CHAPTER III

JAMES III: THE MAN OF PEACE

Again the noises cease save for a wail of lamentation over the dead. The operations of war are suspended, the dark ranks of the army stand aside, and every trumpet and fatal cannon is silent while once more a woman and a child come into the foreground of the historic scene. Once more, the most pathetic figure surely in history, a little startled boy clinging to his mother—not afraid indeed of the array of war to which he has been accustomed all his life, and perhaps with an instinct in him of childish majesty, the consciousness which so soon develops even in an infant mind, of unquestioned rank, but surrounded by the atmosphere of horror and affright in which he has been taken from among his playthings—stands forth to be hastily enveloped in the robes so pitifully over-large of the dead monarch. The lords, we are told, sent for the Prince in the first sensation of the catastrophe, and had him crowned at Kelso, feeling the necessity of that central name at least, round which to rally. They were not always respectful of the real King when they had him, yet the divinity which hedged the title, however helpless the head round which it shone, was felt to be indispensable to the unity and strength of the kingdom. Mary of Gueldres in her sudden widowhood would seem to have behaved with great dignity and spirit at this critical moment. She is said to have insisted that the siege should not be abandoned, but that her husband's death might at least accomplish what his heart had been set upon; and the army after a moment of despondency was so "incouraged" by the coming of the Prince "that they forgot the death of his father and past manfullie to the hous, and wan the same, and justified the captaine theroff, and kest it down to the ground that it should not be any impediment to them hereafter." The execution of the captain seems a hard measure unless he was a traitor to the Scottish crown; but no doubt the conflict became more bitter from the terrible cost of the victory.

