CHAPTER XVII.

JOSIAH HAS AN ADVENTURE.

Wall, Martin, who sometimes changes his mind, but don’t think he duz, always a-sayin’ that it shows weak-mindedness and is a trait belongin’ to wimmen (which I never feel like disputin’, knowin’ that my sect has in time past been known to be whifflin’; but so have men, too)—so it didn’t surprise me much when he said that instead of proceedin’ directly to the Lake District from here he thought we would go first to the home of Shakespeare. Sez he:

“I may be called to London any minute on business, and I feel that it will be expected of me to visit Shakespeare’s birthplace anyway.”

Sez Martin, with a thumb in both vest pockets, and a benine, patronizin’ look on his liniment—

“Shakespeare wrote a number of very creditable productions, and though I never had the time to spare from more important things to peruse his works—poems, I believe, mostly—yet I always love to encourage talent. I think it is becoming for solid men, for progressive, practical men, to encourage writers to a certain extent; and Shakespeare, as I am aware, has been very much talked of. I would be sorry to miss the chance of saying to those who inquire of me that I had been there, so I believe we will proceed there at once.”

“Wall,” I sez, “I shall be glad enough to go;” and Al Faizi looked tickled, too. He had read him, he said, in his own country.

And sez he to me, with his dark eyes all lit up, “To read Shakespeare is like looking into clear water and seeing your own face reflected in it, and earth, and mountain top, and over all the Heavens. And it is more than that,” sez he, “it is looking into the human mind and reading all its secrets—all the wonder and mystery of the soul; it is like looking at life, and death, and eternity.”

He wuz dretful riz up in his mind a-talkin’ about it, and he quoted Shakespeare quite often on our way to Stratford, and always in the right place, and he is generally so still, that I see, indeed, how he felt about him. Alice talked, too, quite a good deal about Shakespeare. And Al Faizi listened. Yes, he listened to Alice—poor creeter! And everybody blind as a bat but jest me.

Wall, we got there anon or a little before, and put up to the Red Horse Inn, a quaint, old-fashioned tarvern, but where we had everything for our comfort, and wuz waited on by as pretty a red-cheeked girl as I want to see.

A QUAINT, OLD-FASHIONED TARVERN.

A sight of emotions wuz rousted up in me as I sot in that tarvern, or walked through its old-fashioned, low-ceiled rooms and meditated on who had been under its ruff.

When rare Ben Jonson, and Drayton, and Garrick, and all of Shakespeare’s friends come down from London to visit him, of course they stopped here, and of course Shakespeare himself often and often come here—mebby too often for Miss Shakespeare’s feelin’s.

Much as I honor Shakespeare, I have to admit that he did stimulate a little too much—but, then, who hain’t got their failin’s? Why, Solomon, the very wisest man, had more wives than he ort to had.

Seein’, I spoze, that we wuz Americans, our supper that first night wuz served in Washington Irving’s room, as they call the room that he occupied, our own genial wit and poet. Mebby his words didn’t come in rhyme, but they had the soul of poetry, and quaint, sly wit, and good sense and good manners and everything.

I always sot store by Washington Irving. (I had got acquainted with him through Thomas J.)

Alice quoted a lot from Irving, and a lot from Shakespeare, while we wuz to the table, and I felt their presence in my heart.

Wall, I wuz so kinder beat out that night, that, as poets say, “I sought my couch” to once, a good-lookin’ oak bedstead, with a teester cloth overhead, and some curtains hangin’ down on each side.

The weariness I had gone through with that day, mixed in with the powders Mr. Morpheus keeps by him, brung on a sleep almost imegiately and to once. And I wuz sweetly a-dreamin’ of seein’ the Jonesville steeple a-pintin’ up through a ile paintin’ of cows and calves. Philury wuz a-peacefully milkin’ one of the cows, while Ury, a-settin’ on the steeple with a pail of skim milk, wuz a-tryin’ to bagon one of the calves to him, but a Madonna with a long beard poked at the calf with a sceptre and made it kick.

It wuz a sweet, tender dream of home, tinged slightly with the surroundin’s we had been surrounded by on our tower.

But anon as the Madonna and Philury changed into two gorgeous altar pieces, and Ury leaned near the calf and fed it out of a stained-glass winder—

Even at that very minute a sharp scream cut through the silence of night, like the ragged thrust of a bread knife through a loaf of light bread.

