CHAPTER III.

OFF INTO SIDE PATHS.

Wall, the upshot of the matter wuz Al Faizi stayed right there for weeks. He seemed to have plenty of money, and I d’no what arrangement he and Josiah did make about his board, but I know that Josiah acted after that interview with him in the back yard real clever to him, and didn’t say a word more aginst the idee of his not bein’ there.

(Josiah is clost.)

As for me, I would have scorned to have took a cent from him, feelin’ that I got more’n my pay out of his noble but strange conversation.

But Josiah is the head of the family (or he calls himself so).

And mebby he is some of the time.

But suffice it to say, Al Faizi jest stayed and made it his home with us, and peered round, and took journeys, and tried to find out things about our laws and customs.

Thomas Jefferson loved to talk with him the best that ever wuz. And Al Faizi would make excursions to different places round, a-walkin’ mostly, a-seein’ how the people lived, and a-watchin’ their manners and customs, and in writin’ down lots of things in some books he had with him, takin’ notes, I spozed, and learnin’ all he could. One book that he used to carry round with him and make notes in wuz as queer a lookin’ book as I ever see.

With sunthin’ on the cover that looked some like a cross and some like a star.

There wuz some precious stuns on it that flashed. If it wuz held up in some lights it looked like a cross, and then agin the light would fall on’t and make it look like a star. And the gleamin’ stuns would sparkle and flash out sometimes like a sharp sword, and anon soft, like a lambient light.

It wuz a queer-lookin’ book; and he said, when I atted him about it, that he brought it from a country fur away.

And agin he made that gester towards the East, that might mean Loontown, and might mean Ingy and Hindoosten—and sech.

After that first talk with me, in which he seemed to open his heart, and tell what wuz in his mind, as you may say, about our country, he didn’t seem to talk so very much.

He seemed to be one of the kind who do up their talkin’ all to one time, as it were, and git through with it.

Of course he asked questions a sight, for he seemed to want to find out all he could. And he would anon or oftener make a remark, but to talk diffuse and at length, he hardly ever did. But he took down lots of notes in that little book, for I see him.

I enjoyed havin’ him there dretful well, and done well by him in cookin’, etcetery and etcetery.

But the excitement when he first walked into the Jonesville meetin’-house with Josiah and me wuz nearly rampant. I felt queer and kinder sheepish, to be walkin’ out with a man with a long dress, and turban on, and sandals. And I kinder meached along, and wuz glad to git to our pew and set down as quick as I could. But Josiah looked round him with a dignified and almost supercilious mean. He felt hauty, and acted so, to think that we had a heathen with us and that the other members of the meetin’-house didn’t have one.

But if I felt meachin’ over one heathen, or, that is, if I felt embarrassed a-showin’ him off before the bretheren and sistern, what would I felt if Josiah had had his way about comin’ to meetin’ that day?

Little did them bretheren and sistern know what I’d been through that mornin’.

Josiah wore his gay dressin’-gown down to breakfast, which I bore well, although it wuz strange—strange to have two men with dresses on a-settin’ on each side of me to the table—I who had always been ust to plain vests and pantaloons and coats on the more opposite sex.

But I bore up under it well, and didn’t say nothin’ aginst it, and poured out the coffee and passed the buckwheat cakes and briled chicken and etc. with a calm face.

But when church-time come, and Ury brought the mair and democrat up to the door, and I got up on to the back seat, when I turned and see Josiah Allen come out with that rep dressin’-gown on, trimmed with bright red, and them bright tossels a-hangin’ down in front, and a plug hat on, you could have knocked me down with a pin feather.

And sez I sternly, “What duz this mean, Josiah Allen?”

Sez he, “I am a-goin’ to wear this to meetin’, Samantha.”

“To meetin’?” sez I almost mekanically.

“Yes,” sez he; “I am a-doin’ it out of compliments to Fazer; he would feel queer to be the only man there with a dress on, and so I thought I would keep him company; and,” sez he, a-fingerin’ the tossels lovin’ly, “this costoom is very dressy and becomin’ to me, and I’d jest as leave as not let old Bobbett and Deacon Garvin see me appearin’ in it,” sez he.

“Do you go and take that off this minute, Josiah Allen! Why, they’d call you a idiot and as crazy as a loon!”

