CHAPTER III

THE SHAKSPEARE OF SCOTLAND

There are many variations in degree of the greatest human gifts, but they are few in kind. The name we have ventured to place at the head of this chapter is one not so great as that of Shakspeare, not so all-embracing—though widely-embracing beyond any other second—not so ideal, not so profound. Walter Scott penetrated with a luminous revelation all that was within his scope, the most different kinds and classes of men, those whom he loved (and he loved all whom it was possible to love) and the few whom he hated, with the same comprehension and power of disclosure. But Shakspeare was not restrained by the limits of any personal scope or knowledge. He knew Lear and Macbeth, and Hamlet and Prospero, though they were beings only of his own creation. He could embody the loftiest passion in true flesh and blood, and show us how a man can be moved by jealousy or ambition in the highest superlative degree and yet be a man with all the claims upon our understanding and pity that are possessed by any brother of our own. Nothing like Lear ever came in our Scott's way: that extraordinary embodiment of human passion and weakness, the forlorn and awful strength of the aged and miserable, did not present itself to his large and genial gaze. It would not have occurred to him perhaps had he lived to the age of Methuselah. He knew not those horrors and dreadful depths of humanity that could make such tragic passion possible. But he had his revenge in one way even upon Shakspeare. Dogberry and Verges, as types of the muddle-headed old watch—pompous, confused, and self-important—are always diverting; but they would have been men not all ridiculous had Scott taken them in hand—real creatures of flesh and blood, not watchmen in the abstract. Our greater poet did not take trouble enough to make them individual, his fancy carrying him otherwhere, and leaving him scarce the time to put his jotting down. To Shakspeare the great ideals whom he almost alone has been able to make into flesh and blood; to Scott all the surrounding world, the men as we meet them about the common thoroughfares of life. He knows no Rosalind nor Imogen, but on the other hand Jeanie Deans and Jenny Headrigg would have been impossible to his great predecessor. Both, we may remark, are incapable of a young hero—the Claudios and the Bertrams being if anything a trifle worse than Henry Morton and Young Lovel. But whereas Shakspeare is greatest above that line of the conventional ideal, it is below that Sir Walter is famous. The one has no restriction, however high he may soar; the other finds nothing so common that he cannot make it immortal.