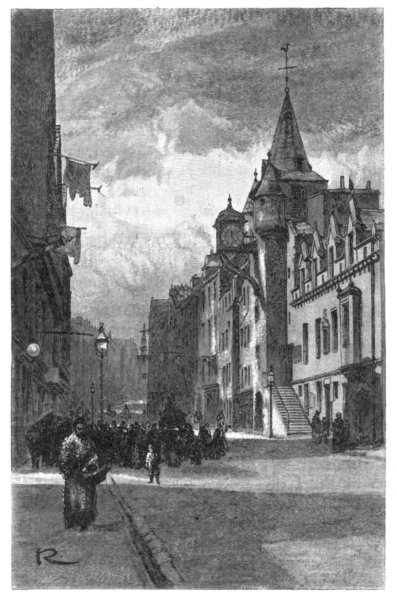

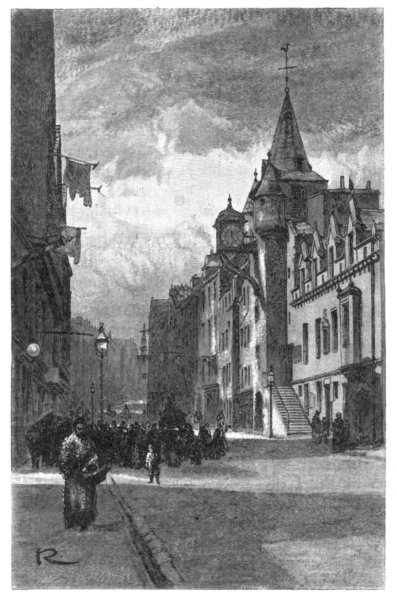

THE CANONGATE TOLBOOTH

Once more accordingly the kingdom was thrown into the chaos which in those days attended a long minority, the struggle for power, the relaxation of order, and all the evils that follow when one firm hand full of purpose drops the reins which half a dozen conflicting competitors scramble for. There was not, at first at least, anything of the foolish anarchy which drove Scotland into confusion during the childhood of James II, and opened the way to so many subsequent disasters, for Bishop Kennedy, the dead King's chief counsellor and support and a man universally trusted, was in the front of affairs, influencing if not originating all that was done: and to him, almost as a matter of course, the education of the little heir was at once confided. But Mary of Gueldres was a woman of resolution and force, and did not give up without a struggle her pretensions to the regency. Buchanan relates a scene which, according to his history, took place in Edinburgh on the occasion of the first Parliament after James's death. The Queen had established herself in the castle while Kennedy was in Holyrood, probably with his little pupil, but there is no mention made of James. On the second day of the Parliament Mary appeared suddenly in what would seem to have been, according to modern phraseology, "a packed house," her own partisans having no doubt been warned to be present by the action of some energetic "whip," and was, then and there, by a hasty Act, carried through at one sitting, appointed guardian and Regent, after which summary success she returned with great pomp to her apartments, though with what hope of having really attained a tenable position it is impossible to say. When the news was carried to Holyrood, Bishop Kennedy in his turn appeared before the Estates, which had been thus taken by surprise. It is evident that the populace of Edinburgh was excited by what had occurred—Mary's partisans no doubt rejoicing, while the people in general, always jealous of a foreigner and never very respectful of a woman, surged through the great line of street towards the castle with all the fury of a popular tumult. The High Street of Edinburgh was not unaccustomed to sudden encounters, clashing of swords between two passing lords, each with fierce followers, and all the risks of sudden brawls when neither would concede the "crown of the causeway." But the townsfolk seldom did more than look on, with perhaps an ill-concealed satisfaction in the wounds inflicted by their natural opponents upon each other. On this occasion, however, the tumult was a popular one, involving the interests of the citizens; and it is difficult to believe that the inclinations of the townsfolk would not rather lean towards the Queen, a woman of wealth and stately surroundings, likely to entertain princes and great personages and to fill Edinburgh with the splendour of a Court, than to the prelate, although his tastes also were magnificent, whose metropolis was not Edinburgh but St. Andrews, and who might consider frugality and sobriety the best qualities for the Court of a minor. At all events the crowd had risen and was ripe for tumult, when Bishop Kennedy persuaded them to pause, and reminded them of the mutual forbearance and patience and quiet which was above all necessary at such a troublous time. Other prelates would seem to have been in his train, for we are told it was the intercessions and explanations of "the bishops" which prevented the tumult from rising into a fight. The parties would seem to have been so strong, and so evenly divided, that the question was finally solved by a compromise, Parliament appointing a council of guardians, two on each side: Seaton and Boyd for the Queen; John Kennedy, brother of the Bishop, and the Earl of Orkney, for the others—an experiment which was no more successful than in the previous minority.

The Queen-mother had soon, however, something to occupy her leisure in the visit, if visit it can be called, of Henry VI and his Queen and household, fugitives before the victorious party of York, who had sought refuge from the Scots, and lodging for a thousand attendants—a request which was granted, and the convent of the Greyfriars allotted to them as their residence. The Queen at the Castle would thus be a near neighbour of the royal fugitives, and it is interesting to think of the meeting, the sympathy and mutual condolences of the two women. Margaret, the fervid Provençal, with her passionate sense of wrong and restless energy, and the hopeless task she had of maintaining and inspiring to play his part with any dignity her too patient and gentle king; and Mary, the fair and placid Fleming, stung too in her pride and affections by the refusal of the regency, and her subordination to those riotous and unmannerly lords and the proud Bishop who had got the affairs of Scotland in his hand. The two Queens might have had some previous acquaintance with each other, at a time when both had fairer hopes; at all events they amused themselves sadly, as they sat and talked together, with fancies such as please women, of making a marriage between the little Edward, the future victim of Tewkesbury, then a child at his mother's knee, and the little Princess of Scotland who played beside him, in the good days when all these troubles should be past, and Henry or his son after him should have regained the English crown. One follows with regretful interest the noble figure of Margaret, under the guise in which that sworn Lancastrian Shakspeare has disclosed it to us, before her sweeter mood had disappeared under the pressure of fate, and when not curses but hopes came from her mouth in her young motherhood, and every recovery and restoration, and happy marriage and royal state, were possible for her boy. Mary too had been cut off in the middle of her greatness. They were two Queens discrowned, two fair heads veiled with misfortune, though nothing irremediable had as yet happened, nothing that should make the future a desert though the present might be dark; ready to live again in their children, and make premature treaties over the little blonde heads at their knee. So natural a scene comes in strangely to the records of violence and misery. Nothing more tragic could be than the fate of Margaret; and the splendour and happiness had been very shortlived in Mary's experience, soon quenched in sudden destruction; but to see the two young mothers planning over the heads of the little ones how the two kingdoms were to be united, and happiness come back in a future that was never to be, while they sat together in brief companionship in those strait rooms of Edinburgh Castle, which were so narrow and so poor for a queen's habitation, or within the precincts of the Greyfriars, looking out upon the peaceful Pentlands and the soft hills of Braid, is like the recurring melody in a piece of stormy music, the bit of light in a tempestuous picture. It teaches us to perceive that, however the firmament of a kingdom may be torn with storms, there are everywhere about, even in queens' chambers, scenes of tenderness and peace.

