CHAPTER XXXVIII.

HOME AGAIN, FROM A FOREIGN SHORE.

Jonesville wuz bathed in the rosy hue of sunset when Ury let down the bars and we passed up into the lane leadin’ to our dear home—that sweet, restful haven, into which Josiah and me truthfully felt that our barks would sail in and be moored forever and ever.

Yes, we both felt that nothin’, nothin’ could tempt us agin to spread our sails and float out of that blessed Home Harbor.

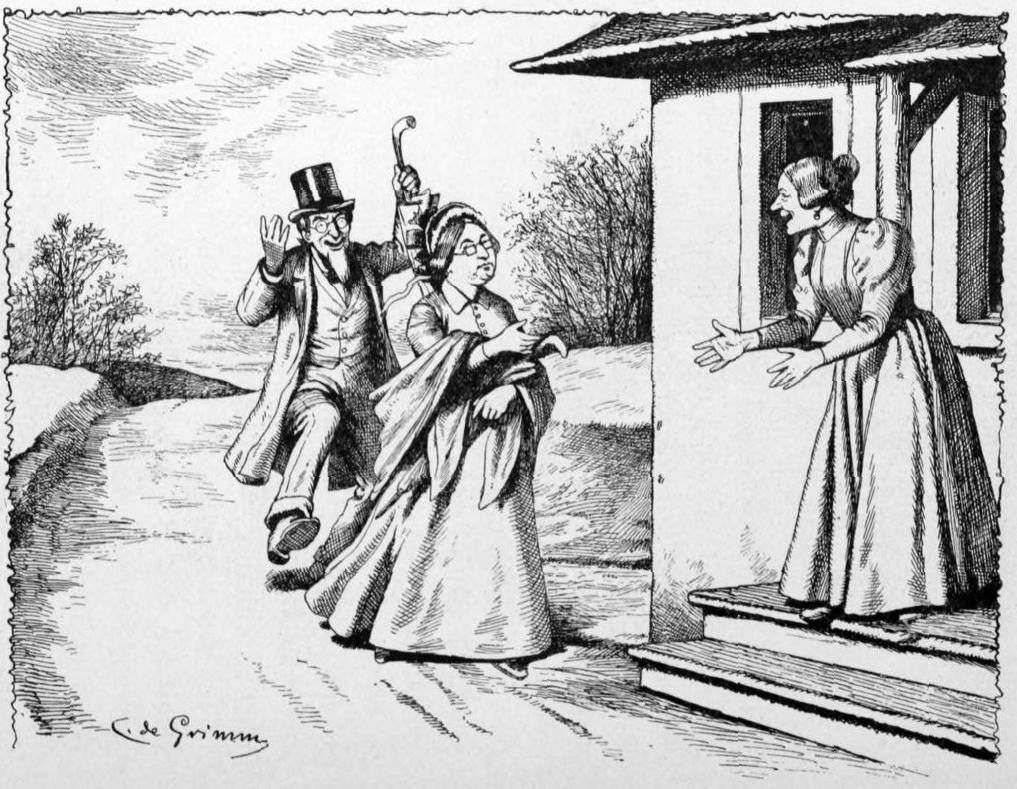

How soft the light fell onto the white curtains with lace agin’! How sweet the rosy glow illumined the piaza and front yard, and how it played round the red chimblys and Philury’s collar, as she stood in the front stoop to welcome us home! Inside the house wuz all lit up, and when we entered, there wuz the children all come to surprise us, and welcome us home. They had sent Philury out, like the dove, on the front doorstep, while they stayed in the ark to surprise Ma and Pa when we come.

THEY HAD SENT PHILURY OUT, LIKE A DOVE, ON THE FRONT DOORSTEP TO MEET US.

Oh, how glad they wuz to see us, and visey versey. Yes, indeed, I guess it wuz visey versey—the children and grandchildren almost eat us up, and we them.

