CHAPTER II.

A HEATHEN MISSIONARY.

Wall, I wuz a-settin’ in my clean settin’-room on a calm twilight, engaged in completin’ my preperations—in fact, I wuz jest a-puttin’ the finishin’ touches on one of Josiah’s nightcaps and mine.

I put cat stitch round the front of hisen, a sort of a dark red cat.

When all to once I hearn a knock at the west door. I had thought as I wuz a-settin’ a-sewin’ what a beautiful sunset it wuz. The west jest glowed with light that streamed over and lit up the hull sky. All wuz calm in the east, and a big moon wuz jest risin’ from the back of Balcom’s Hill. It wuz shaped a good deal like a boat, and I laid down my sheep’s-head nightcap and set still and watched it, as it seemed moored off behind the evergreens that stood tall and silent and dark, as if to guard Jonesville and the world aginst the gold boat that wuz a-sailin’ in from some onknown harbor. But it come on stiddy, and as if it had to come.

I felt queer.

And jest at that minute I hearn the knock at the west door.

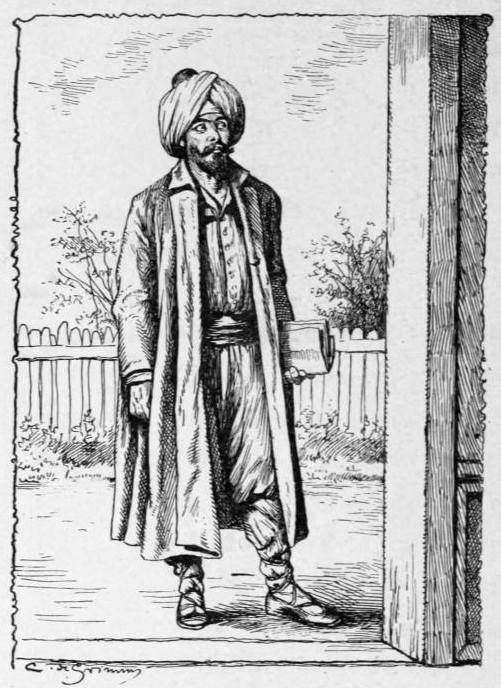

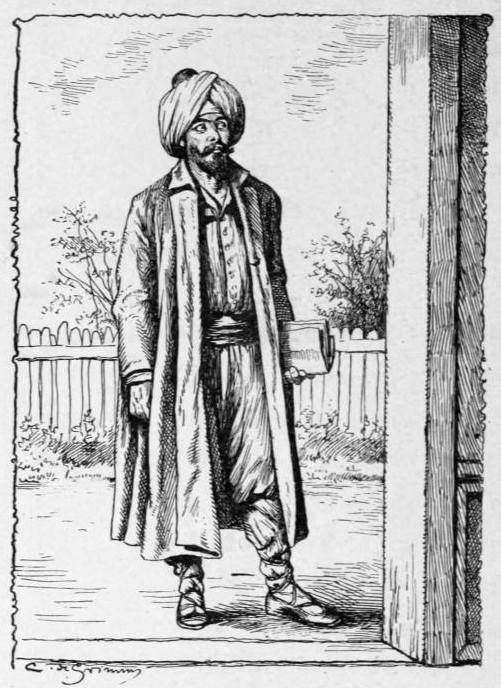

A DARK FIGGER THAT RIZ UP LIKE A STRANGE PICTER AGINST THE SUNSET.

And I went and opened it, and as I did the west wuz flamin’ so with light that it most blinded me at first; but when I got my eyesight agin I see a-standin’ between me and that light a dark figger that riz up like a strange picter aginst the sunset.

His back wuz to the light, and his face wuz in the shadder, but I could see that it wuz dark and eager, with glowin’ eyes that seemed to light up his dark features, some as the stars light up the sky.

And he wuz dressed in a strange garb, sech as I never see before, only to the World’s Fair. Yes, in that singular moment I see the value of travel. It give me sech a turn that if I hadn’t had the advantage of seein’ jest such costooms at that place, I should most probble have swooned away right on my own doorstep.

He wuz dressed in a long, loose gown of some dark material, and had a white turban on his head. Who he wuz or where he come from was a mystery to me.

But I felt it wuz safe anyway to say, “Good-evenin’,” whoever he wuz or wherever he came from; he couldn’t object to that.

So consequently I said it—not a-knowin’ but he would address me back in Hindoo, or Sanskrit, or Greek, or sunthin’ else paganish and queer.

But he didn’t; he spoke jest as well as my Thomas Jefferson could, and when I say that, I say enough, full enough for anybody, only his voice had a little bit of a foreign axent to it, that put me in mind some of the strange odor of Maggie’s sandal-wood fan, sunthin’ that is inherient and stays in it, though it is owned in America, and has Jonesville wind in it—good, strong wind, as good as my turkey feather fan ever had.

