CHAPTER XXIX.

SAMANTHA CLIMBS THE RIGHI.

Our noble St. Lawrence could have took the Rhine in if she had been in need and adopted her, and let her run along with her, a-murmurin’ and a-babblin’ as children will, and nobody would have been the wiser only the old Saint herself.

And the Hudson is jest as beautiful. No old castles on the Rhine tower up so grand as Nater’s old homesteads, the Palisades, where she has dwelt, with Majesty, and Strength, and Sublimity, and Beauty for hired help, for so many centuries, and is a-livin’ there still in the same old place with the same help. Them who have eyes to see, can see her there right along day by day, and night by night, with her help all round her. Sometimes the risin’ and settin’ sun a-gildin’ their calm brows. And sometimes the big, serene moon a-standin’ over ’em as if lovin’ to linger with ’em. Their serene forwards a-shinin’ with the love they have for him—or her (I d’no whether to call the moon a him or a her. It is so kinder changeable, my first thought wuz to call it a him).

But to resoom. Yes, we found the Rhine beautiful. It runs along in my memory now like a beautiful paneramy right when I’m round the house a-doin’ up my mornin’s work, or night-times when I wake up ever or anon or oftener that fair picter onfolds in front of me—the ripplin’ waters, the shores sometimes smooth and grassy, with orchards and vineyards; fields of grain, with wimmen a-workin’ in ’em, as well as men; high rocky shores, with grim old castles perched up on the cliffs, tree-embowered; anon a wayside shrine, with the image of the Virgin a-lookin’ calmly on us tired voyagers, or the face of our Lord hallowin’ the spot, or the baby Christ in his Ma’s arms. It made the spots where we see ’em more lifted up, and made me feel kinder safer, though I knew it wuz only some wood and paint and glass it wuz made of. I spoze it wuz the memories and thoughts they invoked that seemed to hover over us some like wings.

How it sweeps onward in my mind—high cliffs three or four hundred feet high, with a picteresque old castle perched on it; anon a bridge of boats more’n a thousand feet long!

Then I see, a-lookin’ onto the paneramy, dog-teams, peasants, soldiers, beautiful towns, queer little villages, lovely villas, humble cottages, green grass, wavin’ trees, blue murmurin’ river. Ah, how it floats along in front of my foretop! Coblentz—Thurnberg—then the high cliff where the Siren ust to set and sing. I wonder if she sets there now? I mistrusted she’d kinder moved down into the vineyards. She sings there a sight, lurin’ the wine lovers right along to destruction.

Oberwesel, Castle Schonberg, and right acrost, like a faithful old pardner who has kep’ company for centuries, the towerin’ old walls of Gutenfels.

Right under my head-dress or nightcap the seen moves along. Anon I see the splendid old castle of Rheinstein way up above the river. Ehrenfel, vineyards, vineyards, with Lurlei hid amongst ’em, whether they believe it or not, and on the other, fur up, the Mouse Tower, where selfishness got its pay if it ever did.

Bingen we found, jest as Alice sed, a quiet little town, its marvellous beauty born in the homesick longin’ of the soldier who lay dyin’ in Algiers.

Johannesburg Castle would be dretful interestin’, standin’ up as it duz three or four hundred feet high, but the sights and sights of vineyards all round it made me feel bad, dretful. But I’ve had my say about that—sirens, etc., etc. What crazy acts would the wine make these surroundin’ folks do! That wuz a question I couldn’t answer, nor Josiah. I wish they wouldn’t make so much; I wish they would stop the mouth of Lurlei with good water, or cold tea, or sunthin’ or other—she’d act like another creeter if they did.

But truly I couldn’t make ’em stop by eppisodin’ or allegorin’.

On, on we went by islands, fortifications, palaces, villages.

I didn’t want to see Wiesbaden, I didn’t want to see card-playin’ and gamblin’ goin’ on—no, indeed.

But I did want to stop at Frankfort-on-the-Main, the birthplace of Goethe. And in thinkin’ on’t, I mekanically repeated over the words I’d heard Thomas J. rehearse a number of times—the homesick words of Mignon—

“Knowest thou the land where citron apples bloom,

And oranges like gold in leafy bloom?”

She wanted to go back home, Mignon did, she wanted to like a dog.

But Martin sed he didn’t know as anybody had ever made a specialty of visitin’ the birthplace of Goethe.

