SECOND WONDER

THE HANGING GARDENS OF BABYLON

All the rest of that day Rachel went about feeling excited and happy. It was not till next morning when she woke that doubt crept into her mind. Could she really have been to Egypt and seen the great Pyramid of Cheops before it was quite finished? Surely, she couldn’t really have talked to Sheshà, the priest of that ancient king! It must, of course, have been a dream. Yet how had she managed to go to sleep in the British Museum? And how was it, if she had dreamt the whole adventure, that she remembered everything distinctly, and not in the confused fashion of an ordinary dream? Rachel was puzzled, but she was obliged to come to the sad conclusion that somehow or other the glowing pictures in her mind, of slaves, of Pharaoh in his chariot, of the room within the Pyramid holding the sarcophagus, were, as her old nurse used to say, “all imagination.”

It was a terribly disappointing thought, and for the whole of the following day she felt quite dull and miserable, especially as Aunt Hester wouldn’t hear of another immediate visit to the British Museum.

“It’s too far,” she declared. “You may go next week. But I can’t think why you’re so anxious about it. Miss Moore says you didn’t seem particularly interested while you were there.”

Rachel couldn’t of course tell Aunt Hester that in her longing for the British Museum, there was a faint hope that if by any chance the adventure had been “real”—there, if anywhere, “something might happen.”

A few mornings afterwards, however, something did happen. At breakfast time Aunt Hester put down a letter she had been reading, and looked across at her niece.

“Old Mr. Sheston is coming to lunch,” she remarked. “He says he thinks he must have seen you the other day. He knew you from your likeness to your father.”

“Who is old Mr. Sheston?” asked Rachel, looking up from putting more sugar on her porridge.

Aunt Hester smiled. “He’s a funny old man who has been a friend of our family for years, and knew your father as a boy. He is doing some important work at the British Museum, so you’ll be able to talk to him about it.”

Rachel pricked up her ears.

“Why is he funny?” she enquired.

Again Aunt Hester smiled. “He dresses in a strange way for one thing, and he has all sorts of curious ideas that you wouldn’t understand. He’s a dear old man—but eccentric. Certainly eccentric,” she added as though to herself.

“Eccentric means not like other people, doesn’t it?” murmured Rachel. “I’ve never heard Dad talk about him.”

“I don’t think he’s seen him since he was a boy.... Certainly you are very like your father as he was at your age, child! I’m not surprised that the old man recognized you.”

Rachel was running across the hall just before lunch, when in answer to a knock at the front door, the parlourmaid admitted a strange figure, wrapped in a long cloak, one end of which was thrown over the left shoulder. A battered hat almost hid the face of the little old gentleman who entered—but in a flash Rachel remembered him. He was looking at the Rosetta Stone the day she and Miss Moore went to the British Museum! And he had spoken to her—or had she dreamt this? It was curious, but she really couldn’t remember. All she knew at the moment was, that he and the Rosetta Stone were, as she put it, “mixed up together in her mind.”

By this time the visitor had taken off his hat, and Rachel, so puzzled and curious that she had stopped short in the middle of the hall, saw a pair of dark eyes in a crinkled, wrinkled face under a fringe of white hair.

The old man smiled and held out both hands.

“You are Rachel,” he said. “I knew when I saw you last week in the Egyptian gallery, that you must be your father’s daughter.”

Rachel felt suddenly shy, and was glad when Aunt Hester came down the stairs and, after a word or two of greeting, led the way straight into the dining-room.

At table, during the meal, Rachel sat opposite to the guest, who now and then looked across at her, and every time she met his dark eyes she was puzzled afresh.

“You’ll be glad to hear that Rachel is most interested in the British Museum,” said Aunt Hester, presently.

“I am glad to hear it,” was all the old man said, but he smiled in such a way as to make Rachel more excited and puzzled than ever.

She listened eagerly to what he was saying to Aunt Hester. He was talking about what he called the “explorations” in Egypt, and she gathered from his conversation that men were often sent out by the people who took charge of the British Museum, to dig and explore among the ruins in Egypt and other ancient countries, and to bring back some of the things they found to London.

He made the story of these explorers and what they discovered, so exciting, that Aunt Hester, who did not at first seem very curious, began to ask questions. Rachel wanted to ask a great many more, for her head was still full of her strange dream—as she now called it—about Egypt, and it was interesting to know how all the tombs and monuments and statues she had seen last week had found their way to England.

