CHAPTER XXI.

WESTMINSTER AND PARLIAMENT HOUSES.

I see Captain Cuttle and Bunsby fleein’ from Mrs. McStinger, and Wall’r Boy and his uncle, and Susan Nipper and Toots, and Mrs. Pipchin, and sweet Florence a-walkin’ by the Little Brother where the wild waves were talkin’ to him and the silver sails a-beckonin’ him over into a fur country—David Copperfield; Dora, the child wife; Agnes Wickfield, with her finger on her lips, and a-pintin’ upwards; dear Aunt Betsy Trotwood, and Oliver and Nicholas Nickleby; Mrs. Jellaby, with her dress onhooked and droppin’ papers with absent eyes, and Esther and Guardy, and Skimpole and the little Pardiggles—

How the crowd swep’ by me! It wuz a sight.

Ophelia passed by with her apron full of flowers, and she said to me, with a sad look out of her sweet dark eyes—

“Here is rosemary, I pray you, love, remember.”

Truly, I didn’t need her reminder—my soul wuz all rousted up and a-rememberin’.

I remembered the young feller she kep’ company with—yes, indeed! Hamlet, “the expectancy and rose of the fair state.” His shadder follered her clost, and I almost said to him with Horatio, “Good-night, sweet prince.”

But he looked kinder curous—he wuz a little off and acted, and, poor creeter! so wuz she, too; I felt to pity ’em both, and anon she seemed to be singin’ the song that Hamlet ust to sing to her when he wuz a-waitin’ on her:

“Doubt that the stars are fire,

Doubt that the sun doth move;

Believe that truth is a liar,

But never doubt that I love.”

She believed still in his constancy. She wuz a good deal out of her head.

Then Rosalind and Queen Catharine’s stately figger glided by; and eloquent Portia and Lady Macbeth a-holdin’ up her lamp, a-lightin’ her on to crime—the light a-shinin’ back into her dark, evil face—

And old King Lear, with faithful Cordelia a-holdin’ his tremblin’ old arms, and a-helpin’ him along.

Then, feelin’ pensive—Il Penseroso, I seemed to see John Milton’s blind eyes lookin’ into Paradise, and the Fairy Queen seemed to look down on us from the tablet of Spenser, and “Rare Ben Jonson,” Chaucer, John Dryden, Thomas Gray—

I wuz a-walkin’ back with him in the old church-yard—“Where the rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep”—

When Martin interrupted me, and sez he—“Gray, Thomas Gray, I suppose that is the father of Lady Jane Gray.”

I didn’t dispute him, but as I looked at him a-leanin’ back and a-feelin’ big, I allegored to myself—

“We don’t need to remember Micawber or Dombey; we’ve got a livin’ curosity with us.”

