CHAPTER XXX.

MILAN, GENOA, VENICE.

Wall, at last, under the fosterin’ care of Martin, we wuz conveyed along into Italy and put up to a place called Milan. But one memory of our way thither stands out as plain in my mind as our centre-table duz in my parlor; it is of beautiful Lake Maggiore. A more beautiful piece of water I don’t believe moistens this old earth. Them sweet blue waters, with lovely Isola Bella terraced into hite after hite of verdure and beauty, and other islands a-standin’ out like clear blue stars in a clear blue sky, and the Italians in their picteresque dress, priests, peasants, etc., etc., wuz a seen of enchantment, and even Martin looked kindly on it, and admitted that it looked well. “But,” sez he—

“What is it compared to our own Thousand Islands? Why, nothing at all. Our own St. Lawrence would take in the whole of Lake Maggiore at one mouthful, and not know the difference.”

Sez I, “Martin, don’t run down the beauty of another country a-praisin’ up your own.”

“Well,” sez he, “do you find such perfection here as in our own country?”

Sez I reminescently, “I find better telegraph poles.” Sez I, “Think of the clear granite shafts, good enough for monuments, and then think of the humbly, crooked wooden poles that disfigger our American landscape.”

“Well,” sez he, “you don’t often find them here.”

Josiah sed if I wuz so bent on havin’ stun telegraph poles, he and Ury could build up one out of loose stuns in front of the house. Sez he, “We might make it sort of a monument shape, and Ury might kinder block out my figger on top.”

Sez I, “I guess it would be a work of art if Ury did it.”

“Wall,” sez he, “I might have a tin-type or sunthin’ fixed on, or a lock of my hair. It would be real uneek, and my fellow-townsmen would think the world on’t.”

Mebby he’ll forgit the idee, and mebby I’ll see trouble out on’t yet.

Wall, in Milan our first move wuz, of course, to see the cathedral. I’d seen so many picters on’t that it looked as familar as Betsey Bobbettses liniment, only fur grander and more impressive lookin’.

Yes, after lookin’ at that wonderful buildin’ on the outside and inside, I felt as if I wuz a heathen creeter who had never seen a cathedral or a meetin’-house in my life. Why, to make it clear to everybody jest how grand and extensive it is, I will say that if the pine woods on the hill back of Deacon Henzy’s wuz all turned into pinnakles and monuments and arches, and every pine needle on ’em wuz ornaments of delicate tracery and carvin’ and beautiful design, it could not be more impressive, and to anybody who has seen them woods that is sufficient. It is a dream to remember in still nights when you lay on your piller and can’t sleep. I think on’t time and time agin. Why, it is so big that you could carry on a Stock Exchange meetin’ at one end and a funeral at the other, and not interfere with each other in the least; you couldn’t hear the bulls and bears yellin’ or the mourners a-weepin’ and wailin’, not at all.

And you climb up five hundred steps to the top, and look down on all the beauty and glory of the world—it is a sight, a sight.

Wall, Martin sed that he must make all haste possible a-travellin’ through Italy, as business wuz a-callin’ him home, but he must go to Genoa, the birthplace of Columbus. Sez he, “Of course, considering what he discovered and where he was of late celebrated, that is by far the most important place in Europe.”

Wall, I wuz glad enough to visit the birthplace of that good, misused creeter. So we anon found ourselves in Genoa, the Superb, as some call it, and in good rooms in a big, comfortable tarvern.

The first thing we went to visit wuz the statute of Columbus. It towers up, a poem in white marble; and in a settin’ poster, on the four sides on’t, are Religion, Gography, Strength, and Wisdom, and all round ’em and between ’em are carved the leadin’ events of Columbuses life. Every one of them symbols carved out there—Religion, Strength, etc.—Christopher had, and the world realizes it at last.

I should think the world would have been ashamed of itself after picterin’ out his grand doin’s, his discoveries in the New World, to have sculped him out in chains; it wuz a burnin’ shame, but his memory is a-walkin’ down through the ages now free and soarin’, no chains on it—no, indeed!

But, poor creeter! how he would have enjoyed bein’ made sunthin’ on, and used well while he wuz here in the body! How he would have enjoyed havin’ enough to eat, and hull clothes!

But sech is life.

Wall, Martin renewed his strength a-lookin’ on Columbuses statute and a-realizin’ what it wuz he discovered and how his discovery is a-branchin’ out and spreadin’ itself. He felt well.