Once, twice, three times, did that cry ring out, and then I heard the sounds of rapid footsteps, and anon the door busted open, and my pardner rushed in and slammed it shet and clicked the bolt to.

And then he sunk down in his chair and almost buried his face in his hands.

I riz up on my piller, and sez I in agitated axents—

“What is the matter, Josiah?”

Sez he from out from under his hand, “I’ve done it now!”

“Done what?” sez I.

“Don’t ask me!” sez he, a-shudderin’ visibly; “it is nothin’ you want to know.”

But his words made me more and more determined to know the worst, as wuz nateral they should. And finally he said in a surly, cross way—

“Wall, if you must know, I’ve been into a woman’s room.”

“Been into a woman’s room!” sez I coldly; “what did you want in a woman’s room?”

“I didn’t want nothin’—Heaven knows I didn’t, only to git out agin.”

“Who wuz it?” sez I in stern axents.

“I d’no—she wuz a perfect stranger to me,” sez he, with his face still hid in his hand.

“Wuz she good-lookin’?” sez I in the same stern tones. I hain’t a mite jealous, as is well known, but I felt that I wanted to know the worst.

“Don’t ask me,” sez he; and he continued fiercely, “What business has a woman to be up a-ondressin’ herself at this time of night? Why wuzn’t she to bed and covered up?”

Sez he, a-growin’ more and more excited and fierce actin’—“I’m a-goin’ back and tell that woman that it is a shame and a disgrace to be up and ondressed at this time of night. Why wuzn’t her door locked, if she had to ondress?”

“What business wuz it of yours?” sez I. “Do you spoze she expected you to be a-prowlin’ round her room and a-prancin’ in, onbeknown to her?”

“Gracious Peter!” sez he in pitiful axents; “duz she think I wanted to be there?”

“Why did you go in, then?” sez I.

“Because I made a mistake!” he thundered out. “I thought it wuz our room. How should I know that there wuz a dum, red-headed fool there a-ondressin’ herself at this time of night? Why wuzn’t she abed—up, and skairin’ a man half to death?”

“If you’d kep’ out, Josiah, you’d have escaped,” sez I more softer like, for I see by his axents that he wuz a-sufferin’ from fear and the effects of the shock.

Sez I, “Be calm; accidents will happen, Josiah. Come to bed, and try to forgit it.”

SEZ HE, “I’M A-GOIN’ BACK—IT IS MY DUTY.”

“I won’t try!” sez he. “I’m a-goin’ back and give that dum fool and loonatick a piece of my mind. What henders some other man from walkin’ in?” Sez he, “I’m a-goin’ back—it is my duty!”

I riz up and laid holt of him, and sez I, “Do you stay where you be, Josiah Allen. I should think you’d done enough for one night.”

Sez he, “What henders Martin and Fazer from walkin’ in jest as I did, and bein’ skairt to death?”

Sez I, “Martin and Al Faizi know enough to take care of themselves, and it is your place to go to bed and behave yourself.”

“A-ondressin’ herself at this time of night!” he kep’ a-mutterin’ as he put his vest down on a chair.

“What are you a-doin’?” sez I.

“Wall, there hain’t a lot of strange wimmen round, is there?”

I see it wuz vain to dispute the pint. He acted deeply injured, and as if the woman had made a plot to skair him, and I had to gin up the idee of wringin’ any jestice out of his words and demeanors in the case.

But the next mornin’ he felt calmer, and didn’t seem to blame her so much, and admitted that she had to ondress, and said of his own accord that mebby he had been too hard on her.

But he wuzn’t quite reconciled, I could see, and felt deeply that he might have escaped the shock if she hadn’t ondressed.

Wall, our first visit wuz to Shakespeare’s birth-place. We sot out bright and early.

It is a long, old-fashioned-lookin’ house, with three gabriel ends in the ruff on front, and kinder criss-cross-lookin’, some like a big checker-board, the cross pieces of oak filled in with plaster, I should jedge.

We first went into the kitchen, with its wide, open fireplace, and how I felt when I thought that here, right here, in this spot, the immortal Shakespeare had often sot, with his feet and face burnin’ hot, and his back a-freezin’, as is the way with them old fireplaces!