“And as for citron apples,” sez he, “your friend evidently made a mistake in writing about them; citrons grow on a vine; but,” sez he, “perhaps Goethe was in the grocer line and was recommending some new fruit.”

And I let it go so. Truly the author of “Wilhelm Meister” would have advised me to let it pass and go by.

But when Martin learned that Rothschild wuz born there, he sed that if he had had time he would have loved to visit that hallowed spot.

Martin thought he would stop and take a kind of a rest at Heidelberg, and my two legs and my pardner wuz glad enough of the rest—yes, indeed!

Martin sed that any traveller of note made a pint of visitin’ that spot, so it wuz on that account, I spoze, that we stopped. He sed he had seen a number of engravin’s of the place, and I told him I had too.

We stayed all night to a comfortable tarvern, and had a good supper and breakfust. Josiah admitted we had, though he sed—

“Samantha, it don’t taste like your breakfusts; oh, shall I ever partake of ’em agin in that blessed, blessed home?”

He suffers dretfully, that man duz. But I told him that we should soon be to home agin now, and to bear up.

Wall, Heidelberg Castle is a sight, a sight to see. All the picters we see of it in chromos and almanacks and sech don’t give you any idee of how grand, how vast it is.

Why, imagine a buildin’ all covered with carvin’s, and towers, and pinnakles, and with moats, and drawbridges, and dungeons, and courtyards, and banquet-halls, and decorations of all kinds, as big as from our house over to Deacon Henzy’s, and back round by Solomon Bobbettses, and acrost to Seth Shelmadine’s, and so on around the two cross-roads and back to our house.

Wall, reader, whether you believe it or not, it covers as much ground as that, and you well know how much ground that covers. Good land! it is enough to make anybody’s back ache to think of the days’ work it took to build it. But, then, it wuzn’t all done all in one job—it wuz begun a good many hundred years ago. They didn’t shirk their work, them old carpenters didn’t; the makers of summer hotels could take lessons of ’em in the matter of walls. It would make one of them paper wall makers swoon away to think of buildin’ a wall twenty feet thick.

I wish I had one of them rooms to take round with me summers on my towers. It would be impossible for the sound of snorers to penetrate into the apartment where one wuz vainly tryin’ to woo the Goddess of Sleep. And midnight snickerers would be futile to kill that Goddess with their giggle-pinted arrers.

Of course, a big part of this immense buildin’ is in ruins.

A handsome old stone platform or piazza that them old builders made half way up the castle walls I did want to see. It had everything it needed in the way of sculpters, vases, carved seats, etc. And the view, oh! my poor head-dress, it almost rises now as the paneramy sweeps through my foretop, it gives sech elevatin’ thoughts and emotions.

How fur off, how fur off you could see—towns, country, the blue Rhine, the mountains—oh, my soul! wuz it not a fair seen, a fair seen!

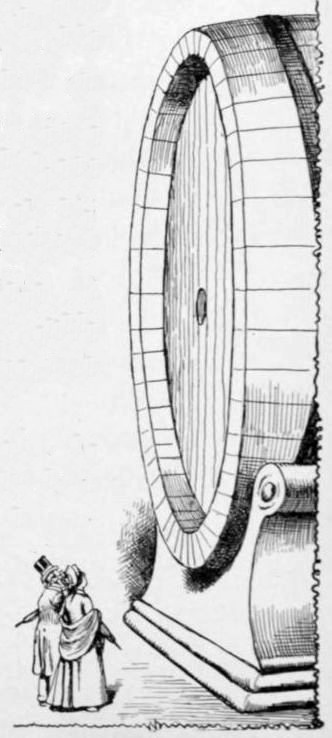

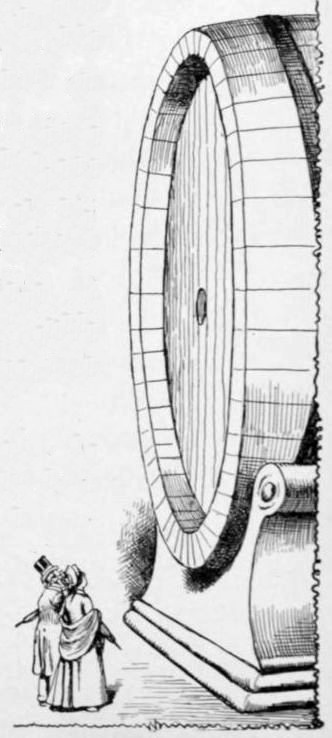

But the barrel, or, ruther, hogsit, to hold wine in, it jest madded me to see it. Would you believe it that the very worst old drunkard you ever see or hearn on would make a hogsit as big as the Jonesville tarvern to hold his liquor in?

