FIFTH WONDER

THE MAUSOLEUM OF ARTEMISIA

It was fortunate that Diana lived so near. Her father’s house was in fact scarcely five minutes’ walk from Aunt Hester, and the two little girls whose acquaintance had begun so wonderfully began to see a great deal of one another.

They had, as you may imagine, much to talk about, and, when they met, the conversation always turned upon the amazing adventure they had lately shared.

“Oh, Rachel, did you notice the tiny little girl with the red hair who walked next to Dinocrates in the glade—when they put the poppies on the altar?” or, “Do you remember the lovely dress the priestess had? The one who carried the silver dish in the temple?”

Questions and exclamations such as these flew between Rachel and Diana, each one reminding the other of something she had noticed particularly, in the magic scenes beheld from the schoolroom window.

They were, of course, very careful to keep their talks strictly private ones, and Aunt Hester sometimes wondered why such quiet reigned when they were alone together. She was however, very glad that Rachel had found a companion, for she had been rather anxious about having her little niece to stay with her for so long a time as seven weeks. “You see, I haven’t had anything to do with children for years, and I was afraid she would be very dull here,” she told her friends, “but old Mr. Sheston, who seems to have taken a great fancy to the child, has been a godsend, and now that there’s this little Diana as well, I feel I need not trouble about Rachel any longer. I can’t imagine how the old man manages to interest children so much in the British Museum,” she often added. “When I was her age, though, of course, I don’t tell Rachel so, there was nothing I hated more than to be taken to a dull place like a museum. But these two, Rachel and Diana, are always clamouring to go. It’s very strange.”

It was. And even stranger than Aunt Hester thought, as Rachel and Diana could have told her. But of all that made the Museum literally a place of enchantment to the children, she naturally had no idea, nor did she know that without “Sheshà” and his magic, they would probably have been as little pleased with museums as she herself at their age.

It was a wet afternoon, and Diana, who had come round to tea with Rachel, sat perched on the corner of the table, her usual seat, while every now and then she cast a quick glance at the door.

“Do you think he’ll come?” she asked for the twentieth time. “It’s raining so horribly that perhaps he won’t.” (He always meant Mr. Sheston nowadays).

“Oh, I expect he’ll drive up in his car soon,” said Rachel. “It’s seven days since last time, and I’ve never yet missed seeing him on the seventh day. Somehow or other I’m sure we shall have an adventure. Only you never know beforehand how it’s going to happen. And it generally happens quite suddenly, and just when you don’t expect it.”

The afternoon wore on, tea-time came. Still no Mr. Sheston, and at last, when it was almost dark, Diana was obliged to go.

She was almost tearful as she said good-bye.

“It’s so awfully disappointing,” she wailed. “Perhaps it’s all over—all the magic, you know, and we shall never see any lovely things again.”

Rachel was just as puzzled, but not quite so hopeless as Diana.

“Anyhow, even if the magic part is over, he can go on telling us stories,” she observed. “And his stories are splendid. That one about the Siege of Rhodes, you know. I tried to tell you, but I can’t do it properly. Perhaps he’ll tell you himself some time or other. I did think we should have had at least a story to-day,” she added, mournfully.

Rachel repeated this remark to herself as she lay in bed several hours later. The rain had ceased, and a full moon shone in a clear sky. She had pulled up her window blind, and the beautiful silvery light came pouring into the room and made her long more than ever for the magic which Diana feared was “all over.”

For a long time she lay with wide-open eyes staring out of the window at the radiant sky. And then, all at once—how was it? How could it be?—she found herself looking at something quite different.

What was that strange shape high up above her head?... Where was she? What had become of the bed in which a second ago she had been lying? How did it happen that she was standing upright, gazing about her, in what seemed a vast hall filled with moonlight and shadows and dim forms?

She heard a voice—Diana’s voice, surely!

“Where are we? I can’t understand anything. Can you?”

Rubbing her eyes, Rachel looked again. Yes! Diana was beside her. She too was in her nightgown, and they were both standing on the pavement of some huge room which stretched away right and left into darkness. It certainly ought to have been frightening to find oneself all at once in an unknown place surrounded by mysterious shapes, in the middle of the night. But curiously enough, Rachel was not in the least frightened, nor, judging from her voice, was Diana. Both children were deliciously excited, indeed. But of fear there was not in either of them a trace.

“Do you know I believe it’s the Museum,” Rachel whispered. “Only it’s a part of it I’ve never been to before.”

“What’s that big thing up there?” returned Diana in an answering whisper. “Let’s come back a little—we shall see better.”

They were standing just under something that looked in the half light like a great block of stone on the top of which there was an object which neither of them could see distinctly.

Taking hands they moved backwards a few steps, and again looked up.

The silver-green moonlight, streaming in from some window high above their heads, fell full upon the face, and part of the body of a marble horse.

The statue aloft upon its pedestal looked very grand and majestic. But, as even in the dim light, the children could see, it was only after all a fragment of a statue.

“What a lovely horse. But he’s broken,” exclaimed Diana, still in a low voice. “Isn’t it a pity? There’s only his face and a piece of his body left. I wonder how he got broken?”

Before she had finished speaking, Rachel suddenly squeezed her friend’s hand with a tight clasp.

“Look! Look!” she whispered, scarcely able to speak for excitement. For the strangest thing was happening. A kind of pearly mist was gathering to form the missing body of the horse, and presently out of the mist, his face, no longer a marble one, but quivering with life, looked out. He shook his head and the metal curb in his mouth rattled as he fixed his great dark liquid eyes upon the children.

“He’s coming down,” cried Diana, half excited, half afraid.

Quickly she leapt back to make room for him, dragging Rachel with her.