But no matter how his body felt or didn’t feel, think of that mind, that soul that wuz caged in here between these narrer and queer-lookin’ walls. What visions them eager, bright eyes ust to see in the burnin’ flames! What shadders and shapes the clouds of smoke took as they floated up and away! How his soul follered ’em! How he sailed off into strange heights and depths, sech as no other writer ever did, or can, foller and explore! How the mind of the Infinite must have brooded over that little sleeper that lay over three hundred years ago in that low, shabby room upstairs—a small, dreary-lookin’ apartment, with the walls covered with the names of visitors and verses, etc.

We went up to it on a steep, narrer stairway. Martin had to take off his tall hat or he couldn’t have got in—I d’no whether he would or not if he hadn’t had to. I wuz proud to see that my pardner took off his hat the minute we got inside; I wuz proud of the reverence he showed for genius, and told him so.

But he said he forgot that it wuzn’t meetin’, it seemed some like it, he said, all dressed up at ten in the mornin’, and goin’ off all together.

After I spoke he wuz a-goin’ to put his hat on agin, but I sez—

“If you’ve blundered into reverential and noble ways, Josiah Allen, don’t, for pity sake, break it up.”

Of course my pardner always takes off his hat when goin’ into housen, visitin’, or callin’, or sech, or in our own residence. But on our travels, goin’ through big, cold buildin’s, dungeons, etc., he’s made a practice of keepin’ it on, bein’ bald, and sufferin’ in his scalp from cold.

But here, in this place, this hant of genius, I felt for about the first time sence I had been huntin’ antiquities, that I’d love to take off my own bunnet and dress-cap, but I spozed that the move would draw attention and call forth remarks, so I kep’ ’em on.

But my sperit knelt bareheaded and bowed itself down before this shrine of Wisdom and Genius, this earthly abode of one who showed what a grand and divine thing the human mind may be; who held the secret of all things common and transcendent—all things “that are dreamed of in our philosophy” and more—

This magician, who showed “what fools we mortals be,” and showed to what heights of wisdom men may attain—

Who held up his wonderful microscope and let mortals look through it into the inside of their own hearts and feelin’s and emotions. And who held up a lookin’-glass to Mom Nater, so she could see her old face in it, every beauty and every deformity—

Who plunged us into the depths of sorrerful and heart-breakin’ experience, bewitched us with his wit, and brung us up so clost to the divine good that we almost feel the beatin’ of the great heart of love.

Wonderful magician, indeed, and havin’ sech feelin’s for him for years and years (ketched a good deal from Thomas J., who admires him beyend any tellin’), I felt that it wuz strange indeed that she who wuz once Smith should stand right here in the place where he had once lived.

Al Faizi felt jest as I did, only more so—jest as still waters run deepest. I could talk with my companion yet, and the others, but he stood reverent and silent, and walked through the rooms like one in a dream, in which sech visions come that it “give us pause.”

But, as I say, I could still talk some—I seem to be made that way that conversation is hard to smother in my breast. Lots of wimmen are made jest so, and men too.

Martin wuz talkin’ fluently to Alice and Adrian as they went from spot to spot in the old house, and Martin wuz, I spozed, a-layin’ up a fount of memories that the public could tap, and valuable information would flow for their refreshin’.

But anon I missed my pardner; but even as my Thought wuz a-reachin’ after him, as it always must while it is yoked to my constant Heart, he come up to me with joy in his mean and a piece of paper in his hand, and sez he, with a glad and joyous axent, in which, too, pride wuz blendin’, about a third of each ingregient a-makin’ up his hull mean.

Sez he, “I have been a-writin’ a poem in the visitors’ book, Samantha, and I copied it off for you on a leaf out of my account book—I knew that you would want to see it, and then I shall keep the copy in my tin trunk with my money and deeds.”

I groaned instinctively, but suppressed it all I could as I sez—

“Let me know the worst to once! What have you writ?”

He proudly ondid the paper, and I read—

“I, Josiah,

Am settin’ by the fire,

Am right on the spot

Where Shakespeare sot;

I’m proud to be there,

Though I spoze, from what Samantha sez, that it hain’t the same chair.”

“There,” sez he proudly, as he folded up the paper, and put it into his portmoney. “There hain’t a verse here on these hull walls or on the visitors’ book that will compare with that.”