Sez he, a-puttin’ his right foot forward and standin’ braced up on it, sez he, “I shall wear this dress to meetin’ to-day!”

Sez I, “You won’t wear it, Josiah Allen!”

Sez he, “You know you are always lecturin’ me on bein’ polite. You know you told me a story about a woman who broke a china teacup a purpose because one of her visitors happened to break hern. You praised her up to me; and now I am actin’ out of almost pure politeness, and you want to break it up, but you can’t,” sez he, and he proceeded to git into the democrat.

Ury wuz a-standin’ with his hands on his sides, convulsed with laughter, and even the mair seemed to recognize sunthin’ strange, for she whinnered loudly.

Sez I in frigid axents, “Even the old mair is a whinnerin’, she is so disgusted with your doin’s, Josiah Allen.”

“The old mair is whinnerin’ for the colt!” sez he, and agin he put his foot on the lowest step.

SEZ I, A-RISIN’ UP IN THE DEMOCRAT, “I’LL GIT OUT.”

“Wall,” sez I, a-risin’ up in the democrat, with dignity, “I’ll git out and stay to home. I will not go to church and see my pardner took up for wearin’ female’s clothin’.”

He paused with his foot on the step, and a shade of doubt swept over his liniment.

“Do you spoze they would?” sez he.

“Of course they would!” sez I; “twilight would see you a-moulderin’ in a cell in Loontown.”

“I couldn’t moulder much in half a day!” sez he.

But I see that I wuz about to conquer. He paused a minute in deep thought, and then he turned away; but as he went up the steps slowly, I hearn him say—“Dum it all, I never try to show off in politeness or anything but what sunthin’ breaks it up!”

But anon he come down clothed in his good honorable black kerseymeer suit, and Al Faizi soon follered him in his Oriental garb, and we proceeded to meetin’.

As I say, the excitement wuz nearly rampant as we went in. And I spoze nothin’ hendered the female wimmen and men from bein’ fairly prostrated and overcome by their feelin’s, only this fact, that the winter before a Hindoo in full costoom had lectured before the Jonesville meetin’-house, so that memory kinder broke the blow some. And then some on ’em had been to the World’s Fair, and seen quantities of heathens and sech there.

So no casuality wuz reported, though feather fans wuz waved wildly, and more caraway wuz consoomed, I dare presoom to say, than would have been in a month of Sundays in ordinary times.

But while the wonder and curosity waxed rampant all round, Al Faizi sot silent and motionless as the dead, with his soft, brilliant eyes fixed on the minister’s face, eager to ketch every word that fell from his lips—a-tryin’ to hear the echo of the Great Voice speak to him through the minister’s words, so I honestly believe.

For I think that a honester, sincerer, well-meanin’er creeter never lived and breathed than he wuz; and as days went on I see nothin’ to break up my opinion of him.

Politer he wuz than any female, or minister, I ever see fur or near. Afraid of makin’ trouble to a marked extent, eager and anxious to learn everything he could about everything—all our laws, and customs, and habits, and ways of thinkin’—and tellin’ his views in a simple way of honest frankness, that almost took my breath away—anxious to learn, and anxious to teach what he knew of the truth.

Though, as I said, after that first bust of talk with me he seemed inclined to not talk so much, but learn all he could. It wuz as if he had his say out in that first interview. Dretful interestin’ creeter to have round, he wuz—sech a contrast to the inhabitants of Jonesville, Deacon Garvin and the Dankses, etc.

He didn’t stay to our house all the time, as I said, but would take pilgrimages round and come back, and make it his home there.

Wall, it wuz jest about this time that a contoggler come to our house to contoggle a little for me. I wanted some skirts, and some underwaists, and some of Josiah’s old clothes contoggled.

You know, it stood to reason that we couldn’t have all new things for our voyage, and so I had to have some of our old clothes fixed up. You see, things will git kinder run down once in awhile—holes and rips in dresses, trimmin’ offen mantillys, tabs to new line, and pantaloons to hem over round the bottom, and vests to line new, and backs to put into ’em, and etcetery and etcetery.

And, then, you’ll outgrow some of your things, and have to let ’em out; or else they’ll outgrow you, and you’ll have to take ’em in, or sunthin’.

Sech cases as these don’t call for a dressmaker or a tailoress. No, at sech times a contoggler is needed. And I’ve made a stiddy practice for years of hirin’ a woman to come to the house every little while for a day or two at a time, and have my clothes and Josiah’s all contoggled up good.