In less than a second, with a bound so rapid that they could scarcely see how he left the pedestal, a graceful, beautiful white horse stood on the pavement before them, gently pawing the ground, and moving his head slowly from side to side.

And then, marvel of marvels, he spoke.

“Have no fear, O little ones,” they heard, in a tone soft, yet distinct. “I am here at the bidding of your friend, Sheshà—greatest of magicians.”

Rachel glanced triumphantly at Diana, as if to say, “I told you so.” And the beautiful steed went on:

“For this one night I am your slave. Command me. What is it you wish to know, or to see?”

Diana pinched Rachel’s wrist as a sign for her to speak, and after a moment she said timidly:

“We would like to know about you first. Why were you on that pedestal? And all broken? Where do you come from?”

“Something of my history, little maidens, you shall hear later. For the present, be content to know that you behold in me a horse as famous as he is beautiful.”

This was said very simply, and the children could well believe its truth, for never had they seen such a lovely creature as that now standing before them.

His coat, smooth and soft as ivory satin, gleamed in the moonlight. His limbs were strong, yet formed with perfect grace, and his dark, lovely eyes shone in a face that was at the same time gentle and full of intelligence.

“I don’t wonder that someone made a statue of you,” exclaimed Diana. “But what a pity it’s so broken. How did it get broken?”

“Many things get broken in the course of two thousand years and more, little one. Since I was first carved in marble, much that was beautiful has been destroyed, either by man, by earthquake, by fire, or other calamities.”

He sighed and turned his head restlessly as he glanced right and left about the great hall. Rachel and Diana, who till now had been too engrossed by his marvellous and sudden appearance to pay attention to anything else, now followed his gaze, and saw that the hall in which they stood was filled with fragments of buildings, with broken statues, broken columns, stone or marble lions and other wild animals, all more or less damaged.

“Behold!” exclaimed their strange companion, after a moment. With a movement of his head, he indicated something which stood on a massive block near him, and the moonlight was so bright that the children saw the object plainly.

“It’s a big wheel!” cried Diana. “What is it?”

“One wheel of the chariot to which my statue was harnessed ages and ages ago!”

“But where? Why? Do explain all about it,” cried Rachel, eagerly.

“Would you see the monument itself of which these columns, these statues, these poor broken things are but the fragments?”

“Oh, yes!” returned the children, both together. They glanced at one another rapturously, for evidently this adventure was to be continued.

“Your wish shall be granted,” said the lovely creature. “But first, that you may gaze upon one of the Wonders of the World with greater interest, look round you and behold, here, where you stand, the poor scattered remains of its beauty.... Take note of those statues facing you, for defaced, disfigured as they are, they represent a famous king and queen.”

The children looked up obediently at two gigantic statues of a man and a woman, both clad in robes beautifully draped, who stood side by side on a great block of stone. Scarcely anything was left of the woman’s face, though the head of the man was almost perfect.

“You behold Queen Artemisia and King Mausolus,” said their new friend. “Now turn and regard that pillar behind you.”

The children looked in the required direction and saw, flooded in moonlight, a tall, beautifully fluted column, to which was attached a piece of broken ceiling.

“That was once part of the monument you shall presently see as it looked in its first beauty,” he continued. “Come, mount upon my back. We tarry too long in this narrow place where there is scarce room to move, encumbered as it is by these fragments of the past. Let us away to sunshine and blue sky!”

THEY HAD A GLIMPSE OF THE CITY

Very gently and carefully, so that he did not touch any of the objects close to him, the snow-white horse knelt down, and, with a shake of his bridle, invited the little girls to climb on his back. They glanced at one another, rather afraid, but Rachel, after a moment’s hesitation, went boldly up to him and, holding tight to his mane, scrambled on to his back.

“Come along!” she called to Diana. “It’s always all right when Sheshà manages anything, and he’s managing this.”

Taking courage, Diana followed, and, in a moment, both children were seated.

“Well done!” exclaimed their steed. “Have no fear, little maidens. You are safe. No harm shall befall you.”

