FIRST WONDER

THE GREAT PYRAMID

Rachel was a very unhappy little girl as she sat in an omnibus with Miss Moore, on her way to the British Museum. She didn’t want to go to the British Museum. She didn’t want to be in London at all. She longed desperately to be back in her country home with her father and mother—now, alas! far away in Egypt.

Everything as Rachel said had happened so suddenly. Certainly her mother had been ill some time, but it was all at once decided that the only possible place to send her little daughter in a hurry, was to Aunt Hester, in London.

Aunt Hester, who was her father’s eldest sister, and in the eyes of Rachel, at least, awfully old, was quite kind, but also, as she admitted, quite unused to children. The first thing she did therefore, was to engage a governess to look after her niece for the seven weeks she would have to remain with her.

Miss Moore, a rather uninteresting, middle-aged lady, had duly arrived the previous evening, and at breakfast time Aunt Hester had suggested the British Museum as a suitable place to which Rachel might be conducted.

“She’s never been to London before, and, though I don’t want her to sit too long over lessons, I think she should improve her mind while she is here. The British Museum is an education in itself,” declared Aunt Hester, and Miss Moore had primly agreed.

So it happened that at eleven o’clock on a bright spring morning, a secretly unwilling little girl climbed the steps leading to the great entrance of the great museum. The pigeons on the steps reminded her of the dovecote at home, and the tears came suddenly to her eyes, as almost without thinking she counted the number of birds on the top step.

“Seven,” she murmured half aloud.

“Seven what?” asked Miss Moore.

“Seven pigeons on this step. Aren’t they pretty?” Rachel lingered to look at the burnished shining necks. She would much rather have stayed outside with the pigeons, but Miss Moore hurried on to the swing doors, and Rachel was obliged to follow her into the huge building.

“What do they keep here?” she asked listlessly, when Miss Moore had given up her umbrella to a man behind a counter, just inside.

“All sorts of things,” returned her governess vaguely. “It’s a museum, you know.”

Rachel was not very much the wiser but, as she walked with Miss Moore from one great hall to another, she was confused and wearied by the number of things of which she had glimpses. There were rows of statues, cases full of strange objects, monuments in stone all covered with carvings; curious pictures on the walls. Indeed, there were “all sorts of things” in the British Museum! But, as she knew nothing about any of them, and Miss Moore volunteered very little information, she was yawning with boredom by the time her governess remarked:

“Now, these things come from Egypt.”

For the first time Rachel pricked up her ears. Mother and Dad were now in Egypt, and as she glanced at the long stone things like tombs, at drawings and models and a thousand other incomprehensible objects all round her, she wished she knew something about them. Instead of saying so, however, and almost without thinking, she murmured, “This is the seventh room we’ve come to. I’ve counted them.”

“This is the famous Rosetta Stone,” observed Miss Moore, reading an inscription at the foot of a dull-looking broken block of marble in front of them.

Rachel yawned for the seventh time with such vigour that her eyes closed, and when she opened them a queer-looking little old man was bending over the big block.

“What is the date of the month?” he asked so suddenly that she started violently.

“Let me see. The seventh, I think. Yes—the seventh,” she stammered, raising her eyes to his face.

He was so muffled up, that nearly all Rachel could see of him was a pair of very large dark eyes, under a curious-looking hat. He wore a long cloak reaching to his heels, and one end of the cloak was flung over his left shoulder almost concealing his face.

Rachel scarcely knew why she thought him so old, except perhaps, that his figure seemed to be much bent.

“Quite right. It’s the seventh,” he returned. “And what’s the name of your house?”

Rachel looked round for Miss Moore, who strangely enough was still reading the inscription on the stone, and seemed to be paying no attention to the old man’s questions.

“It’s called ‘The Seven Gables,’” she answered.

“And where are you living now?”

“At number seven Cranborough Terrace.”

“And your name is Rachel. Do you read your Bible? How many years did Jacob work for his wife?”

“He waited for her seven years. And her name was Rachel,” she exclaimed, forgetting to wonder why Miss Moore didn’t interfere, or join in a conversation which was becoming so interesting.

“The seventh of the month, and the Seven Gables, and seven years for Rachel—and, why, there were seven pigeons just outside as I came in, and this is the seventh room we’ve come to. Because I counted them. I don’t know why—but I did. What a lot of sevens.”

“Can you think of any other sevens in your life?” asked the little old man, quietly.

“Why, yes!” she answered, excitedly. “There are seven of us. All grown up except me. And I’m the seventh child, and the youngest!”

“Seven is a magic number, you know,” said her companion, gravely.

“Is it? Really and truly?” asked Rachel. “Oh, I do love hearing about magic things! But I thought there weren’t any now?”

“On the contrary, the world is full of them. Take this, for instance.” He pointed to the broken marble block. “That’s a magic stone.”

Rachel gazed at it reverently. “What does it do?” she asked almost in a whisper.

“It’s a gate into the Past,” returned the old man in a dreamy voice. “But come now,” he went on more briskly, “can we remember any more sevens? You begin.”

“There are seven days in the week,” said Rachel, trying to think, though she was longing to ask more about the magic stone.

“There’s the seven-branched candlestick in the Bible,” the old man went on, promptly.