Right acrost from the statute stands a big house, which has writ on it, “Christopher Columbus Discovered America.” Martin didn’t need to be told on’t—no, indeed!

As nigh as we could make out, Columbus wuz born in that house. They showed us the very room where he wuz born; but my lofty emotions in viewin’ the spot wuz quelled down with the thought that he wuz born in seven or eight other places. Poor creeter! what a time he did have from first to last!

In the Municipal Palace, among other curous and valuable relicks, we see lots of relicks of Columbus—amongst ’em some autograph letters that he had his own hand on.

Josiah sez, “He’s some like you, Samantha—ducks’ tracks is plain readin’ compared to ’em.”

I looked coldly at him, but did not dane to argy.

In a glass case, amongst lots of other things, we see the violin of Paganini, the greatest violinist that ever lived.

He, too, wuz a discoverer; divine realms of melody wuz brung to view by his heavenly vision. He wafted his hearers into that realm on the flood of melody. I took sights of comfort a-lookin’ at that old fiddle.

DIVINE REALMS OF MELODY WUZ BRUNG TO VIEW BY HIS HEAVENLY VISION.

When my thoughts git started back to Italy, as thoughts will, no matter where your body is—a-settin’ in the meetin’-house or out to the barn or anywhere—they always linger sort o’ lovin’ly on Venice—Venice that stands out in my mind all by itself amongst cities, jest as prominent as Thomas J. duz amongst boys.

