CHAPTER I

A BURGHER POET

After the extraordinary climax of dramatic interest which brought the history of Edinburgh and of Scotland to the knowledge of the whole world, and which has continued ever since to form one of the most exciting chapters in general history, it was inevitable that when that fated Court dispersed, and the lady who was its charm and head disappeared also under the tragic waves which had been rising to engulf her, there should fall a sudden blank into the record, a chill of dulness and tedium, the charm departed and the story done. In fact, it was not at all so, and the metropolis of Scotland continued to seethe with contending elements, and to witness a continued struggle, emphasised by many a martyrdom and deed of blood, and many a desperate battle both hand to hand and head to head in the streets and in the council chambers, all with more or less the religious question involved, and all helping to work out the final settlement. When that final settlement came after all the tumults and blood it had cost, it is scarcely possible not to feel the downfall from those historical commotions to the dead level of a certain humdrum good attained, which was by no means the perfect state hoped for, yet which permitted peace and moderate comfort and the growth of national wellbeing. The little homely church towers of the Revolution, as they are to be seen, for instance, along the coast of Fife, are not more unlike the Gothic spires and pinnacles of the older ages, than was the limited rustical provision of the Kirk, its restricted standing and lowered pretensions, unlike the ideal of Knox, the theocracy of the Congregation and the Covenant. Denuded not only of the wealth of the old communion, but of those beautiful dwelling-places which the passion of the mob destroyed and which the policy of the Reformers did not do too much to preserve—deprived of the interest of that long struggle during which each contending presbyter had something of the halo of possible martyrdom about his head—the Church of the Revolution Settlement lost in her established safety, if not as much as she gained, yet something which it was not well to lose. And the kingdom in general dropped in something like the same way into a sort of prose of existence, with most of the picturesque and dramatic elements gone. Romance died out along with the actual or possible tragedies of public life, and Humour came in, in the development most opposed to romance, a humour full of mockery and jest, less tender than keen-sighted, picking out every false pretence with a sharp gibe and roar of laughter often rude enough, not much considerate of other people's feelings. Perhaps there was something in the sudden cessation of the tragic character which had always hitherto distinguished her history, which produced in Scotland this reign of rough wit and somewhat cynical, satirical, audacious mirth, and which in its turn helped the iconoclasts of the previous age, and originated that curious hatred of show, ceremony, and demonstration, which has become part of the Scottish character. The scathing sarcasm—unanswerable, yet false as well as true—which scorned the "little Saint Geilie," the sacred image, as a mere "painted bradd," came down to every detail of life; the rough jokes of the Parliament House at every trope as well as at every pretence of superior virtue; the grim disdain of the burgher for every rite; the rude criticism of the fields, which checked even family tendernesses and caresses as shows and pretences of a feeling which ought to be beyond the need of demonstration, were all connected one with another. Nowhere has love been more strong or devotion more absolute; but nowhere else, perhaps, has sentiment been so restrained, or the keen gleam of a neighbour's eye seeing through the possible too-much, held so strictly in check all exhibitions of feeling. Jeanie Deans, that impersonation of national character, would no more have greeted her delivered sister with a transport of kisses and rapture than she would have borne false testimony to save her. There is no evidence that this extreme self-restraint existed from the beginning of the national history, but rather everything to show that to pageants and fine sights, to dress and decoration, the Scots were as much addicted as their neighbours. But the natural pleasure in all such exhibitions would seem to have received a shock, with which the swift and summary overthrow of Mary's empire of beauty and gaiety, like the moral of a fable, had as much to do as the scornful destruction of religious image and altar. The succeeding generations indemnified themselves with a laugh and a gibe for the loss of that fair surface both of Church and Court: and the nation has never given up the keen criticism of every sham and seeming which exaggerated the absolutism of its natural character, and along with the destruction of false sentiment imposed a proud restraint and restriction upon much also that was true.

