FOURTH WONDER

THE TEMPLE OF DIANA

Lessons always began for Rachel with a chapter in the Bible which she read to Miss Moore. She was allowed to choose her own chapter, and one morning, as she opened her Bible at random, the word Ephesus struck her. She wondered why this name immediately reminded her of Mr. Sheston and the story of Rhodes, for at first they seemed to have nothing to do with one another. Then she remembered that on the map—(why it was actually seven days ago since he had shown her that map)—she had seen the town Ephesus marked on the coast of Asia Minor.

“Shall I read this? It’s the nineteenth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles,” she asked suddenly, addressing her governess.

“Very well,” agreed Miss Moore.

So Rachel began to read how St. Paul, having come to Ephesus to preach Christianity, had roused the anger of a certain silversmith, Demetrius by name, who “made silver shrines for Diana.” This man, as it appeared from the story, was greatly afraid of losing his trade, because so many people were becoming Christians that no one, he thought, would care any more for the silver shrines. He therefore tried to stir up the citizens against St. Paul and his teaching, by calling together a great crowd of people, to whom he declared that all the silversmiths and workmen would suffer through this new religion of Christianity. “So that not only this our craft is in danger to be set at naught,” he said, “but also that the temple of the great goddess Diana should be despised, and her magnificence should be destroyed, whom all Asia and the world worshippeth.”

Rachel read this with interest, for she had actually seen some of the temples built thousands of years ago, in honour of certain gods, and she guessed that the temple for a goddess, “whom all Asia and the world worshippeth” must have been particularly magnificent. She went on to the next verse, which showed that Demetrius had succeeded in rousing the people to defend their old worship: “And when they heard these sayings, they were full of wrath, and cried out, saying, ‘Great is Diana of the Ephesians.’ And the whole city was filled with confusion ... some therefore cried one thing and some another: for the assembly was confused, and the more part knew not wherefore they were come together.”

Then the story went on to relate how a man called Alexander tried to speak to the clamouring people, and could not make himself heard for the noise, for “all with one voice about the space of two hours cried out ‘Great is Diana of the Ephesians.’”

Thanks to Mr. Sheston’s story of Rhodes, and thanks also to her own strange magical journeys, Rachel had some sort of picture in her mind of the scene described in the Bible.

Ephesus was not so very far from Rhodes, and it was on the coast. There must then, have been a deep blue sky above that temple round which the people shouted “Great is Diana of the Ephesians,” and dazzling sunshine, and a glimpse of wonderful blue sea!

Before Rachel had finished the chapter she had made up her mind to ask Mr. Sheston about Diana of the Ephesians. She liked the name very much, and it certainly sounded as though something interesting—perhaps exciting might be connected with it. Suppose it should even lead to an “adventure”? She scarcely dared to hope for this, but all the same there was a little hope at the back of her mind.

Anyhow, there was something, though of a different nature, to look forward to this very afternoon, for a little girl was coming to tea.

“She’s the daughter of an artist I happened to meet the other day,” Aunt Hester had explained at breakfast time. “He turned out to be a friend of your father’s, and, when he heard you were here, he said he would like his little girl to meet you, so I invited her to come to-day.”

“What is her name?” had been Rachel’s first question.

“I don’t know. I forgot to ask. But she’s about your age. She’s coming early, so you needn’t do any lessons this afternoon.”

This in itself was good news, and by three o’clock Rachel was looking out of the window for the expected visitor. But after all, when the bell rang she was too late to see who was admitted, because for the third or fourth time, she had moved across the room to the mantelpiece, to look at the watch which lay there.

Aunt Hester opened the door.

“Here is Diana,” she said. “I shall leave you together to amuse yourselves till tea time.”

“Oh, is your name really Diana?” exclaimed Rachel, forgetting to shake hands. “How funny!”

“Why is it funny?” enquired the little girl, not unnaturally, while Rachel swiftly looked her up and down.

She scarcely knew whether to think her very pretty, or only curious-looking. She had a mop of red hair, big eyes, more green than blue, and a little pointed face which reminded Rachel of the faces of certain elves in an illustrated fairy-tale book she possessed. Certainly she was rather like an elf altogether, light and slender, with quick darting movements.

“Why is it funny?” she repeated. And, when she laughed, Rachel was quite sure she was pretty, as well as curious.

“Only because I was reading about Diana in the Bible this morning—and I liked the name.”

“It’s the name of a goddess,” her visitor announced rather importantly.

“I know. ‘Diana of the Ephesians.’”

The little girl looked puzzled. “I don’t know anything about the—what did you say? Ephe—something? I was called Diana because my father was painting a picture of her when I was born.”