“And the seven ears of corn and the seven thin cows that Pharaoh dreamt about,” returned Rachel, entering into the spirit of the game.

“The story of the Seven Sleepers.”

“The Seven Champions of Christendom,” added Rachel, who had just read the book. “Oh, there are thousands of sevens. I can think of lots more in a minute.”

“It’s my turn now,” was the old man’s answer. “The Seven Wonders of the World.”

“I never heard of them. What are they?” Rachel demanded.

Again the old man pointed to the stone. “That gateway would lead you to one of them,” he said, quietly, “if, as I’m beginning to think, you’re one of the lucky children.”

THE ROSETTA STONE

“Do lucky children have a lot to do with seven? Because if so, I ought to be one, oughtn’t I? It’s funny I never thought about it before, but there’s a seven in everything that has to do with me! And—”

“We’ll try,” interrupted the little old man. “Shut your eyes and bow seven times in the direction of this stone. Never mind this lady”—for Rachel had quite suddenly remembered the curious silence of her governess. “She won’t miss you. You may do as I tell you without fear.”

Casting one hasty glance at Miss Moore, who had moved to a little distance and was just consulting her watch, Rachel, full of excited wonder, obeyed. Seven times she bent her head with fast-closed eyes, and opened them only when her companion called softly “Now.”

Even before she opened them, Rachel was conscious of a delicious warmth like that of a hot midsummer day. A moment ago she had felt very chilly standing before the marble block Miss Moore called the Rosetta Stone, in a big, gloomy hall of the British Museum. How could it so suddenly have become warm?

In a second the question was answered, for she stood under a sky blue as the deepest blue flower, and the glorious sun lighted a scene so wonderful that Rachel gave a scream of astonishment.

“Where are we?” she gasped.

“In the mighty and mysterious land of Egypt,” answered her companion, “as it appeared thousands of years before the birth of Christ.”

