SIXTH WONDER

THE LIGHTHOUSE OF ALEXANDRIA

The day after their walk in Kensington Gardens, Diana, full of distress, ran in to see Rachel early in the afternoon.

“What do you think? I have to go to the seaside to-morrow!” she exclaimed, breathlessly. “Mother and Father are going, and they say I’m to go with them, and—”

“But how lovely!” interrupted Rachel. “For you, I mean. It will be horrid for me,” she added, dejectedly. “Why don’t you want to go?”

Diana stared at her. “Don’t you understand? I shall be away more than a week, and”—she lowered her voice mysteriously—“the seventh day, you know, will come round, and I shan’t be here, and I shall miss the chance of an adventure. Oh, I do envy you, Rachel! I’d rather never go to the seaside again than miss all the exciting things that might happen. And you see I can’t explain why I don’t want to go—so it’s all perfectly horrible.”

“But you know I don’t believe it makes a scrap of difference where we are,” declared Rachel. “If ‘he’ wanted us to go to the Museum, or to Egypt, or to Rhodes, or anywhere, we could go just the same, whether we were in London or by the sea, or at the North Pole. You remember what everybody says about him.” She glanced over her shoulder to make quite certain that they were alone, and went on to quote in a whisper, “‘Sheshà, greatest of Magicians.’ Salome said that, when I was in Babylon, and the other night, you remember, Bucephalus said it when he changed into a real horse. And, of course, he is the greatest of magicians. He can do anything he likes. I shouldn’t worry a bit about going away if I were you. I only wish I had the chance.”

Diana’s face became radiant.

“I never thought of that!” she exclaimed. “How clever you are, Rachel. Oh, if only you were coming, too, it would be perfectly splendid.”

Rachel sighed. “It will be awfully dull without you. But all the same I expect I shall meet you somewhere or other in a few days. Seven days, or perhaps nights, from the evening before last, you know!” she went on with a little chuckle of anticipation.

She felt nevertheless so depressed at the thought of losing Diana, even for a short time, that what happened next seemed altogether too good to be true.

“Would you like to go to the seaside with Diana?” enquired Aunt Hester at tea-time.

Rachel’s face of joy was such an answer that Aunt Hester laughed.

“Well, I think you may. I’ve just had a note from the child’s mother to say you could share a room with Diana at the hotel. They’ll be there for a week.... It will do her good to get out of London for a few days,” she went on, turning to Miss Moore. “She’s a country child, you see, and she’s beginning to look a little pale. A breath of sea air won’t hurt her.”

Rachel could have screamed for delight, and as though things could not happen too fortunately, just at that moment, Mr. Sheston was announced.

She hadn’t seen him for nearly a fortnight, so she would anyhow have been very glad of his arrival, but to-day, his coming seemed specially fortunate as a kind of sign that she had been right in offering consolation to Diana. A few minutes later, indeed, she was even more certain of it.

“It’s no use suggesting a visit to your favourite place of amusement,” said Aunt Hester, in a quizzical tone when she had welcomed the old gentleman and given him some tea. “Rachel is going to St. Mary’s Bay for a week with her little friend, so she’ll be far away from such entertainments as museums.”

“So shall I,” returned Mr. Sheston, helping himself to cake. “Curiously enough I’m going to St. Mary’s Bay in a day or two for a little change of air.”

Rachel really did scream for joy at this news, and when, after some eager questioning she discovered that Mr. Sheston was actually going to the very hotel in which Diana’s father and mother had taken rooms, she was almost sure that whatever else happened, she and Diana would not miss an “adventure.”

It was altogether delightful at St. Mary’s Bay. The weather was perfect. Diana’s father and mother were, next to her own, Rachel thought, the nicest father and mother in the world, and it was gratifying to find that they very much liked their little daughter’s new friend, Mr. Sheston. All day long, she and Rachel were out of doors, scrambling about bare-footed on the rocks, and enjoying themselves tremendously.

At intervals, of course, they discussed their chances of an adventure, and, as the magic seventh day approached, their excitement increased.

“It makes it such fun that he never says anything about the magic between whiles, doesn’t it?” Rachel observed on the morning of the day when something might be expected to happen. “He’s just like a nice old gentleman, except at ‘seven’ times. Can’t you imagine how people would stare at him if they knew he was Sheshà, and Dinocrates, and Cleon, and ever so many more?”

“And that he can make Alexander’s beautiful horse come back again to the world, and fly with us to Halicarnassus!” put in Diana with a laugh of triumph. “They only think he’s a dear, clever old gentleman who knows all about things in the British Museum. It’s jolly to be us and to know ever so much more about him than just that!”

“Don’t forget he’s promised to take us up the lighthouse this afternoon,” remarked Rachel, as they went into the hotel for lunch.

They reminded him of this promise almost before he had taken his place opposite to them at the table, and an arrangement was made to meet on the terrace outside, at three o’clock. “After I’ve had my nap,” said Mr. Sheston, in his character as an old gentleman who took care of himself and could not do without his midday sleep.

