CHAPTER II

JAMES II: WITH THE FIERY FACE

It is clear that the public opinion of Scotland, so far as there was such a thing in existence, had no sympathy whatever with the murderers of James. The instruments of that murder were in the first place Highland caterans, with whom no terms were ever held and against whom every man's hand was armed. And the leaders who had taken advantage of these wild allies against their natural monarch and kindred were by the very act put beyond the pale of sympathy. They were executed ferociously and horribly, according to the custom of the time, the burghers of Perth rising at once in pursuit of them, and the burghers of Edinburgh looking on with stern satisfaction at their tortures—these towns feeling profoundly, more perhaps than any other section of the community, the extraordinary loss they had in the able and vigorous King, already, like his descendant and successor, the King of the commons, their stay and encouragement. If there was among the nobility less lamentation over a ruler who spared none of them on account of his race, and was sternly bent on repressing all abuse of power, it was silent in the immense and universal horror with which the event filled Scotland. It would seem probable that the little heir, only six years old, the only son of King James, was not with his parents in their Christmas rejoicings at Perth, but had been left behind at Holyrood, for we are told that the day after his father's death the poor little wondering child was solemnly but hastily crowned there, the dreadful news having flown to the centre of government. He was "crownd by the nobilitie," says Pitscottie, the great nobles who were nearest and within reach having no doubt rushed to the spot where the heir was, to guard and also to retain in their own hands the future King. He was proclaimed at once, and the crown, or such substitute for it as could be laid sudden hands upon, put on his infant head. The scene is one which recurred again and again in the history of his race, yet nothing can take from it its touching features. At six years old even the intimation of a father's death, especially when taking place at a distance, would make but a transitory impression upon the mind; yet we may well imagine the child taken from his toys, wrapped from head to foot in some royal mantle, with a man's crown held over his baby head, receiving with large eyes of wonder and fright easily translated into tears, the sacred oil, the sceptre which his little fingers could scarcely enclose. Alas for the luckless Stewarts! again and again this affecting ceremony took place before the time of their final promotion which was the precursor of their overthrow. They were all kings almost from their cradle—kings ill-omened, entering upon their royalty with infant terror and tears.