“What was it like?”

“Oh, it’s a lovely picture. She’s a girl running through a wood, and she has a bow and arrows in her hand. And she’s dressed in a short white thing—a tunic, you know, that comes to her knees. And her hair in father’s picture is red, like mine, and there’s a little moon, a tiny crescent moon, just over her forehead. And running behind her there are some other girls who are hunting with her. Father told me all about her the other day, because, you see, as I’ve got her name, I wanted to know.”

“Tell me,” Rachel urged.

“Well, the Greek people worshipped her, father said. She was the twin sister of Apollo——”

“I know about him,” interrupted Rachel eagerly. “Phœbus Apollo. He was the Sun-God.”

“Well, Diana was the moon-goddess. I suppose that’s because she was his twin sister? Sun and moon, you know. But, anyhow, she was the goddess of hunting as well. And she loved to be free and live out of doors in the woods. So do I—that’s why I’m glad my name’s Diana, like hers. And her father, Jupiter, let her be free, and gave her some girls called nymphs, to be her companions, and hunt with her in the woods and on the mountains.... I think the Greek people had awfully nice gods and goddesses, don’t you?”

“Awfully nice,” agreed Rachel. She was thinking of the little white temple to Phœbus Apollo in “Cleon’s” beautiful garden, and of the great statue at Rhodes. She glanced at Diana, who was perched like an elf on the corner of the table, swinging her feet. How splendid it would be if she could tell her—well, all sorts of things. But would she understand? Wouldn’t she laugh and say, “You’ve just made them up!” Again Rachel glanced at her visitor. She looked as though she might understand. There was something about her—But she determined to be very cautious.

“When’s your birthday?” she began suddenly.

“The seventh of May. When’s yours?”

“The seventh of June.” Rachel found herself growing excited. This was a promising beginning.

“How many brothers and sisters have you got?”

“Six.”

“Then you’re the seventh child?” Rachel held her breath now.

“Yes. And I’m the youngest.”

“So am I. And is your father the seventh child in his family?” She scarcely dared to put the question.

Diana laughed, and began counting on her fingers. “Let me see—Uncle John, Aunt Margaret.... And there was Aunt May, but she died, and then Uncle Dick.... And then.... Yes, he is. I never thought about it before. What made you think of it?” Diana seemed much amused, but Rachel was desperately serious.

“Wait a minute,” she urged, “and perhaps I’ll tell you.”

The next “minute” was occupied in putting breathless questions to Diana.

“Yes!” she exclaimed at last. “You’re just as much mixed up with sevens as I am. Oh, isn’t it perfectly wonderful that I’ve actually found someone as lucky as I am? I shall have to tell Mr. Sheston.... But perhaps he knows. I shouldn’t be a bit surprised if he had something to do with getting us to meet each other. You see he——”

But Diana’s mystified face checked Rachel in the midst of her excited chattering.

“Of course you don’t understand anything about it yet,” she exclaimed. “How stupid I am. I shall have to tell you everything from the beginning.”

So she began the story of her first visit to the Museum, of the little old man who had spoken to her there, of the mysterious seven times bowing before the Rosetta Stone, and of all the marvels that had since happened.

And as she talked, explaining and describing, she saw Diana beginning to “understand.” Her eyes grew bright with eagerness, and, when at last Rachel paused for breath, she slipped from the table and began to dance about the room in her delight and excitement.

“I knew something like that might happen if only I could find out the way to make it,” she cried. “Because, do you know, Rachel, I often have dreams that are quite real—just as real as this room, and you, and the tables and chairs are now. In those sorts of dreams I go to places I’ve never seen in my life. Funny places where everything’s quite different. People wear different clothes, and don’t talk English—and yet I understand what they say. But I’m only there for a minute before I come back again to my own bed and my own bedroom. And then I’m most awfully disappointed because I’m always quite sure that there’s a way of making the dream last, so that I can go on, and have adventures—instead of only seeing things in a sort of flash, you know.”

“Mr. Sheston can make them last—if they are dreams!” Rachel declared. “I have to call him ‘Mr. Sheston’ here,” she added. “But he’s really Sheshà and Cleon, and I expect ever so many other people as well. And yet all the same person, you understand. In this life he just happens to be Mr. Sheston, that’s all.”

“Oh, I do wish I could see him,” sighed Diana.

She had scarcely spoken before her wish was granted, for at the last word the door opened, and Mr. Sheston came in.

Rachel gave a shriek of delight, and seizing Diana’s hand, dragged her to meet him.