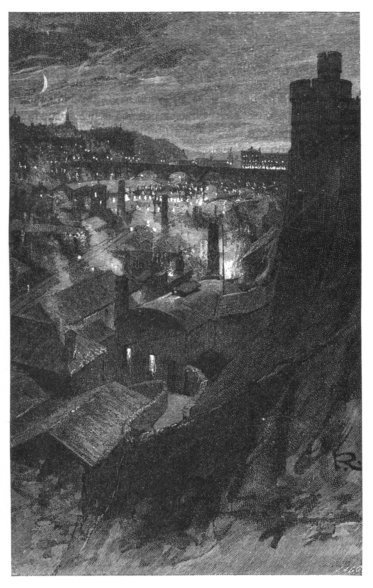

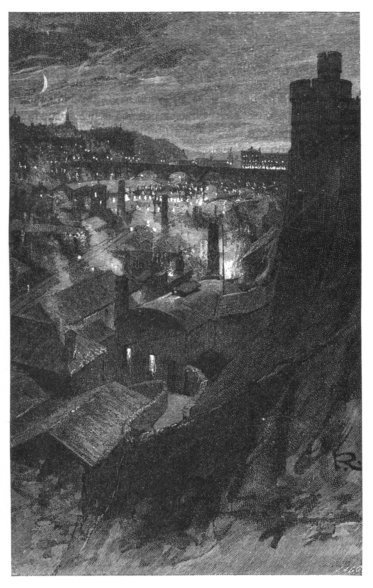

EDINBURGH: GENERAL VIEW

To come down from the age when Mary still reigned in Holyrood and Knox in St. Giles's—and Edinburgh saw every phase of passion and tragedy, wild love, hatred, revenge, and despair, with scarcely less impassioned devotion, zeal, and fury of Reformation, and all the clang of opposed factions, feuds, and frays in her streets—to the age when the Parliament House and its law courts were the centre of Edinburgh, when Holyrood was the debtors' sanctuary, and St. Giles's a cluster of parish churches, even its distinctive name no longer used: and when the citizens clustered about the Cross of afternoons no longer to see the heralds in their tabards and hear the royal proclamations, but to tell and spread the news from London and discuss the wars in the Low Countries, and many a witty scandal, gibes from the Bench and repartees from the Bar, the humours of the old lords and ladies in their "Lodging" in the Canongate, and the witticisms of the favourite changehouse—is as great a leap as if a whole world came between. The Court at St. Germains retained the devotion of many, but Anne Stewart was on the throne, and rebellion was not thought of, while everything was still full of hope for the old dynasty, so that Edinburgh was at full leisure to talk and jeer and gossip and make encounter of wits, with nothing more exciting in hand. In this tranquil period, his apprenticeship being finished, a certain young man from the west, by the name of Allan Ramsay, opened a shop in the High Street "opposite Niddry's Wynd" as a "weegmaker"—perhaps, if truth were known, a barber's shop, in all ages known as the centre of gossip wherever it appears. It is odd, by the way, that a place so entirely dedicated to the service of the male portion of the population, and where women have no place, should have this general reputation; but so it has always been. He had spent his early years as a shepherd on Crawford Moor in the Upper Ward of Clydesdale, and no doubt had there learned every song that floated about the country-side. "Honest Allan" was in every respect a model of the well-doing and prosperous Edinburgh shopkeeper of his time—a character not too entirely engrossed by business, always ready for a frolic, a song, a decorous bout of drinking, and known in all the haunts of the cheerful townsmen: tolerant in morals yet always respectable, fond of gossip, fond of fun, and if not fond of money yet judiciously disposed to gain as much as he could make, or as his apprentices and careful wife could make for him: and gradually progressing from a smaller to a larger shop, from a less to a more "genteel" business, and finally to a comfortable retirement.