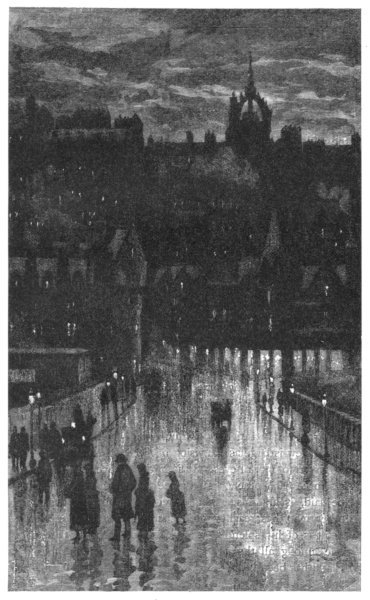

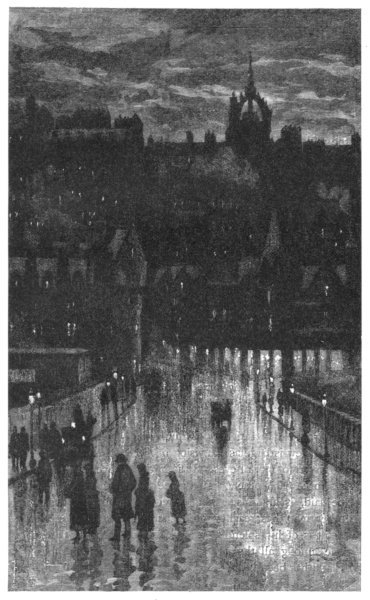

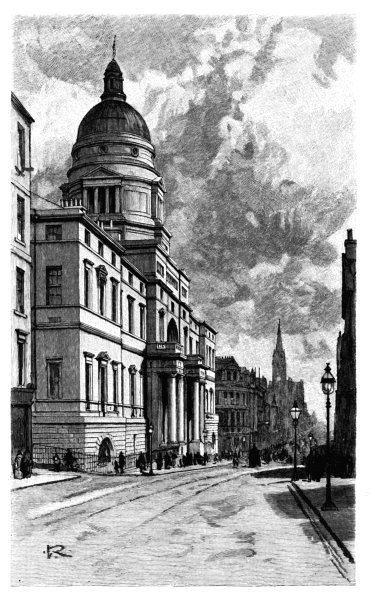

ST. GILES'S FROM PRINCES STREET

It is, however, especially in the breadth and largeness of a humanity which has scarcely any limit to its sympathy and understanding that the great romancist of Scotland resembles the greatest of English poets. They are both so great, so broad, so little restrained by any individual limitations, that a perverse criticism has made this catholic and all-comprehending nature a kind of reproach to both, as though that great and limpid mirror of their minds, in which all nature was reflected, was less noble than the sharp face of a stone which can catch but one ray. They were both subject to political prejudices and prepossessions. Shakspeare has made of many a youth of the nineteenth century an ardent Lancastrian, ready to pluck a red rose with Somerset and die for Margaret and her prince; and Scott in like manner has made many a Jacobite, though in the latter case our novelist is too full of sense even in the midst of his own inclinations to become ever an out-and-out partisan. But, except these prepossessions, they have no parti pris. Every faction renders up its soul of meaning, the most diverse figures unclose themselves side by side. The wit, the scholar, the true soldier, the braggart and thief, the Jew and the Christian, the Hamlet, hero of all time, and Shallow and Slender from the fat pastures of English rural life, come all together, each as true as if on him alone the poet's eye had fixed. And Scott is like him, setting before us with unerring pencil the old superstitious despot of mediæval France, the bustling pedant of St. James's, the ploughmen and shepherds, the churchmen, the Border reivers and Highland caterans, the broad country lying under a natural illumination, without strain or effort, large and temperate as the day. Neither in the greatest poet nor the great romancer is there any force put upon the natural fulness of life to twist its record into a narrow circle with one motive only. It is the round world and all that it inhabits, the grandeur and divinity of a universe, that delights them. Their view is large as the vision of God, or as nearly so as is given to mortal eyes. It is in this, above all, that they resemble each other. In degree Shakspeare, it need not be said, is all-transcendent, reaching heights such as no other man has reached in delineation and creation: but Scott is of his splendid species, one of his kind, the only one among all the many sons of genius with whom this island has been blessed, for whom the boldest could make such a claim.

Walter Scott belongs to all Scotland. He was, no man more, a lover of the woods and fields, of mountain-sides and pastoral braes, of the river and forest, Ettrick and Tweed and Yarrow, and Perthshire—that princely district, half Highland, half Lowland—and the chain of silvery lochs that pierce the mountain shadows through Stirling and Argyle: every league of the fair country he loved. From the Western Isles and the Orkneys to the very fringe of debatable land which parts the northern and the southern half of Great Britain—is his, and has tokens to show of his presence. When he came home to die at the end of almost the most tragic yet most noble chapter of individual history which our century has known, it was the longing of his sick heart above all other that he should not be so unblest as to lay his bones far from the Tweed.