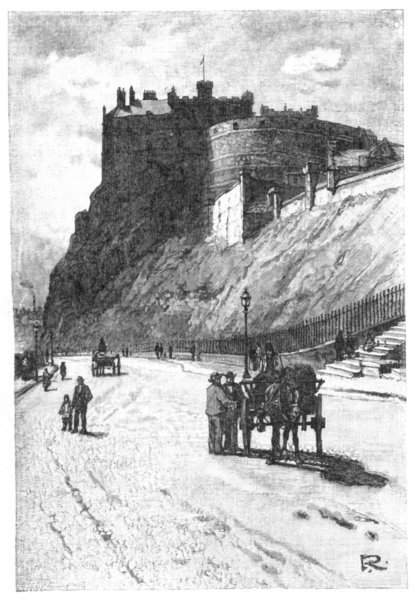

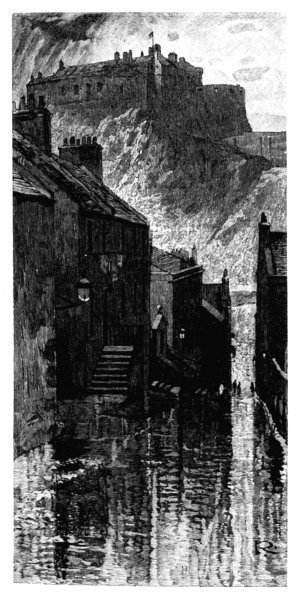

EDINBURGH CASTLE FROM THE SOUTH-WEST

When they had crowned the little James, second of the name, the lords held a convention "to advise whom they thought most able both for manheid and witt to take the government of the commonwealth in hand." They chose two men for this office, neither of whom was taken from a very great family, or had, so far as can be known, any special importance—Sir Alexander Livingstone, described as Knight of Callender, and Sir William Crichton, Chancellor of Scotland. Perhaps it was one of the compromises which are so common when parties are nearly equal in power which thus placed two personages of secondary importance at the head of affairs: but any advantage which might have been secured by this selection was neutralised by the division of power, which added to all the evils of an interregnum the perplexity of two centres of government, so that "no man knew," as says Pitscottie, "whom he should obey." One of the Regents reigned in Edinburgh, the other in Stirling—one had the advantage of holding possession of the King, the other had the doubtful good of the support of the Queen. It may be imagined what an extraordinary contrast this was to the firm and vigilant sway of a monarch in the fulness of manhood, with all the prestige of his many gifts and accomplishments, his vigorous and manful character and his unquestioned right to the government and obedience of the country. It had been hard work enough for James I., with all these advantages, to keep his kingdom well in hand: and it would not be easy to exaggerate the difficulties now, with two rival and feeble powers, neither great enough to overawe nor united enough to hold in check the independent power of the great houses which vied with each other in the display of dominion and wealth. In a very brief time all the ground gained by King James was lost again. Every element of anarchy arose in new force, and if it had been hard to secure the execution of the laws which would have been so good had they been kept in the time when their chief administrator was the King himself, it may be supposed what was the difficulty now, when, save in a little circuit round each seat of authority, there was virtually no power at all. Pitscottie gives a curious and vivid picture of the state of affairs in this lamentable interval.

"In the mean time many great dissensions rose amongst us, but it was uncertain who were the movers, or by what occasion the chancellor exercised such office, further than became him. He keeped both the Castle of Edinburgh and also our young King thereintill, who was committed to his keeping by the haill nobilitie and ane great part of the noble men assisted to his opinion. Upon the other side, Sir Alexander Livingstoun bearing the authoritie committed to him by consent of the nobilitie, as said is, contained another faction, to whose opinion the Queen mother with many of the nobility very trewly assisted. So the principals of both the factions caused proclaime lettres at mercat crosses and principal villages of the realm that all men should obey conforme to the aforesaid letters sent forth by them, under the pain of death. To the which no man knew to whom he should obey or to whose letters he should be obedient unto. And also great trouble appeared in this realm, because there was no man to defend the burghs, priests, and poor men and labourers hauntind to their leisum (lawful) business either private or public. These men because of these enormities might not travel for thieves and brigands and such like: all other weak and decrepit persons who was unable to defend themselves, or yet to get food and sustentation to themselves, were most cruelly vexed in such troublous times. For when any passed to seek redress at the Chancellor of such injuries and troubles sustained by them, the thieves and brigands, feigning themselves to be of another faction, would burn their house and carry their whole goods and gear away before ever they returned again. And the same mischief befell those that went to complain to the Governor of the oppression done to them. Some other good men moved upon consideration and pitie of their present calamities tholed (endured) many such injuries, and contained themselves at home and sought no redresse. In the midst of these things and troubles, all things being out of order, Queen-Mother began to find out ane moyane (a means) how she should diminish the Chancellor's power and augment the Governor's power, whose authority she assisted."