Sez he, “Good-evening, madam. Do I address Josiah Allen’s wife?”

Sez I, “You do.”

Sez he, “Pardon this intrusion. I come on particular business.”

Whereupon I asked him to come in, and sot a chair for him.

I didn’t know whether to ask him to lay off his things or not, not a-seein’ anything only the dress he had on, and not knowin’ what the state of his clothes wuz.

And after a minute’s reflection on it, I dassent venter.

So I simply sot him a chair and asked him to set.

He bowed dretful polite, and thanked me, and sot.

Then there wuz a slight pause ensued and follered on. I wuz some embarrassed, not knowin’ what subject to introduce.

Deacon Bobbett had lost his best heifer that day, and most all Jonesville wuz a-lookin’ for it, but I didn’t know whether it would interest him or not.

And Sally Garvin had a young babe. A paper of catnip even then reposed on the kitchen table a-waitin’ until her husband come back to send it, but I didn’t know whether that subject would be proper to branch out on to a man.

So I sot demute for as much as half a minute.

And before I could collect myself together and break out in conversation, he sez in that deep, soft, musical voice of hisen—

“Madam, I have come on a strange errand.”

“Wall,” sez I, in a encouragin’ voice, “I am used to strange errents—yes, indeed, I am! Why,” sez I, “this very day a woman writ to me from Minnesota for money to fence in a door-yard, and,” sez I, “Sime Bentley wuz over bright and early this mornin’ to borrer a settin’ hen. He had plenty of eggs, but no setters.”

Sez I in a encouragin’ axent, for I couldn’t help likin’ the creeter, “I am used to ’em—don’t be afraid.”

I didn’t know but he wuz after my nightgown pattern, and I looked clost at his garb; but I see that it wuz fur fuller than mine and sot different. The long folds hung with a dignity and grace that my best mull nightgown never had, and if it wuz so, I wuz a-goin’ to tell him honorable that his pattern went fur ahead of mine in grandeur.

And then, thinks I, mebby he is a-goin’ to beg for money for a meetin’-house steeple or sunthin’ in Hindoostan, and I wuz jest a-makin’ up my mind to tell him that we hadn’t yet quite paid for the paint that ornamented ourn. And I wuz a-layin’ out to bring in some Bible and say, “Charity begun on our own steeple.”

But jest as I wuz a-thinkin’ this he spoke up in that melodious voice, that somehow put me in mind of palm trees a-risin’ up aginst a blue-black sky, and pagodas, and oasises, and things. Sez he, “Will you allow me to tell you a little of my history?”

I sez, “Yes, indeed! I am jest through with my work.” Sez I frankly, “I have been finishin’ some nightcaps for my pardner, and I sot the last stitch to ’em as you come in. I’d love to set still and hear you tell it.”

So I sot down in the big arm-chair and folded my arms in a almost luxurious foldin’, and listened.

Sez he, “My name is Al Faizi, and I am come from a country far away.” And he waved his hand towards the east.

Instinctively I follered his gester, and his eyes, and I see that the gold boat of the moon had come round the pint, and wuz a-sailin’ up swift into the clear sky. But a big star shone there, it stood there motionless, as he went on.

Sez he, “I have always been a learner, a seeker after truth. When a small boy I lived with my uncle, who was a learned man, and his wife, who was an Englishwoman. From her I learned your language. I loved to study; she had many books. She was the daughter of a missionary, who died and left her alone in that strange land. My uncle was a convert to her faith. She married him and was happy. She had many books that belonged to her father; he was a good man and very learned; he did my people much good while he lived with them.

“I learned from those books many things that our own wise men never taught me, and from them I got a great craving to see this land. I learned from these books and my aunt’s teachings taught me when I was so young that truth permeated my being and filled my heart, that this land was the country favored by God—this land so holy, that it sent missionaries to teach my people. Then I went to a school taught by English teachers, but always I searched for truth—I search for God in mosque and in temple. These books said God is here in this land. So I come. Many of my people come to this great Fair, I come also with them.

“But always I seek the great spirit of God I came here to find. I thought truth and justice would fill your temples, and your homes, and all your great cities.

“I come, I watch for this Great Light—I listened for the Great Voice, I see strange things, but I say nothing, I only think, but I get more and more perplexed. I ask many people to show me the temple where God is, to show me the great mosque where Truth and Right dwell, and the people are blessed by their white shining light, for I thought He would be in all the customs and ways of this wise people, so good that they instruct all the rest of the world. I come to learn, to worship, but I see such strange things, such strange customs. I see cruelties practised, such as my own people would not think of doing. I keep silent, I only think—think much. But more and more I wonder, and grow sad.