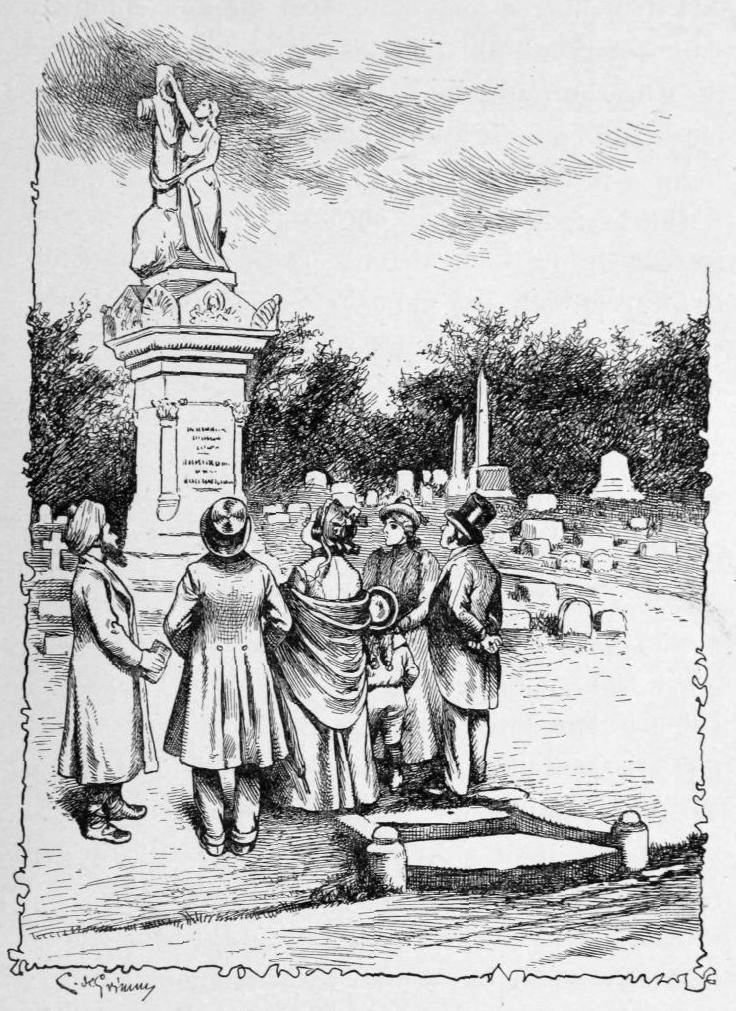

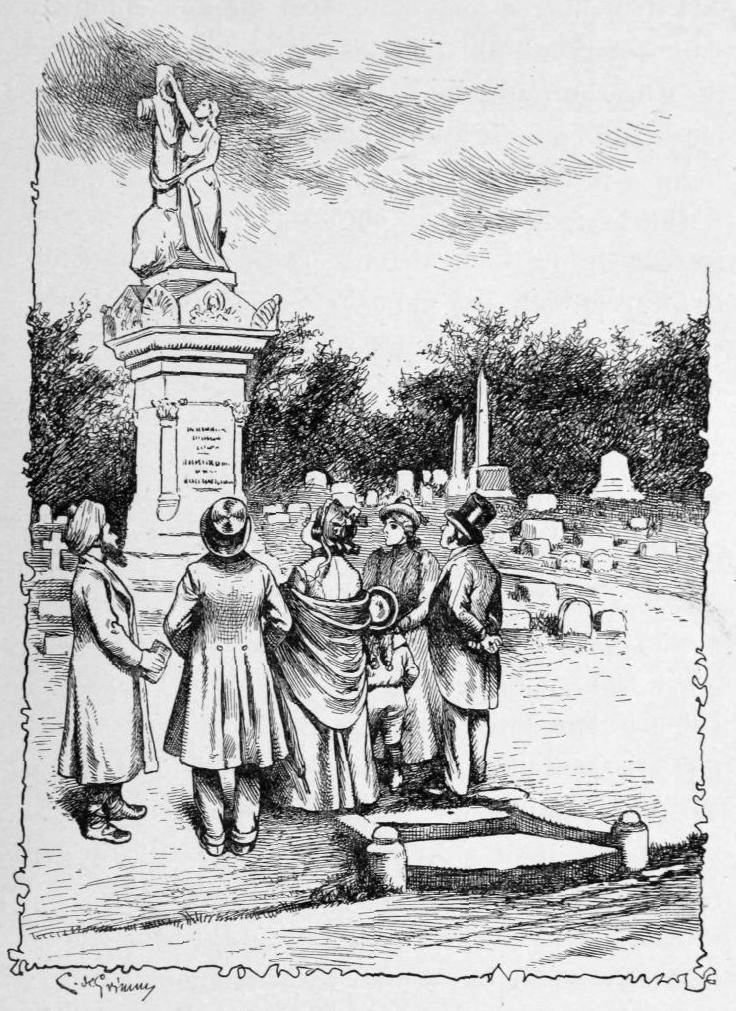

Al Faizi wuz deeply interested in the Poet’s Corner. He stood long and silently by the graves of the great dead, and his face wuz a deep mirror of his thoughts.

WE STOOD LONG AND SILENTLY BY THE GRAVES OF THE GREAT DEAD.

Alice wuz very much interested in ’em, too.

But as I stood by Goldsmith’s grave—a-seein’, with my mind’s eye, Mrs. Primrose and Olivia and the good Vicar a-moralizin’ at em—

I hearn Josiah say to Adrian—

“Oliver, goldsmith.” Sez he—“I spoze Mr. Oliver wuz the best goldsmith in England, or he wouldn’t be layin’ here. He probble made the crowns and septers they all have to wear in these monarkiel countries.”

I turned round, and sez I, “The metal that Goldsmith used wuz purer gold than that—it wuz the rare wealth of a faultless style.”

“That’s what I said,” sez Josiah—“stylish jewelry, and septers, and sech.”

But I explained it all out to Adrian, and kep’ him by me all I could.

Alice drawed my attention to the bust of Longfellow, our own poet, and my emotions swep’ me off quite a long ways, clear from this old Abbey to—

“Where descends from the Atlantic

The gigantic

Storm winds of the equinox.”