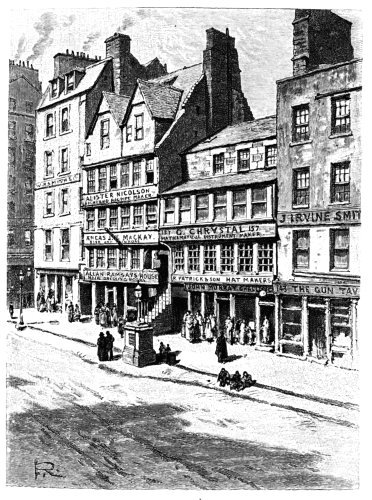

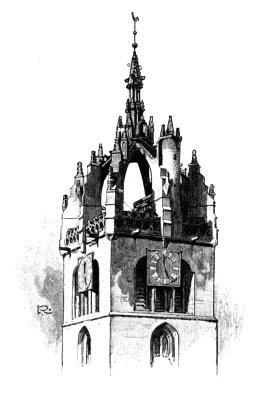

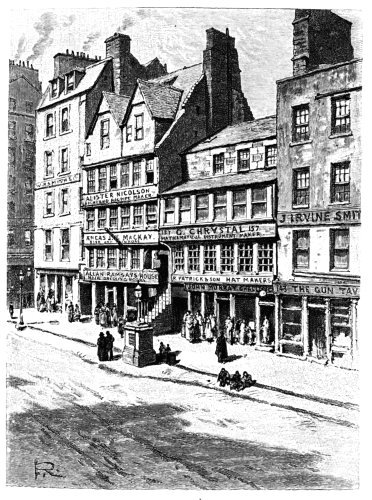

ALLAN RAMSAY'S SHOP

In such a life there was plenty of room for enjoyment, for relaxation, and no want of leisure to tell a good story or compose a string of couplets where that gift existed, even when most busy. We may imagine that he did not sit much at his block, but rather in the front of the shop amusing his customers, while their periwigs were curled or fitted, with Edinburgh gossip and wit in the familiarity of common citizenship, or with anecdotes which enlightened the country gentlemen, especially those from the west, the last bon mot of the Parliament House, or the Lord Advocate's latest deliverance. And his clubs were as numerous as those of a young man of fashion. The "Easy Club" was composed of "young anti-unionists," which indicates the politics which the wigmaker mildly held in cheerful subjection to the powers that were. No doubt he would have gone to the death (in verse) for the privileges of Edinburgh: but the anti-unionism or sentimental Jacobitism of his class was not of a kind to trouble any Government. And except the question of the Union, which was settled early in his career, politics do not seem to have been of an exciting character in Edinburgh. Local matters, always the most interesting of any to the inhabitants of a town not great enough to be cosmopolitan but full of distinct and striking individuality, furnished the poetical wigmaker with his first themes. It would seem that he only learned to rhyme from the necessity of taking his part in the high jinks of the club; at least all his early productions were intended for its diversion. An "Elegy on Maggie Johnstone," mistress of a convenient "public" at Morningside, then described as "a mile and a half west from Edinburgh," a suburb on "the south side," though now a part of the town—which would lie in the way of the members when they took their walks abroad, and no doubt formed the end of many a Sabbath day's ramble—was almost the first of his known productions; and we may well believe that the jovial shopkeepers were delighted with the sensation of possessing a poet of their own, and held many a discussion upon the new verses—brimful of local allusions and circumstances which everybody knew—over their ale as they rested in the village changehouse, or among the fumes of their punch in their evening assemblies. Verses warm from the poet's brain have a certain intoxicating quality akin to the toddy, and no doubt the citizens slapped their thighs and snapped their fingers with delight when some well-known name appeared, the incidents of some story they knew by heart, or the features of some familiar character. The satisfaction of finding in what they would call poetry a host of local allusions about which there was no ambiguity, which they understood like their ABC, would rouse the first hearers to noisy enthusiasm. And thus encouraged, the cheerful bard (as he was called in those days) went on till his fame penetrated beyond the club. Another elegy of a more serious description was so highly thought of that it was printed and given to the world by the club itself. That world meant Edinburgh, its many tradesmen, the crowded inhabitants of all the lofty "lands" about that centre of busy social life where the Cross still stood, and the old Tolbooth gloomed over the street, cut in two by its big bulk and the fabric of the Luckenbooths, a sort of island of masonry which divided what is now the broad and airy High Street opposite St. Giles's into two narrow straits. The writers and the advocates, the professors and the clergy, Councillor Pleydell and his kind, were not the first to discover that Ramsay the wigmaker had something in him more than the other rough wits of the shops and markets. And by and by the goodwives in their high lodgings, floor over floor, ever glad of something new, learnt to send one of the bairns with a penny to the wigmaker's shop in the afternoon to see if Allan Ramsay had printed a new poem: and received with rapture the damp broadsheet brought in fresh from the press, with a fable or a song in "gude braid Scots," or a witty letter to some answering rhymester full of local names and things. There was no evening paper in those days, and had there been it was very unlikely it would have penetrated into all the common stairs and crowded tenements. But Allan's songs, of which Jean or Peggy would "ken the tune," and the stories that would delight the bairns, were better worth the penny than news from distant London, which was altogether foreign and unknown to that humble audience.