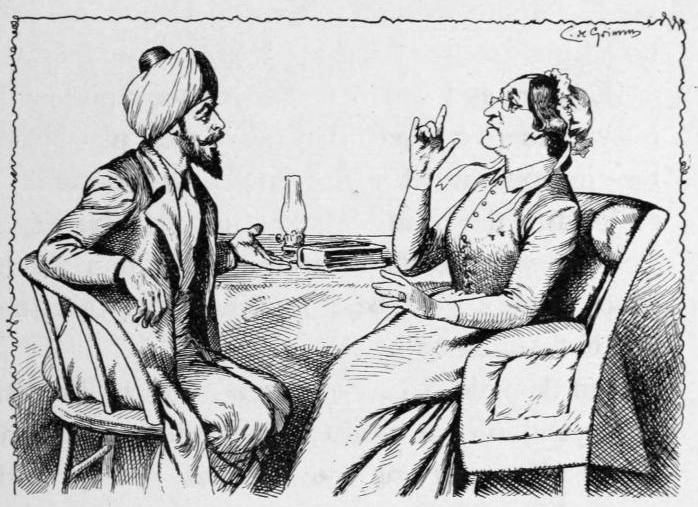

“I DON’T LOVE TO HEAR THAT; THAT SOUNDS BAD.”

“I ask many men, preachers, teachers, to show me the place where God is, the great palace where truth dwells. They take me to many places, but I do not find the great spirit of Love I seek for. I find in your big temples altars built up to strange gods.”

Sez I mildly, “I don’t love to hear that; that sounds bad. I can take you to one meetin’-house,” sez I, “where we don’t have no Dagon nor snub-nosed idols to worship,” sez I.

But even as I spoke my conscience reproved me; for wuz there not settin’ in the highest place in that meetin’-house a rich man who got all his money by sellin’ stuff that made brutes of his neighbors?

What wuz we all a-lookin’ up to, minister and people, but a gold beast! What wuz that man’s idol but Mammon!

And then didn’t I remember how the hull meetin’-house had turned aginst Irene Filkins, who went astray when she wuz nothin’ but a little girl, a motherless little girl, too?

Where wuz the great sperit of Love and Charity that said—“Neither do I condemn thee; go and sin no more”? Wuz God there?

Didn’t I remember that in this very meetin’-house they got up a fair to help raise money for some charity connected with it, and one of the little girls kicked higher than any Bowery girl? Wuz it a-startin’ that child on the broad road that takes hold on death? Wuz we worshippin’ a idol of Expediency—doing evil that good might come?

There wuz poor ones in that very meetin’-house, achin’ hearts sufferin’ for food and clothin’ almost, and rich, comfortable ones who went by on the other side and sot in their places and prayed for the poor, with their cold forms and hungry eyes watchin’ ’em vainly as they prayed, hopin’ for the help they did not get.

Wuz we hyppocrites? Did we bow at the altar of selfishness?

Truly no Eastern idol wuz any more snub-nosed and ugly than this one.

I wuz overcome with horrow when I thought it all over, and sez I—“I guess I won’t take you there right away; we’ll think on’t a spell first.”

For I happened to think, too, that our good, plain old preacher, Elder Minkley, wuzn’t a-goin’ to preach there Sunday, anyway, but a famous sensational preacher, that some of the rich members wanted to call. Yes, many hed turned away from the good gospel sermons of that man of God, Elder Minkley, and wanted a change.

Wuz it a windy, sensational God set up in our pulpit? I felt guilty as a dog, for I too had criticised that good old Elder’s plain speakin’.

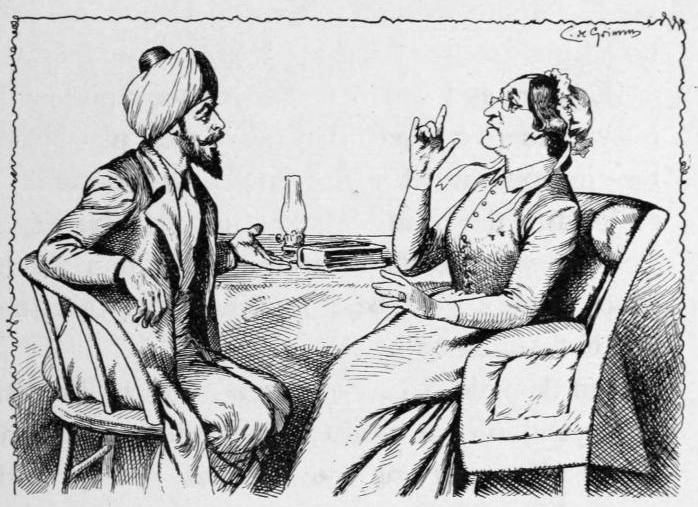

Al Faizi had sot me to thinkin’, and while I wuz a-meditatin’ his calm voice went on—

“I came to a city not far away; there I saw some words you had written. I felt that you, too, desired the truth. I have come to ask you if you have found it—if you have found in this land the place where Love and Justice reign, and to ask you where it is, that I, too, may worship there, and teach the truth to my people.”