“You can run away now, Rachel,” said Aunt Hester, when lunch was over, and Grayson was bringing in coffee.

“Don’t let her run very far,” observed Mr. Sheston. “Because I’m going to take her back with me to the Museum in ten minutes.”

He said this without looking at her, and Rachel gasped for joy, and glanced imploringly at Aunt Hester, who laughed.

“You always announce what you are going to do, I remember,” she declared, speaking to her guest. “You never ask.”

“A habit of mine,” returned the old gentleman quietly. “Acquired long ago.”

“Go and get ready,” said Aunt Hester, with a nod to her niece, and Rachel flew like the wind.

Ten minutes later she was seated in a taxi-cab with Mr. Sheston, who talked about her father, about her country home, her brothers and sisters, and everything in the world except just the things Rachel wanted him to talk about—Egypt and the Pyramids.

At last, however, he said quite suddenly, just as they were going up the steps of the Museum, “How long is it since you were here?”

“Five or six days, I think, or perhaps—”

“Seven days,” corrected the old gentleman, quietly, and all at once Rachel began to get excited.

They entered the building, and she noticed that all the officials in uniform touched their hats to the little old man who was evidently very well known there. He turned at once to the Egyptian Gallery, and as they passed the Rosetta Stone, Rachel looked back.

“I know all about that,” she said, glancing up at Mr. Sheston, who only smiled.

“We will go to the Babylonian Room in a minute,” he said. “Do you know where to find Babylonia on the map?”

Only that morning, in looking as she always did now, for Egypt, Rachel had seen it marked in her atlas.

“It’s up above Arabia, isn’t it?” she began, uncertainly “Up above the Persian Gulf.”

“And do you remember any of its cities that were famous once?”

“Babylon?” suggested Rachel.

Mr. Sheston nodded.

“Babylon,” he repeated, and after a moment added, as though to himself, “How far is it to Babylon?”

“Why, that’s in a book of poetry I’ve got,” exclaimed Rachel. “It’s called ‘A Child’s Garden of Verses.’”

“Yes, there are a great many things in Stevenson’s Child’s Garden,” said the old man. “We’ll find out how far it is to Babylon presently. But, before we do that, just come into this room for a moment.”

He took her hand and led her into a narrow passage to the right of the big Egyptian hall through which they had come.

“Is there anything here that reminds you of—something else?” he asked.

Rachel glanced about, and suddenly her eyes rested on a monument against a wall, carved curiously in stone. Beneath it there was an inscription, and she went nearer and began to read the words aloud.

“The tomb of Sheshà, High Priest of Cheops,” she began, and suddenly stopped short.

“Why...!” she exclaimed, turning to Mr. Sheston, and then again stopped short, for in his place stood her friend Sheshà in his beautiful robe, his young face framed by the strange head-dress she so well remembered! And yet—somehow—it was Mr. Sheston too! Sheshà and the old man were in a curious way one and the same person!

“Why, you are Sheshà!” cried Rachel, incoherently. “But then—why?”—she glanced at the tomb—“That means you were dead—ages and ages ago?” she whispered. “How can you be here—?”

The young priest smiled. “Tombs are but folly,” he answered. “Do you remember, little maid, what I said to you of the soul, and how it lives and returns after many thousand years to inhabit the same, or perhaps another body?”

Rachel nodded, too overwhelmed to speak.

“Well, then, are not tombs folly?” he repeated, still smiling. “But come, of Egypt you have had a glimpse already. Now shall you behold Babylon.”

He turned and led the way towards another gallery running parallel with the Egyptian one, and, as Rachel followed him, she wondered for a moment why the people strolling about in the Museum did not stare in amazement at the wonderful figure of Sheshà in his priestly robe. No one took the slightest notice, however, and she remembered that Miss Moore had on a previous occasion seen and heard nothing.

“They’re not mixed up with seven, I suppose,” she reflected, before Sheshà began to speak again. He talked, she thought, rather as though he were translating from another language, trying to make what he said quite modern. “But sometimes,” thought Rachel, “he forgets—and then he says ‘behold,’ and ‘verily,’ and old-fashioned words like that!”

“Let us first look at some of the wonders which, long buried, have come at last to this Museum,” he suggested, pausing in front of a huge statue. It represented a creature with the body of a bull, and the face of a man with a long curled beard cut square—while from the shoulders of the beast sprang two great wings.

“Here is one out of many such marvels,” he added.