Yes, he seemed to bear me clear to the musical murmurs of Minnehaha, Laughing Water, and from Acadia to Spain. I travelled fur and wide.

And then there wuz the tomb of Thomas Campbell and Matthew Prior and James Watt and Mrs. Siddons. Not all in one place are these tablets and busts and monuments, but my mind seems to kinder gather ’em in together as I look back.

The most elegant chapel in the Abbey is that of Henry VII. Its noble arched ceilin’ is exquisitely ornamented and carved—flowers, vines, armorial designs, etc., etc., in almost bewilderin’ richness and profusion. Henry and his wife Elizabeth the last to rain of the House of York.

In this chapel is also the tomb of poor Mary, Queen of Scots, with her figger in alabaster on top of it.

If it wuzn’t in alabaster—if she wuz alive, and if the kings and queens wuz also alive and actin’—what a time there would be in that old Abbey!

If that exquisite body had agin that rare gift of magnetism—or, I d’no what it wuz, anyway, it wuz sunthin’ that drawed men to her despite their own will, and, it is needless to say, aginst their pardners’ wishes—what a time, what a time there would be!

How the emperors and kings and princes that now stood so still and demute would gather round her! How the wives would draw back and glare! And mebby some on ’em, bein’ quick-tempered, would throw their septers at her.

Poor creeter! mebby it’s jest as well that she is made of alabaster; for not fur from her is the tomb of Queen Elizabeth, a-layin’ down guarded by four lions.

She’d a-needed ’em, Lib would, if she’d a-expected to keep her lovers from a-follerin’ after Mary. She wuz a jealous creeter, and vain, although a middlin’ good calculator.

But Raleigh, and Leicester, etc., etc.—lions couldn’t a-kep’ ’em from the prettiest woman—no, indeed!

In the same vault is Bloody Mary, who burnt up about seventy folks a year durin’ her rain.

Al Faizi took out his little book with a cross on’t, and wrote quite a lot here, and he also did before Mary, Queen of Scots. I d’no, mebby he, too, bein’ a man, felt some of the subtle charm that surrounds her memory, even to-day, and keeps men from ever doin’ plain jestice to her, and always will, I spoze.

Not fur off is the restin’-place of the little princes murdered in the Tower by Richard III.

Al Faizi writ sunthin’ here, too, in his book—quite a lot.

There are nine chapels in the Abbey, each one full of the tombs of ’em whom the world has delighted to honor; and the guide told us that many a king and prince lay here who had not any memorial to mark his last sleep.

One of these wuz the “Merry Monarch,” Charles II. Among the great crowd who surrounded him, like a swarm of hungry insects, feedin’ upon him, and buzzin’ out their praise and compliments and loyalty to him, and flatterin’ his vices and weaknesses, not one of ’em thought enough of him to rare up the least little mark to his memory—

A deep lesson of the worthlessness of worldly praise or blame. A great contrast to this is the monument to Charles and John Wesley. They worked on all their lives, a-preachin’ and a-warnin’ aginst the vices of the great, as well as the humble, and here they have their monument amongst the royal dead.

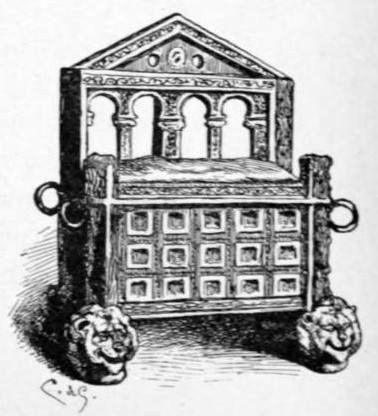

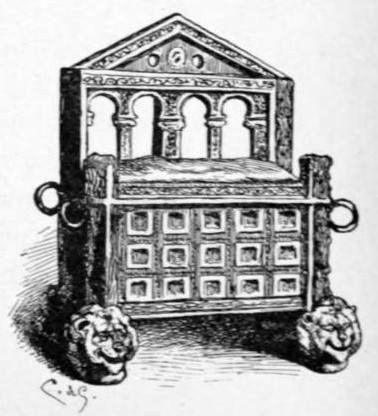

Another thing that interested me in the Abbey wuz the Coronation Chair, in which every sovereign in England, from Edward the Confessor down to Queen Victoria, has been crowned.

AN IMMENSE CHAIR, THE FOUR LEGS BEIN’ FOUR ANIMALS.

It is a immense chair, the four legs bein’ four animals—lions, I guess, though they looked kinder queer. But mebby they wuz a-thinkin’ who and what they wuz a-holdin’ up that made their hair stan’ out so kinder queer, and their tails curl up so.