Punctually at three o’clock, however, he made his appearance on the terrace, and they all set out to walk to the lighthouse.

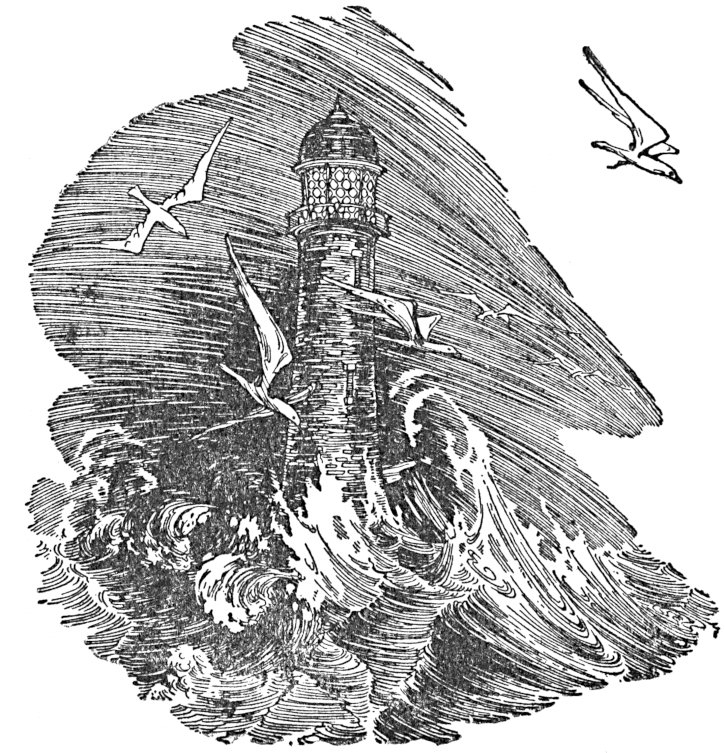

It was built at the end of a long spur of rock which jutted out from the bay for quite half a mile, and when at last they reached the strong stone tower, both children thought how lonely was the spot on which it stood.

It was great fun to climb the twisting stone staircase within the lighthouse and to come at last into the “lantern”—a round room at the top, from which there was a wonderful view of the great expanse of sea now calm and blue as any mountain lake.

“Oh, I should like to live up here!” exclaimed Diana, enthusiastically, when the lighthouse-keeper had explained all about the working of the great shining lamp.

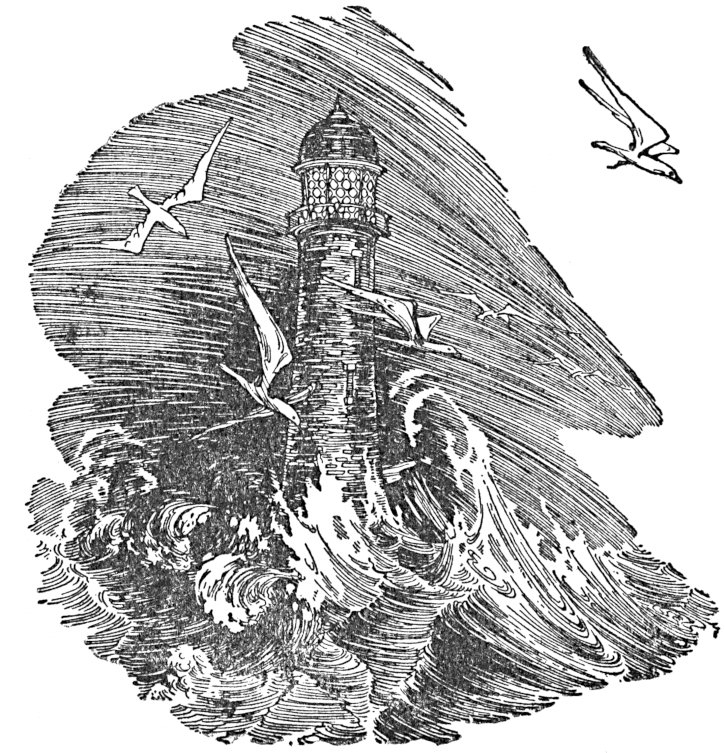

“Ah, it’s all very well now, missie,” returned the old sailor-man, shaking his head. “But you wouldn’t like it so much on some of the nights we gets up here in the winter. To look at that there sea now, you’d never think, p’raps, what it’s like in the winter when there’s a great storm, and the waves come on mountains high, a-dashing all around, with the wind howlin’ and shrieking like a lot ’er wild animals, and the spray tossin’ right up to them there winders, and beatin’ against ’em like mad. And the birds—them sea-gulls flying round the light as they do—gettin’ all ’mazed-like and confused, dashin’ theirselves against the glass, poor things, an’ cryin’ most uncanny.... It’s wild enough up ’ere then, I can tell you. Not altogether comfortable-like either,” he added, with a broad smile.

