CHAPTER XVI.

EDENSOR AND THE DUKE OF DEVONSHIRE.

So anon we found ourselves in the smoky, grimy, dirty city. A heavy black cloud seemed to hang overhead, seemin’ to shade the hull spot; but then I didn’t want to lay it up agin ’em, for I knew we had our own cities, that had to set down under a cloud of smoke jest as they did—Pittsburg, and others, etcetery.

I can’t say that I took sech a sight of comfort here in Sheffield, but Josiah and Martin seemed to enjoy themselves a-goin’ round and seein’ all they could.

Martin said it wuz a sight to see how perfectly each workman did his work, and how faithful they wuz to their employers; he said he wished he had sech men to work for him.

And it wuz curous to think on. As nigh as I could make out, generations of one family would work on and on, a-workin’ at one part of a jack-knife, for instance, a-keepin’ right on—a grandpa, and his son, and his son’s son, and etcetery—all contented and industrious and awful handy, as they would naterally be, a-workin’ on at one thing year after year, year after year; mebby a-makin’ a rivet to put into a handle of a knife.

It stands to reason that they would learn to do it well after workin’ at the same thing over and over for hundreds of years. And these workmen seemed to be sot on doin’ jest the best work that they could, and stay right on in the same place.

“And,” sez Josiah, “I wonder if Ury’s boy and grandson and great-grandson will be willin’ to keep right on workin’ for me?”

Sez I, “Do you expect to outlive Ury’s grandson, Josiah Allen?”

Sez he, “They did in Bible times.” Sez he, “I wouldn’t be nigh so old then as Methusler,” and he went on—“I use my help as good agin as they do here. If I should put Ury to work in sech a dark, dirty, onhandy place as these workmen have, he’d kick in a minute and leave me; but here they work, generations of ’em, all in one place.”

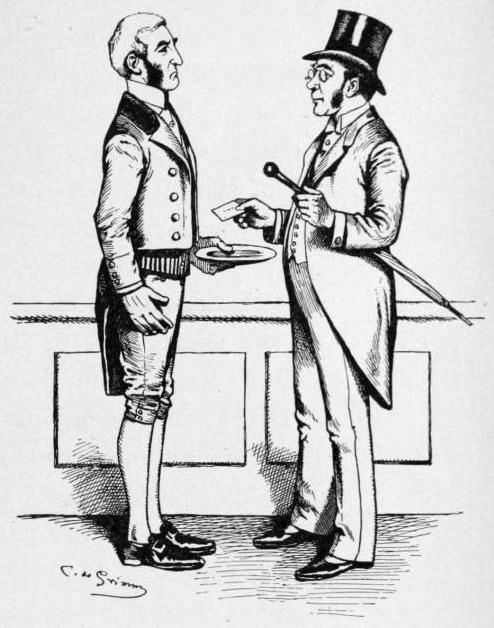

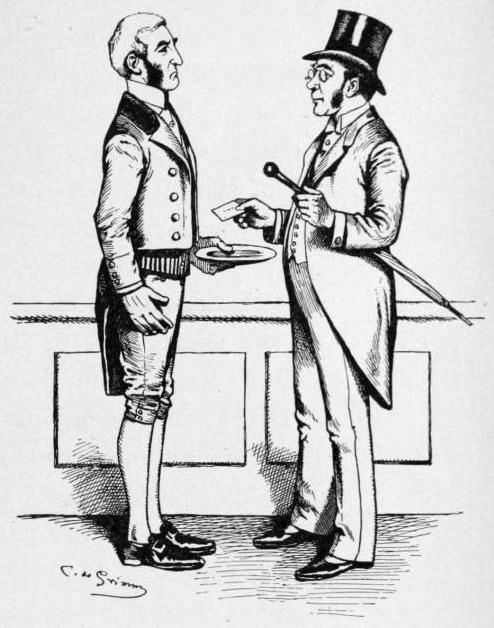

“IT DON’T PAY TO TUSSEL WITH ’EM.”

Sez I feelin’ly, “I wish I could git sech a generation of hired girls; but no sooner duz an American housekeeper git a hired girl broke in, so she can bile a potato decent, or make a batch of bread, than off she trapes somewhere else to better herself. It don’t pay to tussel with ’em,” sez I.