Rachel looked at the monster, full of curiosity.

“Was this dug up by the people you were talking about to Aunt Hester to-day? I mean—at lunch time—when you were—Mr. Sheston?”

Sheshà smiled. “I was the same person then as now. It was only my body that was different.... Yes, little maid, this was found by the explorers not far from Babylon. Now glance with me at these pictures in stone.” He turned into a narrow gallery close at hand, and pointed to the walls against which were fastened large slabs of stone sculptured most beautifully with scenes of hunting, with processions in which kings rode in chariots under graceful canopies like parasols hung with fringe, or stood looking down upon long lines of prisoners chained together.

“These came from the palace of one Tiglath Pileser, a king who lived more than seven hundred years before Christ was born. He was one of the conquerors of Babylon.”

“But I do want to see Babylon itself!” exclaimed Rachel. “You did mean I should really see it, didn’t you?”

“Patience!” murmured Sheshà. “Patience! You are just about to see Babylon first as it is now—and then as it was in the days of its splendour. Shut your eyes. Beat seven times with your foot on this stone floor—and have no fear of what befalls. You are safe with me.”

Trembling with excitement, Rachel did as she was told, and at the last tap of her foot, was conscious of a most strange and wonderful sensation. She seemed to be out of doors, and not only out of doors, but rushing through the air, while a noise like that of a great engine almost deafened her.

“We are near Babylon!” said a voice close to her ear, and, as she opened her eyes, Rachel gasped, for she was seated in an aeroplane, and the pilot of the machine, in the dress of an airman, was—Sheshà! Rachel had so often longed to fly, that at first she could think of nothing but the wonder and excitement of her first rush through the air, and it was only by degrees that she began to notice the earth below. The machine was dropping nearer to it now, and she saw they were flying over a vast plain through which flowed a river. Three large mounds near this river broke the monotony of the desert place, overarched by the beautiful blue sky, and when the aeroplane skimmed yet lower, Rachel saw little figures moving near the mounds, like ants running over an ant heap.

At the same moment the noise of the aeroplane’s engine ceased, and she was able to talk to the pilot.

“Why those are men, aren’t they?” she said, pointing to the tiny figures. “And what are those heaps of rubbish there?”

“All that is left of Babylon—the beautiful and proud City of Babylon,” answered the voice of the pilot, Sheshà.

Rachel looked at the desert plain with its three “rubbish heaps,” as she called them, in silent astonishment.

“Is that where the bulls with wings and the other things in the British Museum come from?” she added at length.

“Some of them—yes.”

“And are those little men down there digging up other things now?”

“Yes. They are working for the Museum. By-and-by, in a few weeks, perhaps, you may read a column in your newspaper at breakfast time giving an account of the latest things found in that heap,” he pointed to the largest of them. “That mound below you is called Babil, and it covers the palace in which dwelt King Nebuchadnezzar, nearly three thousand years ago.”

“The Nebuchadnezzar in the Bible that I was reading about with Miss Moore only this morning?”

“Yes—the Nebuchadnezzar who conquered the city of Jerusalem and brought the Children of Israel captives to Babylon—the Nebuchadnezzar who set up the golden image to which Daniel would not bow down.”

“And the fiery furnace!” interrupted Rachel, eagerly, “that didn’t burn the three Children of Israel when Nebuchadnezzar threw them into it.... I remember!... And there’s a psalm about them when they were prisoners in Babylon.”

“By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept when we remembered Zion,” quoted Sheshà, in a dreamy voice. “There is one of the rivers of Babylon.” He pointed to the great stream—the Euphrates—on both sides of which the city was built.

“It doesn’t look as though there could ever have been a city here,” Rachel declared, gazing down upon the desert and the mounds of earth. “How could it have disappeared altogether like that?”

“Thousands of years have passed since it was standing. It has been burnt to the ground many times, and laid in ruins. The sand of the desert has swept over it, and new races of men have arisen, knowing nothing of its ancient grandeur. It is only sixty years ago that scholars from France and Germany and England began to explore those heaps of rubbish which cover its palaces and temple.”

“Oh, I do want to see them!” exclaimed Rachel. “I mean as they used to look when Nebuchadnezzar was king. Not just the bits of them that people dig up now!”

“We will make a landing,” said Sheshà in a matter-of-fact voice, and in a few moments the aeroplane had touched the ground, and he was helping her to jump out of the marvellous machine, which, surrounded as she was by so many other marvels, Rachel took almost as though she had been used to an aeroplane all her life.