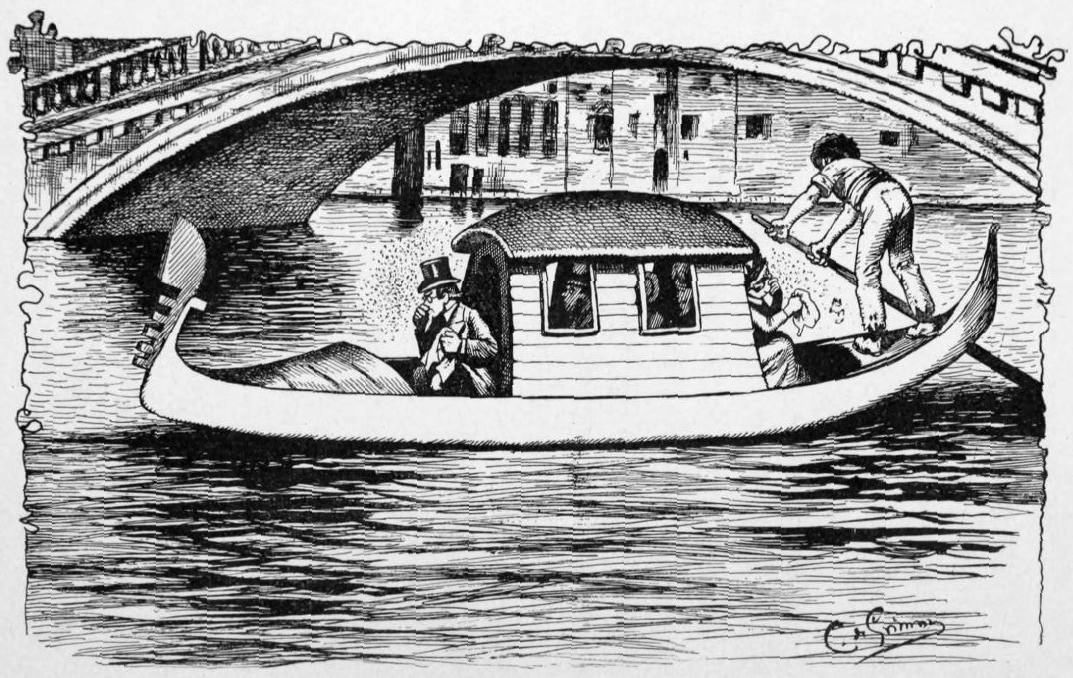

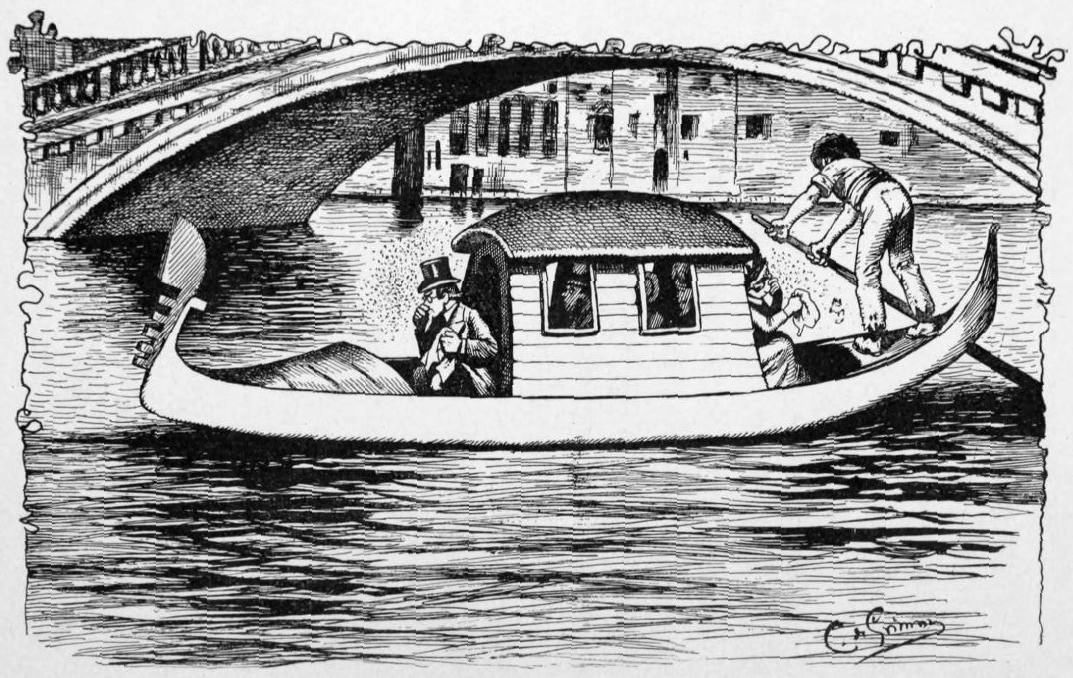

My Josiah wuz dumbfoundered when we emerged from the depot to think that he had got to go to our tarvern in a boat; but so it wuz.

Then he demurred agin about the convenience we wuz a-goin’ in.

He sez, “Dum it all, I hain’t a-goin’ to be drawed by a hearse whilst I am alive!”

But I soothed him down by pintin’ out that the boats wuz all painted black.

But wuzn’t it a curous sensation to drive along on streets of water, instead of good, honest dirt. Bein’ kinder skairy of water, I whispered to Josiah—

“As bad as our roads in Jonesville be durin’ the worst of Spring mud, I’d ruther navigate ’em with our wheels up to the hubs in mud than to ride down these water streets.”

Sez he, “Samantha, we didn’t realize our priveliges then, we made light on ’em.”

“Yes,” sez I, “you used language on them roads that you wouldn’t use now if you wuz set back on em.”

“I didn’t talk any worse than the rest of the Jonesvillians!” he snapped out. “And how these streets smell—dead cats and pollywogs!” sez he, turnin’ up his nose real high.

“Wall,” sez I, “less count over our blessin’s. We can hold our noses while we are a-countin’,” sez I. “Look at them towerin’ marble palaces; see the carvin’ on them tall pinnakles and the arched winders and the fretted ruffs,” sez I.

“The ruffs don’t fret no worse than my mind duz!” sez he. “Oh,” he whispered with a low groan, “shall we ever see the cliffs of Jonesville once more!”

“Don’t give up, Josiah,” sez I, “here right in the dream of the world, Venice, the beautiful.”

Sez Josiah, “I hearn there wuz a sayin’, ‘See Venice and die,’ and I can tell ’em that if this smell keeps on, and if the dum muskeeters keeps on a-bitin’, there’s one man who will foller their advice.”

“IF THIS SMELL KEEPS ON, AND THE DUM MUSKEETERS KEEPS ON A-BITIN’, ONE MAN WILL ‘SEE VENICE AND DIE.’”

Sez I, “They hain’t muskeeters, they’re nats, and it wuz Naples that wuz said on; and,” sez I, wantin’ to roust him up, “they say Venice is perfectly beautiful by moonlight.”

That kinder nerved him up, bad as he felt—he seemed to look forrered to it, and after a good meal and a good rest, when we did set off by moonlight, hirin’ a gondola jest as we would a express wagon to home, he admitted the beauty of the seen.