“Wall,” sez Josiah, “you ort to go into some of these factories; it is a sight to see how perfect everything is done. One part of a knife, for instance, done in one house, and then another house doin’ another part, and then another another, and every part done jest as well as it can possibly be.”

And then Josiah went on about that wonderful knife they make here, with a new blade added for every year.

And bein’ we wuz alone, and I hadn’t nothin’ else on my mind, I moralized some, and sez I—

“Old Fate is makin’ her knife pretty stiddy, and seems to add a new blade every year for us to cut our feelin’s on, and jab ourselves with.”

And sez I, “They don’t hurt any the less because we dig the metal ourselves and shape the sharp blades with our ignorant hands, not knowin’ what we’re a-workin’ on, and some on ’em,” sez I, “handed down from foolish, ignorant workmen who have gone before—queer!” sez I, “passin’ queer!”

“Yes,” sez Josiah, “it wuz quite a sight; Martin and I enjoyed it.

“But the drinkin’ here in Sheffield,” sez Josiah, “is sunthin’ dretful to witness.” Sez he, “I thought we had drinkin’ habits in America, but I never see nothin’, nor I don’t believe anybody else did, to compare with some of the places we visited to-day. Why,” sez he, “it would do a W. C. T. U. good to jest look at ’em.”

“Good?” sez I sternly.

“Wall, yes,” sez he; “it would set ’em to kinder soarin’ and wavin’ them banners of theirn and talkin’—you know jest how they love to talk,” sez he.

Sez I, “You better stop right where you are.” Sez I, “Do you realize that you are talkin’ about your pardner?”

“Wall, yes,” sez he; “that’s what I wuz kinder figgerin’ on—Heaven knows you love to talk, you can’t dispute that.”

I wouldn’t dane to argy with him.

But, indeed, it wuz a sight to walk through some of the low, dingy, filthy streets, with saloons on every side flauntin’ their brazen signs, and men and wimmen with bloated, sodden faces, that strong drink had almost changed into the faces of animals.

The same sin—the same useless, needless sin, parent of all other vices—jest as bad on this side of the Atlantic as in Jonesville and America, and worse.

I left it there a-performin’ and cuttin’ up, and I found it here actin’ jest the same. You’d think after crossin’ the Atlantic it would git sobered up a little—seein’ so much water and everything.

But it hadn’t. It wuz jest the same reelin’, disgraceful, foolish, leerin’, bloated Shame—

Jest as bad in Sheffield as it wuz in Jonesville and Chicago, and worse.

It wuz enough to melt a stun with pity, and make hard eyes weep with sorrer and flash with a righteous indignation, at the Nations that don’t devise some means of wipin’ out this gigantic cause of wickedness, woe, and want.

They can connect worlds together with chains of lightnin’, they can make roads through the earth and on top of it, and in all ways; then why can’t they keep a man from drinkin’ a tumbler full of whiskey? They could if they wanted to, and all put in together.

Wall, wuzn’t it a change to leave this smoky, grimy city and find ourselves in the open, beautiful English country, and in the most beautiful part of it, too?

We went by railroad to Matlock Bath, and from there went in a carriage to the little village of Edensor, the loveliest little village I ever sot eyes on. Its housen are all built in some quaint, beautiful style of architecture, and it looks like a picter, and a great deal handsomer than lots of picters I’ve seen—chromos and sech.

This village belongs to the Duke of Devonshire, and is on his estate, which is the finest in England, and I guess on this hull earth.

And I d’no whether they’ve got any on any other planet that goes ahead on’t. Mebby Jupiter has, but I don’t really believe it.

Why, jest its pleasure park—the door-yard, as you may say—has two thousand acres in it.

This estate, known as Chatsworth, is twelve milds from Edensor, and nobody could describe the beauty of the landscape all about us as we passed onwards.

As we went acrost a corner of this immense door-yard, through the most beautiful pieces of woodland, and the verdant slopes covered with velvety sward, great, beautiful pheasants and herds of deer would look round at us and then walk off, not a mite afraid, fearless as they will be if they’re used well. Anon we would ketch a glimpse of some enchantin’ vista, with herds of contented cattle, makin’ picters of themselves aginst the background of green grass and noble trees centuries old.