“And it’s even worse for the poor sailors in the ships, isn’t it?” said Rachel, nodding seawards. “How glad they must be to see your light that keeps them from getting on to the rocks. I should think they feel awfully glad then that lighthouses are invented. How were they invented?” she asked, suddenly turning to Mr. Sheston. “I mean who first thought of making a lighthouse?”

Scarcely had she asked the question, when the glass-encircled room, with its huge lantern, was blotted out in darkness. Another second and Rachel felt a fresh wind blowing in her face, and, before she had time to cry out to Diana, Diana herself gave a scream of amazement and delight.

“Rachel! Look—look! What is it? Where are we?” she cried.

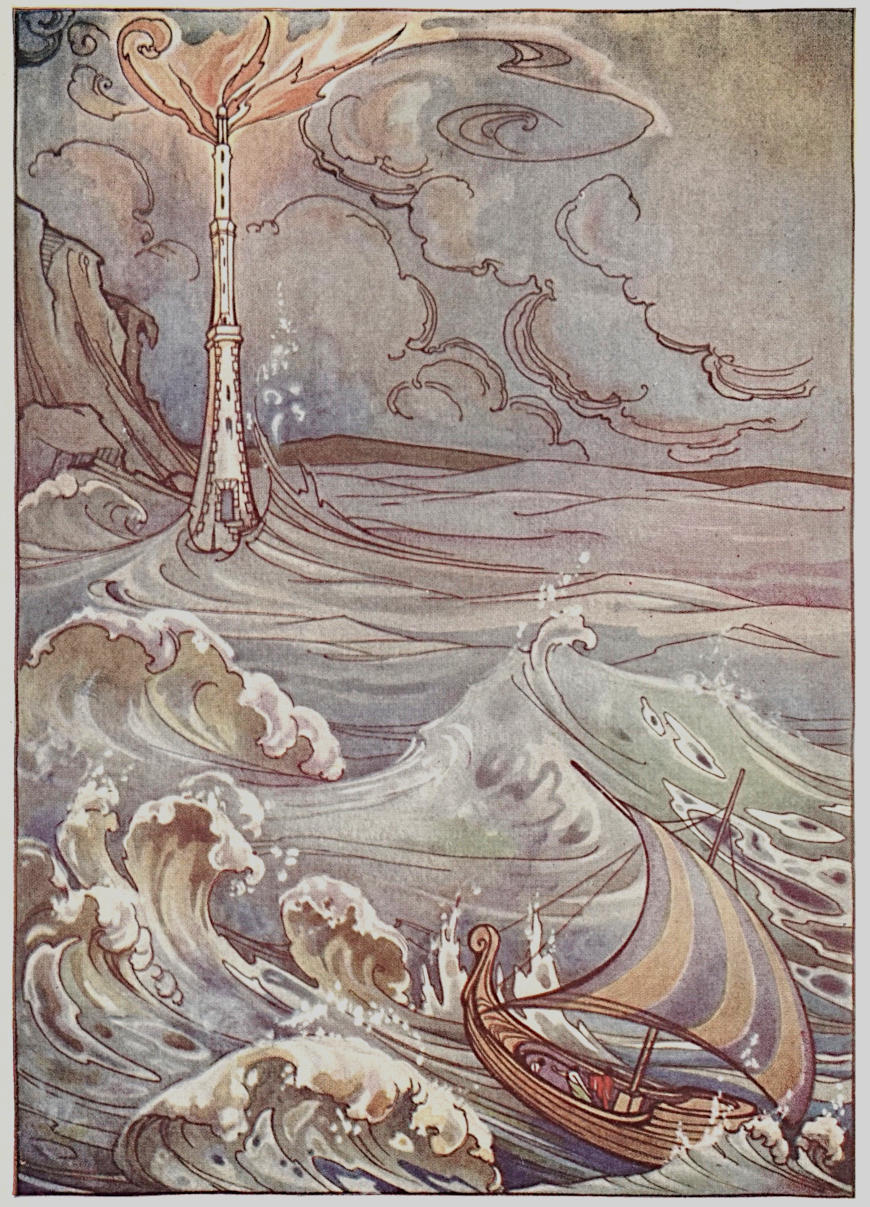

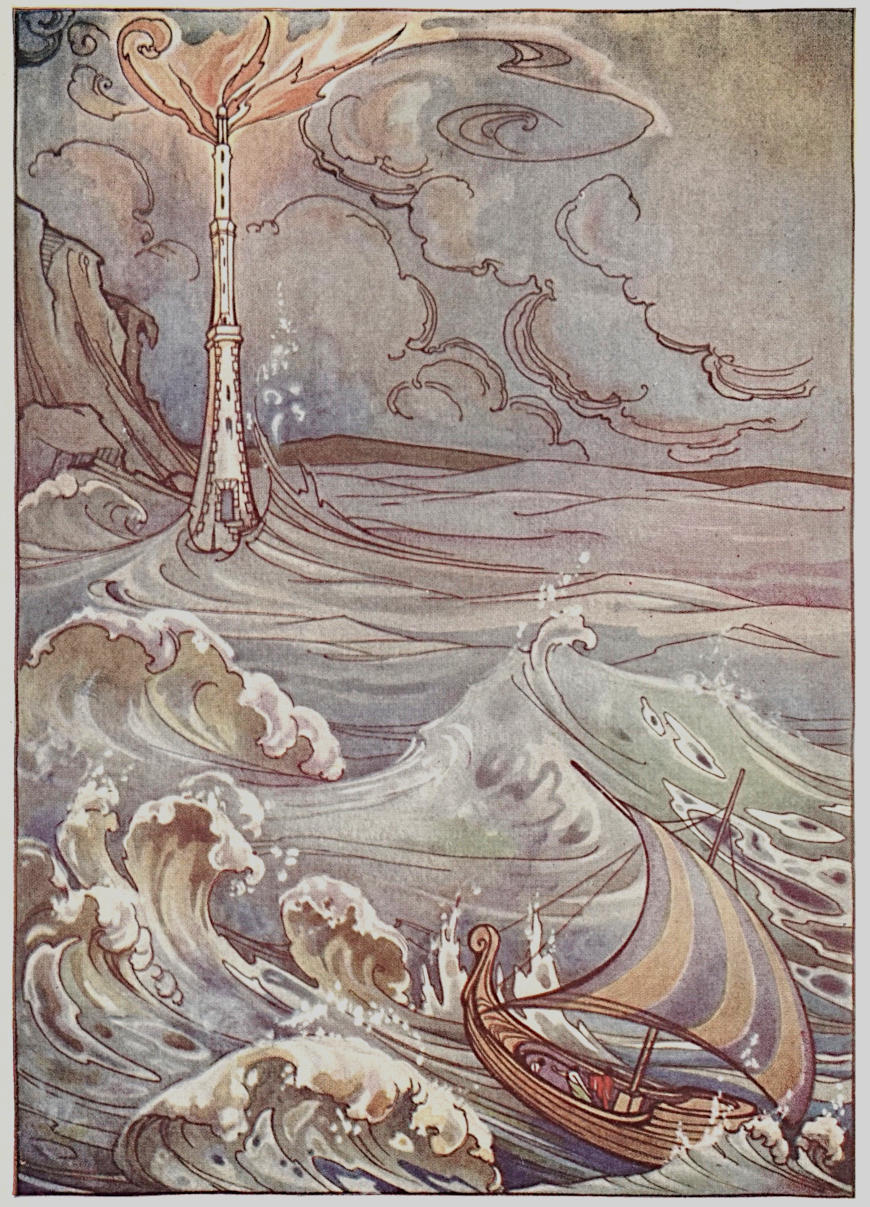

For a moment Rachel paid no heed to the second question. She had no idea where she stood. She only knew that she was gazing upon something very strange and wonderful. It was night and quite dark, and she heard the sound of water lapping close to her feet. But her eyes were fixed upon something that looked like a gigantic lily rising out of the sea, and made visible by flames, which at its summit leapt and danced and streamed upwards towards the night sky.

“We’re on a ship,” whispered Diana, excitedly.

And then, for the first time, Rachel realised that she was standing on the deck of a vessel, and that all around her, sailors were moving, busy with ropes and sails as they shouted to one another in a language she did not understand.

The flames darting from the top of the wonderful column lighted up a great track of water between the ship and the coast, which was plainly visible in the red glare of the fire. So also was the ship that sailed over the illuminated sea, and the figures of the sailors on board. They were like no sailors she had ever seen, for they were clothed in a strange fashion, and wore curiously shaped caps.

