CHAPTER II

THE GUEST OF EDINBURGH

Royal Edinburgh, the city of the Scots kings and Parliament, the capital of the ancient kingdom, would seem to have become weary somewhere in the eighteenth century of dwelling alone upon her rock. There were, to be sure, reasons more prosaic for the construction of the New Town, the partner and companion of the old historical city. The population had increased, the desire for comfort and space, and many luxuries unknown to the early citizens of Edinburgh, had developed among the new. It was no longer agreeable to the lawyers and philosophers to be crowded up with the other inhabitants of a common stair, to have the din of street cries and commotion ever in their ears, and the lowest of the population always about their feet, as was inevitable when gentle and simple were piled together in the High Street and Canongate. The old houses might be noble houses when they were finally got at, through many drawbacks and abominations—though in those days there was little appreciation even of the stately beauty of old masonry and ornament—but their surroundings became daily more and more intolerable. And it was an anachronism to coop up a learned, elegant, and refined class, living under the Hanoverian Georges in peace and loyalty, within the circle of walls now broken down and useless, which had been adapted to protect the subjects of the old Scottish Jameses from continual attacks.

Happily the nature of the situation prevented any amalgamation or loss of the old boundaries and picturesque features of the ancient city, in the new. There was no question of continuation or enlargement. Another Edinburgh rose at the feet of the first, a sober, respectable, modern, and square-toed town, with wide streets and buildings solid and strong, not without pretensions to a certain stateliness of size and design, but in strong contrast with the architecture and fashion native to the soil—the high gables and turreted stairs of the past. The old town had to throw a drawbridge, permanent and massive, over the hollow at her feet before she could even reach the terraced valley on which the first lines of habitation were drawn, and which, rounding over its steep slope, descended towards another and yet another terrace before it stood complete, a new-born partner and companion in life of the former capital, lavish in space as the other was confined, leisurely and serious as the other was animated—a new town of great houses, of big churches—dull, as only the eighteenth century was capable of making them—of comfort and sober wealth and intellectual progress. The architects who adorned the Modern Athens with Roman domes and Greek temples, and placid fictitious ruins on the breezy hill which possessed a fatal likeness to the Acropolis, would have scoffed at the idea of finding models in the erections of the fourteenth century—that so-called dark age—or recognising a superior harmony and fitness in native principles of construction.

Yet though the public taste has now returned more or less intelligently to the earlier canons, it would be foolish not to recognise that there is a certain advantage even in the difference of the new town from the old. It is not the historical Edinburgh, the fierce, tumultuous, mediæval city, the stern but not more quiet capital of the Reformers, the noisy, dirty, whimsical, mirth-loving town, full of broad jest and witty epigram, of the eighteenth century. The new town has a character of its own. It is the modern, not supplanting or effacing, but standing by the old. Those who built it considered it an extraordinary improvement upon all that Gothic antiquity had framed. They were far more proud of these broad streets and massive houses than of anything their fathers had left to them, and flung down without remorse a great deal of the antiquated building after which it is now the fashion to inquire with so much regret. Notwithstanding the change of taste since that time, the New Town of Edinburgh still regards the old with a little condescension and patronage; but there is no opposition between the two. They stand by each other in a curious peacefulness of union, each with a certain independence yet mutual reliance. London and Paris have rubbed off all their old angles and made themselves, notwithstanding the existence of Gothic corners here and there, all modern, to the extinction of most of the characteristic features of their former living. But happy peculiarities of situation have saved our northern capital from any such self-obliteration. Edinburgh has been fortunate enough to preserve both sides—the ancient picturesque grace, the modern comfort and ease. And though Mr. Ruskin has spoken very severely of the new town, we will not throw a stone at a place so well adapted to the necessities of modern life. Those bland fronts of polished stone would have been more kindly and more congenial to the soil had they cut the air with high-stepped gables and encased their stairs in the rounded turrets which give a simple distinctive character to so many Scottish houses; and a little colour, whether of the brick which Scotch builders despise or the delightful washes[6] which their forefathers loved, would be a godsend even now. But still, for a sober domestic partner, the new town is no ill companion to the ancient city on the hill.