A HOGSIT AS BIG AS THE JONESVILLE TARVERN.

Wall, it is, sir, full as big as Seth Widrigses tarvern. I won’t compare it to a meetin’-house, no, you can’t make me; the idee would be too sacrilegious to me.

It wuz as big as Seth Widrigses tarvern, barrooms, parlor, dinin’-room, bedrooms, ruff and all. It holds two hundred and thirty-six thousand bottles of wine.

The idee! it’s a burnin’ shame! How many fights can be shet up in it at one time—broken hearts, broken heads, murders, etc., etc., etc.!

I won’t talk about it another minute.

Wall, Martin sed that he spozed that it would be expected of him to go and see the Righi.

(I spozed that he thought that in his high, prominent position in society he ort to see some of the most riz-up places, so he settled on that.)

Mont Blanc he sed he should not endeavor to ascend, which wuz, indeed, a comfort to me; for how I wuz a-goin’ to git up on that steep, icy pinnakle with my heft and my rumatiz, to say nothin’ of my umbrell and my pardner, wuz more’n I knew. But if Martin had put his ultimatum on that we must go, I knew that we should have to make the venter.

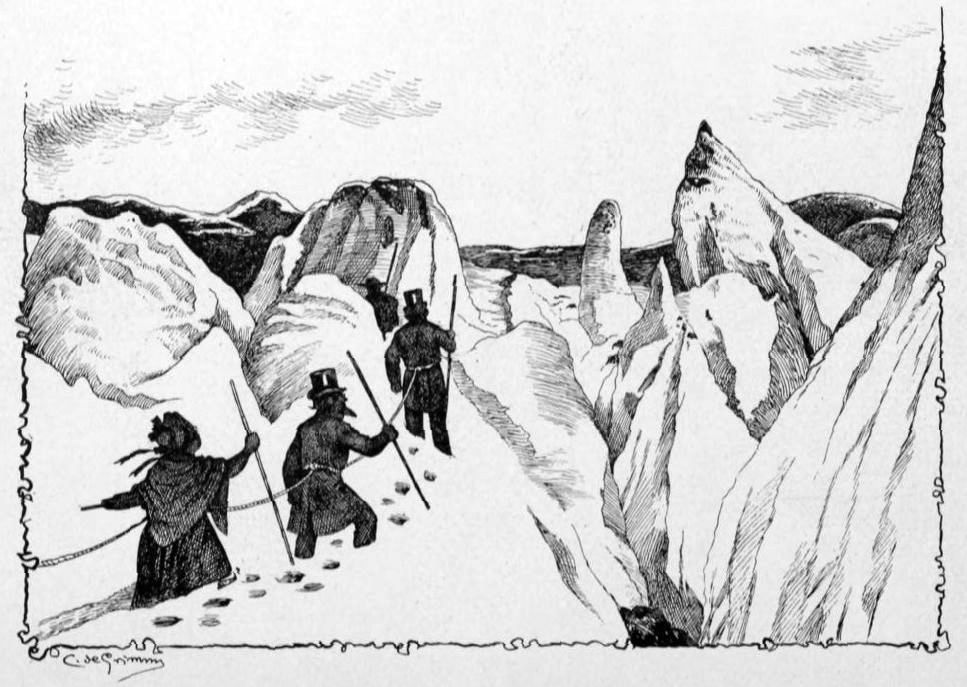

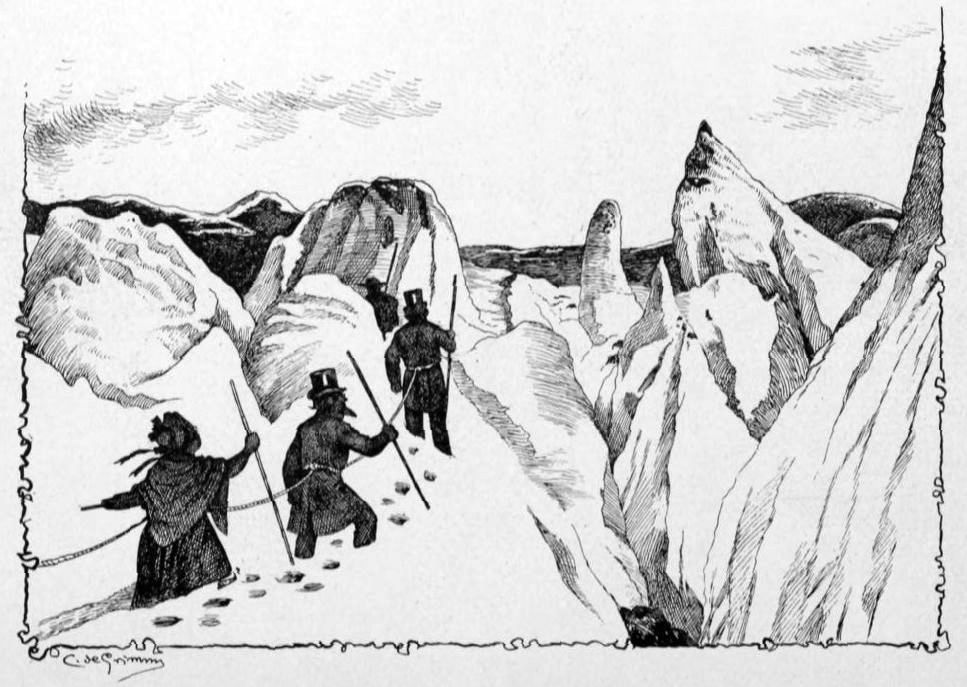

But he gin up the idee. He is a-gittin’ kinder short-winded himself, though he don’t own up to it. So we clumb the Righi. We rid up on that.

Josiah wuz all carried away with the idee of goin’ up that mountain, because the engine that took us up, instead of bein’ hitched on ahead to pull us up, wuz tackled on behind a-pushin’ us.

Sez he, “Samantha, it will be sech a uneek ride. What will Uncle Sime Bentley say to it, and the other Jonesvillians, when they hear on’t?”

There it wuz—fashion, fashion and display. From different standpints, he and Martin wuz jest alike.

But I knew that Josiah had some reason to be sot up by it, for that way of goin’ up mountains wuz a American idee at first.

Josiah took considerable comfort a-goin’ up (owin’ to the feelin’s I have depictered). But bein’ of sech a restless temperament, he soon announced that he wuz a-goin’ to git out and walk up. “For,” sez he, “I want to git there some time to-day, and I hain’t a-goin’ to creep along like a snail.”