Under the seat wuz a queer-lookin’ slab of stun, and they said it wuz the very stun Jacob had his head pillered on. It wuz carried back and forth by his descendants, and finally got to Ireland, where it wuz used at the Coronation of the Irish Kings.

Some say that if the one who wuz a-bein’ crowned wuz unworthy royal honors, the stun would groan, but kep’ still if it wuz the right one in the right place.

I should have thought it would have done considerable groanin’ in the centuries gone by—in the case of Henry VIII., for instance, etc., etc.

I don’t believe it groaned the last time it wuz used. No; as a female a-thinkin’ of a female, I wuz proud to contemplate the fact that most probble it never gin a single groan, or even a sithe, at that time.

Some say that wimmen can’t rule good, but hain’t Victoria rained well and rained long?

Yes, indeed!

Wall, we lingered in this venerable and intensely interestin’ place for a long time, and until the gnawin’s of hunger woke in my pardner’s inside, and he gin pitiful expressions of his inward oneasiness.

But Martin sed he must visit the Housen of Parliament. He sed that it would certainly be expected of him; so we went through Westminster Hall to the new Palace of Westminster, as the buildin’ is called.

The laws made here ort to be noble and big-sized, indeed, to correspond with the place they are made in. It covers eight acres of ground, has eleven hundred rooms, one hundred stairways, and eleven courts. It cost over fifteen millions, so they say.

But I d’no, I didn’t feel ashamed of our own Capitol at Washington when I see it. That is a good sizable buildin’, and made on honor, good enough and big enough to correspond with the laws made in it.

Yes, indeed!

Wall, Westminster Hall, that we went through to go to the House of Parliament, wuz dretful interestin’.

The great Hall of William Rufus wuz built first in 1097. Rufus wanted a great Hall, where he could hold banquets, and not feel crowded, and feel that he had air enough, and wuzn’t in any danger of hittin’ his head on the ceilin’, so he built this Hall.

It wuz partly burnt up once, but it has been repaired, so that it is a room now good enough for anybody, and big enough so’s the World and his wife and children could eat dinner here if they wanted to, or so it seemed.

It is three hundred feet long, seventy feet wide, and ninety feet high. The ruff overhead is carved into many beautiful forms, and is one of the largest in the world that has no columns or supports from below.

Glorious seens have been enacted in this Hall, as well as dretful ones. After the Hall wuz built over and beautified by Richard II., the very first public meetin’ held in this Hall wuz to take away his crown and septer and send him to prison.

Poor thing! after all he’d went through buildin’ it. I should thought them old timbers and jices would have creaked and groaned to have seen it go on.

I know well how I should have felt after we got our house altered over, and I’d jest got the parlor papered and carpeted and new curtains up, if I’d had to be dragged off and shet up, and let Sister Bobbett or Sister Henzy move in and take the comfort of it.

And I spoze Richard had feelin’s as well as myself, and the splendor of my parlor would mad me all the more to leave it, even if it shed a glory over the seen.

Charles I. wuz tried in Westminster Hall and condemned to death, and a few years later Oliver Cromwell was inaugerated in it Lord Protector of England.

He sot in that Royal Chair, which wuz took out of Westminster Abbey for the first and last time. The chair never groaned or took on any as I’ve ever hearn on, but I should have thought it would, not for reproof, but for sorrer. For only five years after that Cromwell died, and wuz buried in Westminster Abbey amongst its royal dead, and then three years later his body wuz took up and hanged on Tyburn by command of the king, and his head wuz displayed on the pinnacles of Westminster Hall with Bradshaw and Ireton.

Hangin’ a man who had been dead for three years, and for doin’ what he thought wuz right!

Al Faizi wrote quite a lot in his book here. He looked queer as he meditated on a civilized country committin’ sech barbarities.

They laid out to have the skulls remain up there on them pinnacles for thirty years, and some say they did, and some say Cromwell’s blew down durin’ a hard storm, and some of his descendants have got it to this day, and several of his skulls are in other places, so we hearn.

Poor creeter! He seemed to have as many heads as Columbus had faces. It beats all what them poor old fourfathers went through.

In this Hall Charles I. wuz condemned to die, and also Sir William Wallace, that Josiah and I felt so well acquainted with, havin’ formed his acquaintance and loved him through Thomas Jefferson and “The Scottish Chiefs.”