From a little hill top we could see twelve milds in every direction, and not a foot of land that this man didn’t own.

Twelve milds! the idee! It seems more’n he ort to have on his mind.

Anon we reached a beautiful stun bridge, designed by Michael Angelo, and crossin’ the little river, went up to the great iron and gilt entrance gates.

MARTIN SENT HIS CARD IN.

Martin sent his card in to somebody that takes care of the premises, I guess (and how he dast to ask any favors of this gorgeous-dressed creeter in knee-breeches, I d’no, but he did, bold as brass), and word come back that we could look over the place, and one of the hired men wuz sent to go with us and show us round. It wuz well he come; we should have got lost, sure as the world. But lost in sech a place—sech a place! Why, I’d read the Arabian Nights quite a good deal, and a considerable number of fairy stories about enchanted castles, and sech. But never did I ever hear, in a book, or out on’t, of sech magnificence as I see here.

First we went through a great courtyard into the splendid entrance hall, seventy feet long if it wuz a inch; the wall and ceilin’s ornamented with frescoes, all representin’ the life and death of Cæsar. We went up a majestic staircase, with all the richly ornamented columns and statutes it needed for its comfort, and more, too, it seemed, though they wuz beautiful beyend tellin’; and here we went into the State Apartments of the house.

I spoze they are called State Apartments because in every room there’s enough of beauty and grandeur to supply a hull State, if it wuz scattered even, and I don’t mean Rhode Island either, but New York and Maine and sech sizable ones.

Why, every one of these lofty ceilin’s is painted with picters handsome enough for the very handsomest handkerchief pin, if they wuz the right size. The hired man told us what some of the picters represented—Aurora (and, oh, how beautiful Aurora wuz!), and one wuz the “Judgment of Paris.”

I hadn’t no idee before that Paris jedgment wuz so perfectly beautiful; I spozed it wuz kinder triflin’. They seemed, as fur as I could make out, to be a-samplin’ apples—lovely creeters they wuz that wuz standin’ round.

And then there wuz “Phaeton in the Chariot of the Sun.”

It didn’t look a mite like our phaeton—fur more magnificent.

Room after room opened into each other, all different as stars differ from each other, but every one full of glory; all full of the treasures of every land—Persia, Egypt, and every other.

The hired man drawed our attention to the presents of kings and princes, and all the rare objects of art and virtue.

But I sez, “As fur as virtues is concerned, I d’no as kings would be any more apt to git hold of ’em than common men, or so apt, but,” sez I, “call ’em perfectly beautiful, and I agree with you.”

In them magnificent and immense rooms are picters by Landseer, Holbein, Salvator Rosa, Raphael, Rubens, Claude Lorraine, Correggio, Hogarth, Titian, Michael Angelo, etc. A great many with the autographs of the painters—priceless, absolutely beyend price, are these works of art.

And if I should talk a week, I couldn’t describe all the beautiful objects we see there, so valuable that one on ’em would make a man rich.

In one room wuz a clock of gold and malachite—a present from the Emperor Nicholas, worth a thousand guineas, and a broad, shinin’ table of one clear sheet of transclucent spar, and a great table of clear malachite. I’d be glad to git enough of it for an earring for Tirzah Ann.

In one room we see a picter by Holbein of Henry VIII., and a rosary belongin’ to him. I wondered as I looked on’t what that poor, misguided creeter ust to pray about as he handled them beads. He couldn’t want any more wives than he had, it seemed to me. Mebby he wuz a-wishin’ some of the time that he wuz back with Katharine, that noble creeter who said—

“Weep, thou, for me in France, I for thee here;

Go count thy way with sighs, I mine with groans.”

And when they had that lawsuit of theirn (he gittin’ after another woman, and wantin’ to git rid of her), after he’d bought off the jedge, Katharine sez to Henry—liftin’ her right arm up towards Heaven—

“There sits a Jedge no king can corrupt.”

