CHAPTER XVIII.

SHOTTERY AND WARWICK CASTLE.

Wall, the next mornin’ we sot out bright and early for Shottery, Josiah feelin’ as peart as you please, and the two children’s faces lookin’ like roses. Al Faizi’s eyes wuz bent on the biggest and sweetest rose, as you may say, with a worshippin’ look, that nobody noticed but she who wuz once Smith.

We found the cottage a long, low buildin’, lookin’ as old as the hills, though, like ’em, there didn’t seem to be no signs of fallin’ down and decayin’.

They say it is in jest the condition it wuz when gentle Anne Hathaway lived here, and drawed William over here so often by the strong magnetism of love.

The walls wuz kinder criss-crossed, lookin’ some like Shakespeare’s cottage, and the ruff wuz kinder histed up in places, down towards the eaves, into gabriel ends. And some birds wuz playin’ and wheelin’ round the chimblys. They might have been to all appearance the very same birds that sang round the latticed winders of Anne’s room, and waked her up on summer mornin’s, a-sayin’ to her, as they wheeled round and round it, in the rosy dawn—

“Will is coming to-day to see you! Will loves you! Will loves you!”

I presoom the birds wuz relations to them very ones—grandchildren, “removed” a great number of times.

If birds keep a family tree and plume themselves on their ancestors (and trees and plumes comes nateral to ’em), I presoom they talk this over amongst themselves; mebby that wuz jest what they wuz a-talkin’ about that day, a-twitterin’ about legends a-flyin’ down from the past—

How the happy, eager-faced lover ust to come to see their pretty Anne, and how her heart wuz won, and she went out of the old house a happy bride with the man of her heart, who wuz not an illustrious man to her at all, but only Will, Will Shakespeare, the man she loved, and who loved her.

How they did chirp and talk sunthin’ over! I d’no what it wuz.

Inside wuz some old-fashioned furniture, amongst the rest a bed that ust to belong to Miss Shakespeare, she that wuz Anne Hathaway. Mebby it wuz the same bedstead that her pardner left her in his will.

“His second-best bed and bed furniture.”

It seems as if he hadn’t ort to done it; it seems as if she ort to had the best one. Howsumever, there might be reasons that I don’t know nothin’ of that influenced him. Mebby they’d had words over it; mebby she’d told him that she wouldn’t take it as a gift, and that he needn’t give it to her; mebby she thought it wuz extravagant in him to buy it, and throwed it in his face that as much as he paid for it, it wuz nothin’ but hens’ feathers, and the second-best bed, the one her ma had gin her, wuz as good agin and softer layin’.

I d’no, nor nobody don’t. Anyway, he willed it to her, and I presoom it wuz on this very bedstead it wuz put; it gin me queer emotions to look on’t, and a sight on ’em.

Wall, Martin sed that as the day wuz partially wasted, we might jest as well drive over and see Warwick Castle; it wuz only eight milds’ drive.

The old town of Warwick is about eighteen hundred years old, and dates back to the time of the Romans.

But, as Martin well sed, “Think of a town over eighteen hundred years old with only ten thousand inhabitants, and then,” sez he, a-leanin’ back in the carriage and puttin’ his thumbs in his vest pockets a-pityin’ and a-patronizin’ the Old World dretfully—

“Think of Chicago, about fifty years old and with a population of about forty hundred thousand”—he spread out the population a purpose. He owns lots of real estate in Chicago, and is always a-puffin’ it up.

Sez he, “They haven’t got public enterprise and push over here, as we have.”

But his tone kinder grated on my nerve somehow, and I spoke up and sez—

“They don’t base their reputation on a mob of folks, and beef and pork; they have sunthin’ more solider and more riz up like.”

But I’ll be hanged if I didn’t have to change my mind a little afterwards, of which more anon.

You see I had heard Thomas J. read a sight about the old Saxon earls of Warwick, and specially Guy Warwick in the time of Alfred the Great (you know the man that fried them pancakes and burnt ’em, and had other great reverses, but come out right in the end, as men always do who are willin’ to help wimmen in their housework).