And it wuz like a journey through fairyland. The long, glassy streets, all lit up by lights from the tall, white palaces on each side on us, and by the lanterns of the passin’ gondoliers; the soft, sweet voices of the gondoliers as they called out to each other in their melogious Southern tongue; the glidin’ boats movin’ past us like shadder craft, with the handsome, graceful forms of the gondoliers a-drivin’ ’em, and anon or oftener the sweet strains of a guitar, and some divine voice in song; and the admirin’ surprise when you’d turn a corner and look down another street of beauty, differin’ in form of glory.

Oh, it wuz a seen to be remembered as long as Memory sets up on her high-chair under my foretop! And what hantin’ thoughts kep’ company with me and filled the gondola to overflowin’! I seemed to see Titian with his artist’s eyes and inspired pencil—the old Doges with their embroidered and jewelled robes—sad-eyed Beatrice Cenci, Antonio, Shylock, Wise-eyed Portia—I seemed to hear her sayin’,

“The quality of mercy is not strained,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from Heaven.…

It blesseth him that gives, and him that takes.”

The gondola wuz crowded by the fantom crowds that set round me onheeded by my Josiah, jest as sperit crowds may be cramped all round onbeknown to us.

Wall, I expected that about the most interestin’ thing in Venice to me would be the Bridge of Sighs, that stands, as Byron so eloquently observes, with a palace on the nigh side, and a prison on the off side (I may not have got the exact words, but it is the same meanin’). And I had more emotions there than I could count, as I looked at it.

Al Faizi wuz dretful interested in the old prison and dungeons and in the relicks of the infamous Council of Ten.

He writ pages in that book of hisen, and didn’t come no more nigh depicterin’ all their atrocities and abominations than one drop of water would to exhaustin’ the ocean.

In the palaces we see the height of luxury and richness of beauty. In the prisons and dungeons we can see the black depths of terror and cruelty of the time when the Council of Ten ruled Venice.

The Doge’s palace is a dream of magnificence. You look up the Giant’s Staircase, way up—up to the great statutes of Mars and Neptune, where them mean creeters wuz crowned—the Doges, I mean. And then you can’t help meditatin’ that whilst they clumb to the very top of magnificence, they didn’t do well, they didn’t die peaceable in their beds, none on ’em.

No, they wuz pizened, or had their heads cut off, or sunthin’ or other, that interfered with their comfort.

I wouldn’t want Josiah to be a Doge—not if he could be jest as well as not. No, Dogein’ seemed to be resky business in them days, and I presoom that it would be now.