The position of Queen Jane in the circumstances in which her husband left her, a woman still young, with a band of small children, and no authority in the turbulent and distracted country, is as painful a one as could well be imagined. Her English blood would be against her, and even her beauty, so celebrated by her chivalrous husband, and which would no doubt increase the immediate impulse of suitors, in that much-marrying age, towards the beautiful widow who was of royal blood to begin with and still bore the title of Queen. That she seems to have had no protection from her royal kindred is probably explained by the fact that Henry VI was never very potent or secure upon his throne, and that the Wars of the Roses were threatening and demanding the whole attention of the English Government. Wounded in her efforts to protect her husband by her own person, seeing him slaughtered before her eyes, there could not be a more terrible moment in any woman's life, hard as were the lives of women in that age of violence, than that which passed over Jane Beaufort's head in the Blackfriars Monastery amid the blood and tumult of that fatal night. The chroniclers, occupied by matters more weighty, have no time to picture the scene that followed that cruel and horrible murder, when the distracted women, who were its only witnesses, after the tumult and the roar of the murderers had passed by, were left to wash the wounds and compose the limbs of the dead King so lately taking his part in their evening's pastime, and to look to the injuries of the Queen and the torn and broken arm of Catherine Douglas, a sufferer of whom history has no further word to say. The room with its imperfect lights rises before us, the wintry wind rushing in by those wide-open doors, waving about the figures on the tapestry till they too seemed to mourn and lament with wildly tossing arms the horror of the scene—the cries and clash of arms as the caterans fled, pausing no doubt to pick up what scattered jewels or rich garments might lie in their way: and by the wild illumination of a torch, or the wavering leaping flame of the faggot on the hearth, the two wounded ladies, each with an anxious group about her—the Queen, covered with her own and her husband's blood; the girl, with her broken wrist, lying near the threshold which she had defended with all her heroic might. They were used to exercise the art of healing, to bind up wounds and bring back consciousness, these hapless ladies, so constantly the victims of passion and ambition. But amid all the horrors which they had to witness in their lives, horrors in which they did not always take the healing part, there could be none more appalling than this. Neither then nor now, however, is it at the most terrible moment of life, when the revolted soul desires it most, that death comes to free the sufferer. The Queen lived, no doubt, to think of the forlorn little boy in Holyrood, the five little maidens who were dependent upon her, and resumed the burden of life now so strangely different, so dull and blank, so full of alarms and struggles. Her elder child, the little Princess Margaret, had been sent to France three or four years before, at the age of ten, to be the bride of the Dauphin—a great match for a Scottish princess—and it is possible that her next sister, Eleanor, who afterwards married the Duc de Bretagne, had accompanied Margaret—two little creatures solitary in their great promotion, separated from all who held them dear. But the four infants who were left would be burden enough for the mother in her unassured and unprotected state. It would seem that she was not permitted to be with her boy, probably because of the jealousy of the Lords, who would have no female Regent attempting to reign in the name of her son: but had fixed her residence in Stirling under the shield of Livingstone, who as Governor of the kingdom ought to have exercised all the functions of the Regency, and especially the most weighty one, that of training the King. Crichton, however, who was Chancellor, had been on the spot when James II was crowned, and had secured his guardianship by the might of the strong hand, if no other, removing him to Edinburgh Castle, where he could be kept safe under watch and ward. The Queen, who would seem to have been throughout of Livingstone's faction, and who no doubt desired to have her son with her, both from affection and policy, set her wits to discover a "moyane," as the chroniclers say, of recovering the custody of the boy. The moyane was simple and primitive enough, and might well have been pardoned to a mother deprived of her natural rights: but it shows at the same time the importance attached to the possession of the little King, when it was only in such a way that he could be secured. Queen Jane set out from Stirling "with a small train" to avert suspicion, and appeared at the gates of Edinburgh Castle suddenly, without warning as would seem, asking to be admitted to see her son. The Chancellor, wise and wily as he was, would appear to have acknowledged the naturalness of this request, and "received her," the chronicler says, "with gladness, and gave her entrance to visit her young son, and gave command that whensoever the Queen came to the castle it should be patent to Her Grace." Jane entered the castle accordingly, with many protestations of her desire for peace and anxiety to prevent dissensions, all which was, no doubt, true enough, though the chroniclers treat her protestations with little faith, declaring her to have "very craftilie dissembled" in order to dispel any suspicion the Chancellor may have entertained. It would seem that she had not borne any friendship to him beforehand, and that her show of friendship now required explanation. However that might be, she succeeded in persuading Crichton of her good faith, and was allowed to have free intercourse with her son and regain her natural place in his affections. How long they had been separated there is no evidence to show, but it could scarcely be difficult for the mother to recover, even had it fallen into forgetfulness, the affection of her child. When she had remained long enough in the castle to disarm any prejudices Crichton might entertain of her, and to persuade the little King to the device which was to secure his freedom, the Queen informed the Chancellor that she was about to make a pilgrimage to the famous shrine of Whitekirk, "the white kirk of Brechin," Pitscottie says, in order to pray for the repose of the soul of her husband and the prosperity of her son, and asked permission to carry away two coffers with her clothes and ornaments, probably things which she had left in the castle before her widowhood, and that means of conveyance might be provided for these possessions to Leith, where she was to embark. This simple request was easily granted, and the two coffers carried out of the castle, and conveyed by "horss" to the ship in which she herself embarked with her few attendants. But instead of turning northward Queen Jane's ship sailed up the Firth, through the narrow strait at Queensferry, past Borrowstounness, where the great estuary widens out once more, into the quiet waters of the Forth, winding through the green country to Stirling on its hill. She was "a great pairt of the watter upward before ever the keepers of the castle could perceive themselves deceived," says Pitscottie. As the ship neared Stirling, the Governor of the kingdom came out of the castle with all his forces, with great joy and triumph, and received the King and his mother. For one of the coffers, so carefully packed and accounted for, contained no less an ornament than the little King in person, to whose childish mind no doubt this mode of transport was a delightful device and pleasantry. One can imagine how the Queen's heart must have throbbed with anxiety while her son lay hidden in the bed made for him within the heavy chest, where if air failed, or any varlet made the discovery prematurely, all her hopes would have come to an end. She must have fluttered like a bird over her young about the receptacle in which her boy lay, and talked with her ladies over his head to encourage and keep him patient till the end of the journey was near enough, amid the lingering links of Forth, to open the lid and set him free. It is not a journey that is often made nowadays, but with all the lights of the morning upon Demayat and his attendant mountains, and the sun shining upon that rich valley, and the river at its leisure wending, as if it loved them, through all the verdant holms and haughs, there is no pleasanter way of travelling from Edinburgh to Stirling, the two hill-castles of the Scottish crown.