I always bore strong on this great moral when Thomas J. would be a-readin’ these deeds to me (I thought he might jest as well wipe a few dishes for me once in a while as well as not). And he’d read “how Guy killed a Saxon giant nine feet tall, and a wild boar, and a green dragon, and killed an enormous cow.”

At the porter’s lodge we see the rib of that cow, and Josiah said, “You sed that they didn’t date back any of their greatness to beef; what do you call this? Why,” sez he, “Ury and I kill a cow almost every fall; nothin’ is said in history of it; you don’t set any more store by me.”

I see that I had done the man onjestice, and I sez tenderly, “You are a good provider of beef, Josiah, and always have been; but,” sez I, “this cow wuz probble twice the size of one of your Jerseys. You couldn’t wear that breastplate, or swing that great tiltin’-pole, or the enormous sword that hangs up there,” sez I, “you couldn’t move ’em hardly with both hands, and,” sez I, “look at that immense porridge-pot of hisen; you couldn’t eat that full of porridge, as he probble did.”

“YOU COULDN’T EAT THAT FULL OF PORRIDGE.”

“Try me!” sez he, earnestly—“jest try me, that’s all.” Sez he, “I could eat every spunful and ask for more.”

And there it wuzn’t much after noon. That man’s appetite is a wonder to me and has been ever sence I took it in charge. And foreign travel, which I thought mebby would kind o’ quell it down, only seems to whet it up to a sharper edge.

The way to the castle is through a large gateway, and then we go through a roadway which is cut through solid rock for more’n a hundred feet, and then when you come out, you suddenly git a full view of the grand old castle, with its strong walls and noble old Round towers.

The first is Guy’s Tower, one hundred and twenty-eight feet high, and has walls ten feet thick—jest think on’t! the walls further acrost than our best bedroom.

Then there is Cæsar’s Tower, eight hundred years old and one hundred and fifty feet high, and between these towers the gray, strong old castle walls, with slits in ’em for the bowmen to shoot their arrers out of, and portcullises and old moat, showin’ that the castle in its young days had everything for its comfort and defence. Enterin’ one of the arched gateways in the wall, you find yourself on the velvet grass and amongst the stately old trees of a spacious courtyard, with the ivy-covered walls and towers and battlements risin’ on every side of it.

We walked round up on them walls—clumb up into Guy’s Tower and looked off on a glorious landscape, as beautiful as any picter, and went down below Cæsar’s Tower into some dungeons; gloomy places of sorrer, filled even now with the atmosphere of pain and agonized memories.

The great hall, sixty-two feet by forty, with oak ceilin’ and walls darkened by time and covered with carvin’s, has firearms of all kinds, and splendid armor of all ages—English crossbows, wicked-lookin’ Italian rapiers, weepons of all kinds inlaid with gold and silver in the most elegant workmanship.

We see Prince Rupert’s armor, Cromwell’s helmet, a gun from the battlefield of Marston Moor. And, in fact, all round you you see the most elegant and curous curosities, and can look down the hull length of the grand apartments that open into each other, a length of three hundred and thirty feet—the red drawin’-room, the gilt drawin’-room, the cedar drawin’-room, etc., etc.

At the end of a little hall leadin’ from the great hall I see the noted picter of Charles 1st on horseback, with one hand on his side.

I declare, it actually seemed as if he wuz a-goin’ to ride right in here amongst us, it wuz so perfectly nateral. It wuz painted by Vandyke. I don’t see how Vandyke ever done it—I couldn’t.

The apartments are all furnished beautiful—beautiful. Cabinets, bronzes, exquisite old china, magnificent anteek furniture, and the most rare and beautiful picters are on every side—by Rubens, Sir Peter Lely, Hans Holbein, Salvator Rosa, Rembrandt, Vandyke, Guido, Andrea del Sarto, Teniers, Murillo, Paul Veronese. And beautiful marble busts by Chantrey, Powers, etc. There wuz a lovely table that once wuz owned by Marie Antoinette. And others had rarest vases on ’em, and wonderful enamelled work of glass and china, with raised figgers on ’em, made by floatin’ the metals in glass; nobody in the world knows now how to make ’em. One dish we see wuz worth one thousand pounds.