I wuz overcome by his simple words, and I bust out onbeknown to me—

“I hain’t found it.” Sez I, and onconsciously I used the words of another—“‘We are all poor creeters,’ but we try to worship the true God—we try to follow the teachin’s of Him who loved us, and give His life to us.”

“The wise man who lived in Galilee and taught the people?” sez he.

“No,” sez I, “not the wise man, but the Divine One—the God who left His throne and dwelt with us awhile in the form of the human. We try to foller His teachings—a good deal of the time we do,” sez I, honestly and sadly.

For more and more this strange creeter’s words sunk into my heart, and made me feel queer—queer as a dog.

“I have read His words. I loved Him when a boy, I love Him still. I go into your great churches sacred to His name. I find in one grand church they say He is there alone, and not in any other. I go into another, just as great, and they say He is there, and not in the one I first visited; and then I go to another, and another, and yet another.

“All have different ways and beliefs. All say God is here within the narrow walls of this church, and not in the others. Oh! I get so confused, I know not what to do. How can I, a poor stranger, trace His footsteps through all these conflicting creeds? I grow sad, and my heart fills with doubt and darkness. Well I remember His words that I had pondered in my heart when a boy—‘That they who loved Him should bear the cross and follow Him,’ and love and care for His poor. In all these great, beautiful churches I hear sweet music. In some I see grand pictures, and note the incense floating up toward the Heavens; in some I see high vaulted roofs, and the light in many glowing colors falls on the bowed forms of the worshippers. I hear holy words, the voice of prayer, but I see no crosses borne, and all are rich and grand. I go down in the low places. I see the poor toiling on unpitied and uncared for. I see these rich people worship in the churches one day, and pray—‘Grant us mercy as we are merciful to others.’

“And then the next day they put burdens on the poor, so hard that they can hardly bear them, the poor, starving, dying, herded together like animals, in wretched places unfit for dumb creatures.

“And ever the rich despise the poor, and the poor curse the rich—both bitter against each other, even unto death.

“I find no God of Love in this.

“I go into your great halls where laws are made—I see the wise men making laws to bind the weak and tempted with iron chains—laws to help bad men lead lives of impurity—laws to make legal crimes that your Holy Book says renders one forever unfit for Heaven. I find no God of Justice in this.”

“No,” sez I, “He hain’t nigh ’em, and never wuz!”

“Well then,” sez he, “why do they not find out the way of truth themselves before they try to teach other people?”

“The land knows!” sez I; “I don’t.”

“Some of your teachers do much good,” sez he; “they are good, and teach some of my people good doctrines. But why ever are they permitted by your government to bring ways and habits into our land that cover it with ruin?