“No,” sez I coldly, “there hain’t—Heaven knows there hain’t.”

Sez he proudly, “It has three great qualities, Samantha—it is terse, melodious, and truthful. Shakespeare’s chair wuz sold two hundred years ago to a Russian princess, and they’ve kep’ on a-sellin’ the original chair several times sence, so how could it be here? If I’d been writin’ in prose, I should a said that it wuz a dum humbug!”

And here he paused reflectively and dreamily.

“I might have said sunthin’ strong and strikin’ here—

“‘It makes me mad as a June bug

To see ’em try to humbug.

‘JOSIAH.’

“You know that June bugs hum,” and he murmured dreamily, “humbug, and bughum; it would have been very ingenious, and I might say sunthin’ strong about ‘tire,’ to rhyme with ‘Josiah,’ about relicks bein’ made to order. ‘It makes me tired,’ you know, only have it come all in poetry,” sez he; “it would be dretful approposs.”

Sez I coldly, “What you mean by that, I don’t have any idee.”

“Why,” sez he, “I see it in The World; it is French, and it means to have anything come in appropriate—approposs, you know. I should have used it in my poem, but I couldn’t think of anything to rhyme with it but hoss.”

Sez I, “Tire is a good word to use in connection with your poetry. Everybody would appreciate it, and hail it with effusion.”

“But,” sez he with a wise air, “you have to be so careful in poetry. You can’t use strong phrases much, if any. And then, knowin’ that I wuz writin’ in the same book with kings, etc., I felt that it must be genteel and stylish. And I knew you always loved to be remembered, and so I brung your name in, Samantha.”

“Yes,” sez I, “you brung it in in sech a way as to hurt his folkses feelin’s as long as they make them chairs of hisen.”

“Wall,” sez he, “it looks well for pardners to remember each other, and it’s a rare quality, too.”

I felt that he wuz right, and didn’t dispute him, and sez he—

“Samantha, I wanted you to be jined with me on the pillow of fame. I don’t want to be anywhere where you hain’t, Samantha.”

His tenderness touched my heart, and I kep’ still and let him go on, only I merely remarked—

“As for its bein’ melodious, Josiah, your first line has got 2 words in it, and your last one seventeen.”

“Wall,” sez he, “that’s the way with great writers—they warm with their subject as they go on, and git all het up with inspiration. Jest think of Browning and Walt Whitman.”

Sez I, “Don’t go to comparin’ that verse of yourn with Browning. Why, folks know what you wuz a-writin’ about! Don’t compare yourself with Robert Browning.”

He see in a minute his deep mistake—he see that folks could find out what he’d undertook to write about.

“Wall, Walt Whitman,” sez he, “he writ jest as long and short lines. I’ve seen ’em to home in that ‘Leaves of Grass’ Thomas J. owns.”

“Wall, I wish your grass wuz to home, too,” sez I; “but,” sez I, a-sithin’ hard, “I’ve got to stand it, I spoze. But,” sez I warmly, “there hain’t a spot, from Egypt to Jonesville, but what I’d ruther had you broke out into poetry in than in this house.”

And I turned onto my heel and left him, feelin’ cheap as dirt about it, though I comforted myself with the thought that his poetry wuzn’t the only foolish lines writ there.

SHAKESPEARE’S GHOST READING THE EFFUSIONS ON THE WALLS OF HIS HOUSE.

I believe that if Shakespeare’s ghost comes back and hants this old spot—as it seems likely to spoze it duz—about the hardest thing it has to bear is to read the effusions writ all over the walls and in the visitors’ book, though some on ’em are quite good.

Prince Lucian writ a very good verse. But, then, he writ in it that—

“He shed jest one tear.”

How under the sun anybody can make calculations ahead on sheddin’ jest one tear, no more, no less, is a mystery to me, and it must have been jest out of one eye, and not the other.

But bein’ a Prince, I spoze he done it; but I never could. I couldn’t calculate closter than a dozen or twenty before I begun to cry, and I couldn’t cry with one eye and keep the other dry to save my life.

Our own Washington Irving writ quite a good verse, and so did the American Hackett—the best actor of some of Shakespeare’s characters.

