear a part in what was not far removed from a breach of faith, espoused her cause, and joined her in demanding that Yakub should be at once released. In spite, however, of all that she could say, Stratford remained immovable, and mounting his horse, ordered an immediate start. But before the horses had gone more than a few steps, Khadija rose from the ground, and forcing her way through the escort, caught hold of Georgia’s rein.

“O doctor lady,” she cried, with such reluctance that she seemed almost to be torn in two by the conflicting passions in her mind, “I had forgotten one thing. After the first administration of the medicine, the sick man will sleep for two days and two nights a natural sleep. If he is awakened in that time he will die, but if he awakes of himself, all will be well. And now”—her tone changed suddenly—“now go thy way, O thrice accursed daughter of an accursed father, and when first thy bridegroom looks upon thy face on thy wedding-night, may he turn his back on thee and say, ‘O woman, I divorce thee!’ and so thrust thee out.”

“Come, that’s enough,” said Stratford peremptorily, loosening her hand from the rein. “You know now that it depends on yourself whether your son returns to you in safety or not. Has Anstruther told you, Miss Keeling, that we had a messenger from Jahan Beg the day before yesterday?”

“No, I had not heard of it,” returned Georgia, following his example in ignoring the baffled Khadija, who stood shaking her fist and shrieking curses after the party. “What news did he bring?”

“The best news possible. Jahan Beg has succeeded in unearthing the conspirators who were troubling him when we left the city, and has made it impossible for them, at any rate, to do more plotting. Among other things, he discovered that they meant to stop us and keep us here in order to get hold of the treaty, and therefore he sent stringent orders to Abd-ur-Rahim to let us go at once with all our property, on pain of death. Messengers were also sent to all the towns and forts on the road and along the frontier, ordering the governors on no account to oppose the advance of any English relieving force coming from Khemistan, but to afford it every assistance, as if they didn’t Fath-ud-Din would suffer. That accounts for North’s getting back to us so quickly.”

“How far had he to go?” asked Georgia.

“Only as far as Rahmat-Ullah, for Hicks had got there before him, and frightened the Government about us a good deal, so that they had already ordered up a couple of troops of the Khemistan Horse, in addition to those usually stationed at the fort, and as soon as they arrived he started back with them. Of course such a small force would have been no use if the country had been up, but it was intended merely as an armed escort, just to make a dash for Bir-ul-Malik and back to Rahmat-Ullah.”

“Then they must have travelled very fast,” said Georgia, her mind reverting to her glimpse of Dick the day before.

“Yes, they made forced marches all the way. North kept them at it, but he looks awfully done up now,” said the wily Stratford.

“It would have done him good to ride out here,” said Georgia, refusing to commit herself.

“Yes; but you know how conscientious he is. So long as there is anything to be done, he will simply work till he drops.”

“Oh dear, I do hope he isn’t going to be ill!” sighed Georgia, and Stratford judged that his scheme had succeeded. He guessed rightly, for all the resentment in Georgia’s mind was swallowed up in anxiety, and she could not spare a thought for her own insulted dignity when Dick was suffering, perhaps had even endangered his life, through his eagerness to rescue her. She said little during the remainder of the ride, and could scarcely devote a moment even to glancing at the camp of the Khemistan Horse, which was pitched beside the hill of Bir-ul-Malik. Arrived at the palace, she bestowed a hasty greeting on Kustendjian and Ismail Bakhsh, and hurried into the harem in search of Lady Haigh, who rushed to meet her, and in the intervals of kissing and crying over her, scolded her soundly for her persistence in remaining away.

“But I have got the antidote!” cried Georgia, exhibiting the little bottle proudly; “and remember, Lady Haigh, you promised that I should use it.”

“How could I prevent your trying it, my dear child, when you risked your life in obtaining it? But it was not even your danger that I was thinking about so much at the moment. It was Major North, and his view of the case.”

“Oh, Dick and I must settle our little differences together,” said Georgia, as lightly as she could. “Where is he? I haven’t seen him yet.”

“I think I hear his step outside,” said Lady Haigh. “He must have followed you into the house. But, Georgia, I must warn you, he looks very seedy, and I think he is just a little bit cross. Don’t be harder on him than you can help, dear, for he has been through a fearfully anxious time. He has had very little sleep since he left here, and has been at work day and night, almost without a rest.”

If Lady Haigh considered it advisable to offer her this warning, Georgia judged that Dick’s fit of ill-temper must be of an extremely pronounced character; but her conscience was clear, although her heart beat a little faster than usual as she left Lady Haigh in the inner room and went out into the larger one. Dick was leaning against the framework of the lattice, and raised himself slowly to greet her.

“Oh, Dick, how ill you look!” she cried. “My dear boy, you ought to be in bed.”

As soon as the words had passed her lips, she was struck by their singularly malapropos character under the circumstances, and Dick frowned heavily.

“Well, Georgia?” was all he said.

“Why, Dick, have you nothing more to say to me than that? Do you know that you haven’t seen me for over a week?”