“This is Diana. She’s the seventh child of the seventh child, and she was born on the seventh of May, and everything that happens to her has sevens in it, and she has dreams, and—” Rachel tripped over her words in her excitement, and Mr. Sheston laughed.

“Your Aunt Hester told me to walk up,” he said in an ordinary everyday voice. “So this is Diana? How do you do, Diana?” He shook hands with her, and turned to Rachel. “I came to see whether you felt inclined for the Museum this afternoon. But as you have a friend with you—perhaps another time?”

Diana gave a little gasp, and grew very pink, but seemed too shy to speak.

But Rachel, who had seen a twinkle in Mr. Sheston’s eyes, laughed happily.

“It’s just what Diana wants more than anything. Oh, do let’s put on our things at once.”

She was running to the door when the old gentleman stopped her.

“Plenty of time. Plenty of time,” he said quietly. “Haven’t you yet learnt that ‘time’ is as ‘magic’ as most other things? What have you two been talking about?”

The children glanced at one another.

“I was telling her all about it,” said Rachel. “About the Pyramid, you know, and Babylon, and the statue at Rhodes. I wouldn’t have told anyone else, but when I found that she was a ‘seven’ girl too——”

“But before that?” interrupted Mr. Sheston, settling himself comfortably into an arm-chair.

“We were talking about Diana,” said the other Diana. “It’s my name, and Rachel had been reading about her in the Bible. And my father painted a picture of her, so she was asking me about it.”

“Well,” returned Mr. Sheston, “let’s go on talking about Diana, because there’s a great deal to say. There was a famous temple built for her once upon a time, wasn’t there? Where was it?”

“At Ephesus,” said Rachel promptly.

“And where is Ephesus?”

“In Asia Minor,” answered Rachel again. “By the sea. Not so very far from Rhodes,” she added, with a meaning glance.