Lots of actors have left their names in the room where the poet wuz born—Edmund Kean, Charles Kean, and a great many others. And in the visitors’ book you see writin’s from kings to chore-boys, and lines in every language—English, German, French, Chinese, Hebrew, Persian, Turkish, etc., etc., etc.

The Poet of the World has the world come to do honor to his memory.

Next to the thought that I wuz under the ruff that bent over the head of Shakespeare wuz to see the writin’ of some who had writ their names on the low walls.

Charles Dickens! Why, jest to look on that one name, writ by his own hand, would have been enough, if I had been to home, to furnished me with deep emotions for ten days. Nobody knows what my feelin’s have always been for that man.

It hain’t quite so fashionable to love Dickens now as it ust to be. The world has grown older and more genteel, and seems to prize more the writin’s it can’t understand—the vaguer ones and more cross like, and morbid, “Is Life Worth Living”—“No, it hain’t.”

“How to be Happy though Married.”

Ibsen, Tolstoi, etc., etc., etc., and so forth and so on.

But I lay out to like Dickens till, like Barkis, the high water comes, and—“I go out with the tide.”

So his name, the Master, I laid my hand on’t, and had ninety-seven emotions durin’ that time, and I presoom more, though truly I didn’t count ’em.

And Thackeray, who laughs with us over the weaknesses of humanity, yet once in a great while strikes sech a hard and onexpected blow onto our hearts and feelin’s, that we look right under that cynical veil he chose to wear, and see the great, tender heart of the man. His name, writ by his own hand, gin me powerful emotions, and sights on ’em.

Lord Byron’s name rousted me up some. Poor, onhappy, restless creeter! I wuz always sorry for him—sorry he wuz so mean and grand too—dretful grand. I spoze he wuz so onhappy that he couldn’t help lettin’ it run off the ends of his fingers sometimes onto the paper.

Some of his poetry uplifts you, like bein’ on a mountain-top in a storm, and some is like a calm moonlight night in the tropics, and still there is some on’t that I never felt willin’ that Josiah Allen should read—I felt that it would be resky to allow it. As I looked at his signature I instinctively sez over to myself a verse of hisen, that always seemed to be kinder open-hearted, and ownin’ up, and had a good deal of human nater in it. Some despair and some plain curosity—they always seem to touch a chord in everybody’s nater—I guess that most everybody sometimes feels jest about so, jest so kinder curous to know what is comin’ next—

“My whole life was a contest since the day

That gave me being—

And I at times have found the struggle hard,

And thought of shaking off my bonds of clay;

But now I fain would for a time survive,

If but to see what next can well arrive!”

Wall, he see the last thing arrive that we know anything about here. What come next, after he shet his eyes in Greece (dyin’ nobly, anyway) we can’t tell. But probble the one who formed that strange soul knew jest what it needed the most, and deserved.

Probble that was the—“The next thing that arrived.”

But I am indeed a-eppisodin’, and to resoom—

Then there wuz Sir Walter Scott, and Tennyson, and Longfellow, and everybody else, as you may say, who have distinguished themselves in literature and art, and lots of Lords and Ladies, but them I didn’t mind so much, knowin’ that for the most part that they had been born into their lofty places onbeknown to ’em, but the others had made the high pinnacles for themselves, and then stood up on ’em.

In another room we see lots of relicks of the past. Josiah nudged me once or twict a-lookin’ at ’em, I spoze to call attention to his poetry and his doubts. But I declined to be nudged, and never looked up at him at all, but kep’ my eye on the relicks.

One is a seal ring of Shakespeare’s, with his initials, W. S., tied together with a true lover’s knot. It wuz found near Stratford meetin’-house, twenty years ago and over, and is spozed to be really his ring, as he said sunthin’ in his will that shows that he had lost his seal ring.

Then there is a letter writ to Shakespeare by Richard Quincy, askin’ the loan of some money.

I sez to Josiah, “Whether he got it or not, if he could come back now he could sell that letter of hisen for enough to make him comfortable.”

“Yes,” sez Josiah; “I would give fifty cents for it myself, or seventy-five, if he would take it in provisions.”

“Hush!” sez I, “you couldn’t git it for that, for this letter, I feel, is genuine. It seems so nateral, borrowin’ money of a writer. Why,” sez I, “truth is stomped onto it.”

Then there wuz the desk that Shakespeare sot at when a boy. A rough, battered desk it wuz, with the lid lifted by leather hinges.