This no doubt was the sort of fame and widespread popular appreciation which made the statesman of that day—was it Fletcher of Saltoun or Duncan Forbes the great Lord President?—bid who would make the laws so long as he might make the songs of the people. He had in all likelihood learnt Allan's widely flying, largely read verses, which every gamin of the streets knew by heart, in his childhood. And though they might not be in general of a very ennobling quality, there are glimpses of a higher poetry to come in some of these productions, and a great deal of cheerful self-assertive content and local patriotism, as well as of rough fun and jest. If it were not for the very unnecessary introduction of Apollo as the god to whom "the bard" addresses his wishes, there would be something not unworthy of Burns in the following lines. The poet has of course introduced first, as a needful contrast, "the master o' a guid estate that can ilk thing afford," and who is much "dawted (petted) by the gods"—

"For me, I can be weel content

To eat my bannock on the bent,

And kitchen't wi' fresh air;

O' lang-kail I can make a feast

And cantily haud up my crest,

And laugh at dishes rare.

Nought frae Apollo I demand,

But through a lengthened life,

My outer fabric firm may stand,

And saul clear without strife.

May he then, but gi'e then,

Those blessings for my share;

I'll fairly, and squarely,

Quit a', and seek nae mair."

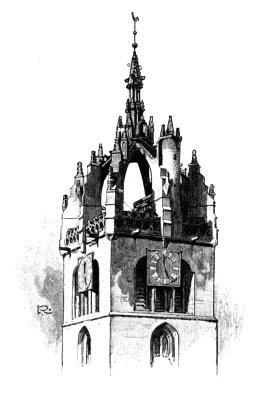

It was no doubt after he had achieved this reputation of the streets—a thing more difficult than greater fame—that his imagination developed in more continuous and refined effort. Whether he himself printed his penny broadsheet as well as sold it we are not informed, but as he began after a while to combine bookselling with wigmaking we may be allowed to imagine that the press which produced these flying leaves was either in or near his shop. It is difficult to realise the swarming of life and inhabitation within the high houses of the old town in an age when comfort was little understood: and even the concentration within so small a space, of business, work, interest, idleness, and pleasure, is hard to comprehend by people who have been used to appropriate a separate centre to each of the great occupations or exercises of mankind. When London was comparatively a small town it had still its professional distinctions—the Court, the Temple, the City, the place where law was administered and where money was made, where society had its abode and poverty found a shelter. But in old Edinburgh all were piled one on the top of another—the Parliament House within sight of the shops, the great official and the poor artificer under the same roof: and round that historical spot over which St. Giles's crown rose like the standard of the city, the whole community crowded, stalls and booths of every kind encumbering the street, while special pleaders and learned judges picked their steps in their dainty buckled shoes through the mud and refuse of the most crowded noisy market-place, and all the great personages of Edinburgh paced the "plainstanes" close by at certain hours, unheeding either smell or garbage or the resounding cries of the street.

CROWN OF ST. GILES'S

In such a crowded centre the sheets that were being read so eagerly, laughed over by the very cadgers at their booths, conned by the women at the stairheads, lying on every counter, where Allan's new verses would be pulled to pieces by brother wits who had known him to do better, or heard a livelier witticism from his lips no farther gone than yestreen, must very soon have come to the notice of the westland lads at the college, and from them to the learned professors, and still more directly to the lively groups that went and came to the Parliament House. Already the wigmaker's shop had thriven and prospered; the little man, short and fat and jovial, who had begun to lay out books in his window under the shadow of the curled and powdered periwigs, found the results of his double traffic more satisfactory than poets use. He boasts in one of his rhymed addresses that he thatches the outside and lines the inside of many a douce citizen, "and baithways gathers in the cash." He adds—

"And fain would prove to ilka Scot,

That poortith's no the poet's lot."