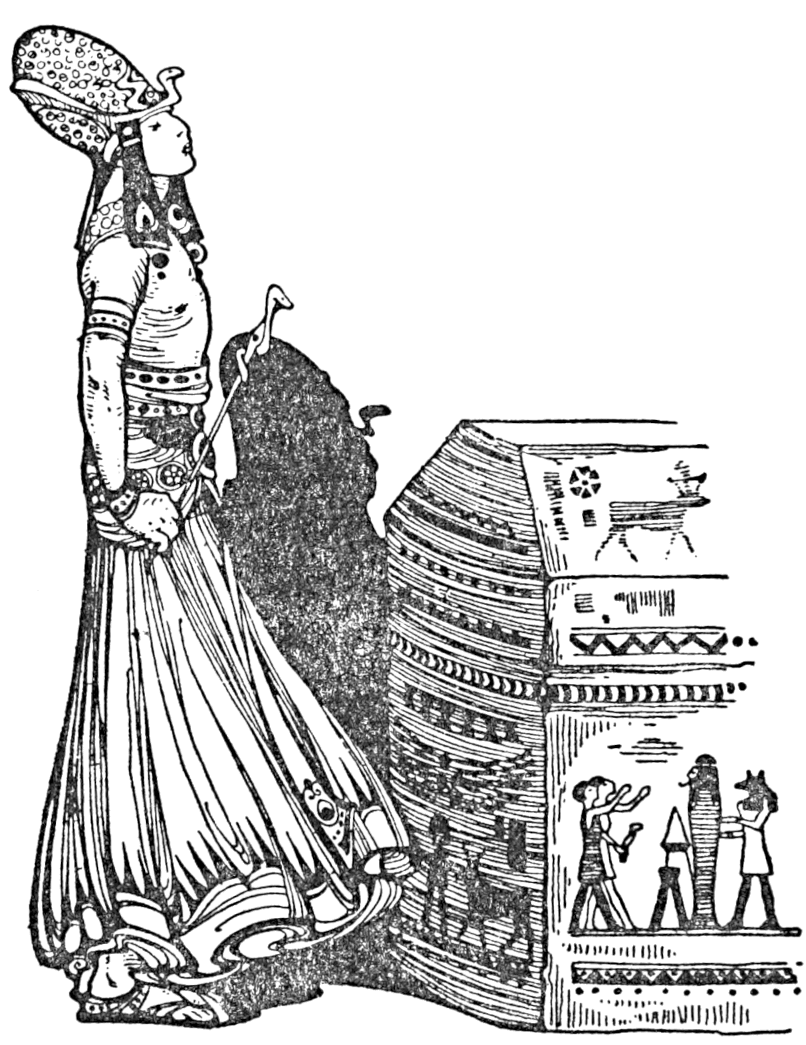

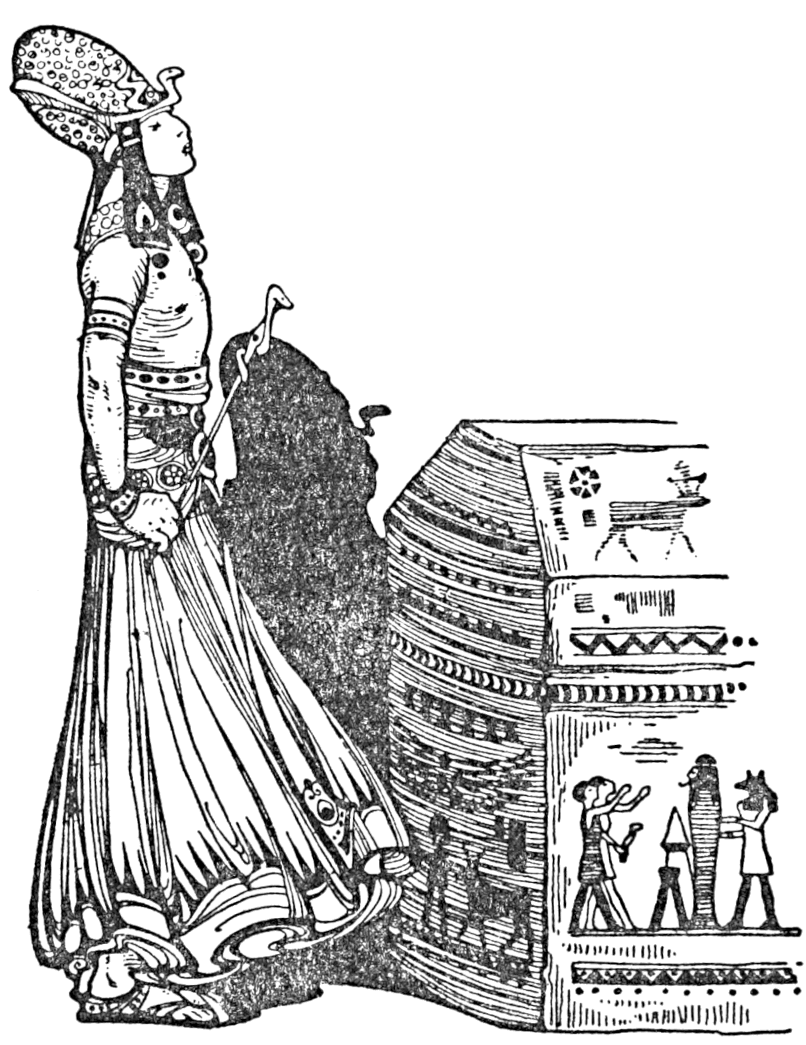

His tone was so solemn that Rachel turned quickly to look at him, and, wonder of wonders, no old man was by her side! A dark-skinned youth stood there, dressed in a curious but beautiful robe with strange designs embroidered on its hem, and a no less strange head-dress, from which gold coins fell in a fringe upon his forehead.

“Oh!” cried Rachel, when she could speak for amazement. “You were old just now. I don’t understand. Who are you?” she added, in confusion.

The young man smiled, showing a row of beautiful white teeth. “My name is Sheshà. I am old,” he said. “Very, very old.” He pointed to a great object at which, so far, in her astonishment, Rachel had scarcely had time to glance. “I was born before that was quite finished—six thousand years ago.”

Rachel gasped again.

“But you look younger than my brother, and he’s only twenty,” she exclaimed.

“In returning to the land of my birth I return also to the age I was when I lived in it.... But now, little maid of To-day, look around you, for there stands, as it stood six thousand years ago, one of the Seven Wonders of the World.”

Rachel obeyed and gazed upon a huge building with a broad base, tapering almost to a point, whose walls were of smooth polished stones of enormous size. Only a moment previously she had glanced carelessly at pictures of buildings like this one, but now, as she saw it rising before her in all its grandeur out of the yellow sand, and under a canopy of blue sky, she almost held her breath.

“It is a pyramid, isn’t it?” she whispered. “I’ve seen pictures of pyramids, but I don’t know anything about them.”

“It is the first great pyramid of Egypt,” answered the young man. “And, little maid, you are highly favoured, for you see it as it looked nearly six thousand years ago. It was already old when Joseph was in Egypt, and Moses saw it when he lived in the palace of Pharaoh’s daughter.”

Rachel gasped. “But what is it? What is it built for?” she asked.

“For the tomb of a king. That pyramid—” he pointed towards it—“was built by the great King Cheops, and because you are one of the fortunate children of the magic number seven, you see one of the Seven Wonders of the World as it stood fresh from the workers’ hands.”

“Dad is in Egypt now. He doesn’t see it like this then?”

Sheshà smiled. “Nay. He has already approached the Wonder in an electric car—like all the other travellers of to-day, and instead of these walls of granite which you behold, graven over with letters and strange figures, he has seen great rough steps.”

“Steps?” echoed Rachel. “Why are there steps up the side now?”

“Because beneath these smooth walls the pyramid is built of gigantic blocks of stone, and now that their covering has been removed, the blocks look like steps which can be, and are climbed by people who live in the world to-day.”

“But why was its beautiful shining case taken off?” Rachel asked, looking with curiosity at the carving upon it.

“Because in the course of long years the people of other nations who conquered Egypt and had no respect for my wondrous land, broke up the ‘beautiful shining case,’ to quote your own words, little maid, and used it for building temples in which they worshipped gods strange and new.”

Rachel glanced again at her companion. She was still so bewildered that she scarcely knew which she should ask first of the hundred questions crowding to her mind. And then everything around her was so strange and beautiful! The yellow sand of the desert, the blue sky, the burning sun, the long strip of fertile land bordering a great river.