I sot down to it and leaned my head onto my hand and thought—thought—of how he felt when he wuz a-settin’ at it, and wondered if he had boyish joys or boyish sorrers jest like the rest of children. And if he scribbled poetry when he ort to be studyin’ his rithmetic, and whether old Miss Shakespeare, his ma, sent him off to school happy, with fond words and a kiss, or kinder mad from a spankin’.

To spank Shakespeare! My soul revolted from the thought.

Or whether, while he sot here, he studied his schoolmates and teachers with eyes that must have held some fur-seein’ wisdom in ’em even at that age, or whether his mind wuz all took up with goin’ in a-swimmin’ in the clear waters of Avon, or a-goin’ a huntin’, or a-nuttin’ in his rich neighbor’s woods, Sir Thomas Lucy, who looked down with sech disdain on William when a boy and a young man, and now whose only earthly chance of bein’ held in any remembrance is the fact that he misused Shakespeare.

But then mebby William wuz tryin’, boys are sometimes.

I wondered if while he wuz a-settin’ here where I sot any dreams of Anne Hathaway begun to come into his brain. She must have been about eighteen, allowin’ that William wuz ten; mebby some dreams of the pretty young girl hanted the boy’s vision, edgin’ themselves in between thoughts of play and study. But before long them little dreams wuz a-goin’ to rise up and push every other vision out of his mind.

And then there wuz Shakespeare’s jug, and the old sign of the Falcon—I hated to see ’em.

And some old deeds and documents relatin’ to his father’s property, from John Shackspere and Mary his wyffe, and a deed with Gilbert Shakspere’s autograph on it.