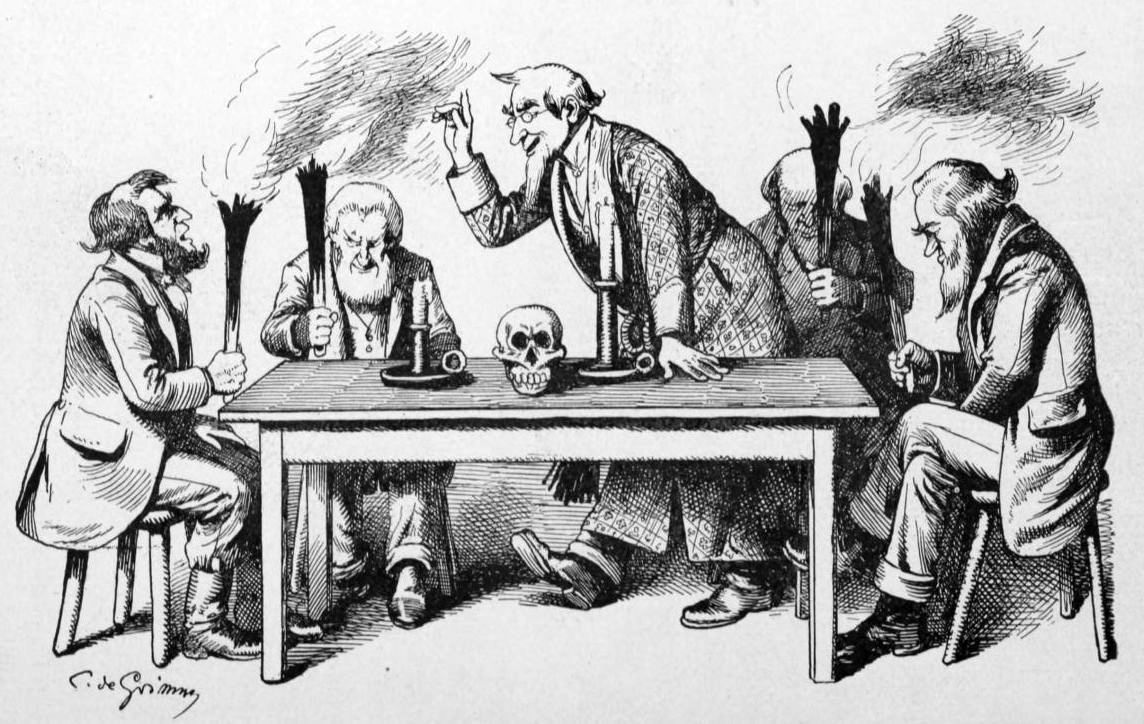

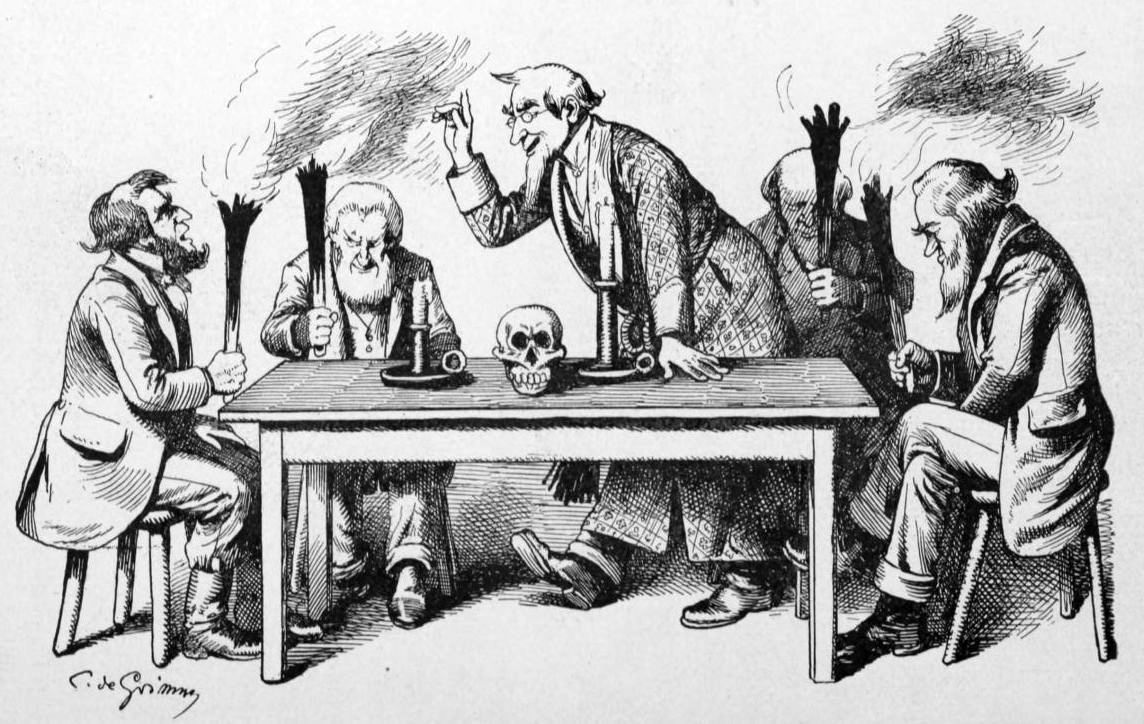

And then they wuz so awful mean some on ’em—jest read what they done, it’s enough to skair you to death almost. I had dretful emotions as I looked at that long table where the Ten ust to set in silence, and condemn men and wimmen to death.

They ort to be ashamed of themselves.

And then the Lion’s Mouth, where the papers accusin’ folks wuz dropped by the people. The paper dropped down into a chest so’s the wicked old Ten could git holt of ’em.

Miserable creeters! I’d love to gin ’em a piece of my mind.

But Josiah wuz all took up with the idee; sez he—

“How convenient, how charmin’ it would be to have a complainin’ box rigged up in the barn over the manger or by the side of the haymow, so when I wanted to complain of Ury I wouldn’t have to jaw him and have him sass back! How much easier it would be than jawin’! He’d like it better, too. And you can have one, Samantha, to complain of Philury; you could jest drop ’em in, and then you wouldn’t have to tell ’em over to me when she wuz wasteful or slack, or acted. Jest put ’em down on paper, drop ’em into the box, and nobody but Philury would be the wiser.”

Sez I, “Do you spoze I’m a-goin’ to be feelin’ round writin’ complaints while a batch of cookies are bein’ spilte, or a lot of good vittles throwed to the hens? No, indeed! My tongue is good yet, and active.”