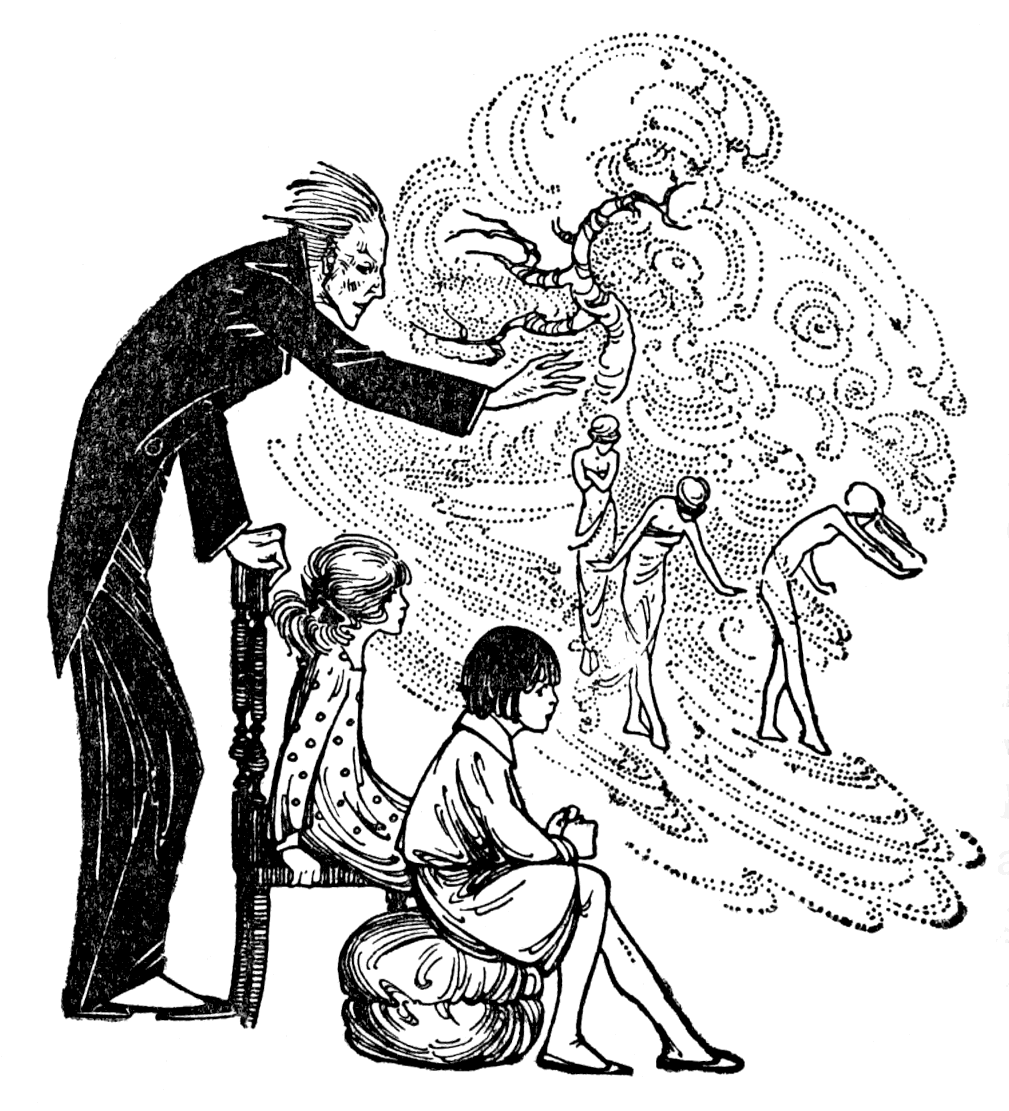

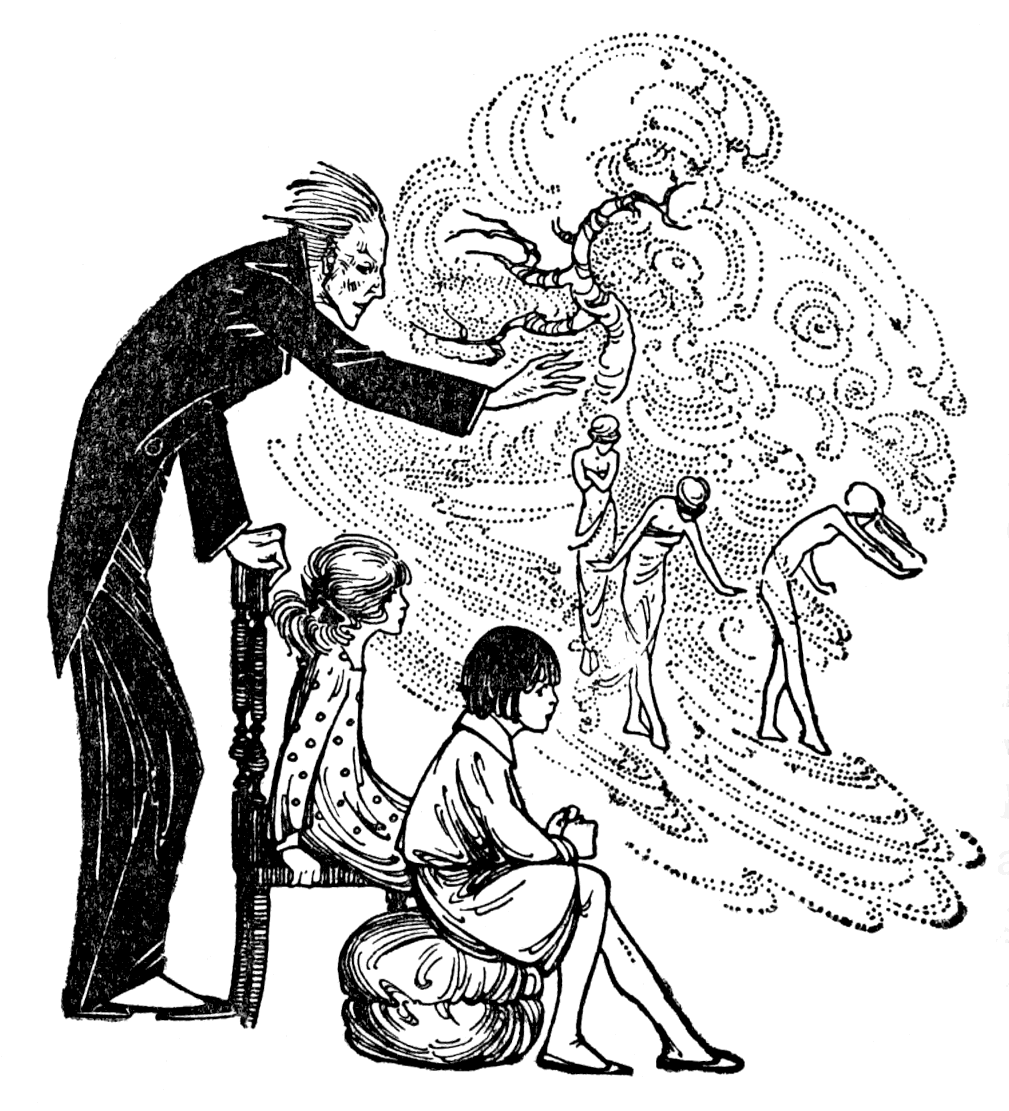

Mr. Sheston got up, and to the children’s surprise, altered the position of his arm-chair till it faced the window. Then he fetched two other chairs, and placed one on either side of his own seat. This done, he took from his coat pocket a leather case, and out of the case drew a photograph. Then he pointed to the two small chairs on either side of the big one.