Noble, misused creeter! I’ll bet if them beads could have told what wuz said over ’em, they would have said that Henry thought of her, his lawful wife, when his memory wuz sick of recallin’ Anne Boleyn, Anne of Cleves, etc., etc., etc., etc., etc. But to resoom.

We see the bed that George II. died in. The chairs and footstools used by George III. and his queen. And the two chairs used by William IV. and Queen Adelaide at their coronation. And then we see the most beautiful tapestry that ever wuz made, and busts and statutes. Richly colored, priceless old china filled the splendid cabinets inlaid with finest mosaic work—in fact, the hull length of these rooms, openin’ into each other so that you could see their hull length of 550 feet, wuz full of the most costly and beautiful objects man ever made.

The oak floor wuz polished, and shone like a mirror.

The library wuz one hundred feet long of itself, with columns risin’ from floor to ceilin’ and a gallery runnin’ round it, and two more openin’ out of it, with alcoves of Spanish mahogany, these full of picters by Landseer and others, and medallions, etc., etc., etc., and full of the choicest literature of every land.

And then there wuz a private chapel that went ahead of any meetin’-house I ever see or ever expect to, all marble and spar and wonderful wood-carvin’s, and picters from the old masters filled it full of beauty and glory. Faith and Hope wuz there all carved out beautiful, so’s you could see ’em right before you, as well as feel ’em in your heart.

In the sculpter gallery is the most wonderful treasures, busts and statutes and mosaics, relicks from every land and age, and beautiful figgers, almost alive, by Canova, Powers, Thorwaldsen, Gibson, Bartolini, etc., etc. Some wuz presented by emperors and kings, and some on ’em bought by the Duke and his folks. The hull room, one hundred feet long, is full of the rarest treasures that can be collected; it made my brain fairly reel beneath my best bunnet to see the wealth of glory and beauty, and Al Faizi turned away from it a spell and looked thoughtfully out of the winder.

But I see that here, too, wuz a picter that no artist could reproduce, and so it wuz in every winder that you could look out of. A green, velvety lawn a hundred feet wide and over five hundred long, bordered by most beautiful colored flowers, and out of another winder you could see the velvety slopes, with walks and river and bridge, and way off the noble trees and terraces, one risin’ above another, all full of beautiful plants and shrubs. And in the centre from the top down, hundreds of feet, wuz a great flight of stun steps, thirty feet wide, down which flows and sparkles a sheet of water, reflectin’ in its mirror-like surface all the white statutes on its margin, till it reaches the edge of the broad gravel walk, when it disapears right down into the earth and flows off in some curous, underground way to the river.

Josiah wuz all rousted up when he see this, and, as is the way of my dear, ardent-souled companion, he tore a page out of his account-book, and begun to make calculations on’t.

And I sez with a sithe—“What are you a-figgerin’ on now, Josiah Allen?”

“Oh! I’m plottin’ out a lovely addition to the beauty of our home, Samantha—I’m a-plannin’ sunthin’ so uneek and fascinatin’ that it will make the Jonesvillians open their eyes in astonishment and or.”

“What is it?” sez I.

“I’m a-plannin’ on how we can have a waterfall on our back doorsteps.” Sez he, “I hain’t seen anything so perfectly beautiful and strikin’ as this sence I come to the Old Country, and we can have one jest as well as not. You know our back steps are quite high, and how beautiful they would look with the sparklin’ water flowin’ down ’em—how refreshin’ it would be in hot weather to have a waterfall right on your own doorsteps, and set in the open back door, right on its banks, as it were, and hear the murmur of the water, and see it a-glidin’ down towards the smoke-house. We might have it dissapear,” sez he, “between the smoke-house and the ash-barrel.”