As I see this I nudged Josiah, and sez I, “When you think of what this dish is worth, hain’t you ashamed of standin’ out about that plate?” And he said—

“It wuz the sperit of the thing I looked at, mixin’ Shakespeare up with vittles; though,” sez he, “I would gladly eat now offen a angel or a seraphin; why,” sez he, “St. Peter himself wouldn’t dant me.”

“Wall,” sez I, “we’ll be havin’ dinner before long.” We laid out to eat at Warwick before we went back.

Sez I, “Look round you and let your soul grow by takin’ in these noble sights.” Sez I, “Look at them bronzes and tortoise-shell and ivory and mosaic.”

Sez he, “I’d swop the hull lot of ’em, if they belonged to me, for a plate of nut cakes or a bologna sassige. And I’d ruther see a good platter of pork and beans than the hull on ’em!”

I knew he wouldn’t complain so much alone, so I left him and sauntered round to look at the beautiful objects on every side.

In the state bedroom is the bed that belonged to Queen Anne, and the table and trunks that she used, also her picter.

In the grand dinin’ hall is a great sideboard, made from a oak that grew on the Kenilworth estate, so old that they spoze it wuz standin’ when Queen Elizabeth come here to the castle a-visitin’.

The carvin’s on it show the comin’ of Queen Elizabeth and her train, her meetin’ with sweet Amy Robsart in the grotto, the queen’s meetin’ with Leicester, etc., etc.

Jest as I wuz a-lookin’ at this and a-standin’ before it in deep thought, Martin come on out of the drawin’-room, and sez he—

“A wonderful display of art and virtu!” sez he.

My eye wuz bent on that sideboard, and I sez—

“I d’no as I’d call it a display of virtue—I don’t believe I would.”

I wuz sorry for Miss Leicester—sorry as a dog.

Though when I see the epitaph she put above that handsome, fascinatin’ mean creeter (her husband), put it over him her own self, when he wuzn’t by her to skair her and make her stand up for him as pardners will sometimes—I d’no as I wuz very sorry for her. Thinkses I, She either didn’t know enough to know what her pardner wuz up to, or else she wuz sech a fool she didn’t care about it. In either case I felt that my sympathy wuz wasted—of which epitaph more anon.

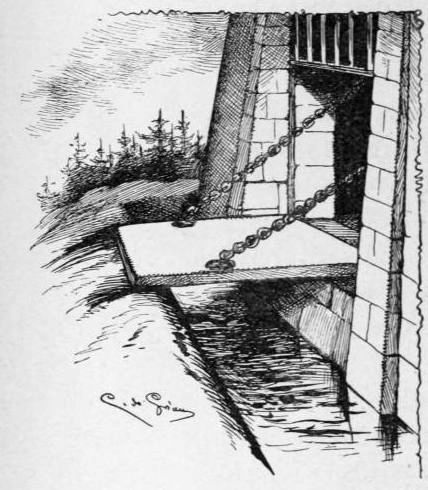

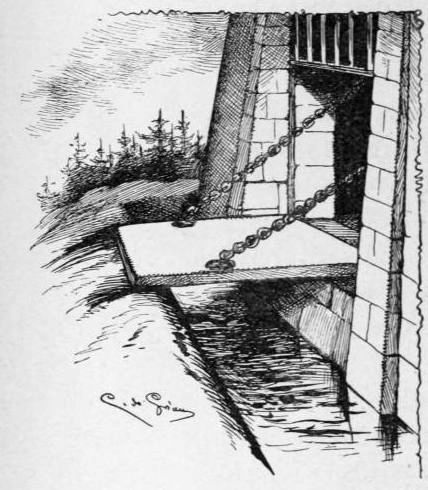

Wall, we went through a place in the wall they called a portcullis, and over a bridge called a moat.