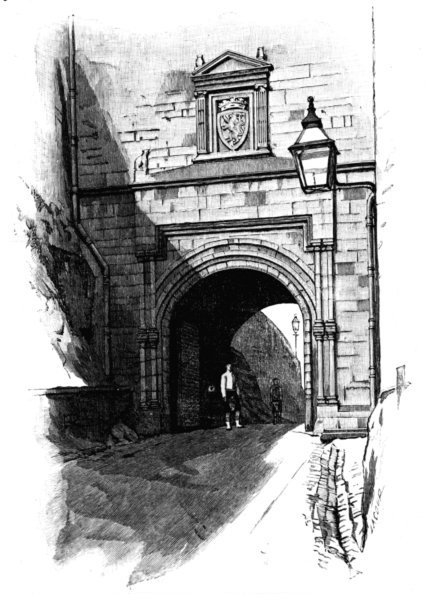

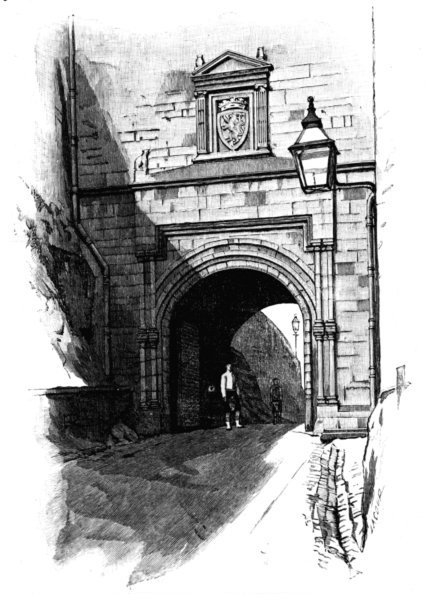

INNER BARRIER, EDINBURGH CASTLE

It would be pleasant to think that Queen Jane meant something more than the mere bolstering up of one faction against another in the distracted kingdom by the abduction of her son. It is very possible indeed that she did so, and that to strengthen the hands of the man who was really Regent-Governor of Scotland, but whose power had been stolen from his hands by the unscrupulousness of Crichton, seemed to her a great political object, and the recovery of the supreme authority, which would seem to have appeared to all as infallibly linked with the possession of the young King, of the greatest importance. It is evident it was considered by the general public to be so; but there is something pitiful in the struggle for the poor boy, over whose small person those fierce factionaries fought, and in whose name, still so innocent and helpless as he was, so many ferocious deeds were done.