This adjunct to the elder Edinburgh had come into being between the time when Allan Ramsay's career ended in the octagon house on the Castle Hill, and another poet, very different from Ramsay, appeared in the Scotch capital. In the meantime many persons of note had left the old town and migrated towards the new. The old gentry of whom so many stories have been told, especially those old ladies who held a little court, like Mrs. Bethune Balliol, or made their bold criticism of all things both new and old, like those who flourish in Lord Cockburn's lively pages—continued to live in the ancestral houses which still kept their old-fashioned perfection within, though they had to be approached through all the squalor and misery which had already found refuge outside in the desecrated Canongate; but society in the Scotch metropolis was now rapidly tending across the lately erected bridge towards the new great houses which contemplated old Edinburgh across the little valley, where the Nor' Loch glimmered no longer and where fields lay green where marsh and water had been. The North Bridge was a noble structure, and the newly-built Register House at the other end one of the finest buildings of modern times to the admiring chroniclers of Edinburgh. And the historians and philosophers, the great doctors, the great lawyers, the elegant critics, for whom it was more and more necessary that the ways of access between the old town and the new might be made more easy, presided over and criticised all those wonderful new buildings of classic style and unbroken regularity, and watched the progress of the Earthen Mound, a bold and picturesque expedient which filled up the hollow and made a winding walk between, with interest as warm as that which they took in the lectures and students, the books and researches, which were making their city one of the intellectual centres of the world.

This is a position to which Scotland has always aspired, and the pride of the ambitious city and country was never more fully satisfied than in the end of last and the beginning of the present century. Edinburgh had never been so rich in the literary element, and the band of young men full of genius and high spirit who were to advance her still one step farther to the climax of fame in that particular, were growing up to take the places of their fathers. A place in which Walter Scott was just emerging from his delightful childhood, in which Jeffrey was a mischievous boy and Henry Brougham a child, could not but be overflowing with hope, especially when we remember all the good company there already—Dugald Stewart, bringing so many fine young gentlemen from England to wonder at the little Scotch capital, and a crowd of Erskines, Hunters, Gregories, Monroes, and Dr. Blair and Dr. Blacklock, and the Man of Feeling—not to speak of those wild and witty old ladies in the Canongate, and the duchesses who still recognised the claims of Edinburgh in its season. To all this excellent company, whose fame and whose talk hung about both the old Edinburgh and the new like the smoke over their roofs, there arrived one spring day a wonderful visitor, in appearance like nothing so much as an honest hill farmer, travelling on foot, his robust shoulders a little bowed with the habit of the plough, his eyes shining, as no other eyes in Scotland shone, with youth and genius and hope. He knew nobody in Edinburgh save an Ayrshire lad like himself, like what everybody up to this time had supposed Robert Burns to be. The difference was that the stranger a little while before had put forth by the aid of a country printer at Kilmarnock a little volume of rustic poetry upon the most unambitious subjects, in Westland Scotch, the record of a ploughman's loves and frolics and thoughts. It is something to know that these credentials were enough to rouse the whole of that witty, learned, clever, and all-discerning community, and that this visitor from the hills and fields in a moment found every door opened to him, and Modern Athens, never unconscious of its own superiority and at this moment more deeply aware than usual that it was one of the lights of the earth, at his feet.