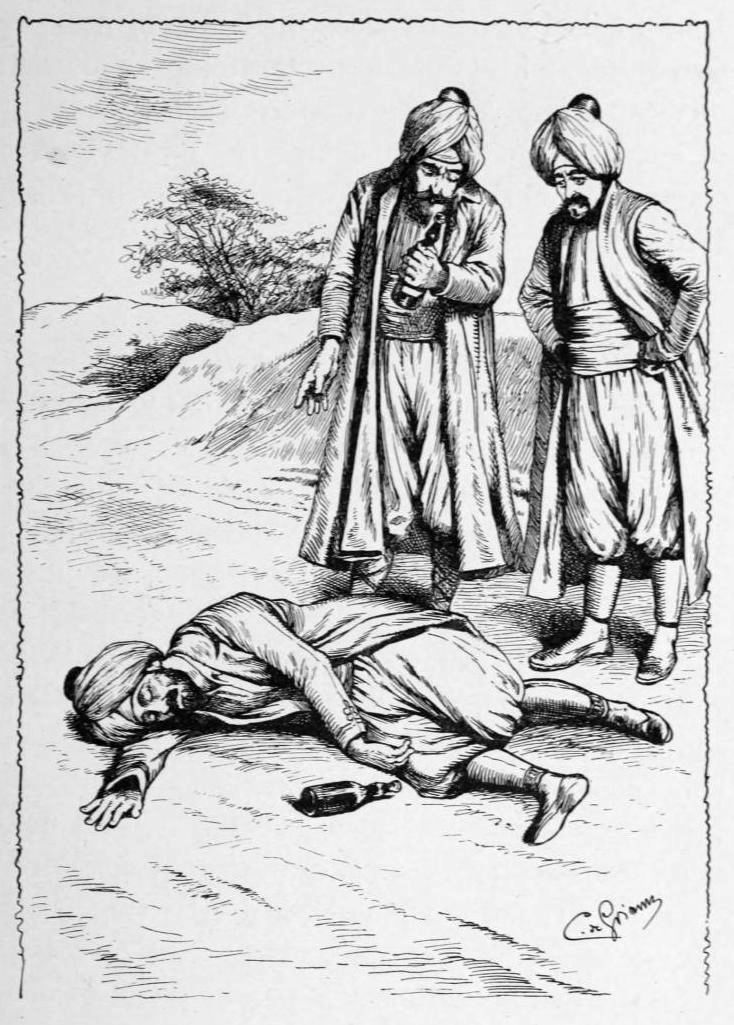

“I was walking once with my own relation, Hadijah, unconverted, and we found one of our people lying drunken by the wayside, with bottles of American whiskey lying by his side. ‘Boston’ was marked on them, a city, I find, that considers itself the centre of goodness and lofty thought. The bottles were empty. Hadijah says to me—‘That man is a Christian.’

“‘THAT MAN IS A CHRISTIAN.’ ‘HOW DO YOU KNOW?’ ‘BECAUSE HE IS DRUNK.’”

“I said—‘No, I think not.’

“‘Yes he is,’ said he.

“‘How do you know it?’ said I.

“‘Because he is drunk.’ Hadijah, not being yet converted, and judging from appearances and from the evidences of his eyesight, associated the ideas and thought that in some way drunkenness was an evidence of Christianity. That belief is largely shared by all heathen people.

“And then I open your Holy Book and find it written, ‘No drunkard shall inherit eternal life,’ and I say to myself, What does it mean that these holy people over the seas, who try so hard to convert us, should send whiskey, and Bibles, and missionaries to us all packed in one great ship?”

Sez I—“The nation don’t mean to do it.” Sez I, “It don’t want to do any sech harm.”

“But I hear of the great power of this nation, could it not prevent it? If it could not prevent it, it must be a weak government indeed. And if truly this great country is so weak and so wicked as to set snares for the heathens—trying to lead them into paths that end in eternal ruin—I think why not keep their missionaries in their own land? They must need them even more than we do.”

Sez I—“Don’t talk so, poor creeter, don’t talk so. Missionaries go out to your land fired with the deathless zeal to save souls—to bring the knowledge of the Christ to all the world.”

“But if they bring the knowledge in the way I speak of, so the heathen honestly believes drunkenness is the sign of Christianity, is it not making a mockery of what they profess to teach?”

I wuz dumbfoundered. I didn’t know how to frame a reply, and so I sot onframed, as you may say.

“I heard the missionaries say, and I read it in your Holy Book, that the liar shall have his portion in the lake that burns forever. The same curses are on them that steal and on them that commit adultery.

“I thought the country that sends these missionaries, rebuking these sins so sharply—I thought their country must be pure and peaceable and holy in its ways. I come here, as I say, seeking the Great Light to guide me. I come here to hear the Great Voice, so I could go back and carry its teachings to our own people. For I thought there must be some mistake, and that the lessons failed in some way to carry the idea of your great government. So I come, I study; and I find that not only was your great government willing to have my poor people enslaved by the drink habit, but it was a partaker in it. It sent over the accursed whiskey and brandy and took a portion of the pay—a portion of the money spent by my poor people for making themselves unfit for earth, and shutting them forever out of Heaven.

“Again, this law that ‘Thou shalt not commit adultery,’ that stands out so plain in the Holy Book, that divorce is only permitted for this one cause, I find this great government, which by its laws breaks even the holy marriage bonds by the committing of this sin—I find that this government makes this sin easy and convenient to commit. It grants licenses to make it lawful and right.

“When I get here and study I see such strange things. Forevermore I wonder, and forevermore I say—Why are not missionaries sent to this people, who do such things?

“And I, even I, so weak as I am and so ignorant, but fired as I am by the love of Christ Jesus—I say to myself, ‘I will tell this people of their sins. I will try to bring them to a knowledge of the pure and holy religion of Christ.’”