“That must be the Nile,” she thought, remembering her geography. “The Nile is in Egypt.”

Just as though he read her thoughts, Sheshà again broke silence.

“Do you wonder that we worshipped the river in those far-off days?” he asked, dreamily.

“Did you? Why?” Rachel gazed at him curiously.

“It was, and is, the life-giver,” returned Sheshà. “But for that river, there would never have been any food in this land. And therefore no cities, no temples, no pyramids, no great schools of learning as there were here in ancient days when Moses was ‘learnèd in all the wisdom of the Egyptians.’”

“Yes, but how could the river make the corn grow, and give you food?” asked Rachel. “I thought it was the rain that made things grow.”

“In Egypt rain does not fall. But the river, this wondrous river of ours, does the work of rain. Once every year it overflows its banks, and the thirsty land is watered, and what would otherwise be all desert, like the yellow sand you see that is not reached by the flood, becomes green with waving corn, and shady palm trees, and beautiful with fruit and flowers. Yes, no wonder we worshipped our river.”

Rachel would like to have asked him how the river was worshipped, but Sheshà seemed rather to be talking to himself than to her, and there was such a curious far-away look on his face that she felt shy of questioning him. He stood gazing at the Pyramid as though he saw things even more amazing than its mighty form.

“It must have taken a long time to build,” she ventured at last, rather timidly.

Sheshà started.

“I was dreaming,” he said. “A long time to build? Verily. Would you care to see by whom, and at what cost it was raised? I can show you. We have but to travel a little further back into the Past for that. Shut fast your eyes and bow seven times as before.”

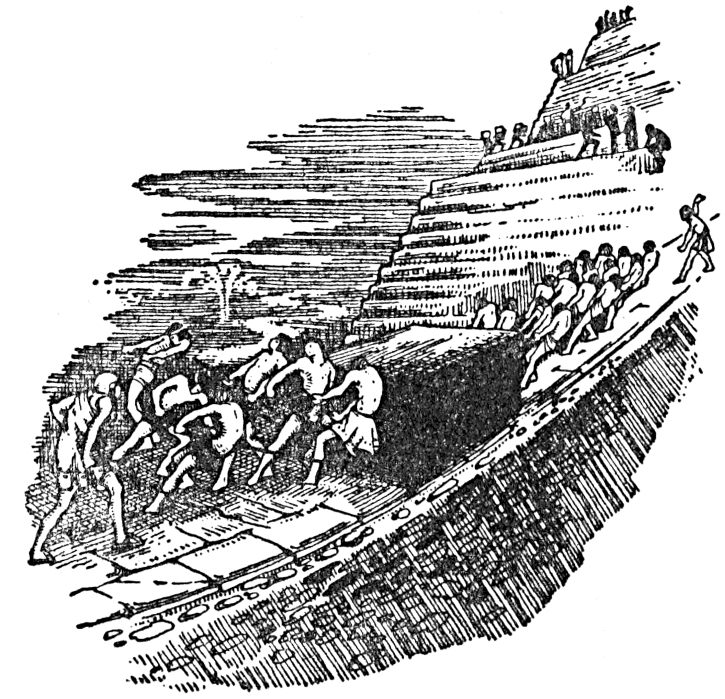

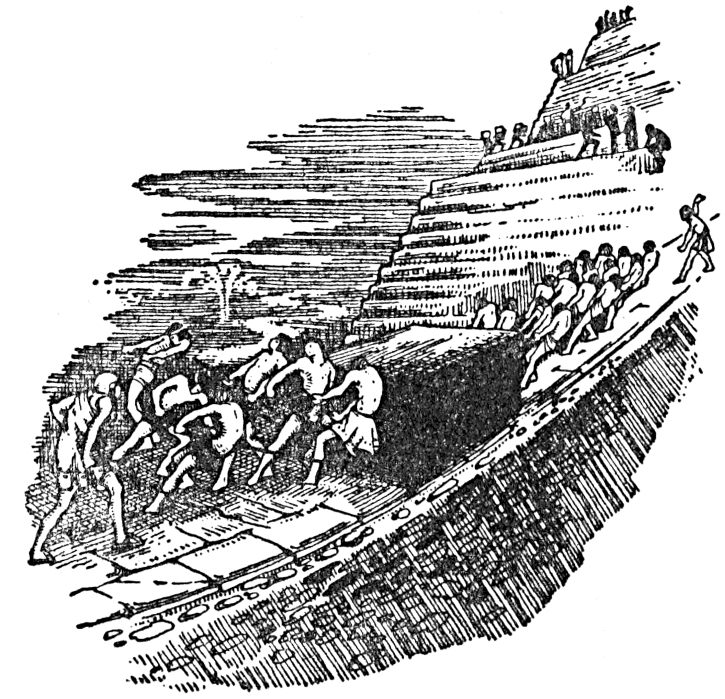

Rachel needed no second bidding, and in a few seconds, having obeyed the instructions of her companion, she looked again upon a scene strange and marvellous. The great Pyramid was there as before, but as yet not quite finished. Its mighty walls were built, and were being covered by the smooth case of granite, and round the great pile, like ants swarming over an ant hill, were the builders—thousands upon thousands of dark-skinned, almost naked, men, toiling like the slaves they were. Here great blocks of marble and granite were being dragged from barges on the river. There, hundreds of slaves were hoisting the huge slabs into place on the as yet, unfinished walls, while multitudes of others swarmed over and round the monument, cutting, hammering, polishing, chiselling. A hum as of innumerable bees filled the air, and indeed, Rachel was reminded of a hive, the inside of which her father had once shown her, all quivering with the movement of the worker bees as they toiled to make their cells.