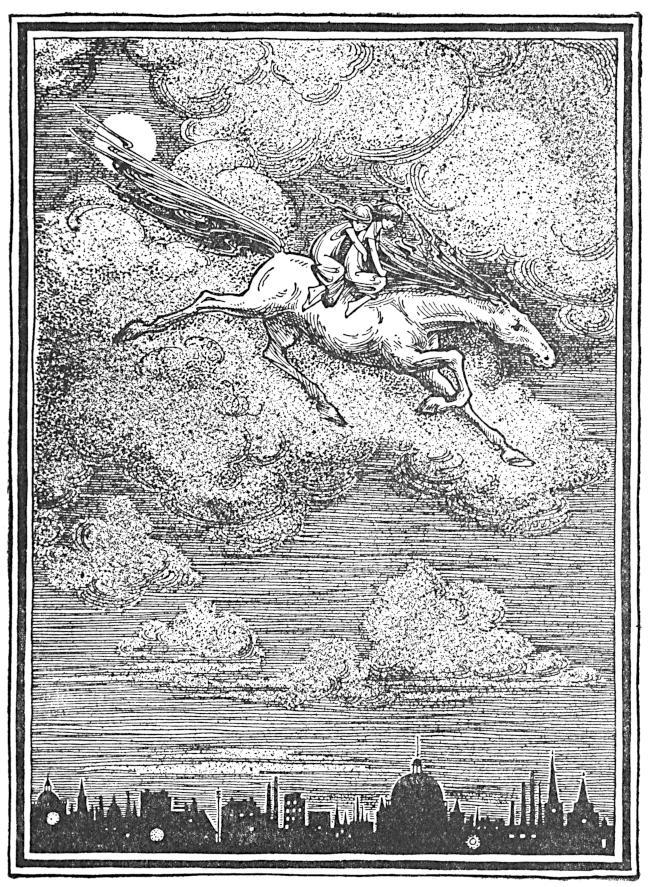

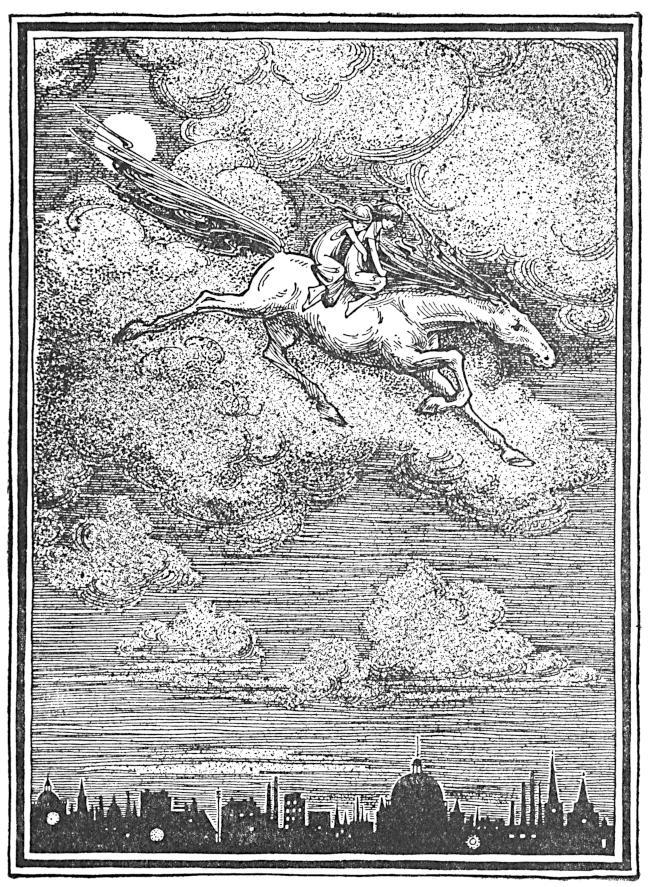

With the last words he began to rise from the pavement, floating slowly upwards.

“Oh! we shall bump against the ceiling!” began Diana, in alarm.

“No. Look! look!! There isn’t any ceiling!” cried Rachel. “It’s all melted away, and there are the stars....”

In another second they were out in the open air, seated as comfortably on the back of the white horse as though they were on the schoolroom sofa, and feeling quite as safe. Below them lay the roof of the British Museum, and beyond it, stretching for miles and miles, all the crowded roofs, the spires, the domes and the lights of London. For a moment they had a glimpse of the wonderful city lying silent under the moonlit sky, and then they soared upwards so high that all sight of it was lost.

“We’re going awfully fast,” whispered Rachel. “Isn’t it perfectly lovely?”

And Diana sighed in perfect content. For, indeed, it was beyond all words wonderful to be rushing through soft, warm air under the moon, and to feel the gentle rocking motion of the horse’s body under them. Faster and faster they flew through the ocean of air, and the children screamed with delight when now and again their giant shadows were thrown for a second upon a white cloud as they shot past in their flight.

On and on fled their magic steed, moving his limbs in the sea of air as a swimmer moves in water, his beautiful mane streaming like a white mist behind him.... Gradually the moonlight faded, and, for a time, only the stars shone in the dark blue sky.

“We’re flying over the sea now. I can hear it!” whispered Rachel presently, for they had dropped lower by this time, and a deep murmur and even every now and then the gentle splash of waves could be distinctly heard.

“It’s getting light,” answered Diana, in a sleepy voice.

There was silence for some time, and perhaps both children fell asleep, for, almost at once as it seemed, instead of a grey gleam of dawn, they saw that the sky was all flushed with rosy light, and everything was now clearly visible.

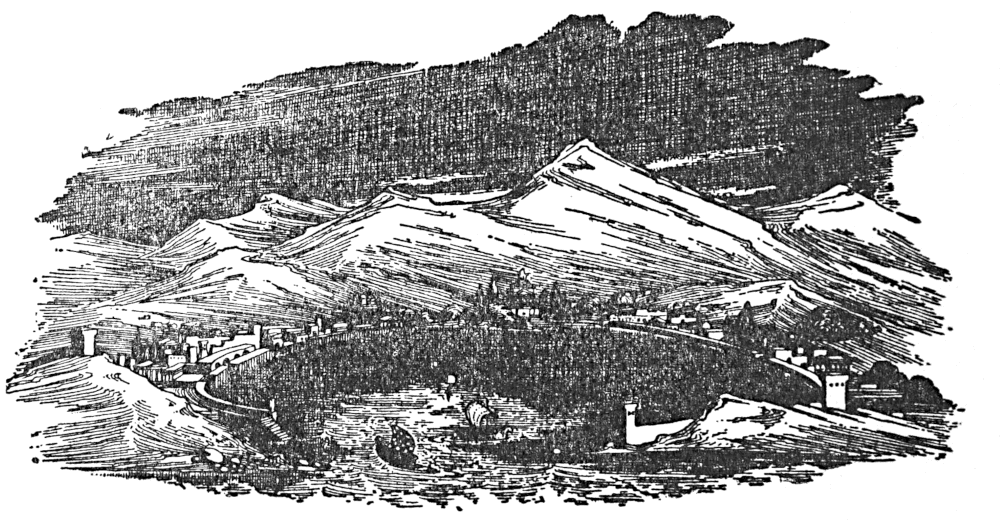

“Look! Look!! We’re quite close to the land!” cried Rachel, pointing to where rocky mountains stood up against the sky. “Oh, Diana, isn’t it beautiful?”