But I seized him by his vest, and sez I—“Do you set still; it will tucker you all out to walk up six thousand feet!”

“Wall,” sez he, “I want to git there some time or ruther.”

We did indeed go slow, but sure; for in two hours’ time we arrove on the summit, and wuz ensconsed in a comfortable tarvern, from which, after Josiah had satisfied his yearnin’s for food, and the rest on us had refreshed ourselves with some refreshments, we sallied forth to see the grandeur as well as beauty of Nater; to behold what she can do when she humps herself, so to speak, and makes glory.

WE DID INDEED GO SLOW, BUT SURE; FOR IN TWO HOURS’ TIME WE ARROVE ON THE SUMMIT.

Wall, the view from the top of that mountain I can’t never describe. I stood perfectly spellbounded, and looked fur off down the mountain-side, and see cities, and villages, and farm-housen, and sparklin’ streams, and, fur down below, beautiful Lucerne and eight other lakes.

And on the off side the chain of snowy Alps a-meltin’ upwards into the blue of the summer sky, twelve thousand feet high, and on the nigh side forests, hills, mountains.

Oh, wuz it not a fair seen—a fair seen!

I stood perfectly lost and by the side of myself. The grandeur and beauty of the seen wuz so overwhelmin’ that, entirely onbeknown to myself, my bunnet had fell backward on my neck, and I stood bareheaded, jest as men do before a great heroine or hero. (I spoze it is jest as proper to call the Righi a female as a male; anyway, she stood up so dretful calm and serene it didn’t seem as if a male could hold that poster and calmness so early in the mornin’. You know, males are dretful restless and oneasy early in the mornin’. The work of the day kinder takes the tuck out of ’em, and they grow more sedater.)

But, anyway, I stood there bareheaded, jest as anybody ort to before the great Presence. The on-matchable grandeur of the seen—the sun a-beatin’ down onnoticed on my gray “crown of glory,” when I hearn a voice clost beside me, and the words kinder brung me back, for I had been quite a distance away from the real world of trouble and tourists and things.