She gave a little scream of astonishment at the sight of the thronging multitudes, and presently heard the grave voice of Sheshà speaking.

“Behold, little maiden, in what manner this Wonder of the World was fashioned. Out of the toil and labour of flesh and blood, in the days when the Pharaohs ruled in this land, and cared naught for the lives of their humbler subjects. Of these, as you see, they made slaves who did the work that in the world of to-day is performed by machines, by steam power, by electricity, by all the new inventions of modern times.”

“Do the people who come to Egypt now know all this? I mean people who don’t come in a magic way like me. Are there history books all about Egypt as it was long ago?”

Sheshà pointed to the Pyramids. “That and many other monuments are the history books—the great tombs, and all the palaces and temples and columns still standing after thousands of years. On them are written the story of the land. Behold, it is being written before your eyes, since by what you call magic you are watching the work of men who laboured four thousand years before Christ.”

“But how can those funny pictures and signs they are cutting be writing?” asked Rachel, watching a man who was graving strange marks on the granite blocks.

“Such was the writing of the ancient Egyptians,” replied Sheshà, “called in later days hieroglyphics, or secret writing, because, as ages passed, the meaning of the writing was forgotten, and men gazed at these strange signs and wondered what they meant, and what secrets were hidden from them by a language which no one could read.”

“And did they ever find out the secret?” asked Rachel, eagerly. “Can anyone nowadays read what is written on stones like these?”

“Yes. The secret has at last been discovered. For thousands of years it was hidden, but at last, in modern days, almost within the life-time of some old men and women still on this earth, the mystery was revealed by means of a magic stone.”

“I know!” cried Rachel excitedly. “That was the piece of marble I was looking at when I met you in the British Museum—was it a minute ago, or ages?” she went on, looking puzzled. “It all seems like a dream, somehow. But I remember Miss Moore, saying ‘This is the Rosetta Stone’—and I didn’t know what she meant. And then you said, ‘That stone is a gate into the Past,’ and I didn’t know what you meant, either!”

Again Sheshà smiled gravely as he looked down at her.

“I will tell you. Ninety years ago, a Frenchman was living in this mysterious land of Egypt; knowing no more of the secret writing on palaces and tombs and temples than do you, little maiden. But while he was at Rosetta, which is a town on the sea coast not far from where we stand, he found a broken block of marble—a fragment from what was once, perhaps, a mighty temple. Upon it he saw the secret marks he could not understand, but beneath it were some lines in Greek, which he and other people could read. Now, thought the Frenchman, ‘What if these Greek words should be the translation of those hieroglyphics above, which no one for thousands of years has been able to decipher?’ So he brought the broken stone away with him. And the scholars examined it, and at last, after patient study, comparing the Greek words, which they could understand, with the mysterious signs and pictures above, they learnt to read them also. And so, from that piece of black marble which now rests in the great museum of your great city of London, learned men have made Egypt give up one of its many secrets. All that is written on columns, walls and tombs, can now be read by the scholars who have studied the hieroglyphic writing of this ancient land, and translated it into English and French, and all the languages of men who live to-day. Was I not right to call ‘the Rosetta Stone’ a stone of magic, a gateway into the Past?”

PHARAOH IN HIS CHARIOT

“Oh, yes!” exclaimed Rachel, drawing a long breath. “If that Rosetta Stone had never been found, people would still be looking at the—what did you call the writing? Oh yes, the hieroglyphics, and wondering what they mean, wouldn’t they? But you know, of course? You have always known.”

“I wrote signs and figures like these, six thousand years ago,” replied Sheshà, gazing upon the mighty unfinished Pyramid upon which, like clustering bees, the brown-skinned, half-naked men were slaving.

“Will you read me something that’s written there? Please read what that man has just finished carving,” begged Rachel, pointing to a youth who was working at the base of the Pyramid. “What do those signs mean?”

“They record,” said Sheshà, glancing at them, “that a hundred thousand men were always kept working upon this tomb. These slaves that you behold are the last hundred thousand, for as you see the Pyramid is nearly built. But for twenty years previous to this moment of Past time, every day, a hundred thousand men have been working in the same way as these poor slaves before your eyes.”