“I was under the impression that you might have seen me yesterday evening, and preferred not to do so.”

“But I couldn’t help that. It was not a matter of choice. One can’t leave a patient before his cure is fairly complete.”

“You prefer your patient to me, then?”

“To see you would have been a pleasure; to stay there was a duty.”

“Even when I had desired you to come back at once?”

“That couldn’t alter my duty.”

“Indeed?” Dick lifted his eyebrows. “Then my wishes have no weight with you whatever?”

“They have great weight with me, but mine ought to have just as much with you.”

“This is rather a new theory,” said Dick, with elaborate politeness. “Is its application intended to be permanent, or only temporary?”

“I see no reason to anticipate any change that would render it out of date.”

“Thank you. That’s pretty clear, at any rate. Perhaps you will kindly explain to me your views of the marriage relation? So far as I can see, they involve two heads of one house.”

“I don’t want to discuss the question now, especially since we used to argue it so often in the old days,” said Georgia; “but if you insist upon it, I will. I know very well that there can be only one head, practically speaking, to a household—that when two people ride one horse, one must ride behind—and because I love you and trust you, I am quite willing to take the second place. But I do expect to be consulted as to the way the horse is to go. You could never have imagined that I would allow myself to be carried off anywhere blindfold. I think that we should discuss everything together and agree upon our course, and if at any time circumstances should prevent our discussing some special plan, I expect you to trust me if I find it necessary to act on my own responsibility, just as I should be ready to trust you in a like case.”

“This is the New Woman’s idea of marriage!” sneered Dick.

“It is my view of it, at any rate. Did you expect to find in me a slave without any will of her own, Dick? I am not a young girl, but a woman, who has led a sufficiently lonely and independent life, and you knew that when you asked me to marry you.”

“Yes, and I was a fool to do it,” said Dick, roughly.

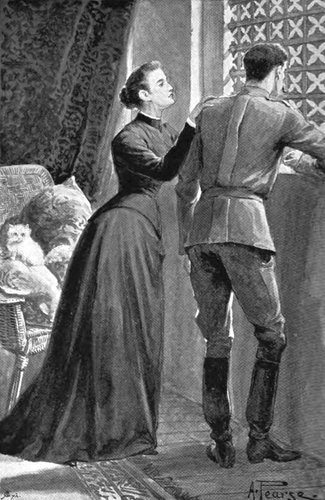

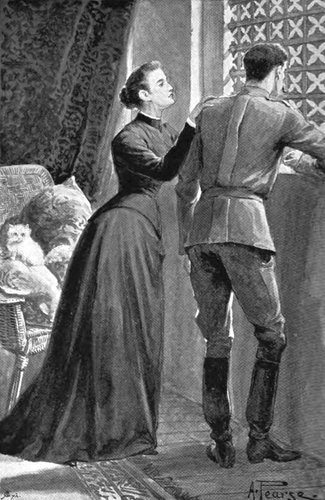

Georgia turned away, deeply wounded, and he stood at the lattice, looking out over the desert with gloomy eyes. She did not know that more had happened to try his temper than even the hardships and anxiety of which Lady Haigh had spoken. An ill-advised comrade, who had heard of his engagement through Mr Hicks, had seen fit to chaff him that morning on the eagerness with which he had pressed forward to rescue a lady who neither wanted his help nor desired his presence, and the words had rankled in his mind. But although Georgia was ignorant of this fact, she could not consent to leave things in their present state. To take offence at his hasty speech, and break off her engagement there and then, would be a course of conduct worthy only of a mythical lady who always acted the part of an awful warning for Georgia and her friends, and whom they were in the habit of calling “The Early Victorian Female.” It is, perhaps, needless to add that this person was given to gushing over indifferent poetry, fainted with great regularity at the most inconvenient moments, and when she had a misunderstanding with her lover, accepted the fact meekly, and pined away and died. Georgia felt it morally impossible to imitate her. To what purpose had been her own education and her experience of life if they did not enable her to stoop to conquer, and to hold her own without being aggressive? Was all that had passed between herself and Dick to be blotted out by a few words spoken in a moment of irritation? She crossed the room to his side and put her hands on his shoulders.

She crossed the room to his side and put her hands on his shoulders.

“Look at me, Dick,” she said. But Dick would not turn round.

“You goad a man into saying beastly things to you,” he muttered, “and then you try and get round him when he is feeling ashamed of himself.”

Such an unpromising reception of her effort to make peace might well have daunted Georgia, but she could forgive much to Dick, simply because he was Dick. She turned his moody face towards hers and made him look at her.

“Don’t think of it any more, Dick,” she said. “My dear boy, do you imagine I don’t care for you enough to forgive you that? And let us leave the question of our married life to right itself. If it hadn’t been for this, we should have glided into it naturally, and things would have settled themselves. Surely two people who are neither of them by nature quarrelsome, and who are anxious to do right, ought to be able to get on together, if both are willing to give and take? I can trust you, Dick; won’t you trust me?”