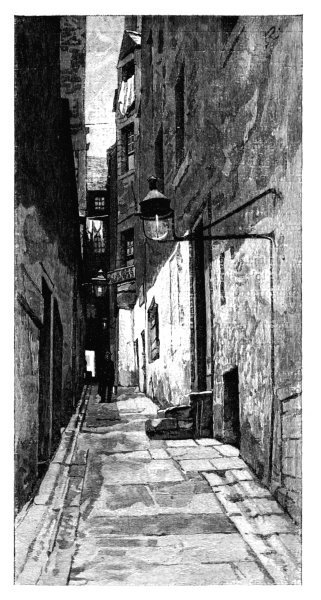

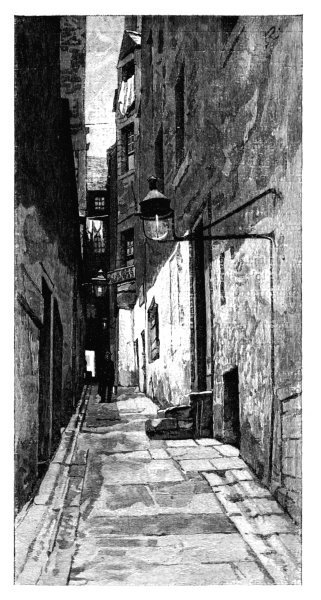

LADY STAIR'S CLOSE

Burns was but a visitor, the lion of a season, and therefore we are not called upon to associate with Edinburgh the whole tragic story of his life. And yet his appearance was one of the most remarkable that has distinguished the ancient town. He arrived among all the professors, the men of letters, the cultured classes who held an almost ideal pre-eminence, more like what a young author hopes than is generally to be met with among men—his heart beating with a sense of the great venture on which he was bound, and a proud determination to quit himself like a man whatever were the magnitudes among which he should have to stand. Mere Society so called, with all its bustle of gaiety and endless occupation about nothing, might have exercised upon him something of the fascination which fine names and fine houses and the sweep and whirl of hurried life certainly possess; but he who expresses almost with bitterness his disgust to see a blockhead of rank received by one of his noble patrons with as much, nay more, consideration than is given to himself, would probably have had very little toleration for the butterflies of fashion: whereas Edinburgh society impressed him greatly, as of that ideal kind of which the young and inexperienced dream, where the best and brightest are at the head of everything, where poetry is a passport to the innermost sanctuary and conversation is like the talk of the gods. They were all distinguished for one literary gift or grace or another, philosophers golden-mouthed, poets of the most polished sort: their knowledge, their culture, their intellectual powers, were the foundation upon which their little world was built. The great people who were to be found among them were proud to know these scholars and sages—it was they, and not an occasional family of rank, or still more rare man of wealth, who gave character and meaning to Edinburgh. To be received in such society was the highest privilege which a young poet could desire; and it was worthy to receive and foster and encourage that new light that came from heaven.

On their side the heads of society in Edinburgh were much interested in this young man. There had been an article in the Lounger, fondly deemed a Scotch Spectator, an elegant literary paper widely read not only in Scotland but even beyond the Border, upon him and his works. "The Ayrshire Ploughman" was the title of the article, and it set forth all the imperfections of his breeding, his want of education, his ignorance both of books and of the world, and yet the amazing verses he had produced, which, though disguised in a dialect supposed to be unknown to the elegant reader, and for which Henry Mackenzie, the Man of Feeling, supplied a glossary—living, he himself, in an old-fashioned house in the South Back of the Canongate and within the easiest reach of those wonderful old ladies who spoke broad Scotch, and left no one in any doubt as to the strong opinions expressed therein—were certified to be worthy the perusal of the most fastidious critic. Lord Monboddo, who was the author of speculations which forestalled Darwin and who considered a tail to be an appendage of which men had not long got rid, on the one side, and the metaphysicians and philosophers on the other, would no doubt prick up their ears to hear of this absolutely new being in whom there might be seen some traces of primeval man. We forget which of the early Jameses it was who is said to have shut up two infants with a dumb nurse in one of the islands of the Firth to ascertain what kind of language they would speak when thus left to the teaching of nature. The experiment was triumphantly successful, for the heaven-taught babies babbled, the chroniclers tell us, a kind of Hebrew, thus proving beyond doubt that the language of the Old Testament was the original tongue of man. The Edinburgh savants must have received Burns with something of the same feeling: for here was a new soul which had been shut up amid the primeval elements, and the language it spoke was Poetry! yet poetry disguised in imperfect dialect which might yet be trained and educated into elegance. They asked him to dinner as a first step, and gathered round him to hear what he would have to say; to observe the effect produced by the sight of learning, criticism, knowledge; to enjoy his awe, and note the improvement that could not but ensue. This curiosity was full of kindness; their hearts were a little touched by the ploughman, by his glowing eyes, and by the strange sight of him there among them in the midst of their high civilisation, a rustic clown who knew nothing better than a thatched cottage and a clay floor. No doubt they had the sincerest desire that he should be made to understand how much he was deficient, what a great deal he had to learn, and be taught to use fine language, and turn his attention to higher subjects, and be altogether elevated and brought on in the world. The situation is very curious and full of human interest, even had the stranger been less in importance than he was. It is wonderfully enlightening in any circumstances to see such an encounter from both sides, to perceive the light in which it appears to them, and the very different light in which it is seen by him. There was the usual great divergence between the views of the visitor and the highly-cultured community to which he came. For he indeed did not come there at all to be enlightened and trained and put in the way he should go. He came full of delightful hope that he was coming among his own kind, that he was for the first time to meet his own species, and recognise in other human faces the light that shone about his own path, but in none of the other muddy ways of the country-side; to make friends with his natural brethren, and be understood of them as no one yet had been found to understand him. In his high anticipations, in his warm enthusiasm of hope, he himself figured dimly as a sort of noble exile coming back to his father's house. So does every child of fancy regard the world of which he knows nothing, the world of the great and famous, where to dazzled fancy all the beautiful things, words, and thoughts for which he has been sighing all his life are to be found.