No sooner was he secure in Stirling than the Governor called together a convention of his friends, to congratulate each other and praise the wit and skill of "that noble woman, our soverain mother," who had thus set things right. "Whereby I understand," he says piously, "that the wisest man is not at all times the sickerest, nor yet the hardy man happiest," seeing that Crichton, though so great and sagacious and powerful, should be thus deceived and brought to shame. "Be of good comfort therefore," adds this enlightened ruler; "all the mischief, banishment, troubles, and vexation which the Chancellor thought to have done to us let us do the like to him." He ended this discourse by an intimation that he was about to besiege Edinburgh. "Let us also take up some band of men-of-war, and every man after his power send secret messages to their friends, that they and every one that favours us may convene together quietly in Edinburgh earlie in the morning, so that the Chancellor should not know us to come for the sieging of the castle till we have the siege even belted about the walls; so ye shall have subject to you all that would have arrogantly oppressed you."

This resolution was agreed to with enthusiasm, the Queen undertaking to provision the army "out of her own garners"; but the Governor had no sooner "belted the siege about the castle," an expression which renders most graphically the surrounding of the place, than the Chancellor, taken by surprise, prostrated by the loss of the King, and finding it impossible to draw the powerful Earl of Douglas to his aid, made overtures of submission, and begged for a meeting "in the fields before the gates," where, with a few chosen friends on either side, the two great functionaries of the kingdom might come to an agreement between themselves.

By this time there would seem to have begun that preponderating influence of the Douglas family in Scotland which vexed the entire reign of the second James, and prompted two of the most violent and tragic deeds which stain the record of Scottish history. James I. was more general in his attempt at the repression and control of his fierce nobility, and the family most obnoxious to him was evidently that of his uncle, nearest in blood and most dangerous to the security of the reigning race. The Douglas, however, detaches himself in the following generation into a power and place unexampled, and which it took the entire force of Scotland, and all the wavering and uncertain expedients of law, as well as the more decisive action of violence quite lawless, to put down. Whether there was in the pretensions of this great house any aim at the royal authority in their own persons, or ambitious assertion of a rival claim in right of the blood of Bruce, which was as much in their veins as in those of the Stewarts, as some recent historians would make out, it is probably now quite impossible to decide. The chroniclers say nothing of any such intention, nor do the Douglases themselves, who throughout the struggle never hesitated to make submission to the Crown when the course of fortune went against them. The Chancellor had been deeply stung, it is evident, by the answer of Douglas to his appeal, in which the fierce Earl declared that discord between "you twa unhappie tyrants" was the most agreeable thing in the world to him, and that he wished nothing more than that it should continue. Deprived of the sanction given to all his proceedings by the name of the King, outwitted among his wiles, and exposed to the ridicule even of those who had regarded his wisdom with most admiration, Crichton would seem to have turned fiercely upon the common opponent, perhaps with a wise prescience of the evil to come, perhaps only to secure an object of action which might avert danger from himself and bring him once more into command of the source of authority—most likely with both objects together, the higher and lower, as is most general in our mingled nature. The meeting was held accordingly outside the castle gates, the Chancellor coming forth in state bearing the keys of the castle, which were presented, Buchanan says, to the King in person, who accompanied the expedition, and who restored the great functionary to his office. The great keys in the child's hand, the little treble pipe in which the reappointment would be made, the tiny figure in the midst of all these plotters and warriors, gives a touch of pathos to the many pictorial scenes of an age so rich in the picturesque; but the earlier writers say nothing of the little James's presence. There was, however, a consultation between the two Regents, and Douglas's letter was read with such angry comments as may be supposed. The Earl's contempt evidently cut deep, and strongly emphasised the necessity of dealing authoritatively with such a high-handed rebel against the appointed rulers.