And Sir Thomas More, that witty, smart creeter—philosopher, statesman, and everything else—the favorite of Henry VIII., and who succeeded Cardinal Wolsey as Lord High Chancellor, but who lost Henry’s favor in his life, by not approvin’ of Henry’s stiddy practice of marryin’ wimmen and then cuttin’ their heads off, and marryin’ another and another, and so on and so on. Here the poor creeter had his trial.

Robert, Earl of Essex, wuz tried here and condemned; and so wuz Guy Fawkes, and the Earl of Stafford, and many, many, many others.

Wall, in the House of Parliament we see Parnell, the great helper for Irish rights. And it did my soul good to look on Joseph Arch, who wuz elected to Parliament as a representative of agricultural laborers.

He wuz a plough-boy, and his mother learnt him to read and write. She wuz a earnest Christian. Later he become a local preacher in the Methodist Meetin’-House. Afterwards, meditatin’ on their wrongs, he organized a union of agricultural laborers, and finally wuz elected to Parliament. He wuz sent from that deestrict where the Prince of Wales lives. And you would have thought that some richer and more aristocratic man would have been chose to stand for that place, so nigh to the British throne.

But no, a good man, a man of the people, wuz chose. The Prince of Wales never done a thing to break it up, so they say. He is quite a sensible, good-hearted creeter, the Prince is. Though, like the rest of the world, he has his failin’s.

Here we see Gladstone, that noble creeter. A man that will be revered and beloved and held dear to grateful hearts when lots of contemporary emperors and kings are forgot.

Yes, indeed!

The House of Lords is made up of lords temporal and lords spiritual—twenty-six lords spiritual, which are the Archbishops of Canterbury and York, and twenty-four Bishops, Dukes, Earls, Barons, etc., make up the lords temporal—they come into their places by the right of their titles, which fell onto ’em onbeknown to ’em. Here they set makin’ laws with their hats on.

Josiah drawed my attention to it, and sez he, “You’ve always tutored me so about takin’ off my hat everywhere and in every season. I’ve had sun-strokes and froze my scalp a number of times in carryin’ out your orders; but,” sez he, “I’ve made up my mind, Samantha, as to one thing, and you can’t change me.”

I have a deadly fear of his plans, and can’t help it—in fact, I have reason to, as dire experience has often showed me the dretful results flowin’ from ’em anon or oftener; so I waited with breathless dread to hear him expound his plan.