By this time they were hovering above a white-roofed city, curving round a beautiful blue bay.

“Where are we?” begged Rachel, leaning forward to speak to their flying steed, who was now moving slowly.

“This land, O child, is Asia Minor, and the part of it you now see was called long ago, when I was young, Caria. The city just below us is Halicarnassus.”

“Then the sea is the Mediterranean, I suppose?” said Rachel. “And we are not so far from Rhodes?”

“Yonder is the island of Rhodes,” he answered, turning his head in its direction. “You can see it, a dim shape on the horizon—not so very far, as you say, from the city of Halicarnassus.”

“Oh! what is that?” exclaimed Diana, suddenly catching sight of something gleaming white through a grove of trees at a little distance.

“The very monument I have brought you to behold. A Wonder of the World. The place where, carved in marble, my image once stood beside the statues of a king and queen. Come, let us approach it.”

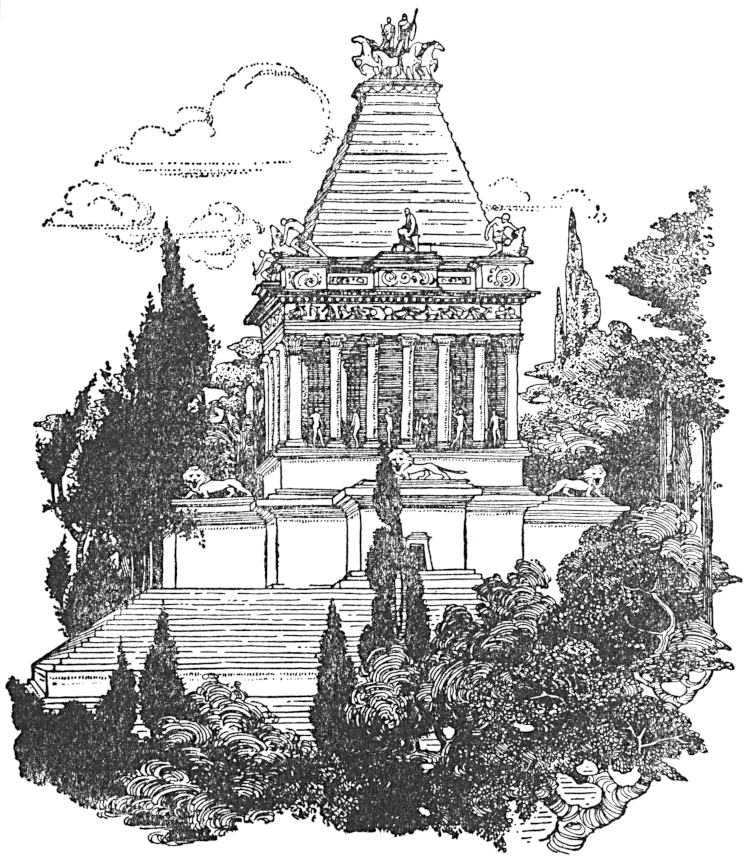

Turning a little aside from the city itself, the horse dropped gradually lower, and, after just skimming the ground for a moment, allowed his hoofs to touch it, and finally stood motionless in front of a lovely building.

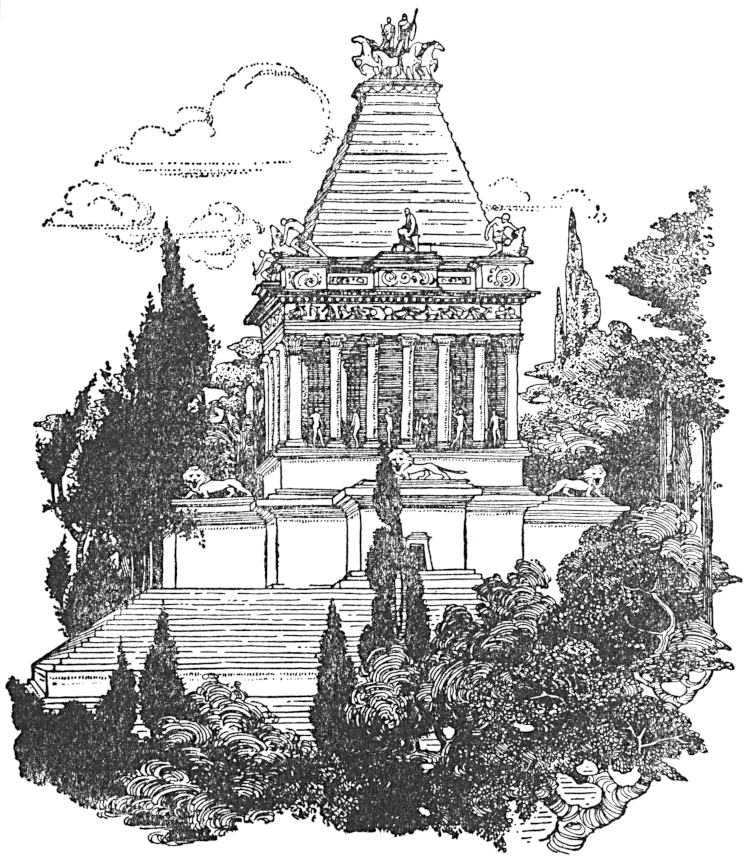

A stately flight of steps, whose balustrade was guarded by marble lions, led up to a square tower, and higher still to a cluster of beautiful columns. Above this was a sort of pyramid, with steps mounting yet again to a chariot of marble in which stood two figures, a man and a woman. The chariot was drawn by magnificent horses, and as the children looked at these, they cried out together, pointing to them, eagerly:

“Why, they’re all of them—you!” exclaimed Diana. In her excitement she let herself slip easily to the ground. Rachel followed her example, and both stared up at the group of horses on the summit of the building.