Mary died in her own foundation of Trinity College Hospital—the beautiful church of which was demolished within living memory—three years after her husband, while her children were still very young: and thus all further struggles about the regency were ended. She does not seem indeed ever to have repeated her one stand for power. Bishop Kennedy, we may well believe, was not a man with whom there would be easy fighting. His sway procured a little respite for Scotland in the ordinary miseries of her career. The Douglases were safely out of the way and ended, and there was a truce of fifteen years with England which kept danger from that side at arm's length—not, the chroniclers assure us, from any additional love between the two countries, but because "the Inglish had warres within themselves daylie, stryvand for the crown." Kennedy lived some years after the Queen, guiding all the affairs of the kingdom so wisely that "the commounweill flourished greatly." He was a Churchman of the noblest kind, full of care for the spiritual interests of his diocese as well as for the secular affairs which were placed in his hands. "He caused all persones (parsons) and vicars to remain at their paroche kirks," says Pitscottie, "for the instruction and edifying of their flocks: and caused them preach the Word of God to the people and visit them that were sick; and also the said Bishope visited every kirk within the diocese four times in the year, and preached to the said parochin himself the Word of God, and inquired of them if they were dewly instructed by their parson and vicar, and if the poor were sustained and the youth brought up and learned according to the order that was taine in the house of God."

With all this, and many other gifts beside, among which are noted the knowledge he had of the "civil laws, having practised in the same," and his experience and sagacity in all public affairs—he was a scholar and loved all the arts. "He founded," says Pitscottie, "ane triumphant college in Sanct Androis, called Sanct Salvatore's College, wherein he made his lear (library) very curiouslie and coastlie; and also he biggit ane ship, called the Bishop's Barge, and when all three were complete, to wit, the college, the lear, and the barge, he knew not which of the three was the costliest; for it was reckoned for the time by honest men of consideration that the least of the three cost him ten thousand pound sterling." Major gives the same high character of the great Bishop, declaring that there were but two things in him which did not merit approval—the fact that he held a priory (but only one, that of Pittenweem) in commendam, "and the sumptuositie of his sepulchre." That sepulchre, half destroyed—after having remained a thing of beauty for three hundred years—by ignorant and foolish hands in the end of the eighteenth century, may still be seen in the chapel of his college at St. Andrews, the only existing memorial of the time when all Scotland was governed from that stormy headland to the great advantage of the commonwealth. It is difficult to make out from the different records whether the young King remained in the Bishop's keeping so long as he lived, which was but until James had attained the age of thirteen, or whether the usual struggle between the two sets of guardians appointed by Parliament, the Boyds and Kennedies, had begun before the Bishop's death. It may be imagined, however, that the evident advantages to the boy of Bishop Kennedy's care would outweigh any formal appointment; although at the same time the idea suggests itself whether in the perversity of human nature this training was not in itself partly the cause of James's weaknesses and errors. He would learn at St. Andrews not only what was best in the learning of the time, but as much of the arts as were known in Scotland, and especially that noble art of architecture, which has been the passion of so many princes. And no doubt he would see the advancement of professors of these arts, of men skilful and cunning in design and decoration, the builders, the sculptors, and the musicians, whose place in the great cathedral could never be unimportant. A Churchman could promote and honour such public servants in the little commonwealth of his cathedral town with greater freedom than might be done elsewhere; and James, a studious and feeble boy, not wise enough to see that the example of his great teacher was here inappropriate and out of place, learned this lesson but too well. The King grew up "a man that loved solitariness and desired never to hear of warre, but delighted more in musick and politie and building nor he did in the government of his realm." It would seem that he was also fond of money, which indeed was very necessary to the carrying out of his pursuits. It is difficult to estimate justly the position of a king of such a temperament in such circumstances, whether he is to be blamed for abandoning the national policy and tradition, or whether he was not rather conscientiously trying to carry out his stewardry of his kingdom in a better way when he withheld his countenance from the perpetual wars of the Border, and addressed himself to the construction of noble halls and chapels and the patronage of the arts. He was at least so far in advance of his time, still concerned with the rudest interests of practical life as to be universally misunderstood: and he had the further misfortune of sharing the unpopularity of the favourites with whom he surrounded himself, as almost every monarch has done who has promoted men of inferior position to the high places of the State.