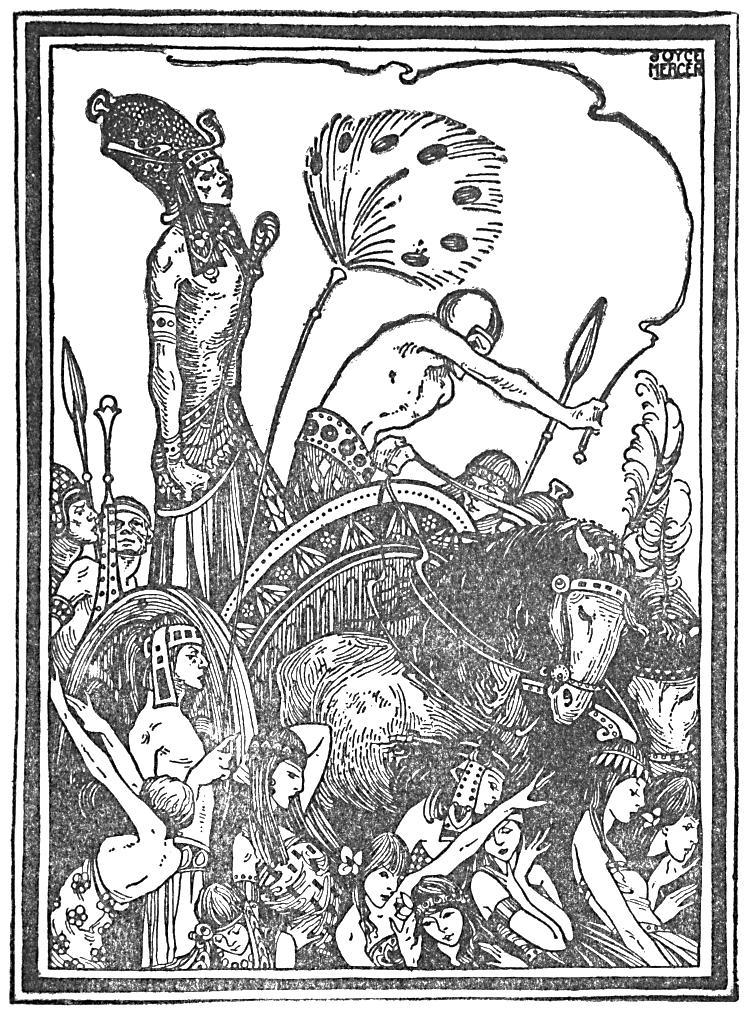

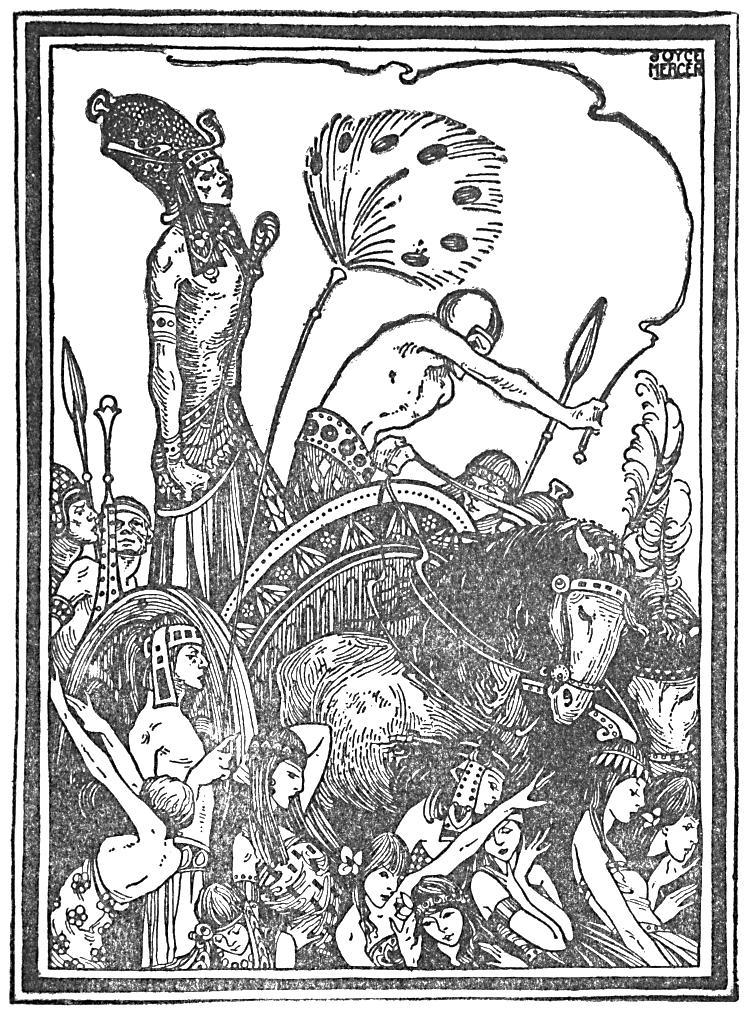

Rachel was just trying to put into words something of all the wonder and bewilderment she felt, when a strain of music that sounded rather faint and far away made her turn quickly. The sight she saw was so wonderful that I scarcely know how to describe it.

“Who is this?” she whispered. “Why are the people bowing down before him?”

“It is Pharaoh the king, come to look at his Pyramid—the tomb for himself which is rising under the hands of his slaves. Well may you gaze in wonder, O child, for never before this, has a little English maid been given sight of the far, far Past. You behold Pharaoh in all his pomp and glory as he lived six thousand years ago.”

And indeed Rachel gazed in wonder.