This contoggler I had now wuz a old friend of mine, who had made it her home with me for some time in the past, and now bein’ a-keepin’ house happy not fur away, had sech a warm feelin’ for me in her heart, that she always come and contoggled for me when I needed a contoggler.

She had a dretful interestin’ story. Mebby you’d like to hear it?

I hate to have a woman meander off into side paths too much, but if the public are real sot and determined on hearin’ me rehearse her history, why I will do it. For it is ever my desire to please.

It must be now about three years sence I had my first interview with my contoggler. And I see about the first minute that she wuz a likely creeter—I could see it in her face.

She wuz a perfect stranger to me, though she had lived in Jonesville some five months prior and before I see her.

And Maggie, my son’s, Thomas Jefferson’s, wife, hearn of her through her mother’s second cousin’s wife’s sister, Miss Lemuel Ikey. And Miss Ikey said that she seemed to be one of the best wimmen she ever laid eyes on, and that it would be a real charity to give her work, as she wuz a stranger in the place, without much of anything to git along with, and seemed to be a deep mourner about sunthin’. Though what it wuz she didn’t know, for ever sence she had come to Jonesville she had made a stiddy practice of mindin’ her own bizness and workin’ when she got work.

She had come to Jonesville kinder sudden like, and she had hired her board to Miss Lemuel Ikey’s son’s widow, who kep’ a small—a very small boardin’-house, bein’ put to it for things herself though, likely.

I told Maggie to ask her mother to ask her second cousin’s wife to ask her sister, Miss Lemuel Ikey, to ask her son’s wife what the young woman could do.

And the word come back to me straight, or as straight as could be expected, comin’ through five wimmen who lived on different roads.

“That she wuzn’t a dressmaker, or a mantilly maker, or a tailoress. But she stood ready to do what she could, and needed work dretfully, and would be awful thankful for it.”

Then feelin’ deeply sorry for her, and wantin’ to befriend her, I sent word back in the same way—“To know if she could wash, or iron, or do fancy cookin’. Or could she make hard or soft soap? Or feather flowers? Or knit striped mittens? Or pick geese? Or paint on plaks? Or do paperin’?”

And the answer come back, meanderin’ along through the five—“That she wuzn’t strong enough, or didn’t know how to do any one of these, but she stood ready to do all she could do, and needed work the worst kind.”

Then I tackled the matter myself, as I might better have done in the first place, and went over to see her, bein’ willin’ to give her help in the best way any one can give it, by helpin’ folks to help themselves.

I went over quite early in the mornin’, bein’ on my way for a all-day’s visit to Tirzah Ann’s.

But I found the woman up and dressed up slick, or as slick as she could be with sech old clothes on.

And I liked her the minute I laid eyes on her.

Her face, though not over than above handsome, wuz sweet-lookin’, the sweetness a-shinin’ out through her big, sad eyes, like the light in the western skies a-shinin’ out through a rift in heavy clouds.

Very pale complected she wuz, though I couldn’t tell whether the paleness wuz caused by trouble, or whether she wuz made so. And the same with her delicate little figger. I didn’t know whether that frajile appearance wuz nateral, or whether Grief had tackled her with his cold, heavy chisel, and had wasted the little figger until it looked more like a child’s than a woman’s.

And in her pretty brown hair, that kinder waved round her white forward, wuz a good many white threads.

Of course I couldn’t tell but what white hair run through her family—it duz in some. And I had hearn it said that white hair in the young wuz a sign of early piety, and of course I couldn’t set up aginst that idee in my mind.

But them white hairs over her pale young face looked to me as if they wuz made by Sorrow’s frosty hand, that had rested down too heavy on her young head.

She met me with a sweet smile, but a dretful sad one, too, when Miss Ikey introduced me.