“Sit down, one on each side of me,” he said.

When the children, too interested and puzzled to ask questions, had done as he directed, he held the picture in such a position that both of them could see what it represented.

“Is it the temple of Diana?” ventured Rachel as she glanced at the photograph of a huge building.

“Well, not the picture of the temple itself, because that has ceased to exist, and lies buried under ruins. But it’s a picture of what scholars think the temple must have been like when it was standing.... And they’re not very far out,” he added. But this he murmured as though to himself, as he again rose and walked towards the window. Rachel and Diana watched him breathlessly while he propped the photograph against the rim of one of the glass panes. After this had been successfully accomplished, he returned to his seat, and looking from one little girl to the other, said, “Stand up. Close your eyes. Bow seven times in the direction of the picture.”

The children exchanged glances before they obeyed.

“Open your eyes.” These were the next words—and they were necessary, for till they were spoken, both of them felt all at once so drowsy that they had no wish to raise their eyelids.

At the command, however, four eyes flew open in eager expectation—of what, their owners scarcely knew. The scene they actually beheld was surprising enough to force a little scream of astonishment from both of them—even though Rachel, who had been through “adventures” before, guessed at fresh wonders to follow.

The square-paned window, with its prospect of a road along which omnibuses, carts and cabs travelled, and people went to and fro, had vanished. They were looking into the open air.

A mist like a shimmering white veil obscured everything but the sky, which was intensely blue, and though the children strained their eyes, they could discern nothing beyond, except, perhaps, something that might, or might not, be trees. They were just vague shapes behind the soft wall of mist.

“You shall see more than this in a moment.”

Mr. Sheston’s voice was close to them, but as Rachel and Diana turned their heads to look at him they found that neither he nor anything within the room was visible. It was as though they sat in a darkened theatre looking out upon a stage. “And the curtain hasn’t gone up properly yet,” thought Rachel, full of tremulous anticipation.

“I’ll tell you why the curtain hasn’t gone up yet,” Mr. Sheston’s voice continued, and Rachel gave a little jump of surprise—for she had not spoken her thought aloud. Oh, certainly, as Salome in Babylon had said, Sheshà was “the greatest of all magicians!”

“You will understand presently how Diana’s temple at Ephesus began,” Mr. Sheston went on. “What I am going to tell you now is legend—that is to say, something that has been repeated from father to son for a great many years, always altered a little in the telling, so that though there may be, and probably is, some truth in the story, we can’t say how much is true and how much false. Well, the legend part of the story, you see, is rather like the mist full of vague shapes which you’re looking at now. I’m going to tell you the legend part—but, directly we come to what we really know, the curtain will go up.

“Once upon a time, then, in the country we now call Asia Minor, the women were taught (or perhaps taught themselves) to do all the hard and all the fierce work generally done by men. The little girls learnt to hurl spears called javelins, and to shoot with bow and arrows, and when they grew up were brave fighters. They also tilled the ground, and gathered the harvest, and built houses, and in fact did everything of that sort as well as men. They were called Amazons, and even great men-warriors found them powerful enemies. According to the old story it was they—these Amazons—who founded the city of Ephesus. That is, they were the first people to cultivate the land and to build houses where the magnificent city of Ephesus afterwards stood. It was these strange and wonderful women who first worshipped Diana in the woods and groves near the dwelling-places they had built. And it was quite natural they should worship the sort of goddess they imagined, for all wild life was her kingdom. So the Amazons, being themselves huntresses and fighters, loved and reverenced her. Forest creatures like the deer and wild boars belonged to her as the goddess of hunting, and she was also the protectress of all young human creatures—girls as well as boys. Thus, even in times so far away that there is no real history about them, there were altars where Diana was worshipped, and, legend tells us, the first altars set up in her honour were in, or near, the city of Ephesus, founded by the Amazons. At first these were very simple altars, for neither men—nor even women—had yet learnt to build temples.

“In a moment the mist-curtain will go up, and you shall see the sort of altar that once stood, where, afterwards, temples were built, and at last that most splendid one of all, which was called a Wonder of the World.” ... Mr. Sheston paused.

“We have done with legend now,” he went on after a moment, “and all you will see is what has actually happened in the past.”