Looking down from the raised platform of soil on which stood the nearly finished Pyramid, she saw a broad road, thronged with a glittering company. In their midst, standing upright in a chariot painted with brilliant colours and enriched with gold, was the imposing figure of a man with an olive-tinted skin, dressed in a white robe, bordered with gold. A head-dress strangely shaped almost shrouded his face, and on his bare brown arms were bracelets, and hanging from his neck long chains of metal work.

Running beside and behind the chariot, were slaves carrying great fans, made, some of palm leaves, some of feathers. They were followed by a crowd of girls in gauzy robes, whose black hair fell in tight ringlets on their bare shoulders, holding in their hands musical instruments of curious form. Behind them followed other chariots filled with men clad in the same sort of dress as that worn by Sheshà.

Rachel saw the wonderful procession clearly enough, yet it seemed as though she was looking at it through a slight mist which quivered like hot air, and made the figures behind it a little unreal, as if something in a dream. This gauze-like mist she had noticed before, in gazing at the workers on the Pyramid. It stretched between her and the slaves like a barrier behind which, though she could watch them, they toiled out of touch, and somehow a long way from her.

“You are beholding scenes that took place thousands of years ago, remember,” said the voice of Sheshà, and though Rachel had not spoken, she knew he read her thoughts, and was explaining. “Ages ago all these people were turned to dust. They have arisen before your eyes—but only like painted figures real though they seem. If you tried to touch them your hand would but meet the air.”

“What is he going to do? Where is he going?” whispered Rachel, who was feeling awe-struck, and perhaps a little frightened.

“Pharaoh is going to look at the tomb which has been prepared for him,” said Sheshà, gravely. “In a moment we will follow him into the heart of the Pyramid.”

“Pharaoh comes into the Bible,” began Rachel, looking puzzled. “But I thought you said it was another man, King Cheops, who had this Pyramid built.”

“Pharaoh was the name given to all the kings of Egypt, but this is not the Pharaoh who dreamt of the fat and lean kine, nor the Pharaoh Moses knew, who was stricken with plagues. This Pharaoh, whose other name was King Cheops, lived long before the days of Joseph and Moses.”

Rachel gave a funny little murmur of excitement.

“We have gone back far into the Past, haven’t we? It’s—it’s rather frightening. I feel as though I should never get home again!” She looked really anxious, and Sheshà laid his brown hand gently upon her head.

“Have no fear. In less time than I take to say it, you will be seated in an omnibus, travelling back to your aunt’s home,” he declared with a curious smile.

“Oh, but I don’t want to go yet!” Rachel hastily assured him. “I want to see everything. It’s so frightfully interesting,” she went on, incoherently.

“Again have no fear. You shall see and hear, for Time itself is a ‘magic’ thing, little maiden, and wonders can be worked during the opening and shutting of the eyes. Let us now follow that procession to the royal tomb.”

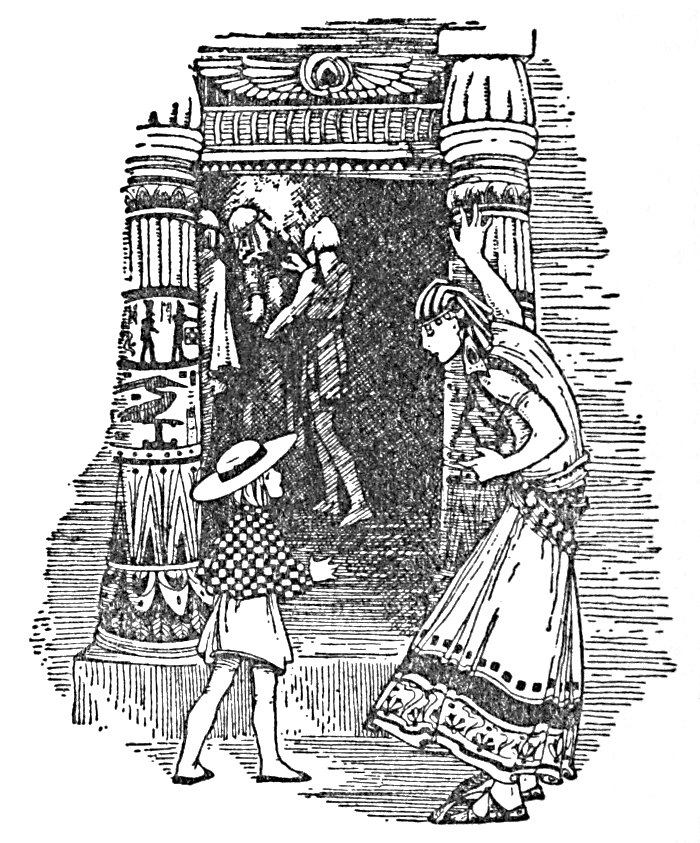

The painted chariot drawn by white horses with marvellous trappings, had now been reined up before the entrance to a passage on one side of the Pyramid. On either hand the workmen and the other people who had been passing to and fro now lay prostrate in the dust, while the great king was led from the chariot by the men Rachel had already seen dressed in robes like that worn by Sheshà.