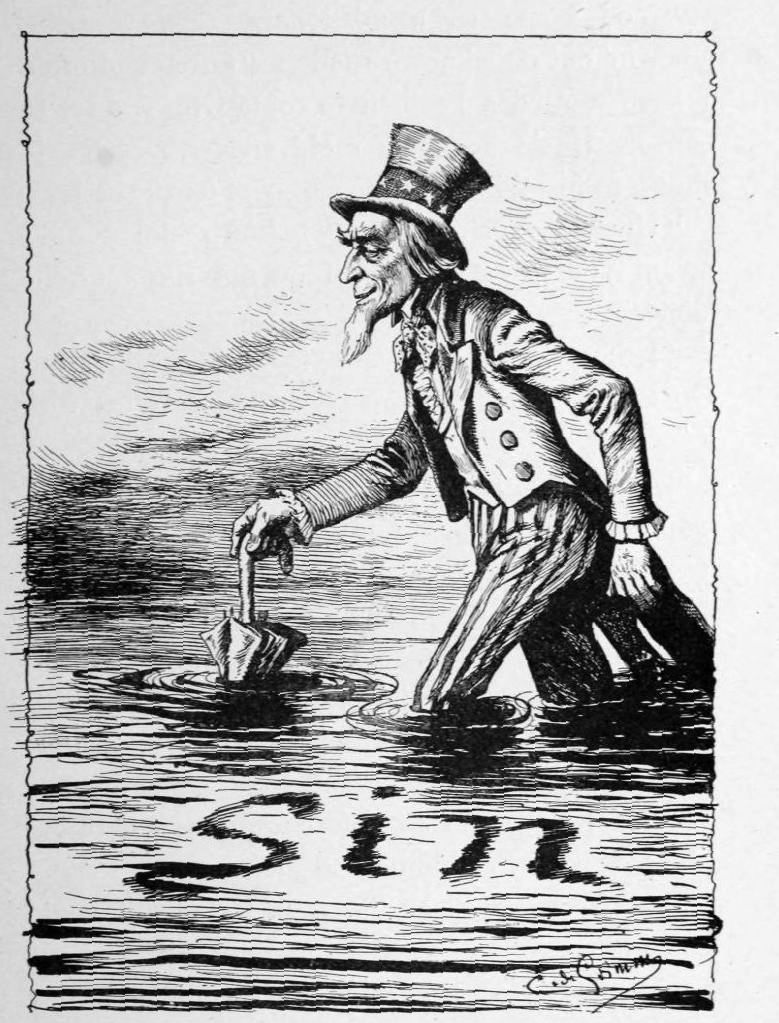

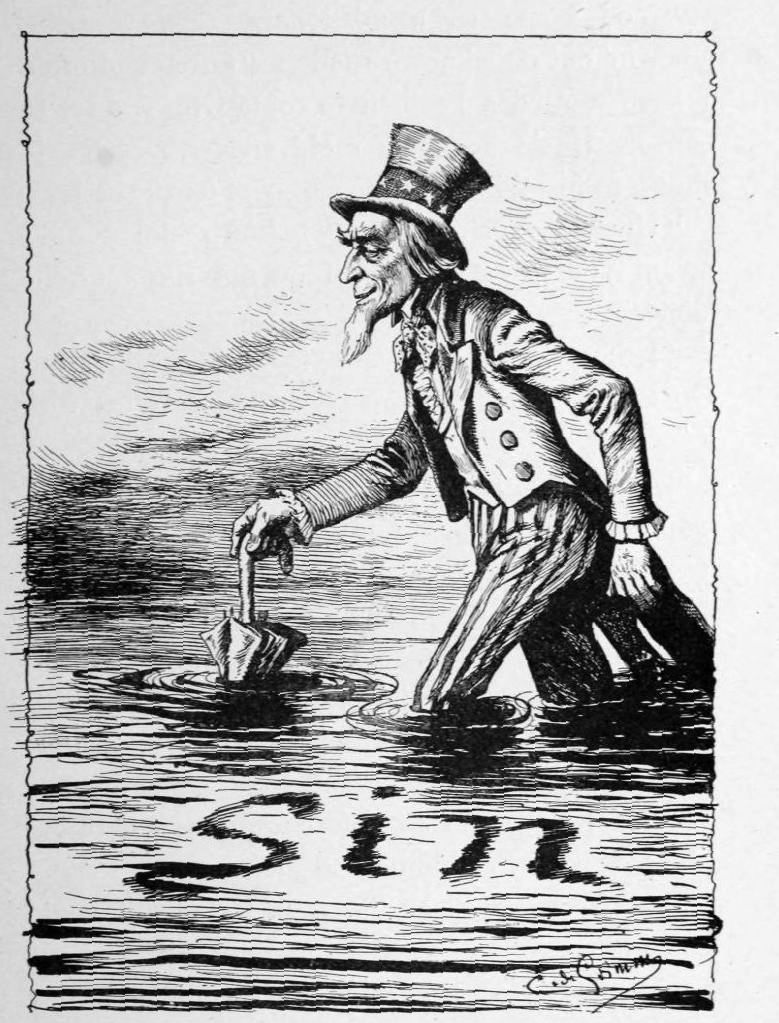

“You come as a missionary, then?” sez I, a-bustin’ out onbeknown to me. “Often and often I have wanted a heathen to come over and try to convert Uncle Sam—poor old creeter, a-wadin’ in sin up to his old knee jints and over ’em,” sez I.

“UNCLE SAM A-WADIN’ IN SIN UP TO HIS OLD KNEE JINTS.”

“Uncle Sam?” sez he; “I know him not. I meant your great people; I do not speak of one alone.”