Neither of the children spoke, but they watched in breathless suspense to see the curtain of mist shake and begin slowly to dissolve. First, tall pointed trees began to prick through the fog, then a glimpse of blue sky became visible. Next there was a gleam of sunshine on low white roofs, and at last, clear and distinct, a lovely country lay spread out before their eyes. They seemed to be looking at it as one might sit on a terrace overhanging a wide view, yet close enough to the nearer trees as almost to be able to touch them. Warm air in gentle puffs flowed towards them, and the sun was hot upon their faces and hands.

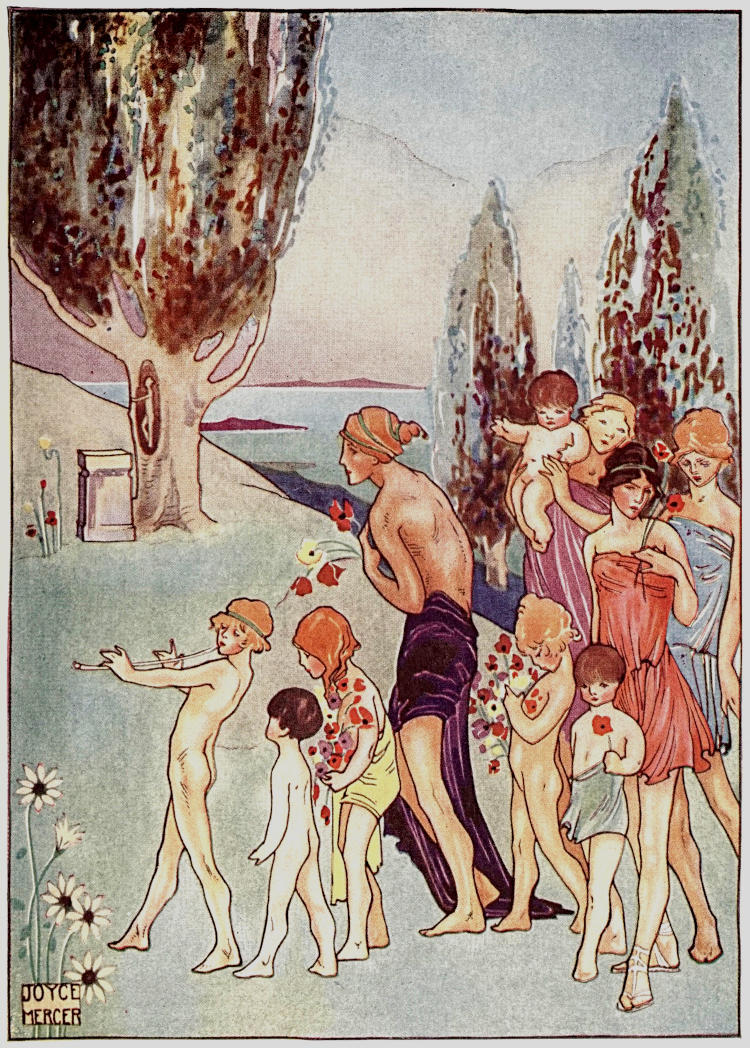

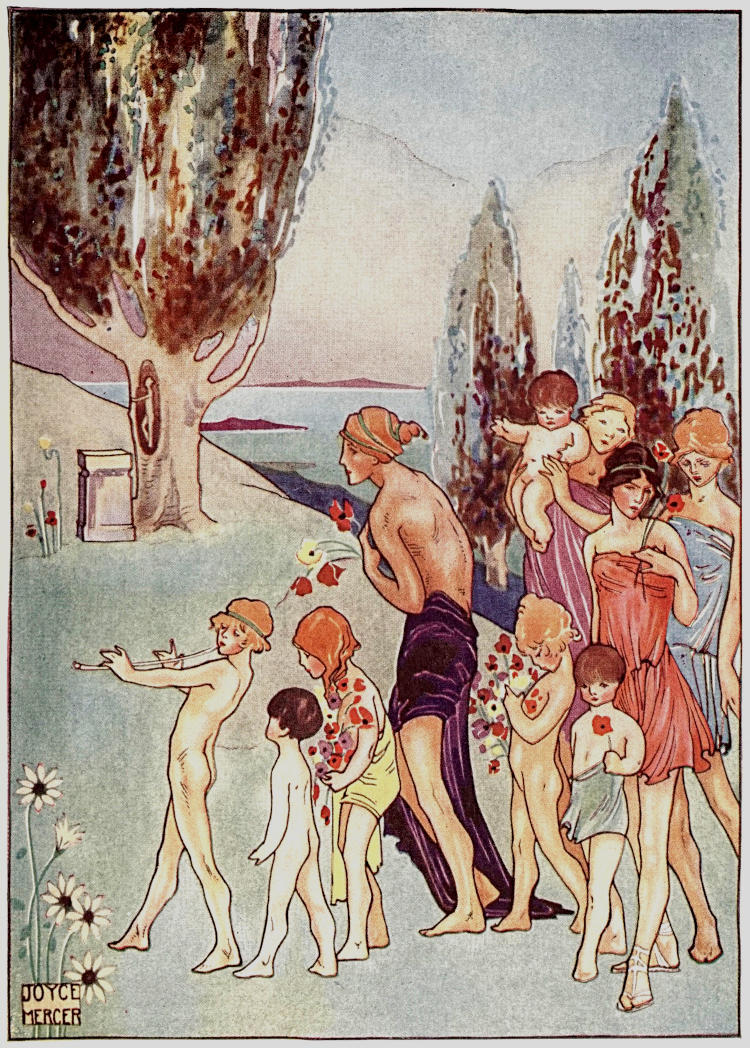

A LITTLE BOY WALKED IN FRONT OF THE PROCESSION

They saw in the distance a cluster of simple houses between trees, which Rachel guessed rightly to be the earliest city of Ephesus. Beyond these houses, lay the deeply blue sea, stretching away, away towards the distant shores of Greece opposite, with here and there a rocky island set in the blue. The land between the sea and the point nearest to them, was all hill and dale—the hills covered with stiff cypress trees like dark torches against the sky, mingled with graceful smaller and lighter trees. But just in front, and quite close, there was an open glade, and in the midst of it an altar made of piled-up stones. The altar was overshadowed by a big tree, and hanging from the lowest branch the children could see a little figure carved very roughly in wood.

Just as they noticed this, the sound of faint music—so faint, so remote that they could only hear it because of the absolute stillness, made them look quickly to the left of the altar. There, at a little distance, between the trees they saw approaching a company of women and children. The smaller children were almost naked, and their tiny bodies showed white against the dark background of the wood. The women wore short tunics with strips of leather bound in a criss-cross fashion round their bare legs. A little boy, with nothing but the skin of some wild animal hanging from his shoulders, walked in front of the procession, proudly blowing into a small pipe made of a hollow reed. The other children also had reed-pipes in their hands, and most of them carried armfuls of poppies. They crossed the glade and gathered in front of the altar upon which the women as well as the children began to scatter the poppies.

For a long minute Rachel and Diana watched the little scene, scarcely daring to breathe, in case it should vanish before their eyes. Then it did vanish! Blue sea, blue sky, hills and valleys, the small town in the distance, the glade with its altar, the group of people about it with their flowers, were all swallowed up in the white mist.