“You behold Babylon as it looks to-day,” went on Sheshà, stretching out his hand towards the ruins. “In a second you shall behold it as it looked three thousand years ago when Nebuchadnezzar was king. And your guide shall be a little maid of your own years.” Almost before he had finished speaking he laid his hand gently over Rachel’s eyes....

“Count the magic number aloud.”

The voice that spoke certainly did not belong to Sheshà, and when full of eagerness her eyes flew open they rested first of all upon the loveliest and strangest little girl you can possibly imagine.

Her hair, black as ebony, was cut straight across her forehead, and fell in tight ringlets to her shoulders. She wore a thin gauze robe spangled with gold, and on her bare brown arms there were bracelets, and round her slim little ankles golden anklets, which tinkled as she moved.

As her great dark eyes met Rachel’s blue ones she said gravely:

“I am Salome, handmaid to the Queen of this city of Babylon. Come with me and you shall see all its riches and its glory. Sheshà has commanded it.”

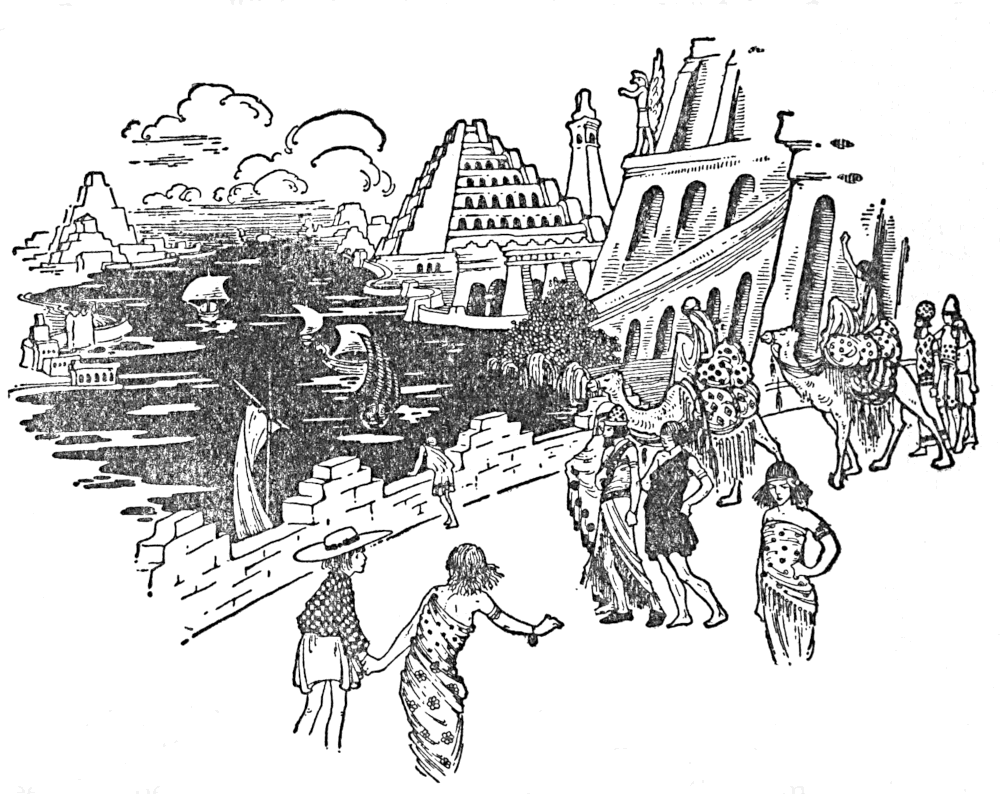

Rachel was too bewildered to wonder how it happened that she understood the child, who was certainly not talking English. But, strange language though it was, she seemed to know it as well as her native tongue. There were besides, other and even stranger things to amaze her, for before her, under the burning blue sky, was spread a gorgeous city, or rather what looked like miles and miles of gardens and palaces and temples, enclosed within huge walls.

From the slightly raised ground on which Rachel with her new companion were standing, she could see these city walls—a double row of them—stretching away to form a gigantic square enclosing the river, the woods and gardens, and all the strange buildings which made up the city.

