CHAPTER XX.

THE ARRIVAL IN LONDON.

Martin, who owned, or pretty nigh owned, several railroads, wuz dretful talkative about the superior merits of our cars, etc. And, to tell the truth, these English cars did seem quite a good deal like ridin’ in a wagon, or a old-fashioned coach, where you set facin’ each other, and they wuz pretty low, made so as to not bump our heads when goin’ through covered bridges, I guess.

Of course, Martin paid for the best there wuz, and we had a hull car to ourselves, all cushioned and fixed off in the nicest manner, and after we all got in we felt very comfortable all alone by ourselves if we’d wanted to. And ever and anon a basket of good refreshments to refresh ourselves would be handed in to us. But it filled me with horrow to see bottles of beer, wine, etc., in every one of ’em, and I sez to myself—“Who and what did they spoze I wuz?”

I wuz indignant to think that they should dast to offer she that wuz once Samantha Smith bottles of intoxicants.

Josiah kinder hefted the bottle in our basket, and said dreamily sunthin’ about when you wuz in Rome of doin’ as the Romans did. But I sez to him coldly—

“Be you a deacon or be you not? Are you a member of the Temperance Society in Jonesville, or are you not?”

And he kinder wriggled round oneasy in his seat and laid the bottle down. If it hadn’t been for me, I tremble to think what would have been the result to Jonesville and the world at large.

Ever and anon the guide would walk along sideways by our winder and go the hull length of the train, for all I know a-seein’ to us. I don’t see what hendered him from fallin’ off. It wuz sunthin’ I wouldn’t have done for a dollar bill. I never wuz any hand to walk sideways, even on the ground.

But, howsumever, there wuzn’t any casualties reported.

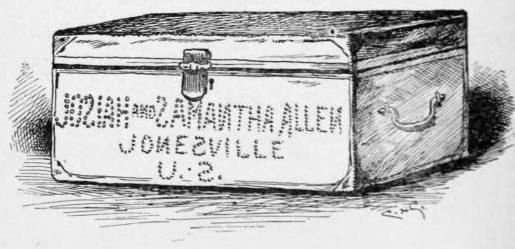

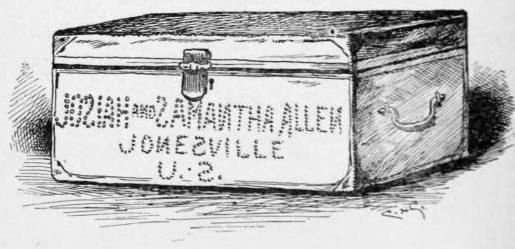

Another thing that did seem strange to us wuz that we didn’t have any checks for our baggage to take care on. That seems dretful queer to Americans to have to go out and hunt round and find our own trunks. Though we had no trouble with ourn, for it wuz a very valuable one, and easy to be recognized with the naked eye. It wuz a trunk that belonged to Father Allen, and made on honor, and it lasted him through his life, and then descended onto Josiah—and will, we think, descend, as good as new, onto Thomas Jefferson.

One reason it has wore so well is, I spoze, that Father Allen never took but one trip in his life with it, and that wuz up to Canada. That journey lasted him for a story all his days; he wuz looked upon with considerable or as a highly travelled man.

The trunk is covered with hair of a good gray color and trimmed off handsome with brass nails. And Josiah, to make sure of its not bein’ stole, writ our names in bright, brass-headed tacks. It took him quite a spell. He sed he believed in doin’ the fair thing by me, so it reads—

“JOSIAH AND SAMANTHA ALLEN.

JONESVILLE,

U. S.”

THEM LETTERS WUZ A STROKE OF GENIUS.

Them last letters he sed wuz a stroke of genius. He sed the English people would be so tickled when they see it, for they would see in a minute that he and me had really come over! We wuz there! “us!” Samantha and Josiah! and then, too, it would stand for the United States.

He made them two letters of a little bigger nails, but they wuz all good sized, and a very bright brass color.