The children, spellbound and silent, while the beautiful scene lasted, now found their tongues loosened.

“Oh, what a darling little boy—the one with the fur over his shoulders,” exclaimed Diana. “Oh, how lovely the sea looked, and the blue sky, and the woods!” cried Rachel, excitedly. “And didn’t the children look pretty bringing their flowers? But they were all poppies. Why did they all bring poppies?”

“Because the poppy was the flower sacred to Diana. Nearly all the gods and goddesses of Greece and the Greek colonies had flowers, as well as animals that were specially theirs. And poppies belonged to the goddess Diana. But now, if you want to see anything more, you mustn’t speak again.”

The children subsided at once into silence, and Mr. Sheston went on talking.

“You noticed the little naked boy who led the procession to the altar in the glade? Keep him in mind, for it was he who built the first real temple to Diana. Listen, and I will tell you all I know about him.

“He was called Dinocrates, and his home was in Ephesus (you saw the town in the distance, a mile or two from the glade). At the time when Dinocrates was young, the city was small, the wild country stretched up close to its walls, and the boy lived nearly all day long in the open air.

“His father taught him to hunt, and he learnt so quickly to hurl the javelin and to shoot with bow and arrows, that everyone said he was specially favoured by Diana. The belief that the goddess was watching over him made Dinocrates, even as a tiny boy, very happy, and filled him with courage so that he was always successful in the chase, and even grown-up men marvelled at his wonderful skill. It was so well-known that he was a child greatly loved by Diana that whenever there was a festival in her honour, Dinocrates was always chosen to lead the procession, and to be the first to place his offerings of poppies on her altar. And later, when he was a little older, he was allowed to sacrifice in her honour an animal he had killed in the chase. So the boy grew up with a great love and reverence for Diana, and a longing to serve her in some special way that would shew his gratitude for her protection. He soon grew dissatisfied with the altar of stones, and the rough image on the trunk of her sacred tree, and in secret dreamt of some dwelling worthy of the goddess, which should last, and not be liable to destruction like the loosely built altar and the image exposed to the air.