A beautiful supper wuz a-waitin’ the tired-out travellers. The girls had laid to and helped, and it wuz a supper long to be remembered, and the children’s and the grandchildren’s demeanors to us wuz as tender as the briled chicken and cream biscuit, and the ties of love that united us all together wuz as strong as the coffee, and stronger, too, and mellered down by our happiness, jest as that wuz with lump-sugar and rich cream. And, oh, how good! how good it did feel to be to home! Josiah the first thing pulled off his boots and went round in his stockin’ feet.

I sez, “Why do you do that, Josiah?”

“Oh, for no reason, only to swing out and do jest as I’m a-mind to. After bein’ cramped and hampered for months, I’m a-goin’ to act and feel to home, and I’m a-goin’ barefoot for a spell,” sez he, “as soon as the children go.”

And, sure enough, he did, for all I could do and say, and he sung several pieces while I wuz ondressin’—he sung ’em loud. I remember he sung the hull of “Robert Kidd” and “André’s Lament,” besides some hymns.

Sez he, “I’ve been pent up and bound down so long that I’m a-goin’ to swing right out and act all I want to.”

And happy—why, happy is no name for the feelin’s of that man, and I felt the same—yes, indeed! Only, as my nater is, I acted more megum, though I did kinder jine in with him in the chorus—

“My name is Robert Kidd,

As I sailed, as I sailed.”

I wuz so perfectly happy that I had to.

And when he struck into the hymns I jined in strong, right there in my nightgown—“On Canaan’s happy banks I stand,” and “Long time I have wandered,” and etcetery.

Why, Josiah sung the most of the time for days and days.

When Deacon Henzy come to see him, instead of advancin’ and shakin’ hands dignified, as a foreign traveller ort to, he jest advanced onto him, a-singin’ loud—

“Home agin, Deacon, home agin, from a foreign shore.

And, oh! it fills my soul with joy

To greet Deacon Henzy and the rest of the Jonesvillians once more.”

It spilte the meter, but he didn’t care. He acted fairly crazed with joy to be home.

The first thing he done the next mornin’ when he got up wuz to throw his best clothes in a sort of a scornful heap behind his closet door. He throwed ’em some as if he hated the very sight on ’em. When I found ’em afterwards, all tumbled in together, we had a number of words.

But, as I say, he throwed his best clothes there, and specially his stiff collars and cuffs—them looked some as if they’d been trompled on.

And then that man got on the worst-lookin’ pair of pantaloons and vest you ever see—holes in the knees, and the vest ripped up in the back, and the pockets hangin’ outside. I’d been a-savin’ ’em for carpet rags.

And he went down suller and took a old coat offen the apple-ben. We had used it for two winters to cover up the apples in extra cold nights. And the land knows where he got the hat he put on—a old straw, the rim a-hangin’ half off, and the crown all jammed in. I guess he found it up in the woodhouse chamber.

But, anyway, his looks wuz sech, so onbecomin’ to a deacon and a pathmaster, let alone a cultered gentleman of foreign travel, that I took him to do sharply about it.

HIS LOOKS WUZ SO ONBECOMIN’ TO A DEACON AND A PATHMASTER.

Sez I, “I won’t have you a-goin’ round lookin’ worse than any old scarecrow, Josiah Allen.”

He took up a position in front of me, where his rags showed off to the most plainest advantage, and sez he—

“As you see me now, Samantha, you will see me henceforth. I shall never, never be dressed up agin as long as I retain my conscientiousness.”

He spoke so firm, I felt some browbeat and skairt.

Sez I faintly, “Do you expect to go through your life a-lookin’ as you do now?”

“Always, always, Samantha; only worse, if I can manage it.” Sez he bitterly, “I am a man that has been dressed up too long; the iron has entered too deep into my soul—the worm has turned,” sez he. “I calculate to go in rags the rest of my life. And I wish,” sez he in a pleadin’ axent, “I wish that you would promise that you would bury me in this suit—that you would take a vow that I shall not be dressed up.”