“THE MORE I SEE OF MOATS, THE MORE DETERMINED I BE TO HAVE ONE ROUND OUR HOUSE.”

And Josiah nudged me here, and sez he, “The more I see of moats, the more determined I be to have one round our house.” Sez he, “How stylish it would be and how handy! When you see company comin’ you didn’t want, or peddlers or agents or anything, jest pull back your drawbridge, and there you’d be safe and sound.” Sez he, “I’ve wanted one for years, and now I’m bound on havin’ one.” Sez he, “Ury and I will start one the minute I git home.”

Sez I, “You won’t do any sech thing.”

“Why,” sez he, a-arguin’, “it would be a boon to you, Samantha; hain’t I hearn you groan when onexpected company driv up, and you wuz out of cookin’ or cleanin’ house or anything? All you’d have to do would be jest to speak to Ury or me, and jest as they wuz a-comin’ along, a-thinkin’ of dinner mebby, a-wonderin’ what you’d have—bang! would go the drawbridge, and they’d jest have to back up, and turn round and go home.”

“Yes,” sez I; “how could I face ’em the next Sunday in meetin’? It hain’t feasible,” sez I.

“Face ’em?” sez he; “if they said anything, tell ’em to start a moat of their own; tell ’em you couldn’t keep house without one.”

“Oh, shaw!” sez I; “come and look at this vase.”

And, indeed, we had entered a greenhouse full of the most beautiful flowers and rare plants, and wuz even then in front of the famous Warwick vase. It is a huge, round, white marble vase that holds one hundred and thirty-six gallons, with clusters of grapes and leaves and tendrils; and vine branches, exquisitely wrought, run round the top and form the two large handles, with other designs full of grace and beauty all wrought in it. How old this vase is nobody knows, but it wuz used by somebody probbly centuries before old Warwick Castle wuz ever thought on.

Who wuz it that drinked out of it? How did they look? How come it sunk in the bottom of the lake? I d’no, nor Josiah don’t.

It wuz found at the bottom of a lake near Tivoli by Sir William Hamilton, Ambassador then at the court of Naples.

I gazed pensively on the vine-clad spear of Mr. Bacchus carved on it, and sez I to Josiah—

“How true it is that that sharp spear that Mr. Bacchus brandishes is covered with beautiful vines and flowers at first; but it stabs,” sez I—“it stabs hard, and,” sez I, “who knows but somebody that had been pierced to the heart by that spear of hisen, a-reachin’ ’em mebby through the ruined life of some loved one—who knows but what he got so sick of seein’ them symbols of drinkin’ revels that he jest pitched it into the lake?”

“Keep on!” sez Josiah, “keep on! I believe you’d keep up your dum temperance talk if you wuz on the way to the scaffold.”

“That would be the time to preach it,” sez I; “scaffolds is jest what drinkin’ revels lead to, and if it wuz my last words, mebby folks would pay some attention to what I said.”

“Wall, wait till then,” sez he. “I have got to have a little rest. I am dyin’ for a little food, and if I git through this day alive I have got to be careful, and let my ears rest anyway.”

He did indeed look quite bad, and I sez soothin’ly—

“Wall, Martin will be for goin’ back before long now. He is gittin’ hungry himself; I heard him say so.”

We didn’t stop to but one more place on our way back to the tarvern where we had dinner, and that wuz to that old horsepital founded by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, in 1571. It wuz meant in the first place for one Master and twelve bretheren, the bretheren to be of the Earl’s servants, or his soldiers who had been injured in battle. But now they are appointed from Warwick and Gloucester, and have a comfortable livin’.

It wuz quite likely in Robert to build this horsepital—a old-fashioned-lookin’ place enough in 1895. But sech likely deeds as this couldn’t cover up his black performances.

The chapel is an elegant buildin’, built for a memorial to the great Earl of Warwick, the first in the Norman line, and his elaborate tomb is here.