It added considerably to the discomfort of Dick’s present state of mind that he was conscious that Georgia was behaving with a magnanimity to which he could lay no claim, but he had started with the determination to put his foot down, and to show Georgia before they were married that he would stand no nonsense, and he stuck to his point doggedly. “I don’t intend to be made to look a fool before all the world,” he growled.

“But who would want to make you look a fool? You must know that your honour is as dear to me as to yourself. Haven’t I shown that I won’t keep you back when duty calls you? Can’t you trust me, Dick? If you can’t, things had better be over between us, indeed. Suppose you were out, and I was summoned to a dangerous case, and couldn’t possibly let you know. It would be my duty to go, just as it would be yours to start if you were ordered somewhere on special service, and couldn’t even say good-bye to me. Can’t we act on this understanding?”

“But how can you be sure that you can trust me, may I ask? Many men make rash promises before marriage, and break them like a shot afterwards. How do you know that I am not one of them?”

“Oh, not you, Dick! You are a gentleman; I can trust you fully. Tell me that you will agree, and let us forget all this worry.”

“You are trying to get round me,” said Dick again, helplessly. “I can’t think what I was going to say; everything seems to have gone out of my head. What is the matter?” looking irritably at her frightened face. “There’s nothing wrong with me. I think—things had better be—over between us, Georgie. We should never—agree. What was I saying last? What’s the matter with the walls? Is it—an earthquake?”

He was reeling as he stood, and clutching wildly at the frame of the lattice for support. Georgia caught him by the arm, for he had missed his hold and was swaying backwards and forwards, and succeeded in guiding him to the divan.

“I feel—awfully queer,” he said, and fainted away before Georgia could seek a restorative. She cried out, and Lady Haigh and Rahah came rushing in, the latter followed by Dick’s bearer, whose countenance declared plainly that he considered his master’s illness to be entirely due to Georgia, and that it was just what he had expected. With the help of some of the other servants, Dick was carried to his own room, where for several days he was to lie moaning and tossing under a bad attack of fever. Georgia had her hands full during this period, even though the bearer declined respectfully to allow her any share in the actual nursing, for besides her care for Dick, she was engaged in testing, with scarcely less anxiety, the effect upon Sir Dugald’s health of the antidote she had obtained with so much difficulty. She would have preferred to choose a time when she could give her whole attention to his case, but he had appeared so much weaker of late that Lady Haigh was feverishly eager for the remedy to be tried at once, and in fear and trembling Georgia put into practice the directions she had received from Khadija. Her courage revived to a certain extent when she found that the resulting symptoms corresponded exactly with those described by the old woman, but the two days of heavy slumber proved to be a period of intense anxiety. Every sound was hushed in the neighbourhood of Sir Dugald’s sick-room, and the watchers scarcely dared to move or breathe. At last, just as Georgia had returned to her other patient after a heart-breaking visit to Dick, who was calling on her constantly, although he refused to recognise her when she stood beside him, there was a sudden movement on the part of Sir Dugald, and Lady Haigh grasped her arm convulsively.

“Go to him, and let him see you first when he wakes,” said Georgia, in a low whisper, and Lady Haigh obeyed.

“Well, Elma!” It was Sir Dugald’s voice, very weak, but without a hint of delirium. “Haven’t you got the place rather dark?”

Georgia threw the lattice partly open, and he looked round.

“Still at Kubbet-ul-Haj, I see.” They had purposely arranged the bed and the camp-furniture in the same positions that they had occupied in his room at the Mission, with the object of avoiding a sudden shock. “I should have said we must have left it long ago, but I have had the most extraordinary dreams. Could it have been a touch of fever, do you think? But is that Miss Keeling? Ah, this explains it. I must have been ill?”

“Yes, you have frightened us all very much, Sir Dugald,” said Georgia, for Lady Haigh was incapable of speech.

“Ah, it was a bad attack, then, was it? Queer that I don’t remember feeling it coming on. The treaty is not signed yet, I suppose?”

“Yes, it is signed. You have been ill for some time—longer than you think.”

“I always knew that Stratford was a clever fellow. This is the best news you could have brought me, Miss Keeling. But we ought to be thinking of returning to Khemistan if we have secured the treaty. How long do you give me to get well enough to mount a horse again?”

“You mustn’t be in too great a hurry. We might carry you in a litter.”

“No, thank you. It would be too much like my dreams. I have suffered agonies through imagining that I was in a trance, and about to be buried alive, because they thought I was dead. It seemed to me that I could see people moving about all round me, but I could not move, or speak, or feel. Then I was put in a coffin, and carried off to be buried. It always ended there, but it came over and over again. It was the horrible helplessness—my absolute powerlessness to make any sign to show that I was alive—which was the worst thing about it.”

“Oh, Dugald!” cried Lady Haigh, in a strangled voice—and kissing him hastily, she hurried out of the room.

“Lady Haigh has been very much frightened about you, Sir Dugald,” said Georgia. “She has watched over you night and day, and I have often wondered that she did not break down.”

“Please look after her,” he said, anxiously. “She has wonderful pluck, but sometimes she is obliged to give way altogether, and I’m afrai