The voice said—“For the land’s sake! I wouldn’t run the risk you do of tanning myself all up, for anything in the world.”

I wuz brung clear down, and I looked round, and I see standin’ clost to me a female, jedgin’ from her matronly form and her gray hair, that kinder meandered down on the neck of her ulster behind, of about my own age, or a little older, mebby. Yes, she wuz probble a number of years older, and though our hefts wuz jest about alike, she hadn’t got nigh so noble a figger.

She had two veils over her face besides a lace one—two braize veils, a green and a brown one, and carried a big umbrell, histed up to its full height, the umbrell a-lookin’ firm and decided, as if it calculated to shet off all the grandeur the braize veils didn’t make out to.

Sez she, as I slowly turned round and brung my spectacles to bear on her with a gray flame of wonder and surprise a-shinin’ through each one on ’em—

Sez she, “I wouldn’t tan my nose as you’re tanning yours for worlds like this.”

I sez mekanically, “Why, why not tan your nose?”

“Why, it would detract so from my looks; a nose adds so much to the looks of a human face,” sez she.

That sounded reasonable, and I sez, “Yes, that is so; a nose is necessary, both for beauty and for use; but,” sez I, “at our age a nose or two more or less, or a little tan on some on ’em hain’t a-goin’ to either make or break us—they won’t draw much attention,” sez I. “And even if they did, I expect to enjoy the society of my nose for quite a number of years yet, on towers and off on ’em, but this seen of grandeur I’m a-biddin’ good-bye to,” sez I, sadly—

“It is hail, and farwell, to me—I never expect to see it agin with these mortal eyes.” And I looked off on the lovely seen agin with all the rapter and sadness sech thoughts carry with ’em, when agin my rapt emotions wuz brung downward by the voice—

“Well, I know I wouldn’t run the risk you do of spoiling my complexion for thousands of worlds like this.” I felt that she needed roustin’ up and improvin’ upon, and I sez—

“Mom, I believe you’d enjoy Nater as much agin, if not more, if you’d forgit your complexion. Let your nose retire into the background, so to speak, and open the winders of your soul to the divine influences—look about and soar away, so to speak. And how you can do that under three veils and that umbrell is more’n I can tell.”

Sez she, confidentially, “I am dead tired of seeing things, anyway—I love to rest my eyeballs.”

“Then,” sez I, pityin’ly, “what be you up here on the Rigi for? What made you climb up so fur?”

“Well,” sez she, “I came with a party of Cook tourists, and you know just what they are for boasting; I’m not going to have them crow over me because they have been where I haven’t. Three of them are bed-sick at the hotel, but they can say with truth that they have been here. Two of the girls have to wear bandages over their eyes, and can’t see a thing, but they both have emulative Mas, who are bound that they shan’t be out-travelled by the rest of the girls, and so they are leading them round through Europe; blind as bats, but full of the true Cook fervor of travel.”

“THEY HAVE EMULATIVE MAS, WHO ARE BOUND THAT THEY SHAN’T BE OUT-TRAVELLED.”

“Oh, dear me!” sez I, “how bad it is for ’em!”

“No; they enjoy it. The doctor says all they need is quiet and rest to restore their eyesight, and they will have it when this cruel war is over and they get home. One of them is my own girl,” sez she, in a burst of confidence, “and I’m out here unknown to the rest; so my girl has outdone them, so to speak, for of course it is just the same as if she stood here where her Ma stands, in this be-a-u-ti-ful place, looking at this magnificent scenery.”

And she turned her wropped-up face towards the tarvern door, and faced round towards Josiah.

But truly she wuzn’t to blame, she couldn’t see through that envelopin’ drapery. The tarvern might have been a waterfall, and my Josiah a Alp for all she knew.

I felt quite curous, but consoled myself a-thinkin’ they wuz a-follerin’ their own goles, and would all set on ’em when they got home.

Wall, it wuz that very afternoon that I heard my first yodellin’—the melogious cry of the Alpine shepherds to one another. Clear and sweet it rung through the still air—Ye-o-lo-leo-leo-leo—

YE-O-LO-LEO-LEO-LEO—THE MELOGIOUS CRY OF THE ALPINE SHEPHERDS.