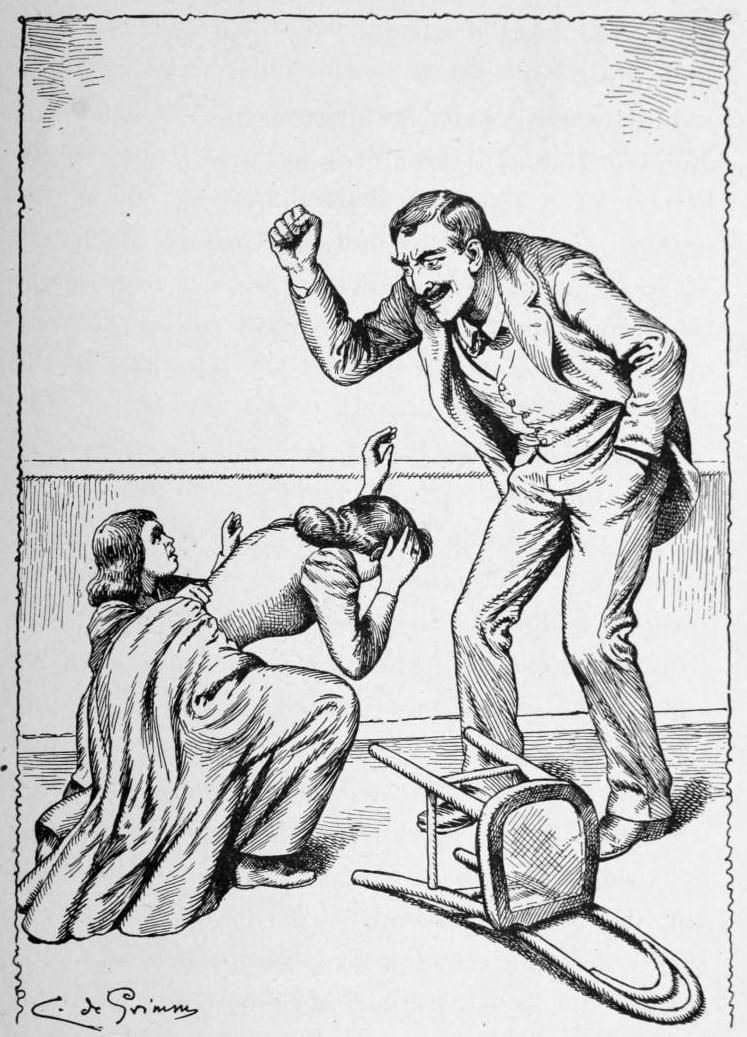

SHE MET ME WITH A SWEET SMILE.

But when I told my errent she brightened up some. But after settin’ down with her for more’n a quarter of a hour, a-questionin’ her in as delicate a way as I could and get at the truth, I found that every single thing that she could do wuz to contoggle.

So I hired her as a contoggler, and took her home with me that night on my way home from Tirzah Ann’s as sech, and kep’ her there three weeks right along.

I see plain that she could do that sort of work by the first look that I cast onto her dress, which wuz black, and old and rusty, but all contoggled up good, mended neat and smooth, and so I see, when she got ready to go with me, wuz her mantilly, and her bunnet; both on ’em wuz old and worn, but both on ’em showed plain signs of contogglin’.

She wuz a pitiful-lookin’ little creeter under her black bunnet, and pitiful-lookin’ when the bunnet wuz hung up in our front bedroom, and she kep’ on bein’ so from day to day, as pale and delicate-lookin’ as a posey that has growed in the shade—the deep shade.

And though she kep’ to work good, and didn’t complain, I see from day to day the mark that Sufferin’ writes on the forwards of them that pass through the valleys and dark places where She dwells. (I don’t know whether Sufferin’ ort to be depictered as a male or a female, but kinder think that it is a She.)

But to resoom. I didn’t say nothin’ to make her think I pitied her, or anything, only kep’ a cheerful face and nourishin’ provisions before her from day to day, and not too much hard work.

I thought I’d love to see her little peekéd face git a little mite of color in it, and her sad blue eyes a brighter, happier look.

But I couldn’t. She would work faithful—contoggle as I have never seen any livin’ woman contoggle, much as I have witnessed contogglin’.

And I don’t mean any disrespect to other contogglers I have had when I say this—no, they did the best they could. But Miss Clark (that wuz the name she gin—Annie Clark), she had a nateral gift in this direction.

She worked as stiddy as a clock, and as patient, and patienter, for that will bust out and strike every now and then. But she sot resigned, and meek, and still over rents and jagged holes in garments, and rainy days and everything.

Calm in thunder storms, and calm in sunshine, and sad, sad as death through ’em all, and most as still.