“What we saw in the Museum before you turned into a real horse is just one head of you!” cried Rachel. “Then those people in the chariot must be the broken statues that are also in the Museum—I mean before they were broken?” she went on.

The steed bowed his head. “You are now beholding the statues of Queen Artemisia and King Mausolus as they appeared soon after the sculptors had finished their work. There also you see my image as it, too, appeared nearly three thousand years ago. Or, rather, my image four times repeated in each of the four horses.”

The children were at first silent, for amazement and admiration held them spellbound. The sun was rising, and bathed in its light, the building was more lovely than tongue can tell.

“It’s like a tower in a fairy tale. The kind of tower a magician builds, you know!” declared Rachel, at last.

“But what is it for?” added Diana, after a moment.

“It is a tomb, little maid.”

“A tomb?” echoed Diana. “All that great big beautiful place only for a tomb?”

“The great Pyramid was a tomb,” Rachel told her in an aside, “and that’s bigger, you know. Whose tomb is it?” she went on.

“Would you hear the whole story? I am here to tell it, if that should be your wish. Let us then rest in the shade of these cypress trees while you listen.”

Their guide lay down and stretched his beautiful body at full length on the soft turf, while the children, with their hands clasped round their knees, sat facing him, eagerly waiting for him to speak.

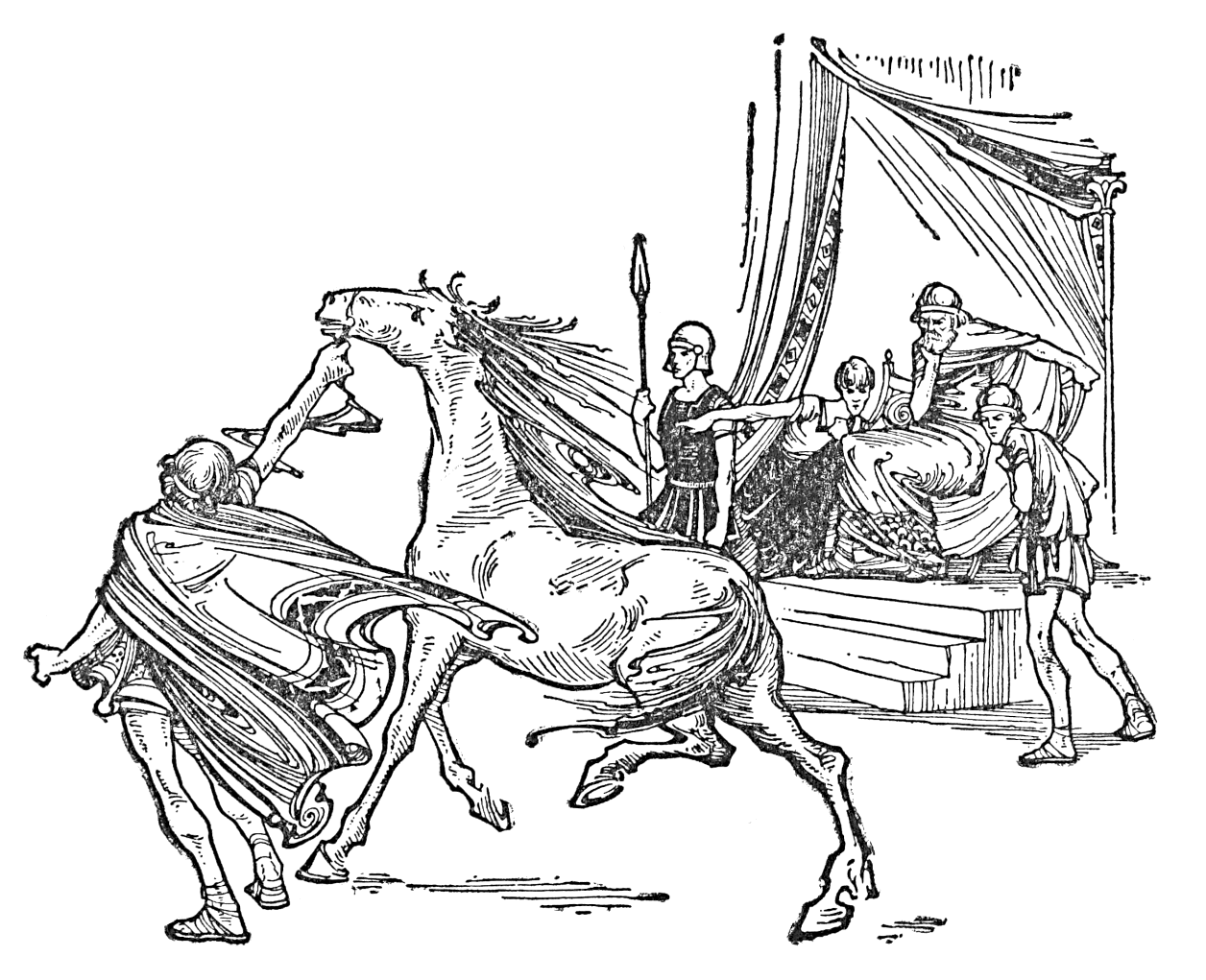

“I cannot, O little maidens,” he began, “relate to you the history of this magnificent tomb without telling you something of my own story, which is in a way bound up with it. Already it must be clear to you that I am no ordinary horse. The time has now arrived when I may reveal my name. Know, then, that I am no other than Bucephalus, the famous steed of the greatest conqueror in the world, Alexander the Great.