It must have been altogether an odd little establishment—the wigs set out upon their blocks, perhaps, who knows, the barber's humbler craft being plied behind backs; the books multiplying daily on shelves and in windows, and the ragged boys with their pennies waiting to see if there was a new piece by Allan Ramsay; while perhaps in the corner, where lay the lists of the new circulating library—the first in Scotland—Miss Lydia Languish with her maid, or my lady's gentlewoman from some fine house in the Canongate, had come in to ask for the last new novel from London, the Scotch capital having not yet begun to produce that article for itself.

One may be sure that Allan, rotund and smiling, was always ready for a crack with the ladies, and to recommend the brand new Pamela, the support of virtue, or some contemporary work of lesser genius. Though the general costume was like that worn in the other parts of the island, perhaps a little behind London fashions, the fair visitors would still be veiled with the plaid, the fine woven screen of varied tartan which covered the head like a hood, and could on occasion conceal the face more effectually than Spanish lace or Indian muslin—a singular peculiarity not ancient and scarcely to be called national, since the tartan came from the still-despised Highlands, and these were Lowland ladies who wore the plaid. This fashion would seem to have begun to be shaken by Ramsay's time, for he pleads its cause with all the fervour of a poetical advocate. There is something grotesque in the arguments, and still more grotesque in the names by which he distinguishes the wearers of the plaid.

"Light as the pinions of the airy fry

Of larks and linnets who traverse the sky,

Is the Tartana, spun so very fine

Its weight can never make the fair repine;

Nor does it move beyond its proper sphere,

But lets the gown in all its shape appear;

Nor is the straightness of her waist denied

To be by every ravished eye surveyed;

For this the hoop may stand at largest bend,

It comes not nigh, nor can its weight offend.

* * * * *

"If shining red Campbella's cheeks adorn,

Our fancies straight conceive the blushing morn,

Beneath whose dawn the sun of beauty lies,

Nor need we light but from Campbella's eyes.

If lined with green Stuarta's plaid we view,

Or thine, Ramseia, edged around with blue,

One shews the spring when nature is most kind,

The other heaven whose spangles lift the mind."

The description of the manner in which this engaging garment is worn has all the more reason to be quoted that it was not only a new piece by Allan Ramsay, but affords a glimpse of the feminine figures that were to be seen in the High Street of Edinburgh going to kirk and market in the beginning of the eighteenth century. There is, too, a pleasant touch of individuality in the musical street cry that wakes the morn.

"From when the cock proclaims the rising day,

And milkmaids sing around sweet curds and whey,

Till grey-eyed twilight, harbinger of night,

Pursues o'er silver mountains sinking light,

I can unwearied from my casements view

The Plaid, with something still about it new.

How are we pleased when, with a handsome air,

We see Hepburna walk with easy care!

One arm half circles round her slender waist,

The other like an ivory pillar placed,

To hold her plaid around her modest face,

Which saves her blushes with the gayest grace;

If in white kids her slender fingers move,

Or, unconfined, jet through the sable glove.

"With what a pretty action Keitha holds

Her plaid, and varies oft its airy folds!

How does that naked space the spirits move,

Between the ruffled lawn and envious glove!

We by the sample, though no more be seen,

Imagine all that's fair within the screen.

"Thus belles in plaids veil and display their charms,

The love-sick youth thus bright Humea warms,

And with her graceful mien her rivals all alarms."