“Those are the priests of the order to which I belong,” he said. “They are the people nearest to Pharaoh, the learned men whom he honours—poets, historians, physicians, as well as priests. With them he talks and takes counsel. These others,” he pointed to the poor men on the ground, “are his slaves who bow down before him, and are used as beasts of burden.”

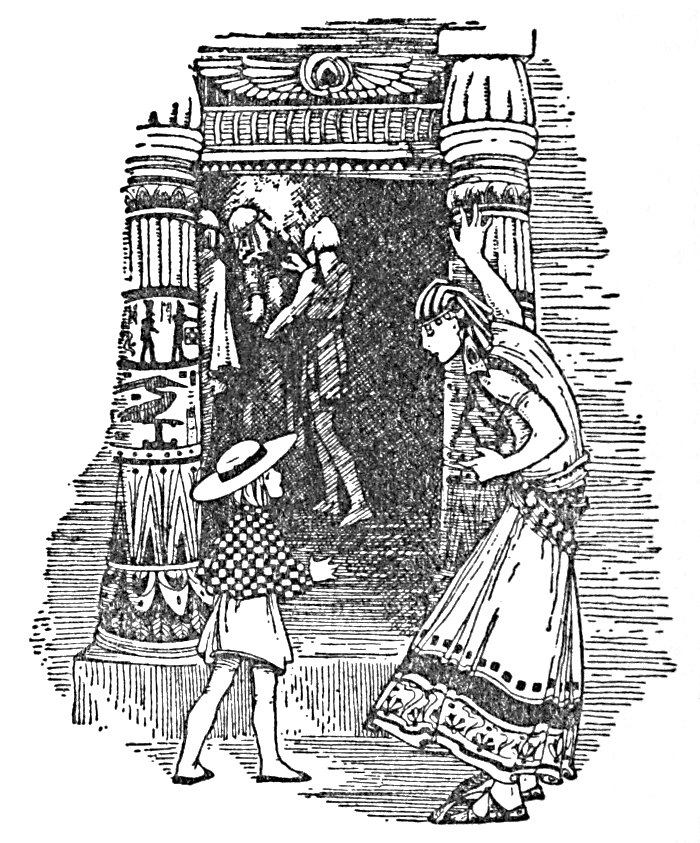

Rachel looked at them pityingly as with Sheshà she followed the wise men and the reigning Pharaoh, King Cheops, into the passage hewn within the Pyramid. No one noticed her presence, and somehow, though she was almost close enough to touch the robes in front of her, Rachel was not surprised. Plainly, as through the quivering haze surrounding them she could see the wonderful group of people, she knew they were not exactly real. She could not have touched them. She saw their lips move, but she heard no sound.

In a few minutes the passage, which sloped upwards, broadened out into a little hall lined with polished granite. Here the priests who were following the mighty Pharaoh, very slowly and solemnly ranged themselves against the walls, leaving the middle of the floor clear. Rachel then saw the king standing alone, and looking down upon something that looked like a coffin made of red granite placed in the centre of the hall. The priests bowed their heads, and she saw their lips moving, while the king stood motionless as a statue, his white robes and his strange head-dress appearing as though they were carved upon a painted figure.

For a second Rachel saw this, and then almost before she could breathe, she was standing under the blue sky, looking at the scarcely finished outside of the Pyramid, from which all the builders had disappeared, as had also the crowds upon the road bordering the river Nile.

She rubbed her eyes. “It’s so strange,” she began, dreamily. “Was all that great Pyramid built only to hold a little grave? Because I suppose that was what the stone thing that the king looked down on, really was?”

“It was the outside case of a coffin—yes,” said Sheshà. “Such a case is called a sarcophagus. The real coffin was made of wood, placed within the sarcophagus, upon which a granite lid was fixed and sealed down when a man was dead.”

“Why did this Pharaoh want such a great place only for a tomb?” asked Rachel, still puzzled. “Fancy making thousands and thousands of people work, just to build a great heap over a grave! Why did he do it?”

“Partly because he wanted to be remembered for ever (and though he was forgotten for ages, we are now talking about him after six thousand years!) But also because of what was taught by the ancient religion of the Egyptians.”

“What was that?” asked Rachel.

Sheshà smiled, his grave, strange smile. “It taught many things difficult to explain to a little maid of to-day. But one thing was this. When a man died, his soul left his body, and wandered about, entering into other bodies—possibly for hundreds of years. But it might happen that, after many ages, the soul should want to return to its old home—its old body. Therefore, that body was carefully preserved, in case the soul should wish to re-enter it.”

“But if it was very long before it wanted to come back it would find its home turned to dust, wouldn’t it?”

“For that we provided,” answered Sheshà, “by preserving the poor body in a way that is called embalming. We filled it with sweet spices, and wrapped it closely in linen bandages, and——”

“I know! The dead people like that are called mummies, aren’t they? I was just going to ask Miss Moore to take me to see them when I met you!” Rachel interrupted.

“There are many such embalmed bodies in your great museum. When you see them, little maid, remember that you are looking upon the very features of men and women who lived under this blue sky, and enjoyed this sunshine, thousands of years before their bodies were taken to your grey city beside the Thames. They were people who worshipped indeed, but gods very different from the God worshipped in your churches and cathedrals of to-day.?