They met, and they were, if not mutually disappointed, yet strangely astonished and perplexed. Burns would seem to have been always on his guard, too much on his guard we should be disposed to say, suspicious of the intention to guide, to chasten, to educate and refine, which was indeed in the kindest way at the bottom of everybody's thoughts. He was determined to be astonished by nothing, to keep his head so that no one should ever be able to say that it was turned by his new experiences—an attitude which altogether bewildered the good people, who were willing to give him every kind of education, to excuse any rudeness or roughness or imperfection, but not to see a man at his ease, appearing among them as if he were of them, requiring no allowance to be made for him, holding his head high as any man he met. All the accounts we have of his appearance in Edinburgh agree in this. He was neither abashed nor embarrassed; no rustic presumption or vulgarity, but quite as little any timidity or awkwardness, was in the Ayrshire ploughman. His shoulders a little bent with the work to which he had been accustomed, his dress like a countryman, a rougher cloth perhaps, a pair of good woollen stockings rig and fur, his mother's knitting, instead of the silk which covered limbs probably not half so robust—but so far as manners went, nothing to apologise for or smile at. The accounts all agree in this. If he never put himself forward too much, he never withdrew with any unworthy shyness from his modest share in the conversation. Sometimes he would be roused to eloquent speech, and then the admiring ladies said he carried them "off their feet" in the contagion of his enthusiasm and emotion. But this was a very strange phenomenon for the Edinburgh professors and men of letters to deal with: a novice who had not come humbly to be taught, but one who had come to take up his share of the inheritance, to sit down among the great, as in his natural place. He was not perhaps altogether unmoved by their insane advices to him, one of the greatest of lyrical poets, a singer above all—to write a tragedy, to give up the language he knew and write his poetry in the high English which, alas! he uses in his letters. Not unmoved, and seriously inclining to a more lofty measure, he compounded addresses to Edinburgh:

"Edina, Scotia's darling seat!"

and other such intolerable effusions. One can imagine him roaming through the fields between the old town and the new, and looking up to the "rude rough fortress," and on the other side to the brand-new regular lines of building, where

"Architecture's noble pride

Bids elegance and splendour rise,"

and musing in his mind how to celebrate them in polished verse so that even the critics may be satisfied—

"Thy sons, Edina! social, kind,

With open arms the stranger hail;

Their views enlarged, their liberal mind,

Above the narrow, rural vale;

Attentive still to sorrow's wail,

Or modest merit's silent claim;

And never may their sources fail!

And never envy blot their name!"

One wonders what the gentlemen said to this in the old town and the new—whether it did not confuse them still further, as well intended perhaps, but not after all like the "Epistle to Davie," though they had all advised him to amend that rustic style. A very confusing business altogether—difficult for the kind advisers as well as for the poet, and with no outlet that any one could see.

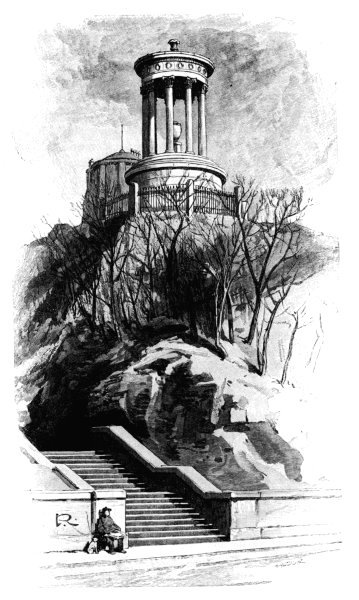

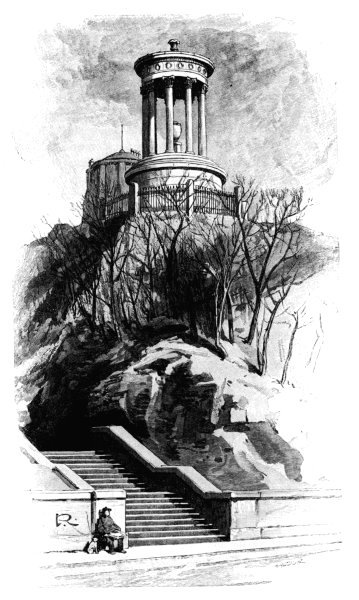

DUGALD STEWART'S MONUMENT

We have, however, a more agreeable picture of the visitor on another occasion when he walked out into the country with Dugald Stewart in a spring morning to the hills of Braid and talked that gentle philosopher's heart away, not now about Edina's palaces and towers. "He told me ... that the sight of so many smoking cottages gave a pleasure to his mind which none could understand who had not witnessed like himself the happiness and worth which they contained." It is more pleasant to think of the poet's dark eyes lighting up as he said this than to watch him proud and self-possessed in the drawing-rooms holding his own, taking such good care that nobody should divine how his heart was beating and his nerves athrill.