And I sot demute and see it go on as long as I could, a-feelin’ that yearnin’ sort of pity for her that we can’t help feelin’ for all dumb creeters when they are in pain, deeper than we feel for talkative agony—yes, I always feel a deeper pity and a more pitiful one for sech, and can’t help it.

And so one day, when I wuz a-settin’ at my knittin’ in the settin’-room, and she a-settin’ by me sad and still, a-contogglin’ on a summer coat of my Josiah’s, I watched the patient, white face and the slim, patient, white fingers a-workin’ on patiently, and I stood it as long as I could; and then I spoke out kinder sudden, being took, as it were, by the side of myself, and almost spoke my thoughts out loud, onbeknown to me, and sez I:

“My dear!” (She wuzn’t more’n twenty-two at the outside.)

“My dear! I wish you would tell me what makes you so unhappy; I’d love to help you if I could.”

She dropped her work, looked up in my face sort o’ wonderin’, yet searchin’.

I guess that she see that I wuz sincere, and that I pitied her dretfully. Her lips begun to tremble. She dropped her work down onto the floor, and come and knelt right down by me and put her head in my lap and busted out a-cryin’.

You know the deeper the water is, and the thicker the ice closes over it, the greater the upheaval and overflow when the ice breaks up.

She sobbed and she sobbed; and I smoothed back her hair, and kinder patted her head, and babied her, and let her cry all she wanted to.

My gingham apron wuz new, but it wuz fast color and would wash, and I felt that the tears would do her good.

I myself didn’t cry, though the tears run down my face some. But I thought I wouldn’t give way and cry.

And this, the follerin’, is the story, told short by me, and terse, terser than she told it, fur. For her sobs and tears and her anguished looks all punctuated it, and lengthened it out, and my little groans and sithes, which I groaned and sithed entirely onbeknown to myself.

But anyway it wuz a pitiful story.

She had at a early age fell in love voyalent with a young man, and he visey versey and the same. They wuz dretful in love with each other, as fur as I could make out, and both on ’em likely and well meanin’, and well behaved with one exception.

He drinked some. But she thought, as so many female wimmen do, that he would stop it when they wuz married.

Oh! that high rock that looms up in front of prospective brides, and on which they hit their heads and their hearts, and are so oft destroyed.

They imagine that the marriage ceremony is a-goin’ in some strange way to strike in and make over all the faults and vices of their young pardners and turn ’em into virtues.

Curous, curous, that they should think so, but they do, and I spoze they will keep on a-thinkin’ so. Mebby it is some of the visions that come in the first delerium of love, and they are kinder crazy like for a spell. But tenny rate they most always have this idee, specially if love, like the measles, breaks out in ’em hard, and they have it in the old-fashioned way.

Wall, as I wuz a-sayin’, and to resoom and proceed.

Annie thought he would stop drinkin’ after they wuz married. He said he would. And he did for quite a spell. And they wuz as happy as if they had rented a part of the Garden of Eden, and wuz a-workin’ it on shares.

Then his brother-in-law moved into the place, and opened a cider-mill and a saloon—manafactered and sold cider brandy, furnished all the saloons round him with it, took it off by the load on Saturdays, and kep’ his saloon wide open, so’s all the boys and men in the vicinity could have the hull of Sunday to git crazy drunk in, while he wuz a-passin’ round the contribution-box in the meetin’-house.

For he wuz a strict church-goer, the brother-in-law wuz, and felt that he wuz a sample to foller.

Wall, Ellick Gurley follered him—follered him to his sorrer. The brother-in-law employed him in his soul slaughter-house—for so I can’t help callin’ the bizness of drunkard-makin’. I can’t help it, and I don’t want to help it.

And so, under his influence, Ellick Gurley wuz led down the soft, slippery pathway of cider drunkenness, with the holler images of Safety and old Custom a-standin’ up on the stairway a-lightin’ him down it.

Ellick first neglected his work, while his face turned first a pink, and then a bloated, purplish red.

Then he begun to be cross to his wife and abusive to little Rob, the beautiful little angel that had flown to them out of the sweet shadows of Eden, where they had dwelt the first married years of their life.