It would appear, however, that little could be done against the immediate head of that great house, and the two rulers, though they had made friends over this common object, had to await their opportunity, and in the meantime do their best to maintain order and to get each the chief power into his own hands. Crichton found means before very long to triumph over his adversaries in his turn by rekidnapping the little King, for whom he laid wait in the woods about Stirling, where James was permitted precociously to indulge the passion of his family for hunting. No doubt the crafty Chancellor had pleasant inducements to bring forward to persuade the boy to a renewed escape, for "the King smiled," say the chroniclers, probably delighted by the novelty and renewed adventure—the glorious gallop across country in the dewy morning, a more pleasant prospect than the previous conveyance in his mother's big chest. Thus in a few hours the balance was turned, and it was once more the Chancellor and not the Governor who could issue ordinances and make regulations in the name of the King.

Nothing, however, could be more tedious and trifling in the record than these struggles over the small person of the child-king. But the story quickens when the long-desired occasion arrived, and the two rulers, rivals yet partners in power, found opportunity to strike the blow upon which they had decided, and crush the great family which threatened to dominate Scotland, and which was so contemptuous of their own sway. The great Earl, Duke of Touraine, almost prince at home, the son of that Douglas whose valour had moved England, and indeed Christendom, to admiration, though he never won a battle—died in the midst of his years, leaving behind him two young sons much under age as the representatives of his name. It is extraordinary to us to realise the place held by youth in those times, when one would suppose a man's strength peculiarly necessary for the holding of an even nominal position. Mr. Church has just shown in his Life of Henry V how that prince at sixteen led armies and governed provinces; and it is clear that this was by no means exceptional, and that the right of boys to rule themselves and their possessions was universally acknowledged and permitted. The young William, Earl of Douglas, is said to have been only about fourteen at his father's death. He was but eighteen at the time of his execution, and between these dates he appears to have exercised all the rights of independent authority without tutor or guardian. The position into which he entered at this early age was unequalled in Scotland, in many respects superior to that of the nominal sovereign, who had so many to answer to for every step he took—counsellors and critics more plentiful than courtiers. The chronicles report all manner of vague arrogancies and presumptions on the part of the new Earl. He held a veritable court in his castle, very different from the semi-prison which, whether at Edinburgh or Stirling, was all that James of Scotland had for home and throne—and conferred fiefs and knighthood upon his followers as if he had been a reigning prince. "The Earl of Douglas," says Pitscottie, "being of tender age, was puffed up with new ambition and greater pride nor he was before, as the manner of youth is; and also prideful tyrants and flatterers that were about him through this occasion spurred him ever to greater tyranny and oppression." The lawless proceedings of the young potentate would seem to have stirred up all the disorderly elements in the kingdom. His own wild Border county grew wilder than ever, without control. Feuds broke out over all the country, in which revenge for injuries or traditionary quarrels were lit up of the strong hope in every man's breast not only of killing his neighbour, but taking possession of his neighbour's lands. The caterans swarmed down once more from the mountains and isles, and every petty tyrant of a robber laird threw off whatever bond of law had been forced upon him in King James's golden days. This sudden access of anarchy was made more terrible by a famine in the country, where not very long before it had been reported that there was fish and flesh for every man. "A great dearth of victualls, pairtly because the labourers of the ground might not sow nor win the corn through the tumults and cumbers of the country," spread everywhere, and the state of the kingdom called the conflicting authorities once more to consultation and some attempt at united action.