“Yes, indeed, it is!” sez he with a deep groan (I d’no what he meant by it).

“But,” sez he, “it would be good for it to rest a spell, and it would be a good thing for me, anyway, specially nights when I wuz sleepy,” and agin he sighed (he acted like a fool).

“And if you say so,” sez he, “we could have one rigged up together for both on us—we ort to be able to complain of our hired man and woman in one complainin’ box. We might have it over our back door, or on the smoke-house.”

But I waived off his idee, and mebby he gin it up, and mebby, agin, he’ll try to rig up some contrivance that won’t do no good, and take time and money.

Another one of the queer things them old Doges ust to do wuz to marry the Adriatic to the city at a certain time every year.

What did they want to marry water for?

But Josiah wuz all worked up with the idee, when he hearn us a-talkin’ about it, and about the magnificent ceremonies they went through with at the weddin’.

Sez he, “How uneek it would be for me to marry the creek to Jonesville and perform the ceremony out to our mill-dam! It would be beautiful, and it would be as cheap as dirt, too; Ury could fix up a raft, and I could take one of the curtain rings out of the spare bedroom to wed it with.”

“What do you want to be weddin’ the creek for?” sez I coldly.

“Oh, for fashion,” sez he—“style. Old-fashioned things are so stylish now,” sez he. “You know how them old, long, black clocks, humbly things in the first on’t as they could be—you know how they’re set up in the boodores of luxury now, a-lookin’ like a coffin on end. And spinnin’-wheels and sech that our grandmas ust to hustle out of the room, if company come, now they’re sot up on velvet carpets, and made sights on. And this manoover would be dretful stylish. Oh, how the Jonesville bridge would be crowded! how the Jonesvillians would look on in admiration to see the sight!

“Of course I should wear my dressin’-gown. The public has never had a chance to see it on me yet, you have always been so sot on keepin’ me to home in it. This would be a very agreeable treat to have on Fourth of Julys, or any national holiday, and I could carry it out perfectly and dog cheap, with a little of Ury’s help.”

But I sot my foot right down on the idee to once. Sez I, “It looks silly as anything in them wicked old Doges, and you hain’t a-goin’ to import any of their tricks into Jonesville. Next thing I’d know you’d have a inquisition a-goin’ on, and a secret tribunal of Ten.”

“NEXT THING I’D KNOW YOU’D HAVE A INQUISITION A-GOIN’ ON.”

“I’d like it first-rate,” sez he, “if I could be the 10. I’d like to shake some of the sins and foolishness out of Brother Gowdey and Deacon Henzy,” sez he, “and bring ’em into my way of thinkin’.”

“There it is!” sez I. “Intolerance, bigotry, persecution, how fresh they be to-day in the human heart! Jest as ready to spring up and act in 1895 as a thousand years ago.”

“Wall, I hain’t said I wuz a-goin’ to start it up agin,” sez he, kinder cross like; “I only spoke on’t.”

I expected trials when I sot out to take my pardner through Europe, and I wuzn’t dissapinted in it. But if it hadn’t been for his ambition for display, and his bein’ carried away by novelties, and his appetite, he would have acted real well. But, anyway, act or not, he’s the one man in the world for me, and visey versey.

But, as I wuz a-sayin’, the palaces of them old Doges rousted lots of emotions in my brain, and the fantoms of their victims seemed to hover round them old palaces as thick as the pigeons that come with a rush of wing down into the great square of St. Mark at jest two o’clock, where they are fed by order of the government.

The grand old Church of St. Mark interested me dretfully. It is built in the form of a Greek cross, with a big dome in the centre, and full, full to overflowin’ with glory of mosaic, precious stuns, picters, monuments, altars, pillars, colenades, gold, silver, and splendor of all sorts.

Josiah sez to me, “Our Jonesville meetin’-house wouldn’t show off much compared to this.”

But I wuz some consoled in this by thinkin’ that if our meetin’-house wuzn’t so gorgeous, there wuz jest as big a lack of beggars and poor people of all kinds a-hoverin’ on the outside on’t, and sez I—

“If they should sell off some of their costly things and try to improve the condition of these poor beggars, they would raise themselves as much as twenty-five cents in my estimation, and I d’no but more.”

And Josiah sez, “It is hard to make a rotten string stand up straight—it is hard to brace up laziness, and dissipation, and improvidence, and make anything on’t.”

I couldn’t dispute him, nor didn’t try to. But I did love to prowl round in those old meetin’-housen and see the wealth of interestin’ things in ’em.