“There is the first lighthouse,” said a well-known voice, and turning together, the children saw standing behind them—Mr. Sheston. Rachel, at any rate, knew it was Mr. Sheston, even though he looked quite different, and wore a tunic with a cloak thrown over his shoulders, for she was accustomed by this time to seeing him in various guises.

“Oh, do tell us where we are,” she begged. “We’re on the sea, of course—but what sea is it? And how far are we back into the Past? And what is your name this time?”

The tall dark man laughed.

“Let me take the questions singly. This is the Mediterranean Sea. We are about two thousand five hundred years back into the Past. The land there is the coast of Egypt. And my name you already know, for I am Dinocrates.”

“Oh, then it was you who built the Temple of Diana?” asked Rachel.

“And you were the little boy with the leopard skin? And afterwards—hundreds of years afterwards—you built the first temple—and the second and third ones too,” cried Diana. “Mr. Sheston told us all about you, and——”

But here Diana paused, for she suddenly realised that Dinocrates and Mr. Sheston were one and the same.

Rachel had evidently come to a like conclusion, for all at once she said in a whisper, “I thought so.”

There was silence for a moment while both children, rather confused, were considering the strangeness of this. Then Rachel, who was never very long quiet, began again:

“There’s a great town behind the tower, isn’t there? When the flames blow backwards I can see the houses.”

“You behold the city of Alexandria.”

“Alexandria?” repeated Diana quickly. “That reminds me of—last time. Bucephalus, you know, and Alexander the Great.... Has the town anything to do with him?”