But after all there is no such account given of this wonderful visitor to Edinburgh as that we have from the after-recollections of a certain "lameter" boy who was once present in a house where Burns was a guest. The Scott boys from George Square had been admitted to the party which they were too young to join in an ordinary way, in order that they might see this wonder of the world, the ploughman-poet who was not afraid, but behaved as well as any of the gentlemen. And it befell by the happiest chance that Burns inquired who was the author of certain verses inscribed upon a print which he had been looking at. No one knew but young Walter, who we may be sure had not lost a look or a word of the stranger, and who had read everything in his invalid childhood. The boy was not bold enough to answer the question loud out, but he whispered it to some older friend, who told the poet, no doubt with an indication of the blushing and eager lad from whom it came, which procured him a word and a look never forgotten. But there passed at the same time a thought through young Walter's mind, the swift reflection of that never-failing criticism of youth which pierces unaware through all wrappings and veils of the soul. "I remember I thought Burns's acquaintance with English poetry was rather limited; and also that having twenty times the ability of Allan Ramsay and of Fergusson, he talked of them with too much humility as his models." The much-read boy was a little shocked, no doubt disturbed in his secret soul that the poet—so far above any other poet that was to be seen about the world in those days—should not have known that verse: though indeed men better read than Burns might have been excused for their want of acquaintance with a minor poet like Langhorne; but how true was the indignant observation, half angry, that with "twenty times the ability" it was Allan Ramsay and the still less important unfortunate young Fergusson to whom Burns looked up! Did the boy wonder perhaps, though too loyal to say it—for criticism at his age is always keen—whether there might be a something not quite real in that devotion, and ask in the recesses of his mind whether it was possible for such a man to be so self-deceived?

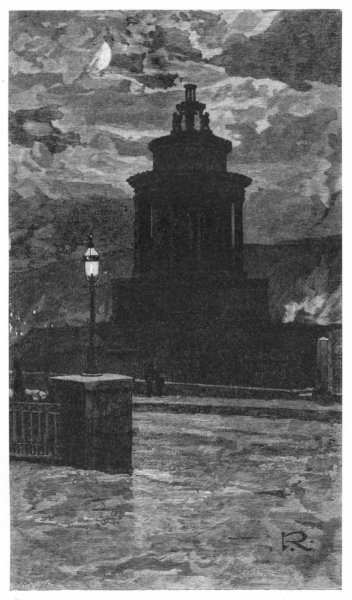

There were no doubt various affectations about Burns, as when he talks big in his diary of observing character and finding this pursuit the greatest entertainment of his life in Edinburgh, with a pretension very general among half-educated persons: but there is no reason to believe that he was not quite genuine about his predecessors. A poet is not necessarily a critic; and Allan Ramsay's fame had been exactly of the popular kind which would attract a son of the soil, whereas Fergusson was the object of Burns's especial tenderness, pity, and regard. And it is touching to recollect that the only sign he left of himself in Edinburgh, where for the first time he learned what it was to mix in fine company and to feel the freedom of money in his pocket, from which he could afford a luxury, was to place a stone over the grave of Fergusson in the Canongate Churchyard, where he lay unknown. His application to the Kirk-Session for leave to do this is still kept upon the books—a curious interruption amid the minutes of church discipline and economics. One wonders if that homely memorial is kept as it ought to be. It is a memorial not only of the admiration of one poet for another, but of Burns's poignant pity—a wellnigh intolerable pang—for a young soul who preceded himself in the way of poetry and despair, one whose life, destined to better and brighter things, had been flung away like a weed on the dismal strand. Only twenty-three years of poetry and folly had sufficed that other reckless boy to destroy himself and shatter his little lamp of light. Burns was only a few years older, and perhaps, though on the heights of triumph, felt something of that horrible tide already catching his own feet to sweep him too into the abyss. There are few things in the world more pathetic than this tribute of his to the victim who had gone before him.