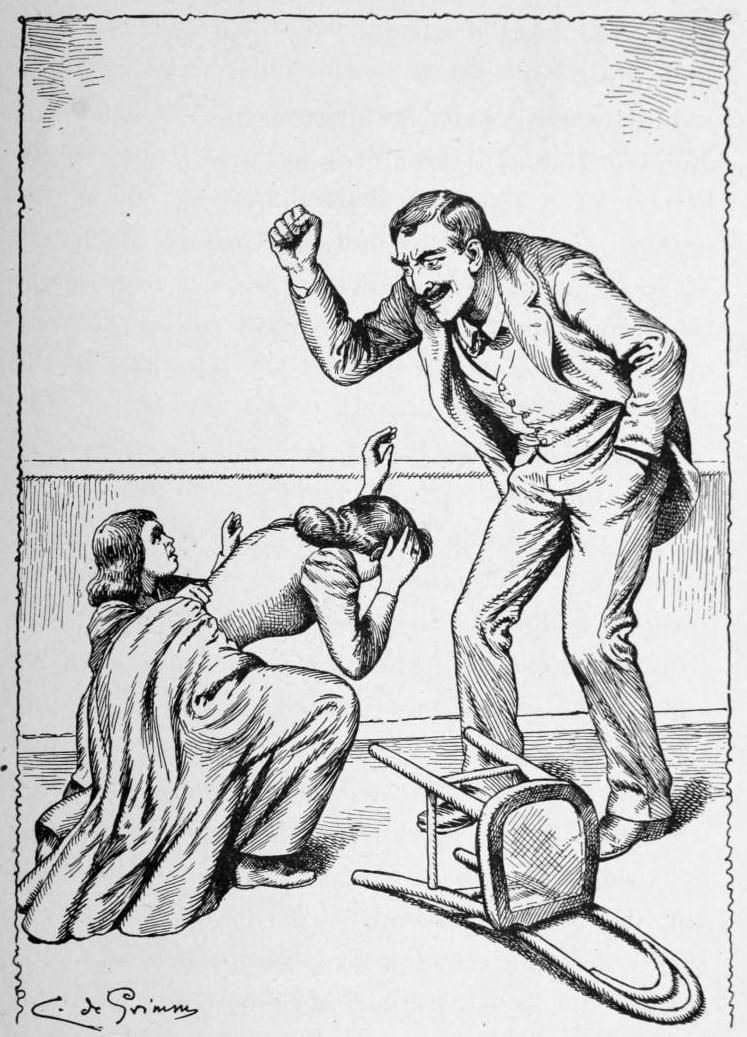

Finally, he got to be quarrelsome. Annie wuz afraid of him. And all of his money and all of hern went to buy that cider brandy (it makes the ugliest, most dangerous kind of a drunk, they say, of any kind of liquor, and I believe it from what I have seen myself, and from what Annie told me of her husband’s treatment of her and little Rob).

FINALLY, HE GOT TO BE QUARRELSOME.

And at last she begun to suffer for food and clothin’ for herself and the child.

And as the drink demon riz up in Ellick’s crazy brain, and grew more clamorous in its demands, and he weaker to contend aginst it, Ellick sold all of the household stuff he could git holt of to appease this dretful power that had got holt of him, body and soul.

Annie took in all the work she could do, did washin’ for the neighbors, who ust to envy her her happiness and prosperity—rubbed and hung out the heavy garments with tremblin’ fingers—sewed with her achin’ head a-bendin’ over the long seams, and her tear-filled eyes dimmed with the pain of unavailin’ agony.

But heartaches and abuse made her weak form weaker and weaker, and then there wuz but little work to do, if she had been as strong as Sampson; so, bein’ fairly drove to it by Agony, and Fear, and Starvation, them three furies a-drivin’ her, as you may say, harnessed up three abreast behind her, a-goadin’ her weak, cowerin’ form with their fire-tipped lashes, she appealed to the brother-in-law.

She told him, what he knew before, that she and little Robbie were starvin’, and she wuz afraid of her life, and she urged him to not sell Ellick any more of the poison that wuz a-destroyin’ him.

He wuz to meetin’ when she went. He wuz dretful particular about his religious observances.

No Hindoos wuz ever stricter about burnin’ their widders on the funeral pyre of the departed than he wuz a-follerin’ up what he called his religion.

(Religion, sweet, pure sperit, how could she stand it, to have him a-burnin’ his incense in front of her? But, then, she has had to stand a good deal in this old world, and has to yet.)