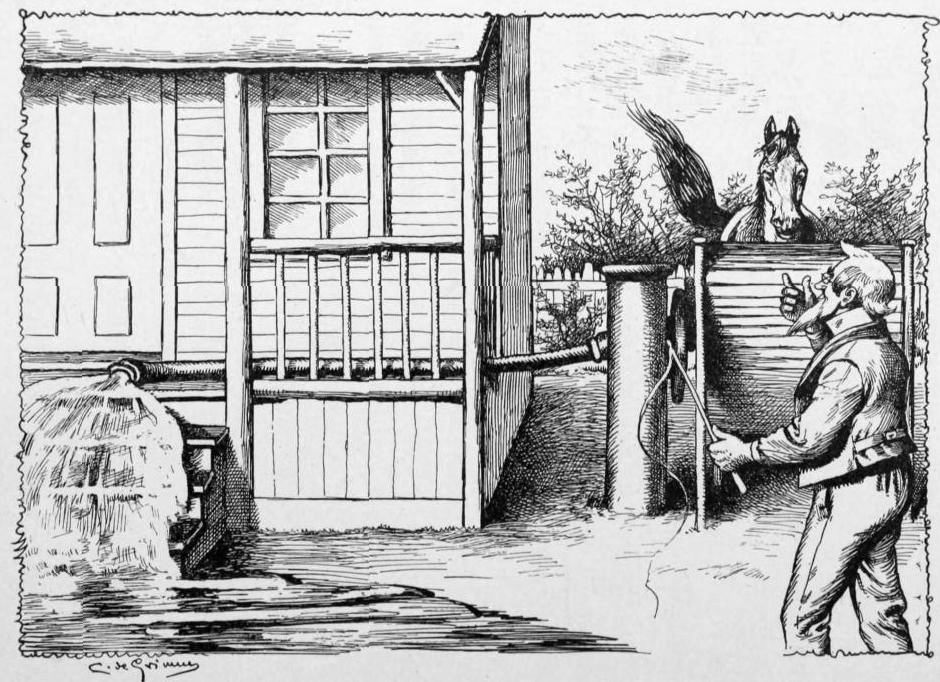

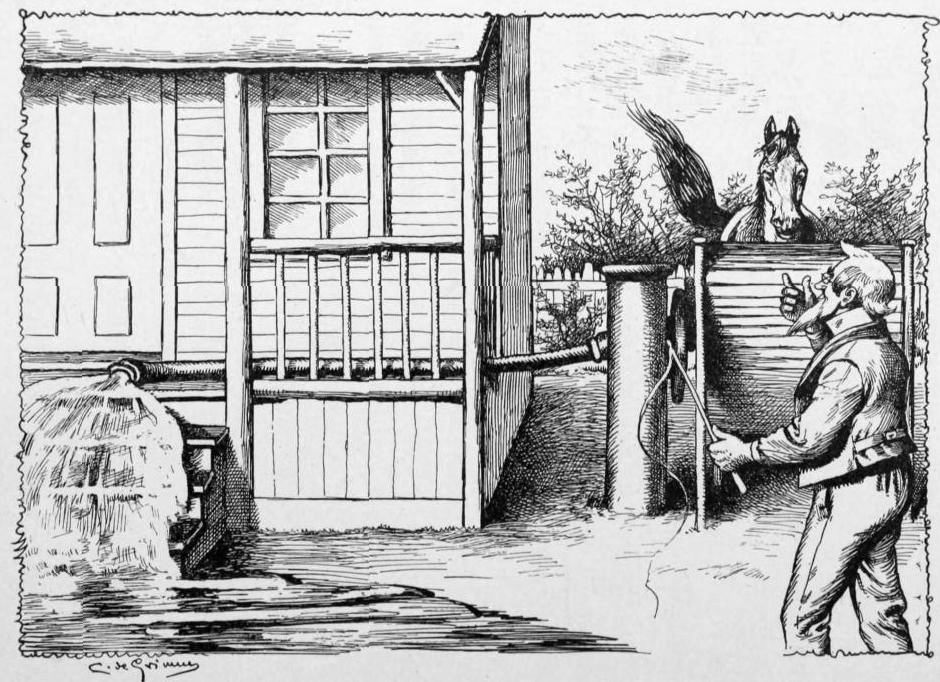

JOSIAH’S HOME-MADE WATERFALL.

“Where would you git your water?” sez I coldly.

“Wall,” sez he, a-holdin’ up the paper with quite a lot of figgers and marks on it, “I figgered it out that we might have a pipe go from the kitchen pump, cut a little hole in the thrasholt to let it go in, and there you would be.”