“Everything,” answered Dinocrates. “He founded it, and gave to it his own name, the name by which men who live in your world of to-day, still call it. But it was I who built it,” he added. “That is, you understand, it was I who made the plans for the building of the city.”

“And did you build the lighthouse too?” asked Diana.

Dinocrates shook his head.

“Nay, not to me, but to another, do the sailors owe that tower of warning—the tower that has saved many lives.”

“Do tell us about it,” urged Rachel. “Who first thought of it? I suppose the sort of lights we have now with reflectors and all that, weren’t invented when this lighthouse was made? But what a good idea to make flames come out at the top instead.”

“You shall hear the story of the lighthouse,” said Dinocrates, “but let us sit at our ease while I relate it.”

He pointed to a coil of ropes, and the children, settling themselves close together upon it, found that it made a most comfortable seat.

Dinocrates meanwhile wrapping his cloak about him lay full length upon the deck near them, and turned his face in the direction of the lily-white tower with its crown of leaping flames. For a moment he did not speak, and the children were so impressed by the wild beauty of the scene that they too were silent.

The vessel, as strange to their eyes as were the sailors who formed its crew, glided slowly and softly over the dark water on which lay a pathway of crimson light. To and fro moved the sailors, sometimes singing, sometimes laughing, sometimes shouting to one another as they went about their work, but paying no heed to their visitors.

The flames from the lighthouse rising and falling revealed a coastline with a fringe of white houses, and on the sea other ships moving in various directions, their sails sometimes lighted up brightly in the red glow of the fire.

Rachel, who had sunk into a sort of happy dream, started when at last their companion spoke.

“Do you remember,” he began, “what Bucephalus, that famous horse, has already told you concerning his master, Alexander the Great? How that he set out to conquer the world? Bucephalus has, I know, related to you how his master took the city of Halicarnassus in Asia Minor and visited the tomb of Mausolus, built by the sorrowing Queen Artemisia. That, however, was only the beginning of his victories.

“A little later, when all Asia Minor owned his sway, he turned his thoughts to Egypt and conquered that country also. Sailing in his barge up the great river Nile which waters the land, he came at last to where it flows out into the sea—this very sea upon which you are now sailing. But he found no city there, such as by the light of that beacon fire you now behold. Only a few poor huts stood then at the mouth of the great river. ‘Here,’ thought Alexander, ‘is the place for a mighty port, and here a mighty town shall arise. But whom shall I employ to build such a city for me? Who is the greatest architect now living?’ Instantly my name was upon his lips. For, only a year before, he had seen the great new temple I had completed at Ephesus, in honour of Diana.

“At once he sent for me, and straight from the building of that temple in Ephesus I came hither. Let me now show you, little maids, what I found where now that lighthouse and that city stand. Rise, and bow with closed eyes seven times in the direction of the shore.”

Rachel and Diana needed no second invitation. They leapt to their feet and obeyed.

THE PHAROS LIGHTHOUSE

“Open now your eyes and behold,” said Dinocrates.

Again the children did as they were told, and found, scarcely to their surprise now, so accustomed to marvels had they grown, that the night had vanished. It was broad daylight, and the sun streamed down upon a bare rocky island separated by a narrow belt of sea from the mainland. There was no city, no lighthouse, only a few rough huts upon the rocky island round which the sea-gulls circled, uttering sad cries. A mighty river, flowing through miles of flat land, poured its waters into the sea close to the island.

“This,” said Dinocrates, when the children had gazed a moment at the scene, “was what I found, when, at the command of Alexander, I came hither to build the city. That bare island in front of the mainland was then, and is still called, the Isle of Pharos.”

He waited a moment.

“Close once again your eyes, and wait till I pronounce the magic number,” he presently directed.