James's supineness, over-refinement, and love of peaceful occupations were made the more remarkable from the contrast with two manly and chivalrous brothers, the Dukes of Mar and Albany, of fine person and energetic tastes, interested in all the operations of war, fond of fine horses and gallant doings, and coming up to all the popular expectations of what was becoming in a prince. Nothing is more difficult to make out at any time than the real motives and meaning of family discords: and this is still more the case in an age not yet enlightened by the clear light of history. The chroniclers, especially Boece, have much doubt thrown upon them by more serious historians, who quote them and build upon them nevertheless, having really no better evidence to go upon. The report of these witnesses is that James had been warned by witches, in whom he believed, and by one Andrew the Fleming, an astrologer, that his chief danger arose from his own family, and that "the lion should be devoured by his whelps." Pitscottie's account, however, indicates a conspiracy between Cochrane and the Homes, whom Albany had mortally offended, as the cause at once of these prophecies and the King's alarm. The only thing clear is that he was afraid of his brothers, and considered their existence a danger to his life. It would appear that he had already begun to surround himself with those favourites to whom was attributed every evil thing in his reign, when this poison was first instilled into his mind: and the blame was attributed rightly or wrongly to Cochrane, the chief of his "minions," who very probably felt it to be to his interest to detach from James's side the manly and gallant brothers who were naturally his nearest counsellors and champions.

There is very little that is authentic known of the men whom James III thus elevated to the steps of his throne. Cochrane was an architect probably, though called a mason in his earlier career, and had no doubt been employed on some of the buildings in which the King delighted, being "verrie ingenious" and "cunning in that craft." Perhaps, however, to make the royal favour for a mere craftsman more respectable, according to the notions of the time, it is added in a popular story that the favourite was a man of great strength and stature, whose prowess in some brawl attracted the admiration of the timid monarch, to whom a man who was a tall fellow of his hands, as well as a person of similar tastes to himself, might well be a special object of approval. A musician, William Roger, an Englishman, whose voice had charmed the King—a weakness which at least was not ignoble, and was shared by various other members of his race—was the second of James's favourites: and there were others still less important—one the King's tailor—a band of persons of no condition, who surrounded him no doubt with flattery and adulation, since their promotion and maintenance were entirely dependent on his pleasure. King Louis XI was at that time upon the throne of France, a powerful prince whose little privy council was composed of equally mean men, and perhaps some reflection from the Court of the old ally of Scotland made young James believe that this was the best and wisest thing for a King to do. Louis was also a believer in astrologers, witches, and all the prophecies and omens in which they dealt. To copy him was not a high ambition, but he was in his way a great king, and it is conceivable that the feeble monarch of Scotland, never roused to the height of his father's or grandfather's example, took a little satisfaction in copying what he could from Louis. The example of Oliver le Dain might make him think that he showed his superiority by preferring his tailor, a man devoted to his service, to Albany or Angus. And if Louis trembled at the predictions of his Eastern sage, what more natural than that James should quake when the stars revealed a danger which every spaewife confirmed? No doubt he would know well the story of the mysterious spaewife who, had her advice been taken, might have saved James I. from his murderers. It is rarely that there is not a certain cruelty involved in selfish cowardice. In a sudden panic the mildest-seeming creature will trample down furiously any weaker being who stands in the way of his own safety, and James was ready for any atrocity when he was convinced that his brothers were a danger to his life and crown. The youngest, the handsome and gallant Mar, was killed by one treachery or another; and Alexander of Albany, the inheritor of that ill-omened title, was laid up in prison to be safe out of his brother's way.