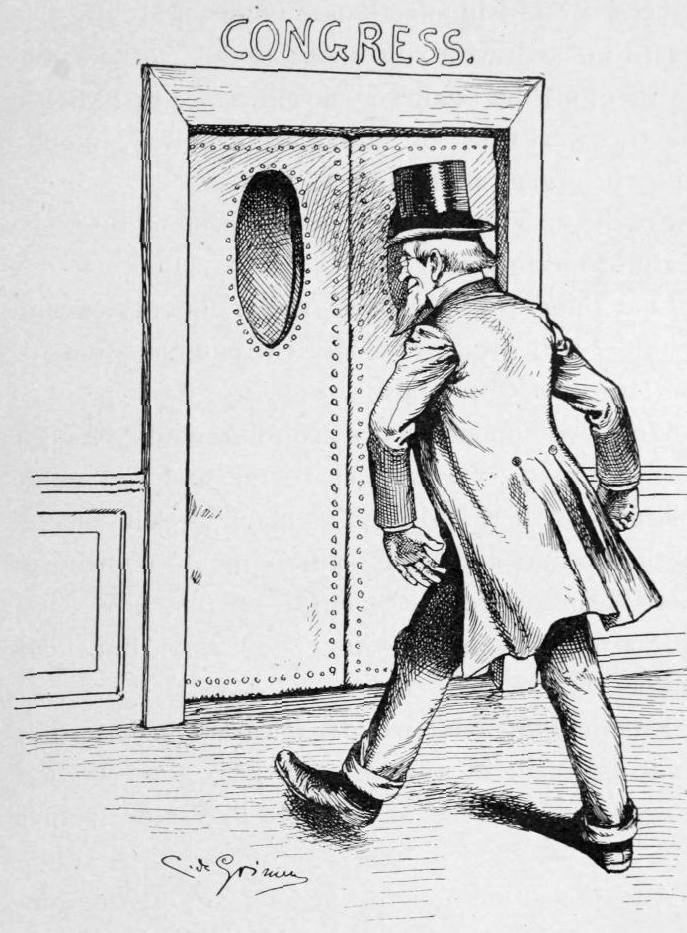

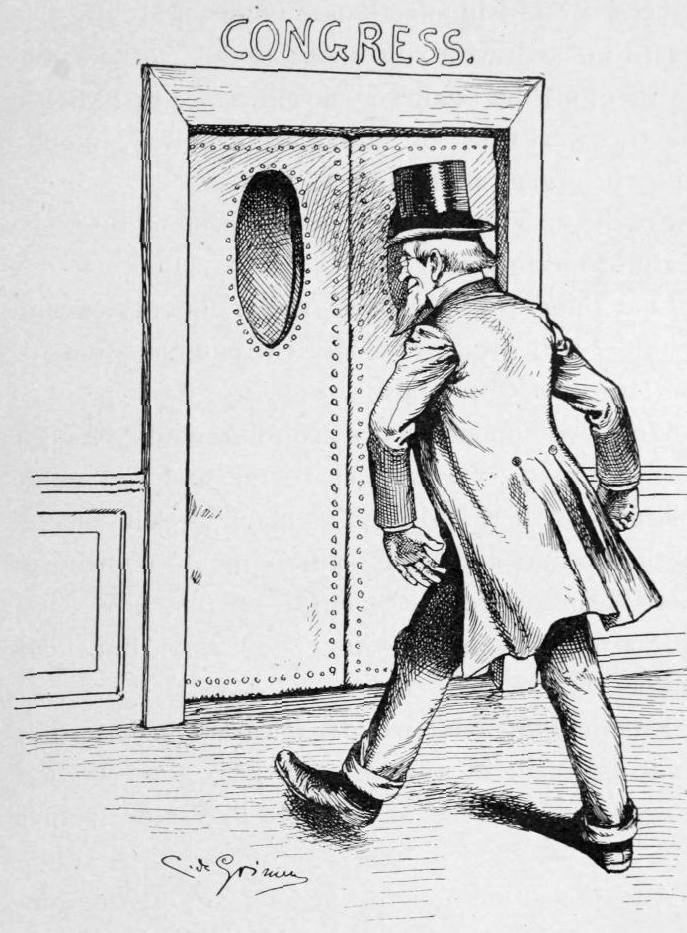

Sez he, “I’m bound on it. When I’m elected to Congress I’m goin’ to wear my hat the hull time I’m there; I hain’t a-goin’ to take it off only to go to bed; I calculate to have a good warm head the rest of my life.” Sez he, “If it’s proper for ’em, in their high station, it’s proper for me, when I git there.”

“WHEN I’M ELECTED TO CONGRESS I’M GOIN’ TO WEAR MY HAT THE HULL TIME.”

I thought a minute, and then sez I, “Wall, I guess I’m safe in not objectin’ to it.”

Sez he, “You mean by that, that I won’t git there, but you’ll see, mom. The minute I git home I’m a-goin’ to organize the farmers. I’ll organize Ury the first one, and then I’ll organize old Gowdey. Uncle Sime Bentley I can depend on.” Sez he, “If Arch and Burt and Macdonald, all on ’em workin’ men, can git into Parliament, what is to hender Josiah Allen from shinin’ in Congress?”

Sez I mildly, “Nater broke that up from the start.”

Sez he, “Do you mean that I can’t git in?”

Sez I, still more tenderly, “I alluded to shinin’, Josiah; but,” sez I soothin’ly, for I see that his liniment begun to darken—sez I, “I won’t say a word agin your wearin’ your hat under them circumstances.” Sez I in affectionate axents, “Mebby I’ve been too harsh with you about takin’ it off in cold weather; mebby I hain’t made allowance as I should for the weakness of the place exposed; mebby etiket has ruled me too clost.”

Sez he, “You and etiket has been almost the death of me time and agin.”

One thing that is sure to strike the tourist and beholder with wonder is the extreme smallness of the House of Commons.

How five hundred and sixty folks could ever git into that room is a wonder to me, and the guide told us that there had been as many as that a-standin’ there time and agin—a-standin’, of course, for there wuzn’t no room for ’em to set.

It struck Josiah, too, though, as usual, our meditations wuz fur different.

I methought, “No wonder laws hain’t what they ort to be, made in sech a tight place, by folks jest crowded and squoze in together like sardeens in a box.”

And Josiah methought out loud, “You thought, Samantha, that I didn’t allow half room enough in my new hen-house, and my brood of fowls have as much agin room accordin’ as these law-makers do.”

“Wall,” sez I, “there both on ’em kep’ in too clost quarters to do well.”

But truly I couldn’t break it up, for time and Martin didn’t give me no chance.