The fair Hepburna, Humea, Campbella, and the rest may tempt the reader to a smile; but the picture has its value, and is a detail of importance in the realisation of that animated and crowded scene. By this time probably Ramsay had removed his shop to the end of the Luckenbooths, which faced "east" to the unencumbered portion of the High Street, where the City Cross stood, and where all the notable persons made their daily promenade. It was here that he was visited by a kindred spirit, the poet Gay, who had been brought to Edinburgh by his patroness the Duchess of Queensberry, and soon formed acquaintance with the local poet. The two little roundabout bards used to stand together at the door of the shop to watch the crowd, in which no doubt Ramsay would be gratified by a friendly nod from the Lord President, and swell with civic and with personal pride to point out to the English visitor that distinguished Scotsman the loyal and the learned Forbes. The Cross, round which this genteel and witty crowd assembled daily, stood then, according to the plans of the period, in the centre of the High Street, where it had been removed for the advantage of greater space in the previous century. And the view from Ramsay's shop—from which by this time the wigs had entirely disappeared, and which was now a refined and cultured bookseller's, adorned outside with medallions of two poets, Scotch and English, Ben Jonson and Drummond of Hawthornden—was bounded by the gate of the Netherbow with its picturesque tower, and glimpses through the open roadway, of the Canongate beyond, and the cross lines of busy traffic leading to Leith. It was thus a wide space between the lines of high houses, more like a Place than a street, upon which the two gossips gazed, no doubt with a complacent thought that their living presence underneath carried out the symbol of the two heads above—the poets of England and of Scotland—and that in the teeming street below them were many who pointed out to each other this new and delightful combination. They were not great poets, either of these round, fat, oily men of verse. And yet the association was pleasant. Perhaps the duchess's coach-and-six, in which the English bard had been conveyed from London, might drive through the open port, as the two stood delighted, watching the pedestrians hurry out of the way and the great lawyers and officials preparing to pay their devoirs to her Grace as she drew up before the bookshop. No doubt they thought it a scene to be remembered in the history of letters. She was at Penicuik House on a visit to the Clerks, who were friends and patrons of Allan, and no doubt had supped or drunk a dish of tea at New Hall, where the Lord President (who was only the Lord Advocate in those days) often took his case in his cousin's house, where Ramsay was a familiar and frequent guest. When Allan made wigs no longer, when all his occupations were about books, and everybody in Edinburgh, gentle and simple, knew him as the poet, he would be still more free to make his jokes and his compliments to all those fine people. But at no time was the genial little poet "blate," as he would himself have said. There was no shyness in him. He "braw'd it," as he says, with no doubt the finest of periwigs, long before he had ceased to be a skull-thatcher, and swaggered through the wynds and about the Cross with the best. The Edinburgh shopkeeper has never been "blate." He has always maintained a freedom of independence which has nothing of the obsequiousness of more common traders, and which gave the greater value to the sly compliment which he would insinuate between two jests. No doubt Campbella and Hamilla would laugh at the little man's compliments, his bows and admiring glances, yet would not object to his exposition of the tartan screen, the delicate silken plaid under which they shielded their radiant complexions and golden locks.

Allan must have seen many curious sights from those windows. The riding of the Parliament, when in gallant order two by two—the commissioners of the boroughs and the counties leading the way, the peers following, through the guards on either side who lined the streets—they rode up solemnly from Holyrood to the Parliament House, with crown and sword and sceptre borne before them, the old insignia, without which the Acts of the ancient Parliaments of Scotland were not considered valid—marching for the last time to their place of meeting to give up their trust—would be one of the most remarkable. The commoners had each two lackeys to attend him, the barons three, the earls four, a blue-coated brigade, relic of the old days when no gentleman moved abroad without a following; and Lyon King-at-arms in his finery to direct the line. With lamentation and humiliation was the session closed; even wise men who upheld the Union consenting to the general pang with which the last Scots Parliament went its way. And the glare of the fire must have lighted up the poet's rooms, and angry sparks fallen, and hoarse roar of voices drowned all domestic sounds, when the Porteous Mob turned Edinburgh streets into a fierce scene of tragedy for one exciting night. It would be vain indeed to describe again what Scott has set before us in the most vivid brilliant narrative. Such a scene breaking into the burgher quietude—the decent households which had all retired into decorous darkness for the night waking up again with lights flitting from story to story, the axes crashing against the doors of the Tolbooth, the wild procession whirling down the tortuous gloom of the West Bow—was such an interruption of monotonous life as few towns in the eighteenth century could have equalled; and it is curious to remember the intense national feeling and keen patriotic understanding of how far the populace would or could endure interference, which made Duncan Forbes in his place in Parliament stand up as almost the defender of that wild outburst of lawlessness, and John of Argyle turn from the royal presence to prepare his hounds, as he said, against the Queen's threat of turning the rebellious country into a desert. These proud Scotsmen had supported the Union: they had perceived its necessity and its use: but there was a point at which all their susceptibilities took fire, and Whig lords and politicians were at one with every high-handed Tory of the early times.