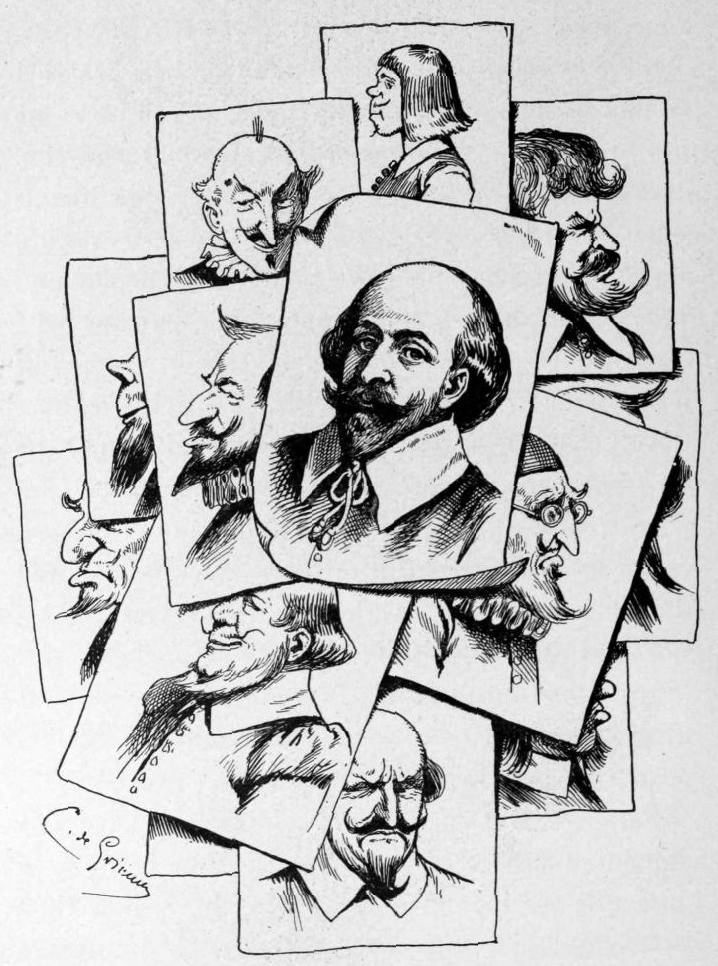

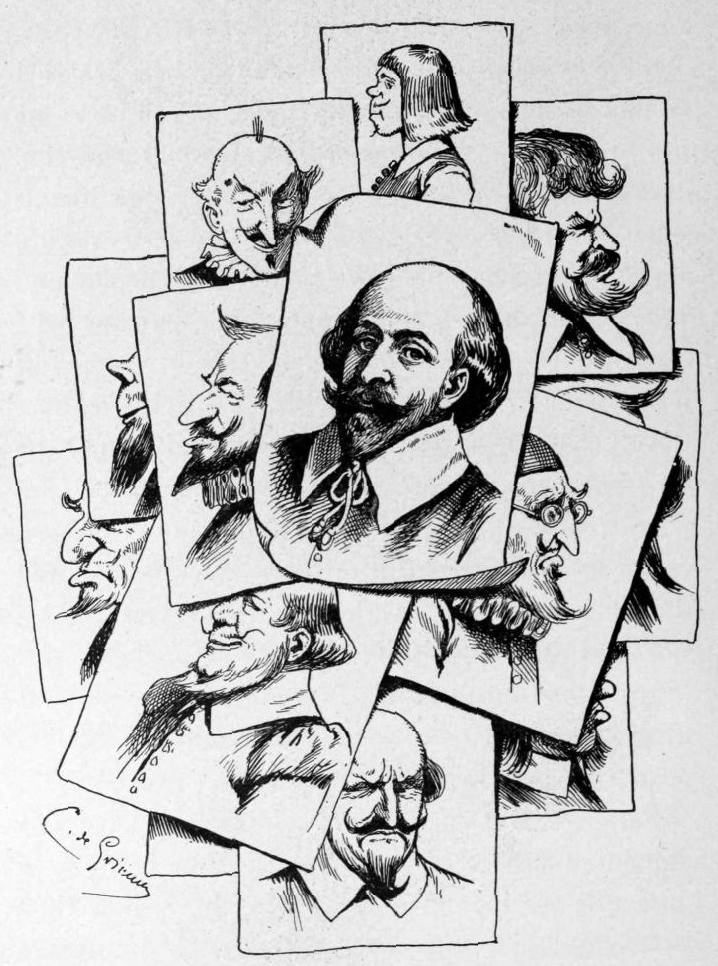

And lots of engravin’s of different places about Stratford, and a great many portraits of Shakespeare.

A GREAT MANY PORTRAITS OF SHAKESPEARE.

Poor creeter! if he and Columbus have got acquainted with each other where they be now, as I spoze it is nateral to think they have, how they must sympathize with each other over the numerous faces they wuz said to have had on this planet! Noble creeters, it wuz too bad, when they only had one apiece, and good, noble-lookin’ ones, I most know, or they wuz, anyway, when they got older, for Time, the sculptor, must have sculped some of their noble traits into their faces.

Martin and Alice bought quite a number of steroscopic views, and I bought a few, and would, though Josiah looked askance at me as I did it, and we left the cottage. But I laid my hand on the doorway as I went out, as though it wuz a shrine, as indeed it wuz.

Wall, havin’ seen the place where he wuz born, we naterally wanted to see the place where he is a-layin’, where “After life’s fitful fever he sleeps well,” havin’ “Ended the heartache, and all the natural ills that flesh is heir to.”

So we sot out for Holy Trinity Church. New Place, as it wuz called, where Shakespeare spent the last days of his life, and where his girl entertained Queen Henriette, wuz torn down in 1757 by its owner, who had moved away, and didn’t want to pay the heavey taxes levied on it. While livin’ there, he had cut down the mulberry-tree Shakespeare planted, because folks thronged into his garden so, and cut off twigs, etc., for relicks; so he cut it down.

It seems mean in him, and then, on the other hand, it would be hard for us to be broke in on any hour of the day, sometimes when we had a hard headache, and wanted to set quiet under our own vine and mulberry-tree, to have a gang of enthusiastick tourists come, and not only break up your quiet, but break off your branches over your achin’ head, and mebby recite Shakespeare right there in broad daylight, and declaim, and elocute, and act.

It would be tuff—tuff both ways. But the young folks of Stratford wuzn’t megum—they didn’t try to see on all sides, as she who wuz once Smith tries to do, so they used to pelt his winder with stuns and things, so he moved out. And much as I honor and revere Shakespeare, I feel kinder sorry for the man, mebby because nobody else seems to say a decent word for him. But I believe he see trouble, with taxes, tourists, elocution, and sech. And because our eyes are sot on a blazin’ sun that is shinin’ high in the Heavens, it hain’t no sign