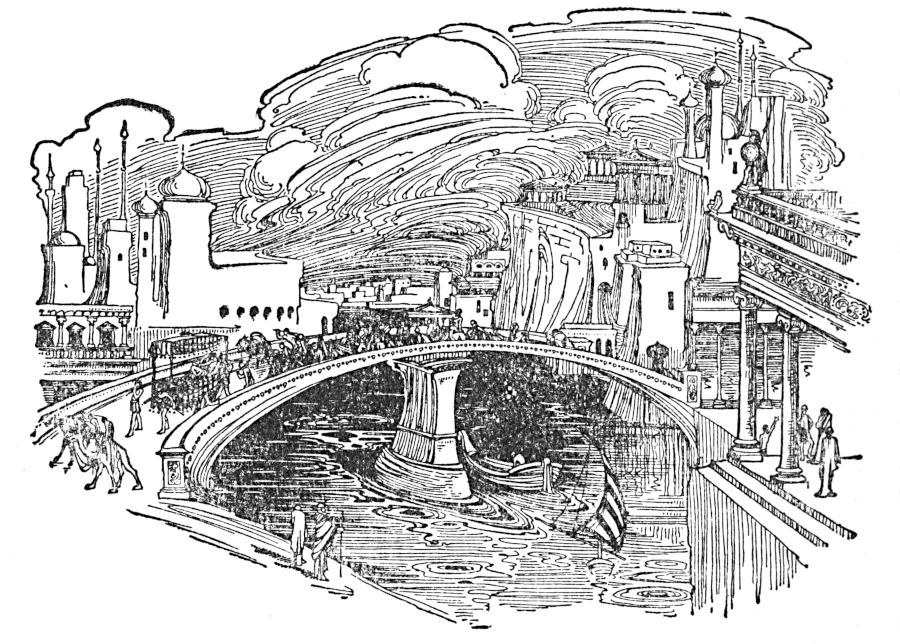

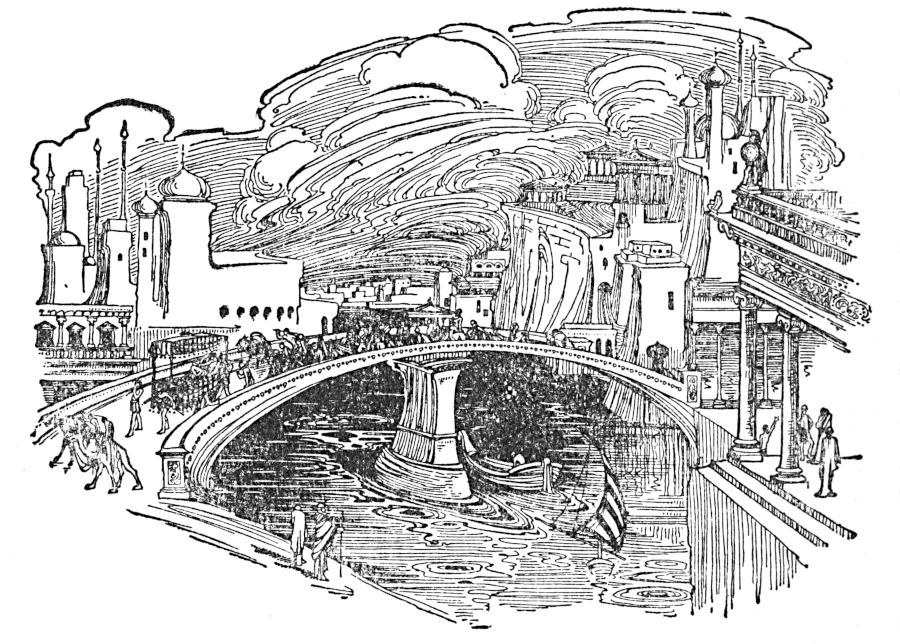

At the word seven, the children looked again, and together uttered a long Oh! of astonishment at the change which had taken place. There was the island indeed, but no longer bare and uninhabited. A gleaming bridge joined it on the land side to a city whose temples, open-air theatres, statues and monuments shone white and splendid in the sunshine. The whole, including three sides of the island, was enclosed by a mighty wall with turrets at intervals upon it, and the water space between the island and the city was now a harbour in which ships rode at anchor.

“There stands Alexandria as I built it over two thousand years ago,” said Dinocrates, quietly. “And there, bearing the same name, the name of Alexander the Great, it stands to-day. English sailors anchor their ships in its port, many English people live there, and it has heard the guns of the Great War that is just over.”

“Not like Babylon, or Ephesus—all in ruins,” murmured Rachel. “Alexandria has lasted.”

“It has lasted—but it no longer looks as you see it here. Time and change! Time and change!” murmured Dinocrates, softly. “It is a modern city now, and most of what I built is ruins beneath its present squares and houses.”

“But there’s no lighthouse—even as we see the place now,” exclaimed Diana.

“There was no lighthouse even in my time, little child. It was not till I had been dead twenty years and more that the beacon tower was built.”

Rachel glanced at him. “After you had—gone on? Gone into another life, you mean?” she said.

Dinocrates smiled kindly at her.

“That is a better way of saying the same thing, little maid,” he agreed.

“But you promised you would tell us about the lighthouse,” began Diana, after a moment. “Do tell us, please,” she urged.

Again Dinocrates smiled.

“I am coming to it, impatient one,” he began, when Rachel interrupted.

“I want to know all sorts of other things first,” she declared. “Did Alexander live here after the town was built?”

“Nay, and he never saw more of the city than its beginning. He was marching always from country to country, conquering the world, and had no time to return to the place which bears his name. Though, after all, I am wrong. He did come back. But when he came, Death, not he, was the conqueror. He died in Babylon, but they brought him hither, to the city built at his command, and here he was buried.”

“Was his lovely horse dead by that time?” asked Diana. “I hope so. Because he would have missed his master.”

“Why, yes,” put in Rachel. “Don’t you remember that Alexander buried him and named a town after him?”

“Of course! How silly of me....” Diana turned expectantly to Dinocrates.

“And about the lighthouse?” she persisted.

“Our ship is about to enter the harbour,” said their companion. “We will land, and go to the spot where the lighthouse finally arose. There I may best tell you its story.”