But yet, above all other places, it was to Edinburgh that Scott belonged. His birth, his growth, the familiar scenes of his youth, his education and training, the business and work of his life, were all associated with the ancient capital. George Square—with its homely and comfortable old-fashion, which has nothing to do with antiquity, the first breaking out of the Edinburgh citizens into large space and air outside the strait boundaries of the city, with the Meadows and their trees beyond, and all the sunshine of the south side to warm the deep corps de logis, the substantial and solid mansions which are so grey without yet so full of warmth and comfort within—was the first home he knew, and his residence up to manhood. No boy could be more an Edinburgh boy. Lame though he was, he climbed every dangerous point upon the hills, and knew the recesses of Arthur's Seat and Salisbury Crags by heart before he knew his Latin grammar. His schoolboy fights, his snowballing, the little armies of urchins set in battle array, the friendly feuds of gentle and simple (sometimes attended by hard knocks, as among his own Liddesdale farmers), fill the streets with amusing recollections. And when he was promoted in due time to the Parliament House and to all the frolics of the youthful Bar, and his proud father steps forth in the snuff-coloured suit which Mr. Saunders Fairford wore after him, to tell his friends that "my son Walter passed his private Scots law examination with good approbation," and on Friday "puts on the gown and gives a bit chack of dinner to his friends and acquaintances, as is the custom," how familiar and kindly is the scene, how the sober house lights up, and the good wine about which we have known all our lives comes out of the cellar and the jokes fly round—Parliament House pleasantries and recollections of the witticisms of the Bench gradually giving place to the sallies of the wild young wits, the shaft from the new-bent bow of the young advocate himself. Nothing can be more true and simple than he is through all the tale, or more real than the Edinburgh atmosphere; the fun that is mostly in the foreground; the work that is pushed into corners yet always gets done, though it has not the air of being important except to the excellent father whose steps on the stair are the signal for the disappearance of a chess-board into a drawer or a romance under the papers,—well-known tricks of youth which we have all been guilty of. There is a curious evidence, however, in Lockhart's Life, less known than the usual tales of frolic and apparent idleness, of the professional trick of Scott's handwriting, which showed how steadily he must have laboured even in his delightful, easy, innocently irregular youth. "I allude particularly to a sort of flourish at the bottom of the page, originally, I presume, adopted in engrossing as a safeguard against the intrusion of a forged line between the legitimate text and the attesting signature. He was quite sensible," adds his biographer, "that this ornament might as well be dispensed with; and his family often heard him mutter after involuntarily performing it, 'There goes the old shop again!'" Which of us now could see that flourish without the water coming into our eyes?

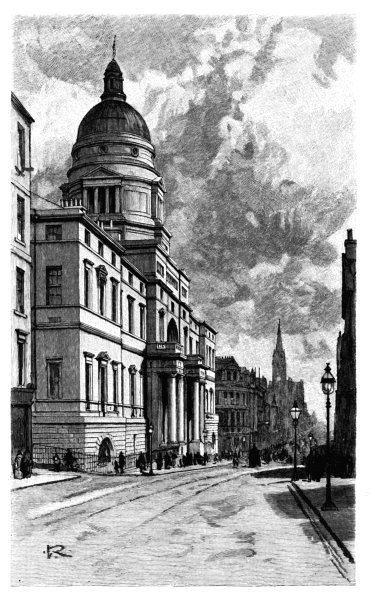

THE UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH

It is impossible to eradicate, from the minds of youthful students at least, the admiration which always attends the performances of the young man who gains his successes without apparently working for them. As a matter of fact, it is the work which we ought to respect rather than that apparently fortuitous accidental result: but nothing will ever cure us of our native delight in an effect which appears to have no vulgar cause, and great has been the misery produced by this prejudice to many a youth who has begun with the tradition of easy triumph and presumed upon it to the loss of all his after-life. But when there shows in the apparent idler a sign like this of many a long hour's labour ignored and lightly thought of, covered over with a pleasant veil of fun and ease and happy leisure, the combination is one that no heart can resist.

Scott had read everything he could lay his hands on while he was still a child, and boasted himself a virtuoso, that is, according to his explanation, at six years old, "one who wishes and will know everything;" but his boyish tastes and triumphs became more and more athletic as he gained a firmer use of his bodily powers. No diseased consciousness of disability in respect to his lameness, like that which embittered Byron, could find a place in the rough wholesome atmosphere of the Edinburgh High School and playgrounds, where nobody was too delicate about reminding him of his infirmity, and the stout-hearted little hero took it like a man, offering "to fight mounted," and being tied upon a board accordingly for his first combat. "You may take him for a poor lameter," said one of the Eldin Clerks, a sailor, with equal friendly frankness to a party of strangers, "but he is the first to begin a row, and the last to end it." To such a youth the imperfection was a virtue the more. When the jovial band strolled forth upon long walks the cheerful "lameter" bargained for three miles an hour, and kept up with the best. They would start at five in the morning, beguiling the way with endless pranks, on one occasion at least without a single sixpence in all their youthful pockets with which to refresh themselves during a thirty miles' round. "We asked every now and then at a cottage door for a drink of water; and one or two of the goodwives, observing our worn-out looks, brought forth milk instead of water, so with that and hips and haws we came in little the worse." Little they cared for fatigue and inconvenience; they were things to laugh over when the lads got back. Scott only wished he had been a player on the flute, like George Primrose in the Vicar of Wakefield, and his father shook his head and doubted the boy was born "for nae better than a gangrel scrapegut"—reproach of little gravity, as the expedition so poorly provisioned was of little harm. Thus the young gentlemen bore cheerfully what would have been hardship to a ploughman, and gibed even at each other's weaknesses without a spark of unkindness, which made the weakness itself into a robust matter of fact not to be brooded over. High susceptibility might have suffered from the treatment, but high susceptibility generally means egotism and inordinate self-esteem, qualities which it is the very best use of public school and college to conjure away.