Melogious as any music you ever hearn, only sort o’ bell-like, and pecular. And while you stand spellbound and wantin’ to hear it agin the answer comes, sweet, fur away, clear—

Ye-a-oo-ye-ho-oo—

It wuz like nothin’ I ever hearn in my life, and yet seemed sort o’ familar to me, after all, as all true beauty in sight and sound duz seem to its devotees, he or she.

Wall, I wuz so lost in my own feelin’s of delight, and so carried away some distance by ’em, that I clean forgot that I wuz still in the flesh and still had a earthly pardner by the name of “Josiah.” But I wuz too soon fetched back to a realizin’ sense on’t.

For even as the sweet echoes wuz a-floatin’ back from peak to peak lingerin’ly, as if they wuz loth to let go on ’em, a voice spoke beside me—

“You’ll hear yodellin’ when we git home, Samantha Allen. Hereafter I shall never say ‘co-boss, co-boss’ to cows, or ‘co-day, co-day’ to sheep; after this I shall always yodel to ’em. Why,” sez he, “what a stir it will make in Jonesville! how the inhabitants will gather round me as I stand on the blackberry hill and yodel acrost to the creek paster! Why,” sez he, all carried away with the subject, as his nater is, “mebby I can learn Uncle Sime Bentley, so he can yodel back to me; mebby,” sez he, growin’ ambitious, “I shall yodel to Sister Bobbett and she that wuz Submit Tewksbury.”

Sez I coldly—“Do you confine your yodellin’ to dumb brutes, Josiah, who hain’t got sensibilities nor feelin’s to be woonded.”

“Mebby you hain’t willin’ I should yodel to Ury; but I’ll let you know I shall anyway, mom!”

“Wall,” sez I, “he is used to your performances; he won’t mind ’em so much.”

I knew it wuzn’t best to draw the string too tight; I knew I couldn’t break up his yodellin’ out to the barn, or round, when I wuzn’t in sight, and I felt that I would be glad to confine it to dumb brutes, and Ury, and sech.

Wall, anon, after passin’ through lovely seens—lovely ones, we found ourselves on beautiful Lake Lucerne, the most beautiful lake in Switzerland, or the hull world, for all I know—beautiful, beautiful for situation it is. You could spend weeks a-admirin’ the lovely views, and then begin agin and keep it up for years.

And before long we found ourselves, much to my pardner’s relief, in a good tarvern with a long Swiss name, that I always forgit, and called it to myself “The Swizzler,” which wuz jest as good so fur as I wuz concerned.

We didn’t stay here long, owin’ to Martin’s pecular views. But we hearn the organ in the old cathedral, and I wuz carried fur away from myself into the land of happiness, love, and peace, into the realm—where is it?—that lays so nigh to us, that a burst of glorious music will sweep us right into its gates, but so fur off that we hain’t never ketched a glimpse of its glorified mountains with our nateral eyes.

Al Faizi wuz carried into that same realm, too, I could see by his mean, and the rest on ’em wuz carried off wherever their nateral bent lay—Alice into the land of Love and Hope, Martin into the Stock Exchange mebby, where the roar of its bulls and bears drownded out the sound of the organ’s grand, melancholy voice.

LISTENING TO THE ORGAN’S GRAND, MELANCHOLY VOICE.

And Josiah, wall, mebby he wuz a-settin’ agin to a full dinner table in Jonesville, with Deacon Sypher and Drusilly and some of the other bretheren and sistern a-hangin’ breathless onto his adventers.

I d’no, I’ve only guessed at their emotions, but mine wuz a sight to see as the liquid waves of melody swep’ round me, and swep’ me along with it.

And then we see the Lion of Lucerne, a-layin’ there carved out of solid rock, in memory of the Swiss Guard, who fell defendin’ the Tuilleries in 1792. It wuz carved by Thorwaldsen, the great Danish sculptor, and is a noble and impressive sight. There it lay in a beautiful grotto, with water tricklin’ all round it, some as if the hull country wuz a-sheddin’ tears over them poor young men that perished in their prime. It lay stretched out, its hull length of twenty-eight feet, a-holdin’ in its paws the shield of France and some flower de luce—France is jest sot on them poseys, and I always liked them myself; I’ve got a big root of ’em under my bedroom winder at home in Jonesville.

I thought considerable in our short sojourn at Lucerne about William Tell, whose exploits with Gessler, apples, etc., took place in that vicinity (though I’ve hearn tell that Tell hain’t the creeter they tell on).