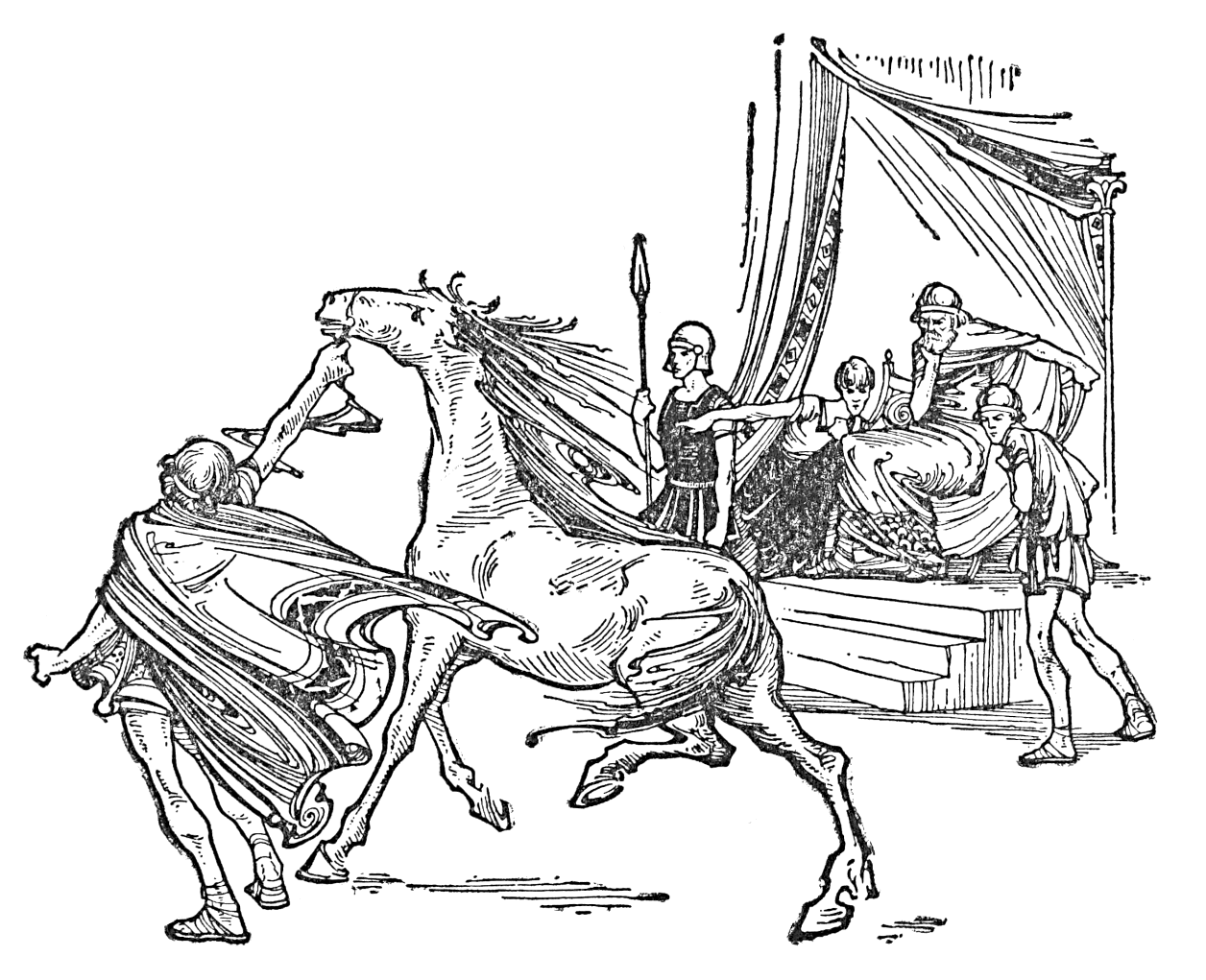

“I was born in Greece, but when I was still very young, I was sent as a gift to the King of Macedonia, a country bordering upon my native land. As yet, no man had ridden me, and being young and untried, I was so impatient of control that when the king would have mounted upon my back, I reared and plunged, lashing out with my hind legs in a fashion so dangerous and unseemly that no one might approach me.

“Full of anger at my fierce behaviour, the king was ordering me to be sent back whence I came, when his son, the young Prince Alexander, cried out, ‘This is a noble horse! Will you lose him for lack of a little skill and courage? Give me leave, my father, to make trial of him.’

“At first the king, afraid for his son’s life, refused, but, the entreaties of Alexander at last prevailing, he gave consent for the prince to approach me.

“At once the noble boy drew near, and boldly seizing me by the bridle, turned me about so that my face was to the sun. For he had the wisdom to perceive that what had terrified my foolish young heart was nothing but my own shadow. This, now that the sun was not at my back, I could no longer see, and gradually, as I felt the prince’s kind hand patting my neck and stroking my glossy hide, I ceased to tremble. But, even so, such was my folly and youthful pride I would not have allowed him to mount if he had not with great skill taken me by surprise. As it was, before I had time to consider, I felt him already on my back, and, bounding forward in anger, I began to run like the wind. Far from making any endeavour to check my speed, the prince, without touching me with whip or spur, urged me on with ringing shouts of encouragement, and not till I was worn out did he draw rein. By that time I was his slave. His voice, his gentle touch had tamed me, and with delight I accepted him as my master. Never shall I forget how the king and his courtiers who had been struck dumb with fear while I raced like a mad thing, Alexander upon my back, now gathered round, praising us both.

“The king, embracing the prince, exclaimed, as I remember: ‘My son, seek a kingdom more worthy of thee, for Macedonia is not sufficient for thy merits!’