But, as I wuz a-sayin’, there never wuz a Pharisee in old or modern times that went ahead of him in cleanin’ the outside of his platters and religious deep dishes, and makin’ broad the border of his phylakricy. Why, his phylakricy wuz broader and deeper than you have any idee on.

But inside of his platters and deep dishes wuz dead men’s bones!

More’n one quarrel, riz up out of his accursed brandy, had led to bloodshed, besides achin’ and broken hearts without number, and ruined souls and lives.

And his phylakricy ort to be broad, for it had to be used as a pall time and agin, and it covered, so he thought, a multitude of sins.

Yes, indeed!

Wall, as I say, he wuz to a church meetin’. There wuz a-goin’ to be a Association of Religious Bodies for the Amelioration of Human Woe. And he wuz anxious to be sent as a delegate, so he hung on to the last, and wuz appinted.

But finally he got home, and Annie tackled him on the subject nearest her heart, talked to him with tears in her eyes and a voice tremblin’ with the anguished beatin’s of her poor, achin’ heart.

She begged him to not sell her husband any more drink, begged him for her sake and for the sake of little Rob. For she knew that if the man had a tender place in his heart it wuz for his little nephew. He did love him deeply, or as deep as a man like this could love anything above his money and his reputation as a religious leader.

But he wouldn’t promise, and he acted dretful high-headed and hateful to her to cover up his meanness, for he felt that if he should refuse to sell his stuff, it would not only stop his money-makin’, but it would be like ownin’ up that he had been in the wrong.

And he plumed himself, and carried the idee that cider wuz a healthful beverage, and very strengthenin’ in janders and sech. Why, he carried the idee to the world, and mebby in the first place he did to his own soul, so blindin’ is the spectacles of selfishness that he wore, that he wuz a-doin’ a charitable work a-keepin’ that old cider-mill and saloon a-goin’.

So he wouldn’t pay no attention to her pleadin’s, only acted hateful and cross to her, his guilty conscience makin’ him so, I spoze.

And then, too, he wuz in a hurry, for his church duties wuz a-waitin’ for him, and his barrels of cider wanted doctorin’ with alcohol and sech.

So he turned onto his heel and left her.

And Annie went home more broken-hearted than ever, for his cold, cruel sneers and scorn hurt her on the poor heart made sore by her husband’s brutality.

And Ellick went on worse than ever. And it wuz on that very day that his brother-in-law (and to make it shorter we will call him B. I. L.)—it wuz on the very day that the B. I. L. went to New York on his great Amelioratin’ Human Misery errent, that Ellick, crazy drunk with cider shampain, struck little Rob sech a blow that it knocked the child down, and he laid stunted for more’n a hour. And he threatened Annie that he would take her life, because she interfered between him and the boy.

He raved round, like the maniac that he wuz. He said that he would throw her out doors if she didn’t git a good dinner, when there wuzn’t a mite of food in the house to cook. He raved about the house bein’ so freezin’ cold, when there wuzn’t a stick of wood nor a lump of coal.

ELLICK LAY DRUNK IN THE OFFICE.

And finally he reeled off to his usual place of resort. And while the B. I. L. wuz a-raisin’ up in the great meetin’-house, and a-smoothin’ out his phylakricy, and a-layin’ the border of it careful, so’s it would show off well, and then bustin’ out into sech a speech, on the duties of church-members to the sinful and the sorrowin’ round ’em—a speech that riz him up powerful in religious circles—Ellick lay drunk in the office of his cider-mill.

Little Rob lay like a dead child in a cold, bare room, and a white-faced, half-starved mother bent over him with big, despairin’, anxious eyes—bent over him till life come back to his poor, bruised body; and then as darkness crept over the earth she stole away, a-carryin’ him in her arms.

She got a ride with a passin’ teamster, got carried fur off, then got another ride, wuz fed and warmed by pityin’ hearts on the way; so she come to a place nigh Jonesville, onbeknown to anybody.

When Ellick rousted up out of his drunken sleep he went back to a desolate, empty house. His surprise, his grief, sobered him. He flew to the B. I. L., woke him out of a sound sleep filled with visions of his triumphs.

The B. I. L. wuz in a tryin’ place. He wuz about to be riz up to a high position in the meetin’-house. If this story got out, it might and probble would hurt him. Annie must be found and brought back. They jined forces to try to find her. They sot out that very day, but the quest wuz a long one.

Annie stayed a spell with the family who took her in first out of the cold an