But it wuz in this chapel where I see the epitaph of which I spoke more formerly. It is over the tomb of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, the one Queen Elizabeth thought so much on. There I see the epitaph I despised.

On the tomb are the recumbent figgers of Leicester and his pardner, the Countess Lettice. Probbly about the only time they wuz ever so nigh to each other without quarrellin’, and this epitaph sez, after givin’ all his titles—more’n enough of ’em—

“His most sorrowful wife Letitia, through a sense of conjugal love and fidelity, has put up this monument to the best and dearest of husbands.”

She must have been a fool, for besides his goin’s on with the queen—which would made me as jealous as a dog—a learned writer says—

“According to every appearance of probability, he poisoned his first wife, disowned his second, dishonored his third before he married her, and in order to marry her, murdered her first husband, while his only surviving son was a natural child by Lady Sheffield.”

“The best of husbands!” What wuz Lettice a-thinkin’ on? She’d no need to put his actin’s and cuttin’s up on a tombstun. I wouldn’t advised her to; but I should say to her—“Now, Lettice, you jest put onto that gravestun a good, plain Bible verse—‘The Lord be merciful to me, a sinner,’ or, ‘Now the weary are at rest,’” or sunthin’ like that—I should have convinced her. But, then, I wuzn’t there—I wuz born a few hundred years too late, and so it had to be; but it made me feel bad to see it. I want my sect to have a little self-respect.

Al Faizi is dretful well-read in history, and he took out that little book of hisen, and copied off the hull of the inscription on Leicester’s tomb, all the glowin’ eulogy of his glorious deeds, which he knew wuz false. He didn’t say nothin’, as usual, but looked quite a good deal as he writ.

I didn’t say nothin’ to him, but Josiah will att him once in a while about his writin’, and he sez now—

“What are you a-writin’ about, Fazer?”

He turned his dreamy, pleasant eyes onto us, and seemed to be lookin’ some distance through us and beyend us, and the light from the East winder fell warm on his face as he sez evasively—

“Your missionaries tell our people to always tell the truth—that we will be lost if we do not.”

“Wall,” sez Josiah, “that is true.”

Al Faizi didn’t reply to him, but kep’ on a-writin’.

Wall, a happy man wuz my pardner as we returned to the tarvern, and a good, refreshin’ meal of vittles wuz spread before him. He done jestice to it—full jestice—yes, indeed!

Wall, the next mornin’ we sot out for the Lake Deestrict, accordin’ to Martin’s first plan, which he’d changed some. Sez Martin, as we wuz talkin’ it over that evenin’—

“It would, perhaps, be expected of me to go on and visit Oxford.”

“Yes,” sez I warmly, “Thomas J. has read so much to me about Tom Brown at Oxford, it would be highly interestin’ to see the places Tom thought so much on.”

“Yes,” sez Alice with enthoosiasm, “and where Richard the Lion-hearted was born, and where Alfred the Great lived.”

Sez Josiah, “I wouldn’t give a cent to see where he lived. I despise fryin’ flap-jacks, and always did, and if a man undertakes to fry ’em, he ort to tend to ’em and not let ’em burn.”

But Alice went right on, “And think of being in the place which William the Conqueror invaded!”

“And,” sez Al Faizi, “where Latimer, and Ridley, and Cranmer were burned at the stake for their religion by Bloody Mary.”

It beat all how well-read that heathen is—he knows more than the schoolmaster at Jonesville, enough sight.

But sez Martin, with his thumbs inside of them armholes of hisen—

“It is not for any such trifling reasons that I would visit Oxford, but, as I say, it undoubtedly would be expected of me, if it was known at Oxford that I was so near, that I would give a little of my valuable time to them; for there, I have thought hard of sending my son to finish his education.