Nothing indeed more cheerful, more full of endless frolic and enjoyment, fresh air and fun and feeling, ever existed than the young manhood of Walter Scott. Talk of Scotch gravity and seriousness! The houses in which they were received as they roamed about—farmers' or lairds', it was all the same to the merry lads—were only too uproarious in their mirth; with songs and laughter they made the welkin ring. At home in Edinburgh the fun might be less noisy, but it was not less sincere. In the very Parliament House itself the young men clustered in their corner, telling each other the last good things, and with much ado to keep their young laughter within the bounds of decorum. The judge on the Bench, the Lord President himself, greatest potentate of all, was not more safe from the audacious wits than poor Peter Peebles. There was nothing they did not laugh at, themselves and each other as much as Lord Braxfield, and all the humours of a town more full of anecdote and jest, laughable eccentricity and keen satire and amusing comment, than any town in literature. The best joke of all perhaps was Sydney Smith's famous bon mot about the surgical operation, which no doubt he meant as an excellent joke in the midst of that laughing community, where the fun was only too fast and furious. Nowadays, when life is more temperate and the world in general has mended its manners, the habits of that period fill us with dismay; but perhaps after all there was less harm done than appears, and not more of the fearful tribute of young life which our fated race is always paying than is still exacted amid a population much less generally addicted to excess. But that of course increased rather than diminished the jovial aspect of Edinburgh life when Walter Scott was young, and when the few cares he had in hand, the occasional bit of work, interfered very little with the warm and lively social life in the midst of which he had been born. He dwelt, in every sense of the word, among his own people, his friends, the sons of his father's friends, his associates all belonging to families like his own, of good if modest rank and lineage, the "kent folk" of whom Scotland loves to keep up the record. This, which is perhaps one of the greatest advantages with which a young man can enter on life, was his from his infancy. He and his companions had been at school together, together in the college classes, in frequent social meetings, on the floor of the Parliament House. Familiar faces and kind greetings were round him wherever he went. No doubt these circumstances, so genial, so friendly and favourable, helped to perfect the most kind, the most generous and sunshiny of natures. And thus no man could be more completely at once the best product and most complete representative of his native soil.

His life too was as prosperous and full of good fortune and happiness as a man could desire. He married at twenty-six, and a few years later received the appointment of Sheriff-Depute of Selkirkshire, which rendered him independent of the precarious incomings of his profession, and made the pleasure he always took in roaming the country into a necessary part of his life's work. He had begun a playful and pleasurable authorship some time before with some translations from the German, Bürger's Lenore and Goethe's Götz von Berlichingen—the first of which was hastily made into a little book, daintily printed and bound, in order to help his suit with an early love, so easy, so little premeditated, was this beginning. With equal simplicity and absence of intention he slid into the Border Minstrelsy, which he intended not for the beginning of a long literary career, but in the first place for "a job" to Ballantyne the printer, whom he had persuaded to establish himself in Edinburgh—the best of printers and the most attached of faithful and humble friends—and for fun and the pleasure of scouring the country in pursuit of ballads, which was a search he had already entered upon to his great enjoyment. From this nothing was so easy as to float into original poetry, inspired by the same impulse and inspiration as his ballads. One of the ladies of the house of Buccleuch told him the story of the elfin page, and begged him to make a ballad of it; and from this suggestion the Lay of the Last Minstrel arose. The time was ripe for giving forth all that had been unconsciously stirring in his teeming fertile imagination. It came at once like a sudden bursting into flower, with a splendid éclosion, out-bursting, involuntary, unlaborious, delightful to himself as to mankind. From henceforward his name stood in one of the highest places of literature and his fame was assured.