“And did you lay out,” sez I in frigid axents, “to have me stan’ there a-pumpin’ all day to supply your waterfall?”

His mean begun to fall a little—it had been triumphant—and he sez kinder meachin’—“You have to throw out your dish-water anyway, and you might’s well throw it on the steps as to throw it in the dreen.”

“Wall,” sez I, “a fountain a-runnin’ dish-water would be a beautiful spectacle, wouldn’t it, Josiah Allen?

“I guess it would astonish the eyes of the Jonesvillians, and their noses, too!”

“I didn’t mean that!” he hollered quite loud.

“What did you mean, then?” sez I.

He agin murmured sunthin’ about the pump, the cistern, and the old mair.

And I sez, “That poor old mair agin!” Sez I, “If I hadn’t broke it up, that mair wouldn’t live three days after we got home, with all you’d put on her, a-apein’ foreign idees, Josiah.”

“I hain’t been a-apein’, and you know it!”

But I went right on—“Even if you could make it work, how could we git into the house if the doorstep wuz turned into a waterfall?”

“Wall,” sez he, a-lookin’ up kinder cross, “I’ve hearn lots of times of havin’ the bottom sash of a winder hung on hinges, and goin’ in and out by ’em.”

“Wall,” sez I, “after you’d clumb up through the buttery winder onct or twict with a pail of milk in both hands, I guess you’d git sick of doorstep waterfalls!”

He see by the light of my calm, practical reasonin’ that his idee wuz visionary and couldn’t be carried out, but he wouldn’t own up to it—not he.

He jest jammed the paper down into his vest pocket, and snapped me up real sharp the next words I said to him.

He acted awful growety; but I didn’t care, I knew I wuz in the right on’t.

Wall, after goin’ through the brightest and most lovely garden you can imagine, you come into a place with huge rocks and cliffs, romantic shrubbery, massive ledges, and a waterfall fallin’ into a deep, dark basin, caverns, etc., and as you go round a corner, you come face to face with a huge rock that you think must have fell there. You think you will have to go back; but no! Do you think you will have to turn back for anything in this enchanted place? The hired man touches the rock, and it turns right away and lets you pass, and then you see that not only is the enchantin’ beauty of the place made, but the rough wildness of this spot.

One of the curous things in this place wuz a tree with kinder queer-lookin’ branches, and the hired man touched it somewhere, and water flowed out of every leaf and twig, turnin’ it into a fountain.

The conservatory is from one end to the other two hundred and seventy-six feet long, and broad enough to drive through it with a carriage and four horses, so you can imagine the wealth of beauty in it—orange-trees full of their glossy fruit, lemon-trees, feathery palm-trees fifty feet high, bamboos, cactuses, bananas, queer, broad, velvety leaves of every shape and color, and all of the flowers that ever wuz hearn on, and never wuz hearn on, it seems to me.

There are thirty other greenhousen, all runnin’ over with beauty of various kinds. Graperies seven hundred feet long, with the rich white and purple clusters hangin’ down in every direction. Peach housen, strawberry housen, apricot, mushroom, vegetable housen, in which every kind of vegetable is raised. Why, the kitchen-garden and greenhousen covers twenty acres. But there is no use of talkin’ any more—like Niagara, and the World’s Fair, you have got to see it to understand its vastness and its perfect beauty.

I wuz glad I’d seen it. I believe that even Martin wuz kinder took down off from the Mount of Self Esteem he always sets on, as he wandered through it.

He’d always prided himself quite a good deal of his home in the city, and it is palatial and grand. But what comparison would it bear to this? Not even—

“Like moonshine unto sunshine,

Or like water unto wine.”

No; it wuz like a small kerosene lamp unto sunshine. And he felt it, Martin did. He didn’t patronize anybody for as much as three quarters of an hour after he left there. He give the hired man a good-sized piece of money, for I see him. It wuz so big that the man turned fairly pale, and called Martin “Your Highness.” He sez—

“When will Your Highness return again?”

So we come off with flyin’ colors, after all.

Wall, seein’ that we wuz so near, Martin thought we’d ride over to Haddon Hall, only a few milds away. This is one of the fine old buildin’s of the Middle Ages. It stands on a rocky eminence above the River Wye; over the great arched entrance is the arms of the Vernon family, who occupied it for three hundred and fifty years.