I may perhaps venture to say, with an apology for recurring to a subject dealt with in another book, that this poetic visit to Edinburgh reminds me of the visit of another poet in every way very different from Burns to another city which cannot be supposed to resemble Edinburgh except in the wonderful charm and attraction for devotees which she possesses. There is indeed no just comparison between Petrarch at Venice and Burns at Edinburgh, nothing but the fantastic link, often too subtle to be traced, which makes the mind glide or leap over innumerable distances and diversities from one thing to another. The Italian poet came conferring glory, great as a prince, and attended by much the same honours and privileges, though he was but a half priest, the son of an exile, in an age and place where birth and family were of infinitely more importance than they are now. He was the perfection and flower of learning and high culture, and a fame which had reached the point which is high-fantastical, and can mount no farther—and he came to a palace allotted to him by the Government, and every distinction which it was in their power to bestow, and demeaned himself en bon prince, adorning with skilful eloquent touches of description the glorious scene beneath his windows, the pageants at which he was an honoured spectator. Nothing could be more unlike the young, shy, proud, yet genial-hearted rustic, holding firmly by that magic wand of poetry which was his sole right to consideration, and facing the curious, puzzled, patronising world with a certain suspicion, a certain defiance, as of one whom no craft or wile could betray or pretension daunt—yet ready to melt into an enthusiasm almost extravagant when a lovely young woman or a noble youth pushed open with a touch the door always ajar, or at least unfastened, of his heart.

"The mother may forget the child

That smiles sae sweetly on her knee;

But I'll remember thee, Glencairn,

And a' that thou hast done for me!"

What Glencairn had done was nothing but kindness, a warm reception which not even the poet's susceptibility could think condescending: but he is repaid with an exuberant, extravagant gratitude. Such was the man; ever afraid to compromise his dignity, but with no measure for the overflowings of his heart. Petrarch, so much more assured in his eminence and superiority to all living poets, was driven from his palace on the Riva and all his delights by the impertinent gibes of some foolish young men. But Burns was flattered and caressed to the top of his bent, and—forgotten, or at least dropped, and no more thought of. He returned to Edinburgh only to find that, the gloss of novelty having worn off, his friends were no longer ready to move heaven and earth in order to bring him to their parties, though probably had he chosen he might have worked himself back "into society" in a slower but more permanent fashion. This, however, he did not choose, but fell back among the convivial middle class, the undistinguished and over merry, where nobody thought it too great humility to refer to Allan Ramsay and Fergusson as his models. It must be recollected, however, that his second visit to Edinburgh, and what seems in the telling a foolish and almost vulgar flirtation, produced one of the most impassioned and exquisite songs of love and despair which has ever been written in any language.

"Ae fond kiss, and then we sever;

Ae farewell, alas! for ever!"

There is a stillness of exhausted feeling in this wonderful utterance which is the very soul of despair.

There has been no more remarkable moment in the experience of the town which has known so many strange and striking scenes, though its interest has little to do with history or even with national feeling. It is pure humanity in an unusual development, an episode in the life of the poet such as has many less important parallels, but scarcely any so fully representative and typical. It discloses to us suddenly, as by a flash of light striking into the darkness, the persons, the entertainments, the sentiments of a hundred years ago. We make improvements daily in external matters, but society—we had almost said humanity—rarely learns. There is not the smallest hope that in Edinburgh or elsewhere a young man of genius in Burns's position would now be either more wisely noticed or more truly benefited by such a period of close contact with people who ought by experience and knowledge to know better than he. The only thing that is probable is a falling-off, not an advance. I think it highly doubtful whether a ploughman from Ayrshire, however superlative his genius, would now be received at all in "the best houses" and by the first men and women in Edinburgh; and if not in Edinburgh, surely nowhere else would such a reception as that given to Burns await the untutored poet. The world has seldom another chance permitted to it, and in this case I cannot but think it would be worse and not better used.

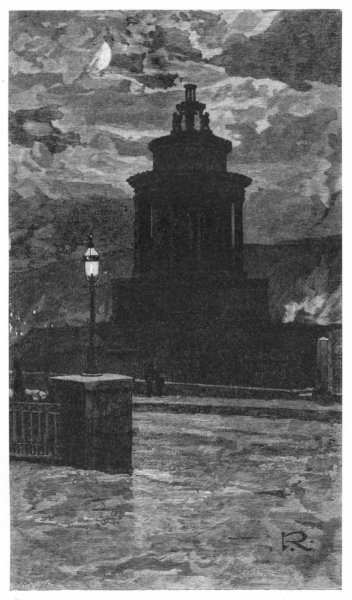

BURNS'S MONUMENT