I THOUGHT CONSIDERABLE ABOUT WILLIAM TELL AND HIS EXPLOITS WITH GESSLER, APPLES, ETC.

But I always loved to read about him, and I always did kinder love to believe in things that ort to be true, if they hain’t—about liberty, freedom, and sech. Anyhow, he has got a high chapel built to him—mebby like some other popular idees, that haint got no greater foundation in solid truth.

Though, agin, what is truth?

Hard question.

Wall, our way on to Lake Geneva wuz like a dream of glory and grandeur, full of mountain peaks, green and snow-clad, and flashin’ waterfalls, with little side dreams of sweet green valleys—“sweet fields arrayed in livin’ green”—quaint villages, cosey little housen, swift dashin’ waterways, and gently flowin’ rivers.

Interlaken, Freiburg, Lausanne, how they look out of the paneramy at me when I shet my eyes in the Jonesville meetin’-house or anywhere, and onto the blue lake that Byron writ so much about.

Alice had beset her Pa to take her to Castle Chillon. And I had strange feelin’s, I can tell you, as I walked down the road with Josiah Allen by my side—from Jonesville meetin’-house to the Castle of Chillon—what a leap! Could Fancy cut up any stranger? I spozed we should have to take a boat to reach it, and so they did in old times, but now the water has filled in so, that, like the Israelites, we passed over dry shod.

The castle is over a thousand years old. Some say the Lake Dwellers built it, and in talkin’ about them queer creeters, who dwelt a thousand years ago in housen built up on posts stuck in the water, I had another trouble with my too ardent and susceptible pardner. Sez he—

“Samantha, what a beautiful way of livin’ that would be—how cool and pleasant in summer weather, and so handy; no luggin’ in water to fill the tank, no pumpin’, jest lean right out of the buttery winder and draw in a pailful, and then how easy to lower the milk in the water to cool. Why, we could have the milk-room built jest below the surface, and set the milk pans right into the lake, as it were. What butter we could make, how it would be sought for! And then the idee of settin’ in your own back door and fishin’ for pike and sturgeons, draw ’em right up and land ’em on the kitchen table, not a foot off from the briler. How convenient! And bathin’ now, you’re always a-tewin’ at me about it—washin’ my feet, it’s always a job—but now jest cut a little hole in the bedroom floor, and with a towel there you are. I’ll commence a house out on our pond the minute I git home for a summer retreat, no mowin’ door-yards, no fences to keep up, no gates to be onhingin’; why, I’d renew my age there, Samantha. And then think of the profit in the extra butter, etc.”

“How would it be about milkin’ the cows?” sez I. I see he hadn’t thought of that or anythin’ else practical, but he’d been jest carried away by the novel and the new.

But he wouldn’t give in, men have such doggy obstinacy. Sez he—

“Why, learn ’em to swim; begin when they’re yearlin’s, learn ’em to strike right out and swim up to the milk-house, hitch ’em to the post, and jest set in the back door and milk ’em.”

“Under water?” sez I; “milk under water?”

I see he wuz gittin’ sick of the idee—sick as a dog, but he sez—

“Yes, milk ’em under the water in rubber bags, jest as Ezekiel did, and Malachi, and all the rest on ’em.”

“Wall,” sez I, “you’ll keep bachelder’s hall then, and cook your own vittles and make your own butter for all of me. I hain’t a-goin’ into any sech enterprise.”

“Wall,” sez he, “that don’t surprise me at all; I never yet got up a uneek idee but what you backened it all you could.”

Wall, we hung round here for some time, and I meditated on how the prisoners must have felt, condemned to

“Fetters and the damp vault’s dayless gloom.”

And as I see how they had wore the very stuns away, a-pacin’ back and forth in their narrer bounds like caged lions, I felt like sayin’ with Byron:

“May none these marks efface,

For they appeal from tyranny to God.”

And it wuz with quite saddened emotions that we wended our way back to the tarvern Byron.

I see Al Faizi wuz dretful mournful-lookin’. It always affected that good creeter to see how Truth and Liberty and Jestice have always been trompled on by Error and Ignorance all through the ages and in all countries, and always would, so fur as I could tell.

Geneva! Chamouni, how they glide past the roused eye of my mind, that don’t need spectacles—no, indeed! For never on earth, it seems to me, was there sech grandeur of seenery as wuz here in Chamouni. And the hull world seemed to have found it out, for folks from all the countries of the earth seemed to be repr