In a few moments the little vessel on the deck of which they stood, had been safely steered into the harbour between the island of Pharos and the city. At a quay running alongside of the island, they stepped off the ship, and “Dinocrates” led the way to a rock jutting out into the sea. It was a position from which there was a view of the busy harbour, and of the long bridge joining the island to the city, over which passed continually a gaily coloured crowd. Mules with gaudy trappings were driven by shouting boys. Ladies in silken litters were borne along by dark-skinned slaves. Men dressed in tunics like the one worn by “Dinocrates” sauntered by, and from the city itself came a confused hum of voices.

By turning their backs to the bridge the children found the blue sea almost at their feet, stretching away to the distant horizon.

Dinocrates began to speak again, and the water lapping against the rocks close at hand murmured between the pauses of his story.

“There lies the city I began to build while Alexander was yet alive,” he said, pointing backwards over his shoulder. “I was a famous architect in those days, and rich men sent me their sons to learn from me. But among all my pupils the best, the most brilliant, was Sostratus. He came to me when he was but a lad, and I early foretold for him a great career. I loved him dearly, and he was to me like a son. His native land was Greece, and, though he spent some years with me during the building of Alexandria, he returned more than once to his home, and on one of these visits fell deeply in love with a beautiful Grecian maiden.

“Never shall I forget the happiness of Sostratus, when he told me that the maiden, with her parents, was coming to Alexandria, where the marriage was to be celebrated. All was prepared for the bride, and on the appointed day, she set sail to cross the stretch of sea between Greece and Alexandria. But, alas, the weather, till then calm and peaceful, suddenly changed. A great storm arose, and the ship, when it came into sight, though it held bravely on, was tossed like a cockle-shell upon the waters.

“Now this bay of Alexandria is difficult of navigation, and in the darkness, full of danger. Night came on; there was no friendly beacon fire to show the way, and presently we, who were gathered here on this very spot, heard the shouts and cries of drowning men. Powerless to help, we waited in despair for daybreak, only to see the waters strewn with wreckage. Close to land, the good ship, with all on board, had gone down for lack of a light to show the captain where lay the treacherous rocks.

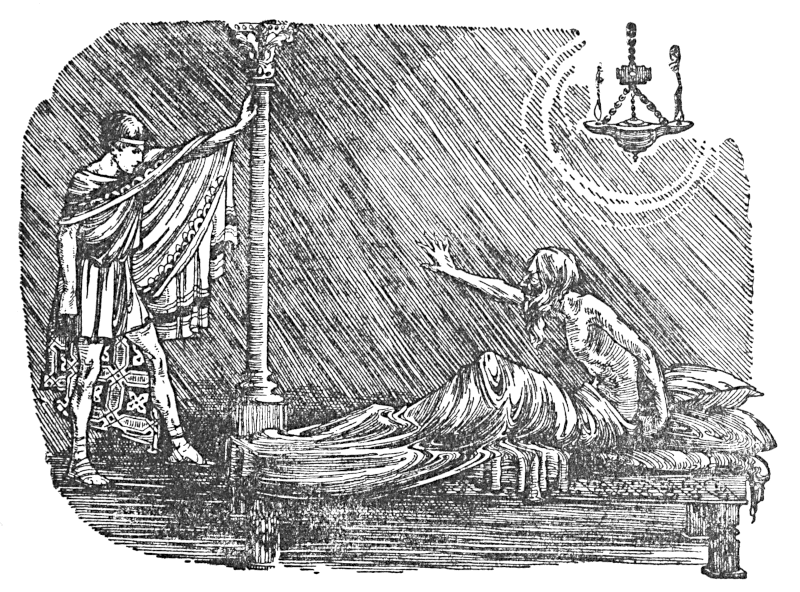

“Sostratus was wild with grief, from which, as time went on, I strove in vain to rouse him. Nothing I could say or do would comfort him, till at last, when I was ill and near to death, I called him to my bedside and urged him not to waste his life in useless idle despair.

“‘Build something,’ said I, ‘which shall be at once a monument to the memory of your bride, and of use to the living. So shall you not have passed through this your present life in vain.’

“‘What if I should build a light-tower?’ he asked presently. ‘Something that shall serve as a beacon and a warning to sailors? Already has the thought of such a tower begun to take shape in my mind, and now, O master, I swear to thee that I will not rest till such a building arises, for by such means, grief such as I have endured may be spared to others.’

“With that he began to discuss with me how such a tower, the first of its kind, could be constructed so that a light should stream constantly from its summit during the darkness of the night. And I, seeing him roused from his grief and ready for a new interest, passed some days later, happily from that life. All that follows, I learnt long afterwards when once more I returned to this earth.

“Even before my own death, Alexander the Great had passed away, and the world he had conquered was being divided amongst the generals who had fought under his command. This land of Egypt, with Alexandria as its port, fell to one of them—a man whose name was Ptolemy. (He it was who helped the Rhodians against Demetrius in the famous siege),” he added, turning with a smile to Rachel.

“And you were Cleon then—not Dinocrates,” she exclaimed quickly. “You remember I told you about that siege, Diana?”

Diana nodded. “But do go on about Sostratus,” she begged, turning to Dinocrates. “Ptolemy let him build the lighthouse, I suppose?”