“This advice as perhaps I need not remind you, Alexander was not slow to take, for a few years later, when his father died and he became King of Macedonia, he began those conquests which have made him for ever famous. Soon nearly all the world that was then known owned his sway. In all his victories I, Bucephalus, had my share, for I carried him into every battle. No one but my dear master would I allow to mount me, and, in order that he might do this the more easily, it was my custom to kneel down upon my forefeet as soon as he was ready to bestride me—just as some little while ago I knelt down for you, little maidens.

“Ah! those were happy days when we went out to conquer, and great was my joy in battle. I felt no fatigue when I carried Alexander into the fight, and no horse ever loved a master so well as I loved mine. No master on the other hand was more devoted to a steed than Alexander to his. What other horse, I pray you, has given his name to a city? Yet of me this may be said, for where at last, worn out in his service, I died, Alexander built a city where he buried me, and called it Bucephalia.”

The beautiful creature sighed, but a moment later recovered himself.

“You will wonder,” he went on, “when I am coming to the story of the noble tomb before you, and what it has to do either with me or with Alexander. This I will now relate. About the time when Alexander became King of Macedonia, there was a Persian king reigning here in this city of Halicarnassus. His name was Mausolus, and he had a beautiful wife called Artemisia, who loved him devotedly.

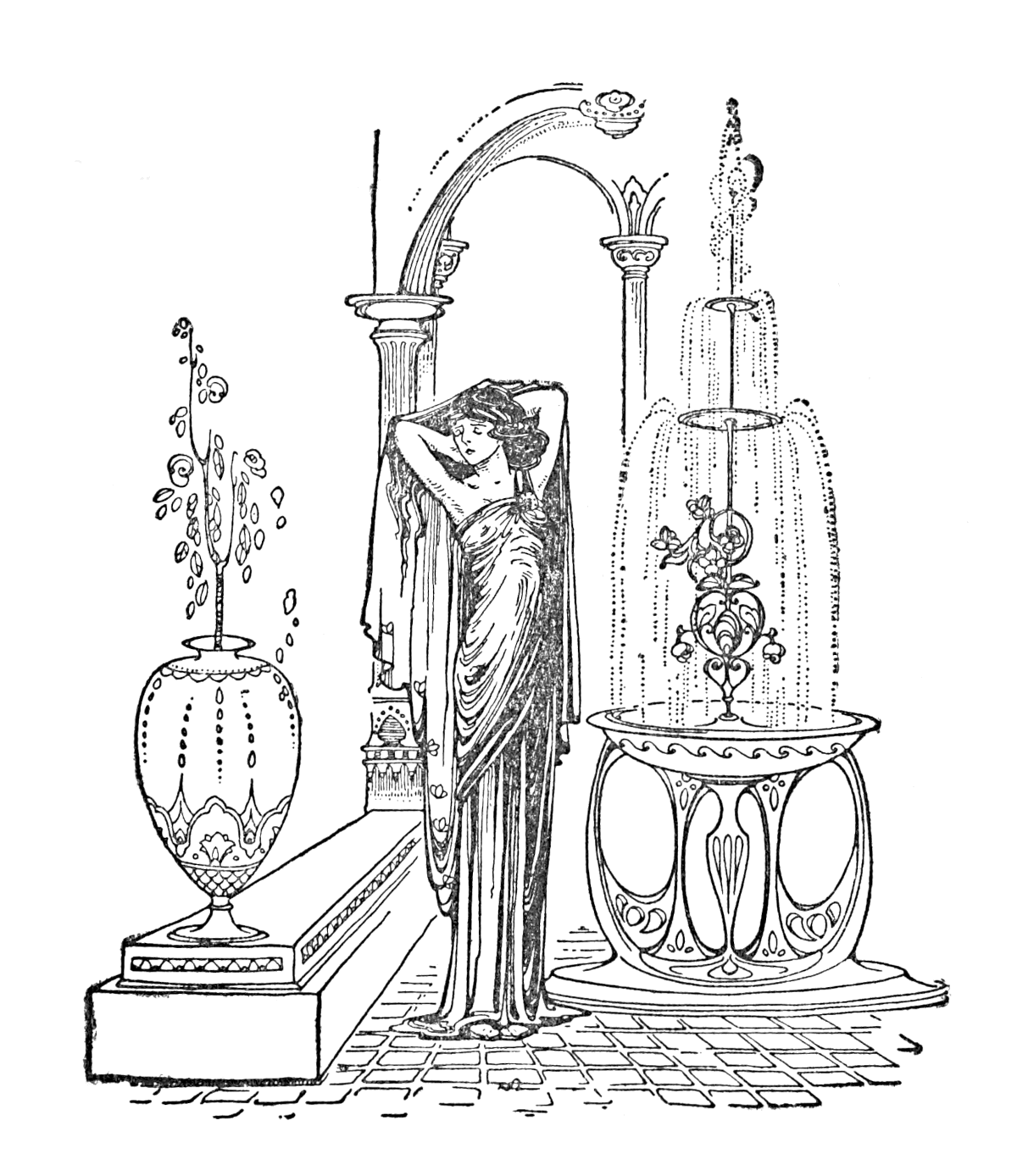

“You, O little ones, who live in modern days in a grey city, where people go clothed in sad colours and walk in dingy streets, have no idea (except from your fairy tales) of the manner in which a Persian king and queen kept their court nearly three thousand years ago.

“Ah, the beauty and luxury I have seen in those Persian palaces!” exclaimed Bucephalus, as though to himself. “The marble courtyards with their springing fountains, the jewelled thrones, the silken robes, men and women alike blazing with precious stones—and over all the glorious blue sky and the splendid sun!” He sighed again, and for a while seemed lost in thought.