“I know,” sez I; “that is what we call our Goverment when we are on intimate terms with it.”

“And,” sez I, “you little know what that old man has been through. He wants to do right—he honestly duz; but you know jest how it is—how mistaken counsellors darken wisdom and confound jedgment.”

But the sweet, melodious voice went on—

“Your missionaries preach loud to my people against the sins of stealing and gambling.

“But I find that in this country great places are fitted up for gambling and theft.”

Truly he spoke plain, but then I d’no as I could blame him.

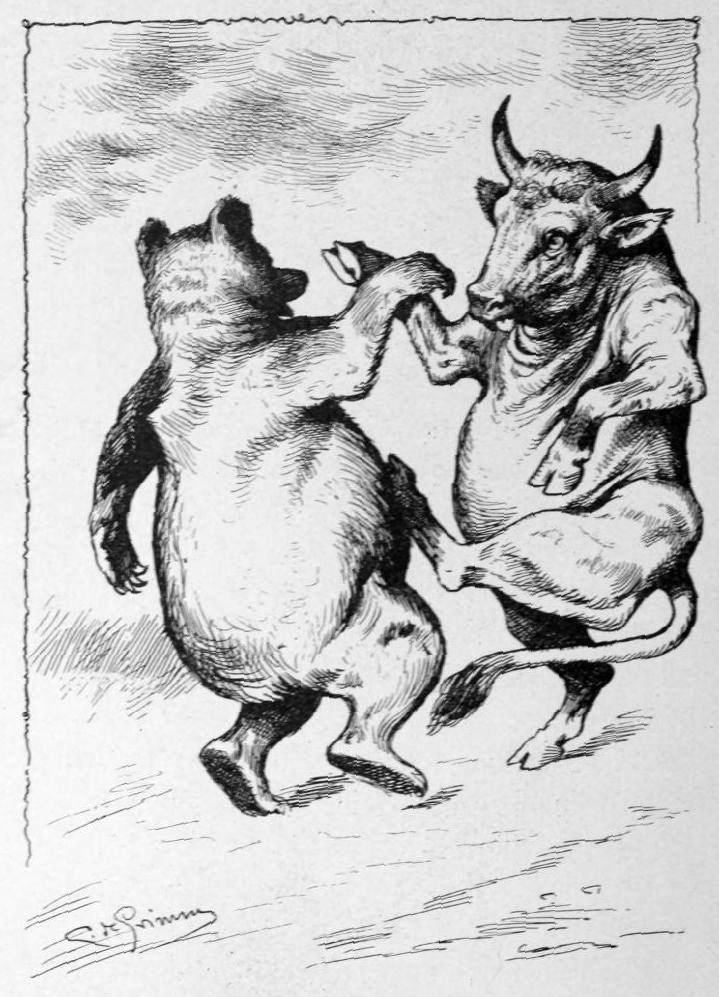

“In these places of theft and gambling, called your stock exchanges, I find that you have people called brokers, and some wild animals called bulls and bears, though for what purpose they are kept I know not, unless it is that they are trained for the Arena. I know not yet all your customs.

“But this I know, that your brokers gamble and steal from the people—sometimes millions in one day. Which money, taken from the common people all over this country, is divided by these brokers amongst a few rich men. Perhaps then the game of bulls and bears, fighting each other for their amusement, begins. I know not yet all your ways.

THE GAME OF BULLS AND BEARS.

“But I know that in one day five million bushels of wheat were bought and sold when there was no wheat in sight—when even during that whole year the crop amounted to only two hundred and eighty millions. There were more than two million, two hundred thousand bushels of wheat bought and paid for that never grew—that were not ever in the world.

“As I saw this, oh! how my heart burned to teach this poor sinful people the morality that our own people enjoy.

“For never were there such sins committed in our country.

“I find your rich men controlling the market—holding back the bread that the poor hungered and starved for, putting burdens on them more grievous than they could bear. These rich men, sitting with their soft, white hands, and forms that never ached with labor, putting such high prices on grain and corn that the poor could not buy to eat—these rich men prayed in the morning (for they often go through the forms of the holy religion)—they prayed, ‘Give us this day our daily bread,’ and then made it their first business to keep people from having that prayer answered to them.

“They prayed, ‘Lead us not into temptation,’ and then deliberately made circumstances that they knew would lead countless poor into temptation—temptation of theft—temptation of selling Purity and Morality for bread to sustain life.”

Sez I, a-groanin’ out loud and a-sithin’ frequent—

“I can’t bear to hear sech talk, it kills me almost; and,” sez I honestly, “there is so much truth in it that it cuts me like a knife.”

Sez he, a-goin’ on, not mindin’ my words—“I felt that I must warn this people of its sins. I must tell them of what was done once in one of our own countries,” sez he, a-wavin’ his hand in a impressive gester towards our east door—

“In one of our countries the authorities learned that stock exchanges were being formed at Osaka, Yokohama, and Koba.