The meeting this time was held in St. Giles's, the metropolitan church, then, perhaps, scarcely less new and shining in its decoration than now, though with altars glowing in all the shadowy aisles and the breath of incense mounting to the lofty roof. There would not seem to have been any prejudice as to using a sacred place for such a council, though it might be in the chapter-house or some adjacent building that the barons met. It is to be hoped that they did not go so far as to put into words within the consecrated walls the full force of their intention, even if it had come to be an intention so soon. There was but a small following on either side, that neither party might be alarmed, and many fine speeches were made upon the necessity of concord and mutual aid to repress the common enemy. The Chancellor, having restolen the King, would no doubt be most confident in tone; but on both sides there were equal professions of devotion to the country, and so many admirable sentiments expressed, that "all their friends on both sides that stood about began to extol and love them both, with great thanksgiving that they both regarded the commonwealth so mickle and preferred the same to all private quarrels and debates." The decision to which they came was to call a Parliament, at which aggrieved persons throughout the country might appear and make their complaints. The result was a crowd of woeful complainants, "such as had never been seen before. There were so many widows, bairns, and infants seeking redress for their husbands, kin, and friends that were cruelly slain by wicked murderers, and many for hireling theft and murder, that it would have pitied any man to have heard the same." This clamorous and woeful crowd filled the courts and narrow square of the castle before the old parliament-hall with a murmur of misery and wrath, the plaint of kin and personal injury more sharp than a mere public grief. The two rulers and their counsellors no doubt listened with grim satisfaction, feeling their enemy delivered into their hands, and finding a dreadful advantage in the youth and recklessness of the victims, who had taken no precaution, and of whom it was so easy to conclude that they were "the principal cause of these enormities." Whether their determination to sacrifice the young Douglas, and so crush his house, was formed at once, it is impossible to say. Perhaps some hope of moulding his youth to their own purpose may have at first softened the intention of the plotters. At all events they sent him complimentary letters, "full of coloured and pointed words," inviting him to Edinburgh in their joint names with all the respect that became his rank and importance. The youth, unthinking in his boyish exaltation of any possibility of harm to him, accepted the invitation sent to him to visit the King at Edinburgh, and accompanied by his brother David, the only other male of his immediate family, set out magnificently and with full confidence with his gay train of knights and followers—among whom, no doubt, the youthful element predominated—towards the capital. He was met on the way by Crichton—evidently an accomplished courtier, and full of all the habits and ways of diplomacy—who invited the cavalcade to turn aside and rest for a day or two in Crichton Castle, where everything had been prepared for their reception. Here amid all the feastings and delights the great official discoursed to the young noble about the duties of his rank and the necessity of supporting the King's government and establishing the authority of law over the distracted country, sweetening his sermon with protestations of his high regard for the Douglas name, whose house, kin, and friends were more dear to him than any in Scotland, and of affection to the young Earl himself. Perhaps this was the turning-point, though the young gallant in his heyday of power and self-confidence was all unconscious of it; perhaps he received the advice too lightly, or laughed at the seriousness of his counsellor. At all events, when the gay band took horse again and proceeded towards Edinburgh, suspicion began to steal among the Earl's companions. Several of them made efforts to restrain their young leader, begging him at least to send back his young brother David if he would not himself turn homeward. "But," says the chronicler, "the nearer that a man be to peril or mischief he runs more headlong thereto, and has no grace to hear them that gives him any counsel to eschew the peril."

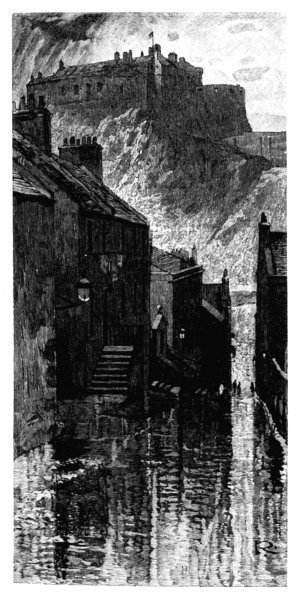

EDINBURGH CASTLE FROM THE VENNEL

The only result of these attempts was that the party of boys spurred on, more gaily, more confidently than ever, with the deceiver at their side, who had spoken in so wise and fatherly a tone, giving so much good advice to the heedless lads. They were welcomed into Edinburgh within the fatal walls of the Castle with every demonstration of respect and delight. How long the interval was before all this enthusiasm turned into the stern preparations of murder it seems impossible to say—it might have been on the first night that the catastrophe happened, for anything the chroniclers tell us. The followers of Douglas were carefully got away, "skailled out of the town," sent for lodging outside the castle walls, while the two young brothers were marshalled, as became their rank, to table to dine with the King. Whether they suspected anything, o