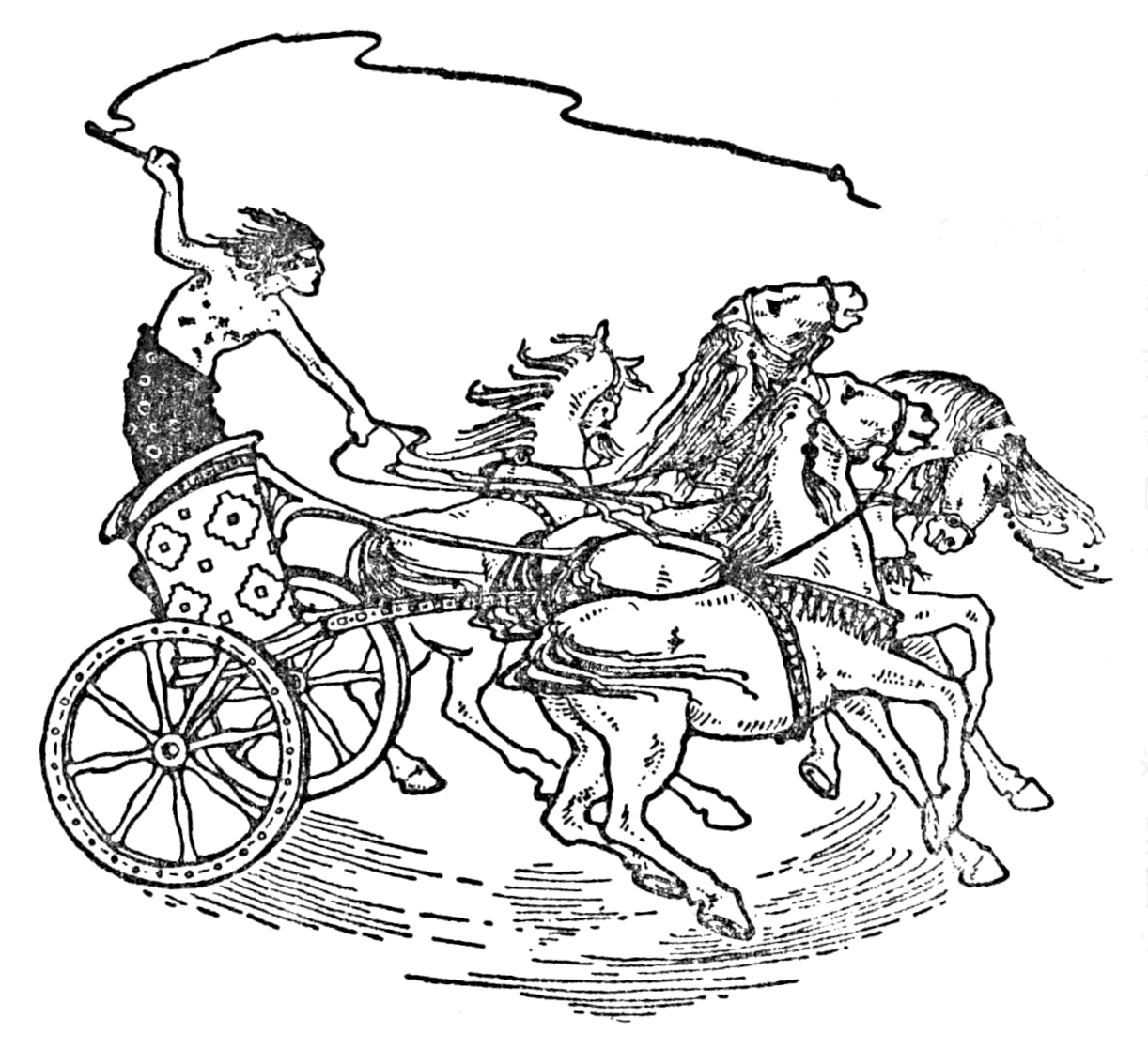

“Oh look! look!” she cried suddenly, as all at once, actually on the top of one of the inner walls, she saw a brilliantly painted chariot drawn by four horses, coming at a furious pace towards her. It was driven by a long-haired man who stood upright within the car, urging on his steeds—till he came so near the end of the wall that Rachel held her breath, expecting to see chariot, horses and driver dashed to the ground. But, before she could cry out, the man, with marvellous skill, turned horses and chariot, and drove at full speed back again along the wide top of the wall.

“Just think of a wall broad enough for four horses to gallop along—and turn!” Rachel almost screamed the words in her excitement.