In the Church of Santa Maria d’Frari, the beautiful monument to Titian took my admirin’ interest. It has angels, lions, all sorts of sculptered figgers in elegant carvin’, and beautiful bas-reliefs of his greatest works—“The Assumption,” “Martyrdom of St. Lawrence,” and “Peter Martyr.”

Then the monument to Canova is a sight to see in its beauty. Wall, he ort to had it; he did enough work to make the world more beautiful.

In the Academy of Fine Arts we see sech sights of beautiful picters that my brain almost reels now, a-tryin’ to recall ’em. But Titian’s “Assumption of the Virgin” is one that you can’t forgit, no matter how clost other idees press around it and squooze aginst it.

Great picters by Paul Veronese, Tintoretto, and other great masters—the walls are jest seens of beauty.

I wouldn’t want it told on—it ort to be kep’, but Josiah told me right there in that sacred spot, that he wuz sick of Madonnas—sick as a snipe.

But I told him that I wouldn’t own up to it, if I wuz.

And he said he didn’t care who hearn him.

I wuz kinder sick on ’em myself, but didn’t want to own up to it right there in a meetin’-house. But, truly, anybody will see enough Holy Families, Virgins, Madonnas, etc., to last ’em a long life, unless they’re extravagantly fond of ’em. And every artist seems to have painted his own idees of the Holy Mother—mebby from his own sweetheart; anyway, no two of ’em are alike. Most of ’em are real fat and healthy lookin’. I never spozed she enjoyed sech good health as they depicter; I thought she wuz more kinder spindlin’ lookin’. And then I imagined there wuz a ineffible look to the face of the Mother of our Lord, sech, as it seems to me, they hain’t none of ’em ketched. The Mother of our Lord! What a face she ort to have to fit my idees of her! It’s resky work, paintin’ divine things. I wouldn’t want to undertake it, or have Josiah. Now I see the picter of the Deity once painted with a hat on.

I didn’t love to see it.

Why, even to Moses the Great Presence wuz surrounded by a flame of fire; and St. Paul fell to the ground, struck by the blindin’ glory on’t, and he wuz never able to put in mortal words the sights he see—“Whether in the body or out of the body, God knoweth.”

He wuz reverent. And it don’t seem quite the thing to try to paint ineffible glories with chrome yeller and madder. Howsumever, I spoze they meant well.

And, indeed, some of the picters we see as we journeyed through the Italian cities are all placed in rows around the inside of my brain, and can’t never be moved from there—no, the strings must break down first that they hang up on.

In Florence the Beautiful, oh, the acres and acres and acres of beauty that I walked through, full to overflowin’ with beauty and glorious conceptions and the white splendor of marble poems! The works of Michael Angelo I hain’t a-goin’ to forgit them—no, indeed! nor Lorenzo Ghiberti, nor the picters by Titian, Raphael, Rembrandt, Tintoretto, Veronese, Van Dyke, Rubens, etc., etc., etc., and so forth, and so forth, and so on, and so on.

I walked through the long picter galleries with my brain and heart all rousted up, and enjoyin’ themselves the best that ever wuz, and my legs all wore out and achin’ bad. And Josiah groanin’ audibly by my side. And Martin patronizin’ the marvels of ancient and modern art, and havin’ a good time. Al Faizi with his hat off, reverent and devout in the presence of so much divine beauty. And Alice, I spoze, thinkin’ of the past and the futer, and Adrian eatin’ candy, etc.

Time fails to tell what we see. It seems to me it would be easier to tell what we didn’t see; I guess it wouldn’t take so long, but I will desist.

But a few memories stand out shinin’ amidst the bewilderin’ maze. One of ’em is standin’ in the cell of Savonarola, that noble creeter, raised up to the pinnakle of saintship by the fickle populace, who knelt and worshipped him, and then so soon crucified him. And he all the time a-keepin’ on stiddy, jest as good and noble and riz up as he could be. Yes, his last words to his persecutors gin a good idee on him—

“You can turn me out of earthly meeting-houses, but you can’t keep me out of the Heavenly one.”

I may not have used the same words he did, but it wuz to that effect. I had a sight of emotions as I stood in that narrer place that once confined the form of that kingly creeter.