And truly it did seem as if England wuz glad to have us there, for I don’t remember of seein’ a single Englishman that looked at that trunk that didn’t laugh when he see it, or smile warmly. Yes, they wuz glad enough to have us there.

Martin didn’t see the trunk until we arrove at the steamer, and it affected him different. He looked fairly stunted and browbeat when he sot his eyes on it; evidently he thought it wuz a pity to run the resk of jammin’ it, or gittin’ the nails rusty, for sez he:

“Good Heavens! let me get you a new trunk! It isn’t too late!” And he rushed off like a man half distracted.

But it wuz too late, for the bell rung in a minute, and we sot sail.

But Martin never see it durin’ that hull trip but he looked on it with that same look of or—a kind of a dark, questionin’ or.

Alice jest laughed when she see it. She liked its looks, we could see, though she didn’t come right out and say so.

But Adrian sed it wuz the most beautiful thing he ever saw in his life. And he beset Josiah to put his name on one of their trunks with the same kind of nails.

And Josiah, who had took a few along to repair damages in ourn, in case we should lose some of the nails, or some envious Englishman should steal ’em out, stood ready to do it.

But Martin broke it up. I guess he thought that Adrian wuz too young to go into sech extravagances. They had four trunks between ’em, but not so much luggage as the English carry round with ’em. They beat all, baskets, bundles, portmantys—as they call their trunks—and hat-boxes and rugs and bath-tubs.

The idee! What would we be thought on in America if we lugged round sech things. Josiah, who always hankers after style, sed he was most sorry we didn’t take our enamelled wash-dish. Sez he, “It would have looked dretful genteel;” sez he, “We could have lashed it to our trunk with some red cord, and it would have looked so stylish.”

“Oh, shaw!” sez I.

“Wall,” sez he, “when you’re in Rome, do as the Romans do, and,” sez he, “I’d love to let the English that carry round their bath-tubs see that ‘U. S.,’ the ones that own that trunk, know what gentility is and what style is.”

But I wouldn’t gin in to the idee, though he as good as sed that he stood ready to buy a new wash-dish for the venter.

But economy prevailed, not common sense, but jest closeness. I see in his mean that he wuz givin’ up the idee, as I told him that with the care I would give it the wash-dish we had would last for years and years.

Wall, we got to London in what ort to be the daytime, but it wuz as dark as pitch with fog, and how we wuz ever goin’ to git through them streets, full of blackness and roar, roar and blackness, wuz more’n I could tell.

I leaned back in that omnibus time and agin durin’ that trip, truly feelin’ that my hour had come.

As Josiah told me afterwards, in talkin’ it over—I wuz a-dwellin’ on my feelin’s durin’ the epock, and he wanted to outdo me, I guess, and sez he—

“I know jest how you felt, Samantha; I too felt, in the words of another, as if ‘every breath I drawed would be my next.’”

Sez I, “You meant your last.”

“Yes,” sez he, “my last; it wuz a dretful time.”

“Wall,” sez I, “I put my trust in Providence—a good deal of the time I did.”

“Yes,” sez he, “so did I. I wuz jest ground down to it that I had to.”

“Wall,” sez I, “less be thankful that we got out alive—out of that black, movin’, rumblin’ roar.”

We wuz talkin’ it over in our room that night, a good, comfortable room, with all the modern improvements. It wuz a hotel for Americans that Martin had gone to, and it wuz jest like the best of our American tarverns.

Josiah sez, when he see the bright lights in our room, “Thank Heaven, I won’t have to use my candles!”

He had hearn that folks had to furnish their own lights in England, so he’d lugged round a couple of taller candles, run in our own candle moulds to home.

A HULL SOAP-BOX FULL.

I told him not to, but he sed he wuzn’t goin’ to pay no high price for lights when we had a hull soap-box full under the suller stairs. So he had took ’em at the resk of spilin’ his dressin’-gown, as I told him.

“No, I don’t resk that,” sez he; “that is to the top of the trunk. The candles are packed down with my Sunday suit to the bottom of the trunk.”

I changed their position.