I wuz at my wits’ end; he looked as determined as any old hen turkey ever did on her nest.

But by a happy inspiration I sez—

“Wouldn’t you ruther lay in your dressin’-gown, Josiah? Think of them beautiful tossels,” sez I.

I see a change come over his mean; he wavered and turned onto his heel, and went out-doors.

And I may as well tell the end on’t. It wuz that dressin’-gown that gradual won him back into decenter clothin’.

I lured him into that at first, and then gradual into pepper-and-salt, and so on to broadcloth; but it wuz a hard tussle! Collars and cuffs wuz my worst battle-field, but I got the victory over ’em at last.

Oh, dear me, dear me, suz! what hard times female pardners do have anon or oftener; but yet I believe that pardners pay, after all.

And it did seem so good to walk round the house, free and ontrammelled, and see the old bureaus and tables once more, and sasspans and things; and go out into the garden and see the garden-truck, and walk out to the barn and gather the eggs, and count the chickens.

And plunge into all the sweet delights that make home a perfect Eden.

Yes, we both felt that we should never want to move a inch from our own fireside. But how little—how little we can tell what is ahead on us in the onseen futer.

In this case Alice wuz ahead.

We hadn’t been to home more’n several weeks when that sweet creeter wrote to me, urgin’ me hard to come and see her.

She didn’t make no open complaints, but all through the letter I could read between the lines, as it wuz, the echoes of a sad heart.

I felt, as I read it, that I ort to go right away and see her.

But I hated to leave home agin—I hated to like a dog.

So I writ her back as lovin’ a letter as I could, and I kinder waved off the subject of my comin’, sayin’ I’d come jest as soon as I could.

A week or more passed, then come a letter from Martin, sayin’ Alice wuzn’t very well, and had sot her heart on seein’ me—wouldn’t I come?

I went.

Alice wuz dretful glad to see me, and in my lovin’ sympathy her white face seemed to git a little more color and brightness into it.

Good land! I see what ailed her jest as well as though I had took our big parlor lamp and walked through her mind.

Her father wuz jest as determined as ever that she should have nothin’ to do or say to Richard Noble.

And bein’ right here by his side, as it were, and forbid to see him or speak to him made it fur worse than it wuz when they wuz seperated by a ocean. Her Pa had planned in his own mind that this trip should ween her from him. But how mistook he wuz!

She had carried a faithful, lovin’ heart over the Atlantic, and had brung it back with her.

Distance had only drawed the ends of the love-knot, unitin’ their souls all the tighter. They couldn’t be ontwisted now by the hands of a Martin—no, indeed!

Martin wuz dretful good to me. He see that Alice loved me and brightened up considerable in my presence. And that would have made Miss Belzebub welcome.

And Adrian, how he did hang round me, sweet little creeter that he wuz!

Yes, Alice wuz the same, and Martin wuz the same as before his trip. He kep’ right on in the same old roteen of money-makin’, and money-savin’, and obstinacy, and sotness, and ambition, and etcetery.

I found that out only a few mornin’s after I got there.

I happened to take up a daily paper, and I read a piece in it about a horrible axident that had took place right there in the city a few days before—two children killed, and the driver of the car had died from the effects of the horrow and remorse he had experienced in causin’ the death of the two children.

Died! when the poor creeter wuz no more guilty than a babe for it. He wuzn’t no more guilty than the spokes in the wheels. They all wuz run by another’s orders.

As I sed, I wuz so horrified by it, that I felt that mad him or not, I must tackle Martin about the matter.

And I found that he wuz as stiffnecked and rambellous as a iron-clad about it.

And we had a number of words.

And in the course of our conversation I atted Martin agin about Alice’s lover. For her big, sad eyes had follered me all the time I’d been there, and I had vowed in my heart that I would help her to her happiness if I could.

As I sed, the pretty creeter had took her faithful heart over the Atlantic, and carried it round with her all the time she wuz there, and had brung it back with her.

Movin’ the body round don’t change the soul.