“That is Akurgal, the driver of the king’s chariot,” said the little Babylonian girl, unconcernedly. “He drives like the wind for fury when it pleases him.”

Rachel scarcely knew in which direction to look first, so glorious was the view. She saw that each of the four sides of the wall was pierced by gigantic gates made of bronze—all the gates opening upon broad streets which crossed one another, so that the whole city was divided into squares, filled with gardens and houses. The broad river flowed through it from north to south, and over the river hung a mighty bridge, at each end of which was a palace.

It was difficult for Rachel to make up her mind in which direction to turn her eyes, but the sight of something that appeared like a forest-covered mountain rising near one of the palaces, was so lovely that she pointed to it and turned to Salome.

“What a beautiful mountain!” she exclaimed. “How funny there should be only one—because the rest of the country is so flat. There isn’t another hill as far as ever I can see,” she added, glancing over the wide plain in which the city lay.

Salome smiled.

“That is no mountain,” she said. “It was made by human hands. It is the great glory of our city, and, so my mistress says, in time to come, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon will be called one of the Wonders of the World.”

Rachel started. “There are seven Wonders of the World,” she began, eagerly. “I’ve seen one of them already—the Great Pyramid, you know. And now——”

“I have heard of the Pyramid in the land of Egypt,” Salome interrupted. “But come now and see more closely our wonder—the Garden that is like no other in the world.”

She took Rachel’s hand, and in a few moments they had entered the city through a gate which Rachel noticed was covered with tiles of blue enamel as brilliant as the sky above them. And on either side of the gate, like sentinels, stood huge winged bulls carved in stone. But how different they looked here, she thought, in the golden sunshine, with the wonderful blue tiles behind them, and their great shadows, black as ink, stretching on either hand!

“This is one of the new gates built by our king,” Salome told her. “He has caused inscriptions to be written about them so that all the world may know what adornments he has added to our fair city of Babylon. Our city that shall last for ever,” she added proudly.

Rachel glanced at her, and thought of a great rubbish heap she had recently seen—“the mound called Babil which covers the palace in which dwelt King Nebuchadnezzar nearly three thousand years ago”—she remembered the very words of Sheshà.... How amazing it was to be walking with this little girl in the very city that now lay under a mound of earth! To be talking to a little girl who lived nearly three thousand years ago, and had no idea that her home was even now being dug up in fragments by men living in the world to-day!... For a moment it all seemed too puzzling to be true. Rachel rubbed her eyes with her disengaged hand, and half expected the whole vision to disappear. Yet when she looked again, the lovely scene still lay before her, and she could feel the warmth of Salome’s little brown hand within her own.

“I must be getting used to the Past,” she reflected. “Because now I can feel as well as see the people. They didn’t seem quite real when I was with Sheshà in Egypt. But now it’s different. Is it because these people didn’t live quite so far back into the Past as King Cheops and his slaves, I wonder?”

She glanced again at the grave, strangely clad little girl at her side, who talked as though she were quite grown up.

“I mustn’t say anything about the rubbish mound, or tell her anything about the sort of world I belong to,” she reflected hurriedly. “She wouldn’t understand. I suppose she thinks I’m living in her times, but have just never happened to see Babylon before. And that’s quite true!” she added to herself, with a little inward chuckle.

While such thoughts as these were hurrying through her mind, she was looking right and left, full of eager curiosity, for the bridge she was crossing was thronged with amazing figures.

Men with black, curling beards, bare-legged, and bare-armed, wearing tunics of brilliant colours, passed her. Some of these were seated upon the backs of camels following one another in long lines. The soft-footed, grey beasts were loaded with merchandise, and the bales on either side of their humped backs swayed as they moved. They were decked fantastically with trappings of plaited scarlet wool, hung with tassels of brilliant colour. After such a procession of camels and their drivers, would come perhaps a chariot with four horses abreast, driven by a fierce-looking man in a gorgeous fringed robe, whose dark eyes flashed like jewels in his bronzed face. Following one such chariot, she saw a group of girls in gauzy tunics, bracelets on their arms, tinkling anklets above their feet, dancing as they came, and singing a wild song as they tossed their arms above their heads.

“They are going to the Temple of Belus,” explained Salome, as Rachel stood still to look at them.

She turned round and pointed with her little brown forefinger to a great building at the other end of the bridge.

“Later, if there is still time, you shall see the temple of the great God. But let us hasten now towards the gardens, for there, in the cool of the day, the queen walks with her maidens, and I must be in attendance.”