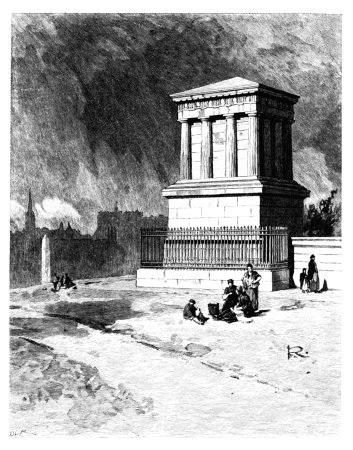

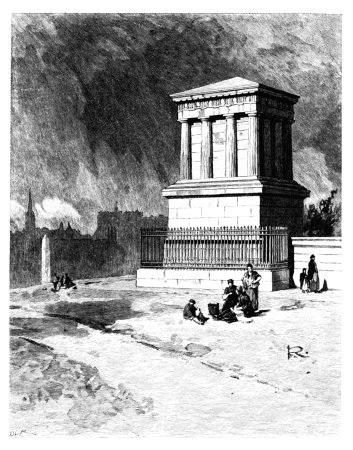

PLAYFAIR'S MONUMENT, CALTON HILL

Nothing could be more unintentional, more spontaneous, almost careless; a thing done for his pleasure far more than with any serious purpose; nothing—except the later beginning, equally unintentional, of a still more important stream of production. The poems of Scott will always be open to much criticism; even those who love them most—and there are many whose love for this fresh, free, spontaneous, delightful fountain of song is strong enough to repress every impulse of criticism and transport it beyond the reach of comment to a romantic enchanted land of its own, where it flows in native sunshine and delight for ever—declining to pronounce any definite judgment as to their greatness. But to Scott in his after-work we are inclined to say no man worthy of expressing an opinion can give any but the highest place. It is true, and the fact has to be admitted with astonishment and regret, that one great writer, his countryman, speaking the same language and in every way capable of pronouncing judgment, has failed to appreciate Sir Walter. We cannot tell why, nor pretend to solve that amazing question. Perhaps it was the universal acclaim, the consent of every voice, that awoke the germ of perversity that was in Thomas Carlyle: an impulse of contradiction, especially in face of an opinion too unanimous, which is one of our national characteristics: perhaps one of those prejudices pertinacious as the rugged peasant nature itself, which sometimes warps the clearest judgment; perhaps, but this we find it difficult to believe, a narrower intensity and passion of meaning in himself which found little reflection in the great limpid mirror which Scott held up to nature. The beginning of Scott's chief and greatest work was as fortuitous, as accidental (if we may use the word), as the poetry. He took up by some passing impulse the idea of a prose story on the events of the 'forty-five, which perhaps he considered too recent to be treated in poetry; wrote (everybody knows the story) half a volume, read it to a trusted critic, who probably considered it foolish for a man who had risen to the heights of fame by one kind of composition to risk himself now with another. It is very likely that Scott himself was easily moved to the same opinion. He tossed the MS. into a drawer, and gave it up. There had been no special motive in the effort, and it cost him nothing to put it aside, to whistle for his dogs, and go out for a long round by wood and hill, or to take his gun or rod, or to entertain his visitors—all of which were more rational, more entertaining, and altogether important things to do than the writing of a dull story, which after all was not his line. For years the beginning chapters of Waverley lay there unknown. They lay very quietly, we may well believe, not bursting the dull enclosure as they might have done had the Baron of Bradwardine been yet born; but that good young Waverley was always a little dull, and might have slept till doomsday had nothing occurred to disturb his rest. One day, however, some fishing tackle was wanted for the use of one of Scott's perpetual visitors at Ashiestiel—not even for himself, for some chance man taking advantage of the Shirra's open house. Visitor arriving in a good hour! fortunate sorner, to be thereafter blessed of all men! Let us hope he got just the lines he wanted and had a good day's sport. For in his search Scott's eyes lighted upon the bundle of written pages. "Hallo!" he must have said to himself, "there they are! Let's see if they're as bad as Willie Erskine thought." In his candid soul he did not think they were very good, unless it was perhaps the description of Waverley Honour, a great mild English mansion which he would admire all the more that it was so unlike Tully Veolan. Perhaps it was the contrast which brought into his teeming brain a sudden vision of that "Scottish manor-house sixty years since," which he went off straightway and built in his eighth chapter with the baron and all his surroundings, which must have been awaiting impatient that happy moment to burst into life.