We find ourselves entirely in the regions of romance in this unfortunate reign. Sir Walter Scott has painted for us the uncomfortable Court of Louis with his barber and his prophet, and Dumas has reproduced almost the identical story in his Vingt Ans Après, of the Duke of Albany's escape from Edinburgh. There could scarcely be a more curious scene. Strangely enough James himself was resident in the castle when his brother was a prisoner there. One would have thought that so near a neighbourhood would have seemed dangerous to the alarmed monarch, but perhaps he thought, on the other hand, that watch and ward would be kept more effectually under his own eyes. Mar had died in the Canongate, perhaps in the Tolbooth there, according to tradition in a bath, where he was bled to death, probably in order that a pretence of illness or accident might be alleged; and Edinburgh, no doubt, was full of dark whispers of this strange end of one prince, and the danger of the other, shut up within the castle walls where the King's minions had full sway, and any night might witness a second dark deed. Prince Alexander's friends must have been busy and eager without, while he was not so strictly under bar and bolt inside that he could not make merry with the castle officials now and then, and cheat an evening with pleasant talk and a glass of good wine with a young captain of the guard. One day there came to him an intimation of the arrival of a ship at Leith with wine from France, accompanied by some private token that there was more in this announcement than met the ear. Albany accordingly sent a trusted servant to order two flasks of the wine, in one of which, contained in a tube of wax, was enclosed a letter, in the other a rope by which to descend the castle walls. The whole story is exactly as Dumas tells the escape of the Duc de Beaufort, though whether the romancer could have seen the old records of Scotland, or if his legend is sanctioned by the authentic history of France, I am unable to tell. Alexander, like the prince in the novel, invited the Captain of the Guard to sup with him to try the new wine—an invitation gladly accepted. After supper the Captain "passed to the King's chamber to see what was doing, who was then lodged in the castle," probably to get the word for the night. It is curious to think of the unconscious officer, so little aware of what was about to befall, going from the chamber of the captive to that of the King, where the little Court would be assembled at their music or their "tables," or where perhaps James was taking counsel over the leafage of a capital or the spring of an arch—and thence returning when all the rounds were made, the great gates barred and bolted, the sentries set, to the Prince in his prison, who was a finer companion still. Alexander plied the unsuspecting Captain with his wine, spiced or perhaps drugged to make it act the sooner, and along with him a warder or two who were in constant attendance upon the royal prisoner. A prince to drink with such carles! "The fire was hett, and the wyne was strong": and the united influence of the spiced drink and the hot room soon overcame the revellers, all but Alexander and his trusty man, who had taken care to refrain. In Dumas the gaoler was but gagged and bound: but in Scotland life went for little, and some of the authorities say that when the Prince saw the drunkards in his power, "he lap from the board and strak the captane with ane whinger and slew him, and also stiked other two with his own hand." He had been informed that he was to die the next day if he did not escape that night, which was some excuse for him.[2] When the men were thus disposed of, in one way or another, the Prince and his servant, "his chamber chyld," stole out with the rope to "a quiet place" on the wall. Coming out into the dark freshness and stillness of the night after that stifling and horrible room, seeing the stars once more and the distant glimmer of the sea, and feeling freedom at hand, it was little they would reck of the gaolers, always an obnoxious class. One would imagine that it must have been on the most precipitous side of the castle rock where there were few sentinels and the exit was easy, though the descent terrible. The faithful servant tried the rope first but found it too short, and fell, breaking his thigh. With what feelings Alexander must have stolen back to get his sheets with which to lengthen the rope, pushing through the smoke, almost despairing to get off in safety! One is relieved to hear that he took his crippled attendant on his back and carried him, some say to a safe place—or, as others say, all the way across country to where the ship rocked at the pier of Leith. They must have got down to some dark spot on the northern slopes, where there would be no city watchman or late passer-by to give the alarm, and all would be clear and still before them to the water's edge—though a long, weary, and darkling way.

"But on the morne when the watchman perceived that the towis were hinging over the walls, then ran they to seek the Captane to show him the matter and manner, but he was not in his own chamber. Then they passed to the Duke's chamber and found the door open and ane dead man lying in the chamber door and the captane and the rest burning in the fire, which was very dollorous to them; and when they missed the Duke of Albanie and his chamber chyld, they ran speedilie and shewed the King how the matter had happened. But he would not give it credence till he passed himself and saw the matter."

These events happened in 1479, when Albany escaped to France, where he remained for some years. Up to this period all that is said of him has been favourable. His treatment by his brother was undeserved, and there is no sign of either treachery or rebellion in him in these early years. But when he had languished for a long time in France perhaps, notwithstanding a first favourable reception, sooner or later eating the exile's bitter bread—exasperation and despair must have so wrought in him that he began to traffic with the "auld enemy" of England, and even put his hand to a base treaty, by which his brother was to be dethroned and he himself succeed to the kingdom by grace of the English king—a stipulation which Albany must have well known would damn him for ever with his countrymen.