Rachel was torn between her longing to be actually within the wonderful Hanging Garden and her desire to linger on the bridge which afforded such a magnificent view. She gazed with delight upon the broad shining river which divided the city, and upon the ships with gracefully curved sails which, rowed by almost naked slaves, moved to and fro over its surface.

Some of these ships were drawn up against the quays which lined the river, as far as eye could reach, and Rachel saw a swarming multitude of men staggering under corded chests of wood which the ships had brought to be unloaded.

Salome stopped to watch the slaves at their work.

“That is merchandise for the palace, I trust,” she observed. “We have awaited it too long, and the queen grows angry.”

“What sort of things are in those boxes?” Rachel asked.

“Ivory and ebony for the thrones, and for the couches and the chariots, emeralds and fine linen, and coral and agate. Spices from Arabia and precious stones and gold,” answered Salome, in a sort of chanting voice.

Rachel gasped. It sounded like a fairy tale. Yet she remembered something like it—Where was it? In the Bible, surely!

Just as the thought of the Bible crossed her mind, a group of men passed close to her. They were dressed rather differently from the other people around her, their faces, too, looked different, and their eyes were very sad.

“Who are those men?” she enquired, looking back over her shoulder. “They look so unhappy—and homesick, somehow.” Rachel knew what it was to be homesick!

Salome glanced at them carelessly. “They are Hebrews who call themselves the Children of Israel. Our king, the great Nebuchadnezzar—may he live for ever—conquered their country and took their treasures from Jerusalem, their chief city, and brought many of them here to Babylon to live. They hate us, and we despise them.”

Rachel started as the words of the psalm darted into her mind. “By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down.... We hanged our harps upon the willows....” She had heard this sung in church, and it had meant nothing to her but just “a psalm.” Yet, here before her very eyes now, was one of “the rivers.” There were “the willows” fringing streams which flowed through the innumerable gardens, and she had just met some of the captive Jews! Rachel gasped again as all these things became “real” to her—something that had actually happened—was, in fact, happening before her eyes.

“It’s awful to be homesick,” she murmured, rather to herself than to Salome, who, without replying, ran on in front of her to a flight of steps at the end of the bridge.

“This is one of the entrances to the Hanging Garden,” she explained, looking back. “We must hasten, lest my mistress calls for me.”

Rachel followed her from terrace to terrace, too overwhelmed with delight at the glimpses of beauty she caught right and left to say a word. She saw that the whole garden was supported, tier above tier, by gigantic arches, and Salome told her each terrace was made of plates of lead, holding earth so deep that great forest trees could grow in it. If she had not known this, the whole place would have seemed to Rachel as though blossoming by magic in the heart of a forest growing in mid-air. She could scarcely believe it was not the work of some magician.

By the time they reached the uppermost terrace, on a level with the city wall, she was not only breathless, but struck dumb by the beauty and wonder of everything round her.

Mighty cedar trees spread their layers of branches between her and the burning blue sky. The air was perfumed with the scent from groves of lemon trees. Fountains tossed their sparkling drops high into the sunshine. Red roses swept in cascades from her feet down the slope to the terraces below. Along paths paved with tiles of sapphire-blue enamel, peacocks walked delicately with outspread tails, and far below, within its four-square walls, the city of Babylon lay glittering in such brilliant sunshine as in her own country she had never dreamt of, nor faintly imagined.

And now, before she had time to recover from her amazement, a new sight was presented, for, coming slowly in her direction, but as yet in the distance, a group of people approached. In the midst of them, as the little procession drew nearer, Rachel saw a lovely woman leaning back in a litter slung between ivory poles and borne by four slaves. The litter was covered with silk hangings of a rich purple, and a fringed canopy of the same material supported on poles also of ivory, was held above the swinging couch by four dark-skinned girls.

“The Queen Amytis,” whispered Salome, and Rachel drew back in sudden fright. “She will wonder who I am—and I shan’t know what to say,” she began, hurriedly. “I don’t know how to talk to queens.”

“Have no fear, she will not see you. No one here sees you but me. That is the work of Sheshà, who is greatest of all magicians and has entrusted you to me, why I know not—nor do I know with any certainty who you are. But he has commanded me to be your guide here in Babylon. No one sees, no one hears you but I alone.”

Wondering greatly, but feeling much relieved, Rachel watched the slaves as very carefully they set down the litter close to a throne-like seat, covered with silken pi