And then the tomb of Galileo. I always liked him the best that ever wuz. He wuz also persecuted for knowin’ things that them round him didn’t know, and thinkin’ thoughts and seein’ sights that they didn’t. And in order to git along with ’em round him, he had to promise to stop teachin’ the truth. The Majority had to be appeased by the old Ignorance. It has to now, time and agin. But he kep’ on a-sayin’ to himself, and out loud, when he got a chance to—“The world duz move.” Men and wimmen to-day, who feel some as Galileo about men’s and wimmen’s rights—licenses, the higher spiritual knowledge—they keep on a-sayin’ all the time, every time that they can git a chance to edge a word in between Ignorance and Bigotry and shaky-kneed Custom, who stand all shackled together with mouldy old chains of prejudice, every time they can git a openin’ between these tattlin’, but hard-lived old creeters, they keep on a-sayin’—“The world duz move.”

Folks will fall in with ’em after a time, jest as they fell in with the idees of Galileo; now they persecute ’em.

But more interestin’ to me than the glories and marvels of the Medician Chapel, the Pitti and Uffizi galleries, the Boboli Gardens, the monument to Dante (smart creeter he wuz, and went through a sight from first to last; he and she both—Beatrice, I mean)—

But of fur more interest to me it wuz to stand in the house where the slender little English woman dwelt while her soul was slightly imprisoned in her frail body, while she held “The poet’s star-tuned harp to sweep.” And where at last “God struck a silence through it all, and gave to His beloved sleep.”

“Sleep, sweet belovéd, we sometimes say,

Yet have no tune to charm away

Sad dreams that through the eyelids creep;

But never doleful dream again

Shall break their happy slumber when

He giveth His belovéd sleep.”

Yes, she sleeps well now. All the melancholy and charm of Italy, all its magnificence, all of its splendor, its ruins—all seem to be centred in that one little room. I had emotions there that it hain’t no use dwellin’ on.

Figgers seemed to start up and bagon to me from every side. Aurora Leigh, with her sad, sweet smile, stood in front of me with that lover of hern; the Portuguese lovers, with hearts of fire and dew too; the “Poet Mother” holdin’ her two boys to her heart, knit to that heart by ties of iron; Nino and Guido, little babies, teaching ’em to—“Say first the word country,” after that mother and love. Then I see her alone in the house—alone.

“God, how the house feels!”

While Guido and Nino lay dead, shot down by the balls of the enemy—“One by the East Sea and by the West”—then she remembered that she had learnt ’em to say first the word “country,” puttin’ it before “mother and home.”

She wuz kinder sorry she’d done it at first, I guess. She forgot Glory and Patriotism, for this woman—this “Who was agonized here, the East Sea and West Sea rhymed on in her head, forever instead.”

She couldn’t think of anything else, only the mightiness of human love and grief.

I don’t blame her; I should felt jest so myself if it had been Thomas Jefferson shot down. What would the glory of Jonesville be to me, if his bright, understandin’, affectionate eyes wuz closed in death? I, too, should think that everything else wuz “imbecile, hewin’ out roads to a wall.”

How black that wall would look to me!

And then the cry of the Human, how it rung in my ears—

“Be pitiful, O God!”

Yes, indeed, in how many crysises have I felt the hite and the depth of that cry!

I had powerful emotions, powerful, and sights of ’em—so did Al Faizi. He jest doted on Mrs. Browning’s poetry, and he sot a good deal of store by the poetry of her relict—her widderer. And Robert duz write first-rate, but pretty deep, some on ’em. I’ve grown real riz up and breathless a-hearin’ Thomas J. read about “How they brought the good news from Ghent to Aix.” And I love to hear Thomas J. read about the “Lost Leader,” and beautiful “Evelyn Hope,” and etc., etc. But, on the hull, I sot more store by the poems of his wife.

But, as I say, I always respected and admired Elizabeth’s widderer. He insisted on marryin’ the woman he loved, no matter how poor health she enjoyed. I presoom his folks objected and thought that Robert would do better to marry a woman that wuz enjoyin’ better health. But he never thought of doctors’ bills or poultices—things that fill up littler minds—no, indeed! nor she didn’t either. They felt only the supreme joy of congenial minds and hearts, and love that lifts the soul up to the divinest hites mortals can ever stand up on.

She says, and it seems almost like liftin’ a veil before the Holy of Holys, and as if I ortn’t to speak of it, but I will venter—

She sez:

“First time he kissed me, he but kissed

This hand wherewith I write,

And ever since it grew more fair and white,

Slow to world greetings, quick with its Oh, list!

When the angels speak.”

How the words fell from her innocent soul, and how they must always reach the same place in ’