Allan Ramsay must also have seen, though he says nothing of it, the brief occupation of Edinburgh by the unfortunate Prince Charles Edward, and at a distance the pathetic little Court in Holyrood, the Jacobite ladies in their brief glory, the fated captains of that wild little army, in which the old world of tradition and romance made its last outbreak upon modern prose and the possibilities of life. One would imagine that for a man who had lived through that episode in the heart of the old kingdom of the Stewarts, and whose house lay half-way between the artillery of the castle, where a hostile garrison sat grimly watching the invaders below, and the camp at Holyrood—there would have been nothing in his life so exciting, nothing of which the record would have been more distinct. But human nature, which has so many eccentricities, is in nothing so wonderful as this, that the most remarkable historical scenes make no impression upon its profound everyday calm, and are less important to memory than the smallest individual incident. The swarm of the wild Highlanders that took sudden possession of street and changehouse, the boom of the cannon overhead vainly attempting to disperse a group here and there or kill a rebel, and the consciousness which one would think must have thrilled through the very air, that under those turrets in the valley was the most interesting young adventurer of modern times, the heir of the ancient Scots kings, their undoubted representative—how could these things fail to affect the mind even of the most steady-going citizen? But they did, though we cannot comprehend it. Allan has a word for every little domestic event in town or suburbs, but there is not a syllable said either by himself or his biographers to intimate that he knew what was going on under his eyes at that brief and sudden moment, the "one crowded hour of glorious life," which cost so much blood of brave men, and which the hapless Prince paid for afterwards in the disenchanted tedium of many a dreary year.

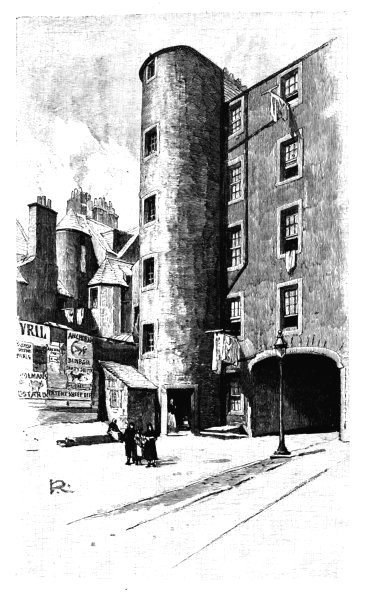

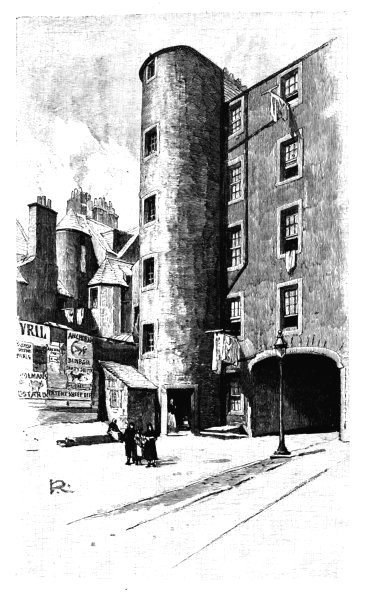

SMOLLETT'S HOUSE

It was before this time, however, that Ramsay reached the height of his fame and of his productions in The Gentle Shepherd. He had written some years before "A Pastoral Dialogue between Patie and Roger," published as usual in a sheet for a penny, and no doubt affording much pleasure to the great popular audience to whom the "new piece" was as the daily feuilleton, that friendly dole of fiction which sweetens existence. It was evidently so successful that after a while the poet composed a pendant—a dialogue between Jenny and Peggy. These two fragments pleased the fancy of both the learned and the simple, and no doubt called forth many a flattering inquiry after the two rustic pairs and demands for the rest of their simple history, which inspired the author to weave the lovers into the web of a continuous story, adding the rural background, so fresh and true to nature, and the rustic and humorous characters which were wanted for the perfection of the pastoral drama. Few poems ever have attained so great and so immediate a success. It went from end to end of Scotland, everywhere welcomed, read, conned over, got by heart. Such a fame would be indeed worth living for. The fat little citizen in his shop became at once the poet of his country, as he had been of the Edinburgh streets. It was nearly two centuries since Dunbar and Davie Lyndsay had celebrated their romantic town: and though the name of the latter was still a household word ("You'll no find that in Davie Lyndsay" being the popular scornful dismissal of any incredible tale), yet their works had fallen into forgetfulness. The new poet w