“Those days are gone for ever,” he went on at last. “But it was amidst such scenes, in such pomp and luxury as this, that Mausolus and his queen Artemisia dwelt in the city of Halicarnassus. Some years they lived together in great happiness, and then, to the terrible grief of his queen, King Mausolus died. In her despair and misery, Artemisia could think of no other means of distraction than that of building to the memory of her husband so beautiful a tomb that it should be famous throughout the world, and for ever preserve the name of Mausolus.

“She had vast riches, and because she was a learned and enlightened queen, she knew that it was to Greece she must turn to spend her wealth. For in Greece dwelt all the great artists, whether sculptors, architects or poets.

“This tomb raised to the memory of her husband, Mausolus, was to be the Wonder of the World. Not content with one Greek architect, therefore, she employed no less than four to design and beautify the building you see before you, which faces north, south, east and west. Scopas it was who built the eastern side, Leochares the west, Bruxis the north, and Timotheus the south. These were famous men in my day, and even when they had finished their labour, and even when the tomb of Mausolus was surrounded by colonnades, supported by beautiful pillars, and lined with magnificent statues, the queen was not satisfied. The tomb must be still more wonderful, still more stately. So she sent for Pythios, a great sculptor, and ordered him to erect above the temple-like tomb, a pyramid. On the top of the pyramid he was to place a group in marble which should represent herself and Mausolus, standing side by side, in a chariot drawn by four horses.

“Now Pythios was anxious to find as a model for these horses the most beautiful steed in the world. And where, said everyone, could he find a creature more beautiful than the famous Bucephalus of Alexander?

“So Pythios came to our court and sought of my master permission to make drawings of me in varying attitudes as I reared or ran. This being granted, I became the model for all four of the marble steeds who drew the chariot of King Mausolus and his queen Artemisia. Behold them! For in magic fashion you see them as they appeared long, long ago, when this tomb was first completed. Greatly favoured are you, little children, for other mortals now living must be content to gaze only upon those broken fragments of the tomb, which, in recent days, have been drawn from the earth. Long, long ago, was this magnificent monument destroyed, and were it not for my company and the magic of Sheshà, who has called me to this earth once more, you would be looking upon nothing but ruin and destruction here in this place. See how splendidly white and dazzling appears that noble group against the deep blue of the sky! And then contrast it with the battered figures, the one chariot wheel, the broken horse’s head, which is all that now remains. Still more wonderful that such fragments should at last have found their way to your grey city of London—thousands of miles away.”

Bucephalus paused once more, wrapped in earnest thought, which the children scarcely dared to disturb, though they were longing to ask questions.

“You will ask,” he continued presently, “how I, who at the time when this tomb was built dwelt far from Halicarnassus, know all that I have related. Let me explain.

“Though Pythios had taken me as a model for those famous horses of his, I never thought to behold them, and when I have completed the story of Queen Artemisia, I will relate how it chanced that I did at last look upon them with my own eyes.

“The great tomb, so marvellous, so beautiful that it became one of the Seven Wonders of the World, was at length finished—as you see it. A miracle in marble, with the queen herself and her dearly loved husband standing together to endure as she thought for ever. Her task completed, and with nothing else to live for, the queen pined away, and a year later died. The monument she raised, as you know, is shattered to fragments, but, after all, Artemisia’s wish was fulfilled, for the name of her husband, at least in a fashion, yet lives. Ever since her day, every splendid tomb, such as that in which kings or great heroes are buried, has been called a Mausoleum. And when people of the present age speak that word, though they may not be aware of it, they are uttering the name of Mausolus, so dear to Artemisia.

“And now to return to my own history.

“Fourteen years after the death of this unhappy queen, I bore my master, Alexander, into yonder city of Halicarnassus, as a conqueror. He had fought and defeated the sovereign then reigning in Caria, and all the inhabitants of this country did him homage. How well I remember the morning he rode out to see with his own eyes this very tomb of which he had heard so much.

“It was a morning such as this. The sun, just as you see it now, had newly risen, and then, as now, the marble pillars, the chariot group, the statues stood out white as sea-foam against a sky, every whit as deep and blue as you behold.

“Alexander stood transfixed with admiration, and I could not refrain from a glance of pride at my own image, four times repeated on the summit of the building.

“‘Ah!’ thought I, ‘when she ordered those marble horses to be carved by the greatest sculptor of her time, little did Queen Artemisia guess that the model from which they were designed would one day gallop proudly into her city, bearing upon his back the conqueror of her kingdom.’ It was a sad and overwhelming reflection, and, as I gazed upwards at the statue of Artemisia herself, I half expected her to descend in wrath from her chariot to punish my insolence. But, after all, it was Alexander, not I, who had taken Halicarnassus, as I made haste to assure myself, and I turned my head to look in the face of my beloved master. He was gazing sadly at the tomb, and I fancied that, conqueror though he was, he thought with sorrow and pity of the unhappy queen. For as generous as brave was my dear master, Alexander the Great.”

Quite a long silence followed the last words, and it was a silence which somehow the children had no wish to break, for they both felt a little dreamy and disinclined to speak.

“Presently,” thought Rachel, “we’ll ask him to let us go up that splendid staircase and get inside the temple where Mausolus is buried. There must be all sorts of lovely things there.” But at the moment she felt it was enough just to sit still and gaze at the outside of the tomb, at the burning blue of the sky behind it, at the sparkling bay beyond, about which the flat-roofed white houses of the city clustered.

“It will be awfully interesting to walk about in Halicarnassus,” she reflected. “I wonder whether we shall see Queen Artemisia? We might. Anything of course could happen. And it’s all just as real as—as though it was real,” she added, at a loss how to put it to herself. It was just when she had m