And thus by spontaneous accident, by delightful, careless chance, so to speak, the thing was done. One wonders by what equally, nay more fortunate unthought-of haphazard it was, that the country rogue Shakspeare, his bright eyes shining with mock penitence for the wildness of his woodland career, and the air and the accent of the fields still on his honeyed lips, first found out that he could string a story together for the theatre and make the old knights and the fair ladies live again. Of this there is no record, but only enough presumption, we think, to make it sufficiently clear that the discovery which has ever since been one of the chief glories of the English name, and added the most wonderful immortal inhabitants to the population, was made, like Scott's, by what seems a divine chance, without apparent preparation or likelihood. In our day much more importance is given to a development which the scientific thinker would fondly hope to be traceable by all the leadings of race and inheritance into an evolution purely natural and to be expected; while, on the other hand, there is nothing which appears more splendid and dignified to others than the aspect of a life devoted to poetry, in which the man becomes but a kind of solemn incubator of his own thoughts. It will always be, however, an additional delight to the greater part of the human race to see how here and there the greatest of all heavenly tools is found unawares by the happy hand that can wield it, no one knowing who has put it there ready for his triumphant grasp when the fated moment comes.

Everybody will remember as a pendant—but one so much more grave that we hesitate to cite it, though the coincidence is curious—the pause made by Dante in the beginning of the Inferno, which resembles so exactly the pause in Scott's career. The great Florentine had written seven cantos of his wonderful poem when the rush of his affairs carried him away from all such tranquil work and left the Latin fragment, among other more vulgar papers, shovelled hastily into some big cassone in the house in Florence from which he was a banished man. It was found there after five years by a nephew who would fain have tried his prentice hand upon the poem, yet finally took the better part of sending it to its author—who immediately resumed Io dico sequitando, in a burst of satisfaction to have recovered what he must have begun with far more zeal and intention than Scott. The resemblance, however, which is so curiously exact, the seven cantos and the seven chapters, the five years' interval, the satisfaction of the work resumed, is, different as are the men and their work, one of those fantastic parallels which are delightful to the fantastic soul. Nothing could be more unlike than that dark and splendid poem to Scott's sunshiny and kindly art; nothing less resembling than the proud embittered exile with his hand against every man, and the genial romancer whose heart overflowed with the milk of human kindness. Yet this strange occurrence in both lives takes an enhanced interest from the curious dissimilarity which makes the repetition of the fact more curious still.