In the meantime James had begun to breathe again in the relief he felt to be freed of the presence of both his brothers. He "passed through all Scotland at his pleasure, in peace and rest," says the chronicler. But it was not long that a king of Scotland could be left in this repose. The usual trouble on the Borders had begun again as soon as Edward IV was secure upon his throne, and the English king had even sent his ships as far as the Firth of Forth, where he burnt villages and spoiled the coast under the very eyes of James. Though he would so much rather have been left in quiet to complete his beautiful new buildings at Stirling and arrange the choir in his new chapel, where there was a double supply of musicians that the King might never want this pleasure, yet the sufferings of the people and the angry impulse of the discontented nobles were more than James could resist, and he set forth reluctantly towards the Border to declare war. He had become more and more shut up within his little circle of favourites after the death and disappearance of his brothers, and Cochrane had gradually acquired a more and more complete sway over the mind of his master and the affairs of the realm. The favourite had been guilty of all those extravagances which constitute the Nemesis of upstarts. He had trafficked in patronage and promotion, he had debased the currency, and he was supposed to influence the King to everything least honourable and advantageous to the country. Last injury of all, he had either asked from the King or accepted from him—at least, permitted himself to be tricked out in the name of Mar, the title of the young prince whose death he was believed to have brought about. The lords of Scotland had already remonstrated with the King on various occasions as to the unworthy favourites who usurped their place around his throne: and their exasperation seems to have risen to a height beyond bearing when they found "the mason," as Cochrane is called, with his new liveries and extravagance of personal finery, at the head of the army which was raised to avenge the English invasion, and in the closest confidence of the King. When they had got as far as Lauder the great lords, who were left out of all James's private councils, assembled in a council of their own in the parish church to talk over their grievances, and to consult what could be done to reform this intolerable abuse and to bring back the King to the right way. Some, it would appear, went so far as to meditate deposition, declaring that James was no longer fit to be their King, having renounced their counsel and advice, banished one brother and slain another, and "maid up fallowes, maissones, to be lords and earls in the place of noblemen." The result of the meeting, however, was that milder counsels prevailed so far as James was concerned: "They concluded that the King should be taine softlie without harm of his bodie, and conveyed to the Castle of Edinburgh with certain gentlemen," while Cochrane and the rest were seized and hanged over Lauder Brig.

The question, however, remained, Who should be so bold as to take the first step and lay hands upon the favourite? It was now that Lord Gray, one of the conspirators, told, with that humour which comes in so grimly in many dark historic scenes, the story of the mice and the cat—how the mice conspired to save themselves by attaching a bell to the cat to warn them of her movements—until the terrible question arose which among them should attach to the neck of the enemy this instrument of safety. One can imagine the grave barons with half a smile looking at each other consciously, in acknowledgment of a risk which it needed a brave man to run. Angus, the head of the existing branch of the Douglas family, who had already risen into much of the power and importance of his forfeited kinsman, answered with equally grim brevity "I'se bell the cat." But while he spoke, the general enemy, mad with arrogance and self-confidence, and not believing in any power or boldness which could stop him in his career, forestalled the necessity. He came to the kirk, where no doubt he had heard there was some unauthorised assembly, arrayed in black velvet with bands of white, the livery he had chosen, a great gold chain round his neck, a hunting horn slung about him adorned with gold and jewels, and probably a marvel of mediæval art—and "rushed rudlie at the kirk door." The hum of fierce satisfaction which arose when the keeper of the door challenged the applicant for admission, and the answer, "The Earl of Mar," rang into the silence in which each man had been holding his breath, may be imagined. It was Archibald Bell-the-Cat, ever hereafter known by that name, who advanced to meet the swaggering intruder in all his pride of privilege and place, but with a welcome very different from that which the favourite expected, who had come, no doubt, to break up the whisperings of the conspirators and assert his own authority. Angus pulled the gold chain from Cochrane's neck, and said "a rop would sett him better," while another Douglas standing by snatched at the horn. Cochrane, astonished but not yet convinced that any real opposition was intended, asked between offence and alarm, perhaps beginning to doubt the sombre excited assembly, "My lords, is it jest or earnest?" It would seem that the grim and terrible event of the execution "over the Bridge of Lauder" though why this special locality was chosen we are not told, followed with an awful rapidity. The chief offender had fallen into the hands of the conspirators with such unhoped-for ease that they evidently felt no time was to be lost.

"Notwithstanding the lords held him quiet while they caused certain armed men pass to the King's pavilion, and two or three wyse men with them, and gave the King fair and pleasant words, till they had laid hands on all his servants, and took them and hanged them over the Bridge of Lauder before the King's eyes, and brought in the King himself to the council. Thereafter incontinent they brought out Cochrane and his hands bound with ane tow, behind his back, who desired them