“As time went on, he found that skill in hunting was not his only gift. He liked to plan houses, and he soon began to plan better ones than had ever been built before. By the time he was a man, he was the most famous architect in Ephesus, and many new buildings in the city began to rise, designed by him. But the dream of his life was to build a dwelling-place for his special goddess on the very spot where as a child, with other children, he had worshipped her out of doors under the sacred tree.

“It must be a real temple, and a temple different from, and better in every way than any of the attempts yet made by other men to fashion dwelling-places for the gods. So he worked and thought and imagined, and at last a little marble building, supported by pillars different from any other pillars yet designed, actually covered the spot of the original altar.

“The day his temple was finished was the happiest day of his life. There was a great festival, and from the city, crowds of people had come to worship Diana for the first time under a roof, and to gaze at the building itself. Small and simple, it was yet the most wonderful they had ever seen, with its columns of an entirely new shape, and its marble porch. And everyone was loud in the praise of its architect.

“That night, Dinocrates was too happy to sleep. He lay thinking of the temple which had been his life work, till suddenly a great desire to see it again swept over him. So he got up, dressed, and began to walk quickly in its direction. In half an hour he reached the glade in the heart of which stood the temple, and before long he saw it gleaming through the encircling trees. Dinocrates stopped short in delight at the beauty of the scene. There was a full moon, and its silver light poured down upon the little white building and made it dazzling to behold. Graceful shadows from the trees trembled upon its roof, and lay in long bars across the grass, and in the deep silence he could hear his heart beating. All at once, another sound made him start—the sound of a horn coming from far away, very faint and sweet! And then, scarcely trusting his eyes, he saw in the distance through the misty avenues of trees, white forms moving. They came nearer, rushing over the grass as though blown softly by an invisible wind, and through the silvery haze he caught a glimpse of white arms, and beautiful faces, and of one face more lovely than the rest, with cloudy hair in which something in shape like a crescent moon, sparkled and shone.

“For a second he saw the forms of beautiful women sweeping up the steps towards the door of the temple, and then the vision disappeared. There was only the moonlight on the grass, and the shadows, and silence.

“‘The goddess herself takes possession of her temple,’ thought Dinocrates. ‘And mortals cannot see the gods and live.’

“He felt so happy, and yet so tired, that he sank down before the temple to rest, and the glade was all full of sunshine before the people who had come to look for him found him lying there, and saw that he was dead....”

“Oh,” whispered Diana after a moment, “that’s an awfully sad story.”

“No,” said Rachel’s voice on the other side of Mr. Sheston’s arm-chair. “Not really. Because he came back again. In another life, you know. You’ll see in a minute. She will see him again, won’t she?” In the darkness Rachel turned towards Mr. Sheston.

“The story isn’t finished yet,” he replied. “Let me go on with it.

“Dinocrates died in that life, as Rachel says, and hundreds of years passed. That first temple with the columns of a new shape was at last destroyed by fire, and a new temple took its place, much larger, much more splendid, as you will see in a moment. But the architect who planned the second building copied those pillars invented by Dinocrates, so though his temple had been destroyed, his work you understand, in a way, went on. Now you are going to see that second temple, still on the same place or site, as it is called, of the first altar in the glade. And you shall see Dinocrates also—again as a little boy. Before you see him, however, I may tell you that he doesn’t remember anything about himself or his life many years before. Remember that hundreds of years have passed between the life-time of those simple people you have just seen and the people you are going to see now. Even they lived six hundred years before the birth of Christ. But, as you will discover, they had already learnt to make wonderful buildings.

“Shut your eyes again. Bow seven times—and many years will have gone by.”

The white mist was again dissolving when the children opened their eyes and looked eagerly to see what changes had taken place during the time that had magically flown.

Unaltered were the blue sky and the blue sea; unaltered the hills, unaltered many of the woods, though some of them had been cut down and houses and gardens had taken their place. The little white town in the distance, however, had grown into a large city, whose houses were now big and imposing. But the greatest change of all had taken place in what was once the glade and then (though they had not actually seen it) the first small temple.

A white marble building, covering a great stretch of ground, now rose in front of the children—a beautiful temple with arcades of lofty pillars wonderfully carved, and thronging upon the steps leading to the wide open doors was a multitude of people. They were gracefully clo