But his feelin’s for that dressin’-gown are simply idolatrous, as I tell him—specially the tossels.

And he said he “never thought of makin’ idols of ’em—worshippin’ a tossel!” sez he, scorfin’ly. But he duz think too much on’t.

Wall, the next mornin’ the fog seemed to be lowered a little. I could see the sun, or pretty nigh see it, which I felt wuz indeed a blessin’; and after a good breakfast we sot off on a excursion.

I had sed from the first minute London wuz talked on, that Westminster Abbey wuz my first gole, and the rest seemed to feel a good deal as I did. Al Faizi and Alice wuz dretful anxious to see it, and Martin sed—

He thought it wuz probble what would be expected of him, and if he wuz summoned home on account of his business, he said he must be able to say that he had been to Westminster Abbey, anyway.

So he engaged a big carriage, and we sot off, Josiah kinder laggin’ back and actin’ onwillin’. He had found a New York World in the readin’-room for the first time sence he left home, and he sed openly—

That he had ruther stay to home with his dressin’-gown on and read that paper than to see any Abbey that ever wuz born.

He thought it wuz some noted woman, and I wuz deeply touched by his preference, and cast-iron principle; but I explained, and would make him go. So we sot off.

Wall, the first view I got of that imposin’ edifice looked jest as nateral as could be; for Thomas J. has got a big photograph of it framed in his office, with the two great, high towers, 225 feet high, and the big Gothic winder between ’em, and the great Gothic door below. The buildin’ is a immense one; it is built in the form of a cross, and is more’n five hundred feet long.

I can tell you, I had a sight—a sight of emotions, and about as large sized ones as I ever had, as I stood inside, under them lofty arches, full of the mellow light of the stained-glass winders, and looked off down, down that long colonnade of pillows, at the end of which, fur off, is the chapel of Edward the Confessor.

This chapel is full of the tombs of kings and queens—Henry III., in brass, lyin’ on top of a huge porphery tomb; Edward I. and his queen, Eleanor, who sucked the poison from her husband’s wound in Palestine; and Queen Philippi, who put down a insurrection in Scotland, while her pardner, Edward III., wuz away from home.

Noble creeters! I wuz proud on ’em as I thought over their likely, riz-up deeds. I couldn’t have done more for my Josiah, and I felt it as I looked on ’em.

Wall, I said that the very first place I wanted to see wuz the place sacred to the Great Dead. So I went off kinder by myself, as I spozed, led by a guide, but the rest follered on after me.

Martin said that if a telegram should recall him home sudden, he spozed it would be expected of him, anyway, to say that he had stood by the monuments to Shakespeare, Dickens, Thackeray, etc., in Westminster Abbey. Sez he, “I have never read the poems of the last two gentlemen, but I hear that they are very creditable; so much so, that I have heard their names mentioned often, and I would like to say that I have stood by their remains.”

I didn’t say nothin’ to Martin, but the feelin’s as I stood right by the side of that man made a deep gulf that swep’ him fur off away from me, and swep’ me back into a life that seemed more real, almost, than my own.

Little fingers plucked at my gown, as it were, and, lookin’ down, I see the brave, patient face of Little Nell, and Tiny Tim, and David Copperfield, and the old-fashioned looks of little Paul Dombey, and Little Rowdey, Becky Sharp’s neglected boy; and little Clive Newcome’s sturdy figger wuz pushed away anon by the tall, slender figger that walked by his cousin Ethel Newcome’s side with a achin’ heart. I seemed to hear the Old Colonel saying “adsum” to the Heavenly roll-call.

Mrs. Gummidge’s melancholy voice, recallin’ the “old un’,” mingled with Peggotty’s comfortin’ talk and tender words to “Little Em’ly;” Mrs. Micawber, bearin’ the twins, passed on before me; Micawber, Dombey, Pecksniff, Little Dorrit’s patient form, Bella Wilfer’s handsome, wilful face went by me, a-lookin’ up, coquettish, but lovin’, into the sad, reasonable eyes of “Our Mutual Friend.”