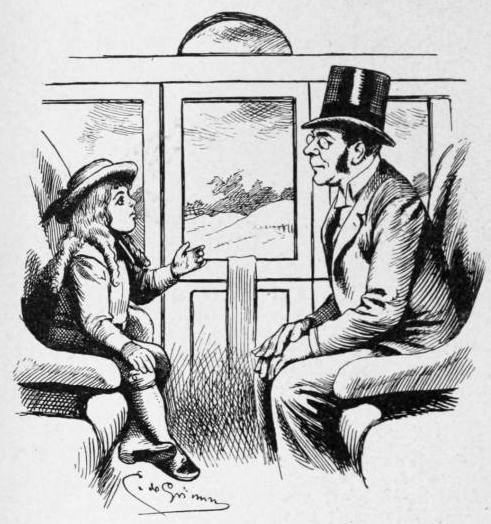

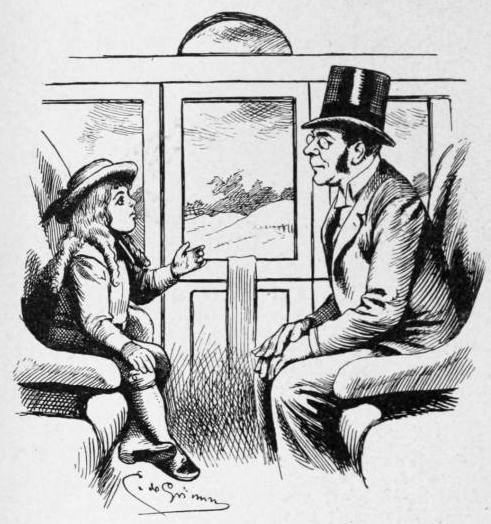

“For as you know, Cousin Samantha, my boy is to have the best and costliest education that money can give. His future is in the hands of one who will look out sharply for the very best and most valuable means of education. It is not as if he were a common child. But he is my little Partner—are you not, Adrian?” sez he fondly to the little boy, who wuz lookin’ dreamily out of the winder.

Adrian turned, and the gold of the settin’ sun wuz on his sweet face.

“Your father will look out for your future, little Partner; we will work together for your good, will we not, my boy?”

Mebby it wuz because I sot there so nigh—mebby it wuz the perfume of the English voyalets Alice had pinned into the front of my bask, jest like ’em I wore that day, but, anyway, some recollection seemed to take him back to that time at Jonesville, for he sez, jest as he did then—

“I AM GOING TO WORK FOR THE POOR.”

“I am going to work for the poor.”

“Ah, indeed!” sez Martin, smilin’, “and how will you do it, little Partner?”

Agin he turned his sweet face towards us, and agin the big, earnest eyes and sweet, serious mouth wuz gilded by the glowin’, yet sad smile of the sinkin’ sun.

And he sez simply, “I don’t quite know how, Father, but I know I shall work for them, and help them in some way.”

Wall, Martin dismissed the matter with a laugh, but I kep’ the words in my heart, and believed ’em. I believed truly that the Lord would lead him, and make him do His work.

Wall, I kinder wanted to visit Mugby Junction, as Dickens named Rugby Junction. It wuzn’t fur from Warwick, and I’d loved to seen it, and eat one of them sandwitches, and been glared at by the female in charge there, and her help, and seen her poor, browbeat husband and the Boy, but didn’t know as they wuz all alive.

And if they wuz, as Josiah well sed, sez he, “My stumick is bad enough now, without eatin’ leather sandwitches.”

And I sez, “I’d love to give ’em my recipe for good yeast bread, and I’d willin’ly tell ’em how to make delicious sandwitches, and not ask a cent for it.”

Sez I, “Take good minced chicken, or lamb, and a little mustard and sweet butter, and a pinch of minced onions and—”

But Josiah interrupted me, “They’d only look stunily at you if you offered your services; why,” sez he, “they always look as if they feel so much above you at our railroad stations to home, that you want to crawl into your hand-bag and git out of their way. They’d despise your overtoors.”

“Wall,” sez I, “my conscience would be clear, and travellers’ nightmairs wouldn’t be so frequent.”

But a bystander observed that they had good sandwitches there now.

Havin’ been turned round in their stuny and leather course, by Dickens, I spoze.

So we packed up our things and started in pretty good sperits for the Lake Deestrict.