“After my death,” continued their friend, “my pupil went to King Ptolemy with his plans, and he was ordered not only to set about the building of the tower, but to spare no expense and to make it the most beautiful monument he could possibly accomplish. So Sostratus worked and thought and invented, and in time, on the very spot where now we are seated, there rose the tower you beheld a short while ago. Four hundred feet high it towered above this rock, built of white marble, slender as a lily, yet strong as steel. And in the cup-like hollow at the top, was sunk a brazier, that is, a huge basket of iron in which a fire was kept always burning. The men who from the gallery around this hollow tended the fire and fed the flames, were the first lighthouse-keepers, and the tower itself, being the first lighthouse, was the model for others all over the world. The lighthouse on the spur of land at St. Mary’s Bay, little maids, owes its existence to the marble tower of Sostratus, as in like fashion do all the other famous lighthouses of modern days, such as Eddystone, the North Foreland, and the rest. No longer, it is true, do naked flames stream upwards into the darkness from these modern towers—for, in two thousand years other light has been invented, as well as shielding panes of glass. Nowadays, strong electric globes shoot forth their gleams over the sea at night. But the tower of Sostratus was not only the first of these friendly beacons but also the most beautiful as a monument. So beautiful, indeed, and in those early days so strange to the sight, that it was named amongst the Seven Wonders of the World.”

“Was it called the Tower of Sostratus?” asked Rachel.

Dinocrates smiled and shook his head.

“Nay,” he returned, “though that was the wish of Sostratus himself. It was called the Pharos Tower—after the name of this island upon which it stood.”

“Why,” exclaimed Diana suddenly, “phare is the French word for lighthouse. Is that because of the Pharos tower?”

Diana had a French governess, and to Rachel’s wonder and admiration, spoke French, if not as well, at least as quickly as she talked in English.

“Yes,” answered Dinocrates. “Every time French sailors use that word, even though they have no knowledge of its meaning, the work of Sostratus is mentioned by men who live to-day. His work is remembered, his name forgotten, even though he strove hard that this should not be the case.

“Listen, and I will tell you what chanced. When the tower was at length finished and stood gleaming white on this headland, the time had come for an inscription to be placed upon it, and Ptolemy, King of Egypt, ordered Sostratus to engrave these words upon the marble: King Ptolemy to the gods, the saviours, for the benefit of sailors.

“Now Sostratus, to whom the lighthouse represented all that he now cared for in life, was determined that his own name should be read, if not at the moment, at least in time to come. Yet he dared not disobey the King’s command. This, then, was the device by which he tried to ensure remembrance.

“Deep in the marble he first engraved:

“‘Sostratus, son of Dexiphanes, to the gods, the saviours, for the benefit of sailors.’

“Having thus placed his own, instead of the King’s name upon the tower, he then covered up the whole inscription with mortar, and on the top of it engraved the inscription commanded by Ptolemy. Well he knew, that in the course of years, the mortar would decay and his own name become visible.... Rise, make seven obeisances towards the sea, and you shall behold, if it please you, the lighthouse as it appeared a hundred years after Sostratus and King Ptolemy alike had left this world.”

The children lost no time in obeying, and when they opened their eyes they found themselves, to their delight, standing at the foot of the beautiful white tower. Dinocrates, smiling, stood beside them, and pointed to some lettering upon the tower at a little height above his own head. The inscription was cracked and defaced, and as the words were in Greek, they could not read them, but in a hollow, where the mortar had broken away at the beginning of the sentence, they saw a name which Dinocrates pronounced aloud—the name of Sostratus, now at last plainly to be seen.

The children gazed with interest upon the splendid graceful tower springing high above their heads, and then looked from it across the bridge to the city.

“Why, the town is ever so much bigger. Twice, three times as big,” cried Rachel, as she saw the clustering houses and let her eyes wander over the new domes and colonnades, courtyards and gardens visible on the other side of the harbour.

“A hundred years have passed between the opening and shutting of your eyes,” said the voice of Dinocrates. “The city founded by Alexander and built by me has had time to grow and to become one of the most famous homes of learning in the world. There great men have lived and died, and been forgotten, even as Sostratus, despite this inscription made in vanity, is forgotten. But Alexandria still lives, though the Pharos Tower, the Wonder of the World, is no more. And there, to-day, men who have fought in this last great war are planning to dig for buried treasures under modern houses and squares. Time goes on and men are forgotten, but the work of their brains lasts longer, and sometimes bears fruit centuries after they themselves have departed.... Here, for instance, we stand in this modern lighthouse....”

It was Mr. Sheston (no longer in the guise of Dinocrates) who uttered the last words. Dinocrates, the Pharos Tower, the City of Alexandria had vanished, and a moment later Rachel and Diana were listening to the sailor-man.

“I don’t know who invented them,” he was saying, as though in answer to a question, “but, whoever it was, he did a good piece of work. There’s too many wrecks as it is, but there’d be a considerable number more if it wasn’t for these ’ere light-’ouses.”

“