The sudden burst into light and publicity of a gift which had been growing through all the changes of private life, of the wonderful stream of knowledge, recollection, divination, boundless acquaintance with and affection for human nature, which had gladdened the Edinburgh streets, the Musselburgh sands, the Southland moors and river-sides, since ever Walter Scott had begun to roam among them, with his cheerful band of friends, his good stories, his kind and gentle thoughts—was received by the world with a burst of delighted recognition to which we know no parallel. We do not know, alas! what happened when the audience in the Globe Theatre made a similar discovery. Perhaps the greater gift, by its very splendour, would be less easily perceived in the dazzling of a glory hitherto unknown, and obscured it may be by jealousies of actors and their inaptitude to do justice to the wonderful poetry put into their hands. But of that we know nothing. We know, however, that there were no two opinions about Waverley. It took the world by storm, which had had no such new sensation and no such delightful amusement for many a day. It was not only the beginning of a new and wonderful school in romance, a fresh chapter in literature, but the revelation of a region and a race unknown. Scotland had begun to glow in the sunshine of poetry, in glimpses of Burns's westland hills and fields, of Scott's moss-troopers and romantic landscapes, visions of battle and old tradition: but the wider horizon of a life more familiar, of a broad country full of nature, full of character, running over with fun and pawky humour, thrilling with high enthusiasm and devotion, where men were still ready to risk everything in life for a falling cause, and other men not unwilling to pick up the spoils, was a discovery and surprise more delightful than anything that had happened to the generation. The books flew through the island like magic, penetrating to corners unthought of, uniting gentle and simple in an enthusiasm beyond parallel. How the multitude got at them at all it is difficult to understand, for these were the days of really high prices, before the actual cost of a book got modified by one-half as now, and when there were as yet no cheap editions. Waverley was printed in three small volumes at the cost of a guinea. We believe that to buy books was more usual then than now, and there were circulating libraries everywhere, conveying perhaps the stream of literature more evenly over the country than can be attained by one gigantic Mudie. At all events; by whatever means it was procured, Waverley and its successors were read everywhere, not only in great houses but in small, wherever there was intelligence and a taste for books; and the interest, the curiosity, the eagerness, were everywhere overwhelming. I have heard of girls in a dressmaker's workroom who kept the last volume in a drawer, from whence it was read aloud by one to the rest, the drawer being closed hurriedly whenever the mistress came that way. From this humble scene to the highest in the land, where the Prince Regent sat—

"His table spread with tea and toast,

Death-warrants, and the Morning Post,"

these volumes went everywhere. One of them lies before me now in rough boards of paper, with the "blue back" of which one of Scott's correspondents talks, not a prepossessing volume, but independent of externals and all things else except its own native excellence and power.

For fifteen years after, this stream of living literature poured forth in the largest generous volume like a great river, through every region where English was spoken or known. His work was as the march of a battalion, always increasing, new detachments appearing suddenly, now an individual, now a group, to join the line. The Baron of Bradwardine with his attendant bailie; Vich Ian Vohr and noble Evan Dhu, and all the clan; the family at Ellangowan and that at Charlieshope, good Dandie and all his delightful belongings; Jock Jabos and the rest; Monkbarns and Edie Ochiltree, and all the pathos of the Mucklebackits; Bailie Nicol Jarvie and the Dougal Cratur; humours of the clachan and the hillside; Jeanie Deans in her perfect humbleness and truth. It would be vain to attempt to name the new inhabitants of Scotland who appeared out of the unseen wherever Scott moved. Neither to himself nor to his audience could it seem that these friends of all were new created, invented by any man. Scott, who alone could do it, withdrew the veil that had concealed them. He opened up an entire country, a full world of men and women, so living, so various, with their natural garb of fitting language, and their heart of natural sentiment, and the thoughts which they must have been thinking, by inalienable right of their humanity. There might have been better plots or more carefully constructed stories; as indeed in life, heaven knows, all our stories might be much better constructed; but could we conceive it possible that these, our country-folk and friends, could be dismissed again off the face of the earth, how impoverished, how diminished, would Scotland be! The want of them is more than we could contemplate, and we can well understand how our country must have appeared to the world a poor little turbulent country, without warmth or wealth, before these representatives of a robust and manifold race were born.

Yet, amid the delightful enrichment of these productions to the nation and the world, the man himself who produced them was perhaps the finest revelation of all. And here he transcends for once the larger kindred genius of whom we do not know, yet believe, that he was such a man as Scott, though better off in one way and less well in others. Shakspeare must have been somewhat oppressed with noble patrons, which Scott never was—patrons to whom his own splendid courtesy and the magnifying glamour in his poetic eyes must sometimes have made him more flattering than was needful, overwhelming them with magnificent words; but on the other hand he had not those modern drawbacks under which Scott's great career was so bitterly burdened, the strain for money, the constant combat with debt and liability. To bear the first yoke must have taken much of a man's strength and tired him exceedingly: but to bear the second is perhaps the severest test to which any buoyant spirit can be put. And from the very beginning of his career as a novelist Scott had this burden upon his shoulders. He bore the chains very lightly at first with a hundred hairbreadth 'scapes which made the struggle—as even that struggle can be made while the sufferer is strong and young—almost exhilarating, with a glee in the relie