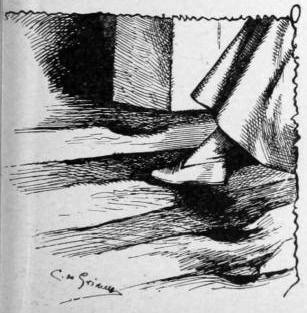

HER COMMON-SENSE SHOE.

As we passed in through a little door, cut in one of the broad sides of the gates, we see, on the rough stun thrasholt, the impression of a human foot, wore there by the innumerable feet of warriors, pilgrims, ladies, troubadors, children, kings, and queens, for all I know. Anyhow, she who wuz once Smith put her own common-sense shoe right into the worn footprint, and stood there, kinder on one foot, and had more’n eighty-seven emotions as she did so, and I d’no but eighty-nine or ninety.

I had a sight, anyway, as we went into the stun courtyard, ornamented with stun carvin’, into the interior.

Josiah didn’t take to it at all.

But, then, as I told him, what could you expect of a house where the folks had been away for several hundred years—any place would look kinder dreary.

But he sez, “Dum it all! when it wuz new, who’d like to have sech rough stun floors? And look at that fireplace in the kitchen, big enough to roast a hull ox. How could a man cut wood enough to keep that fire a-goin’?”

Sez I, “The man of the house didn’t have to do it at all, his vassals did it, Josiah.”

“Wall, he had to tend to it, and I’d ruther do the work any time than to keep a vassal a-goin’, that is, any vassal that I ever hired by the month, or day.”

But in the great banquettin’ hall, with its oak rafters and long table, where they feasted, at one end a little higher—for the quality, I spoze—he ketched sight of the minstrels’ gallery at one end. And sez he, his face lightin’ up, “The man of the house could git up there and sing while the rest wuz eatin’, if he wanted to, and nothin’ said about it.”

“Yes,” sez I pintedly, “if he could sing; but,” sez I, wantin’ to git his mind offen this unpleasant theme, sez I—

“I’d love dearly to see this table set out as it ust to be, and the noble and beautiful a-settin’ round it, with boars’ heads on the table, and great sides of beef, and gilded peacocks.”

“And jugs of ale and wine,” sez Josiah.

But I waved off that idee, but couldn’t wave it fur, for the beer cellars wuz a sight to behold. They must have been drunk a good deal of the time, jedgin’ from the accommodations for drinkin’.

Up the massive stun stairway we went into another big room, used as a dinin’-room by the later occupants of the Hall.

Here over the fireplace are the royal arms, and under them, in old English letters, the motto—

“Drede God, and honor the king.”

Goin’ up six heavey, oak, semicircular steps, we go into the ball-room, over a hundred feet long, with great bay-winders, out of which you see picters more beautiful than any that could be painted by the hand of man—perfect landscape of quiet country, silvery stream, rustic bridges, grand old parks, and the spire of the church from the distant village pintin’ up to the blue sky.

Then through other rooms with Gobelin tapestry on the walls, still holdin’ skripteral stories in its ancient folds.

Then through other rooms that are modern compared with the others, and have been used in the present century. Here, agin, in one of ’em we see Gobelin tapestry drapin’ the State bed.

Follerin’ the guide through a anty-room we come out into the garden on Dorothy Vernon’s Walk.

Under the tapestry is concealed doors and passages, as the guide showed us by pushin’ the folds aside, through which many a man or woman, drove by Fear or Love, or some other creeter, had rushed for refuge or secret meetin’.

The garden of Haddon Hall is picturesque and beautiful in the extreme.

Dorothy’s Walk, shaded by noble old trees, leads to the massive flights of marble steps, down which she hurried with beatin’ heart and flyin’ steps to meet her lover, Sir John Manners, while her friends were merry-makin’ in another part of the Hall, and never dreamed of her flight.

Haddon Hall by this means passed into the family of Rutland, who lived here till the first of this century. The Duke of Rutland keeps the place in its ancient form, much to the delight of those who love the old ways.