“The police, all wearing disguises, went at once to the exchanges and mingled with the crowd. When all was ready a sign was given, the police took possession of the exchanges and all the books and papers, the doors were locked and the prisoners secured. Over seven hundred were put in prison, the offence being put down—‘Speculation in margins.’

“I yearn to tell this great people of the way of our countries, so that they may follow them.”

“A heathen a-comin’ here as a missionary!” sez I, a-thinkin’ out loud, onbeknown to me. “Wall, it is all right.” Sez I, “It’s jest what the country needs.”

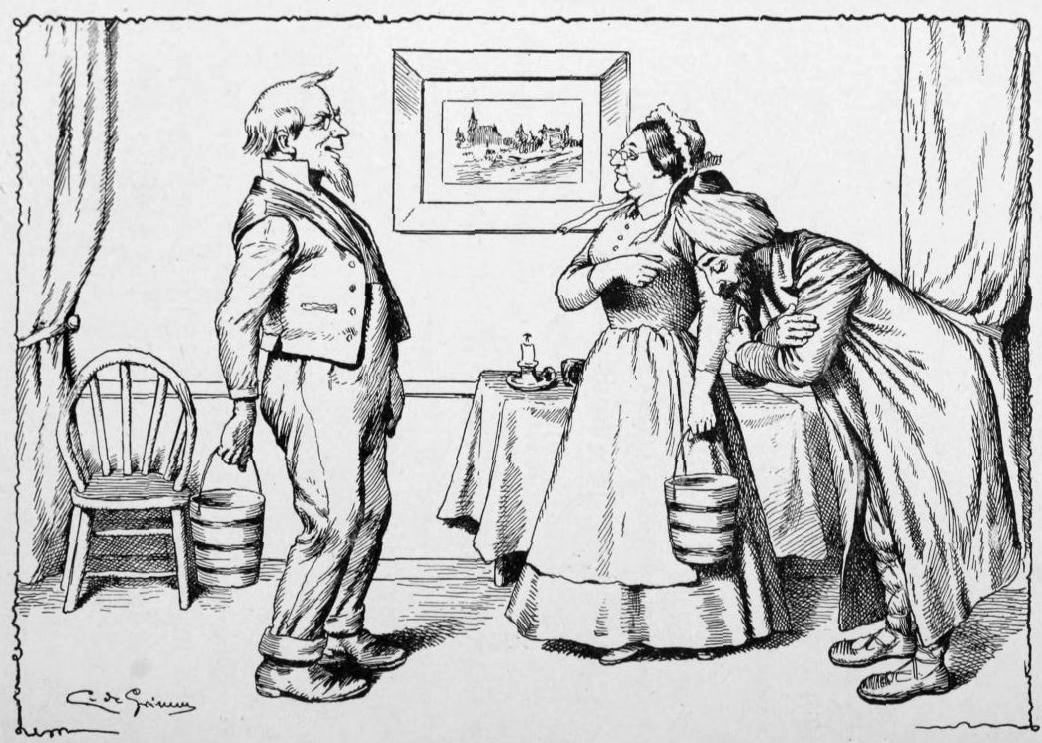

But before I could say anythin’ further, at that very minute my beloved pardner come in.

He paused with a look of utter amazement. He stood motionless and held complete silence and two pails of milk.

But I advanced onwards and relieved him of his embarrassment and one pail of milk, and introduced Al Faizi. Al Faizi riz up to once and made a deep bow, almost to the floor; but my poor Josiah, with a look of bewilderment pitiful to witness, and after standin’ for a brief time and not speakin’ a word, sez he—

AL FAIZI MADE A DEEP BOW, ALMOST TO THE FLOOR.

“I guess, Samantha, I will go out to the sink and wash my hands.”

Truly, it wuz enough to surprise any man, to leave a pardner with no companion but a sheep’s-head nightcap, partly finished, and come back in a few minutes and see her a-keepin’ company with a heathen, clothed in a long robe and turban.

Wall, Josiah asked me out into the kitchen for a explanation, which I gin to him with a few words and a clean towel, and then sez I—“We must ask him to stay all night.”

And he sez, “I d’no what we want of that strange-lookin’ creeter a-hangin’ round here.”

And I sez, “I believe he is sent by Heaven to instruct us heathens.”

And Josiah said that if he wuz sent from Heaven he would most probble have wings.

He didn’t want him to stay, I could see that, and he spoke as if he wuz on intimate terms with angels, a perfect conoozer in ’em.

But I sez, “Not all of Heaven’s angels have wings, Josiah Allen, not yet; but,” sez I, “they are probble a-growin’ the snowy feathers on ’em onbeknown to ’em.”