CHAPTER XXXIX.

MARTIN’S TERRIBLE LESSON.

Wall, I found that Martin wuz as immovable and sot as a rock. “As for Alice,” sez he, “I told you six months ago what I should do, and I never change my mind.”

And agin I sez, “Sometimes folks are made to change their minds when they don’t mean to or want to.”

But before I could multiply any more words with him a servant come in to say that a paintin’ had come that Martin had ordered while he wuz abroad. And he asked me quite polite to go in and see it.

He wuz glad of the interruption. He wanted to change the subject—he wanted to like a dog.

The picter had been onpacked, and wuz standin’ in the big hall, waitin’ for Martin to decide where to hang it.

It wuz called “The Mother’s Sacrifice,” and wuz the picter of a Eastern mother, who wuz a-throwin’ her child under the wheels of a juggernaut to insure its everlastin’ salvation.

Her face wuz torn with love and duty. It wuz a impressive picter. He gin twenty thousand dollars for it, for he told me so.

Sez Martin as we looked at it, full of the rich Oriental glow of forest and landscape, and the dark, frenzied beauty of the mother’s face and the innocent beauty of the child, who trusts to her love and care and don’t mistrust its impendin’ doom—

Sez Martin, “What a struggle is going on in that woman’s breast! how her heart is torn between her love for the child and her religious belief! What a masterly handling of the subject!” sez he.

“Yes,” sez I; “but what of the hearts of the mothers who see their children crushed down under jest as murderous wheels, and don’t have her religious zeal to hold ’em up? That Eastern mother thinks that this will insure her child’s eternal well-bein’—she thinks the wheels move on in the cause of eternal good. What would she think if she wuz a American mother, and knew these wheels murdered her child jest to save a little money—jest out of wicked, graspin’ avarice?”

Sez Martin coldly, “I don’t know what you mean.”

Sez I, “Yes you do, Martin; I mean your trolley cars, that move on and crush down childhood and age, when a little bit of money you spend for this ficticious woe would relieve the real agony which is goin’ on right before your front gate through your own neglect.”

I would gin him some sech little delicate hints, whether he liked it or lumped it, as the sayin’ is. Agin he sez in that dretful dignified way of hisen, “I don’t know what you mean,” and turned away.

But jest as I wuz withdrawin’ myself from the seen, for I felt that these little blind hits I gin him wuz enough for the present, Adrian come in, and Martin called out—

“Well, dear little Partner, what do you want?”

And Adrian sez, “Alice and I are going out driving, and I wanted to say good-bye to you.”

Martin kissed the pretty face, with his adorin’ love for the child a-showin’ plain in him. And then Adrian come and kissed me, his gold curls fallin’ back from his little, earnest face, and his black velvet cap a-settin’ ’em off first rate, and he sez to me, “Good-bye;” and I hadn’t any way of knowin’ that that good-bye would echo through the long futer and die out only at the Dark Portal.

Martin took out his purse and took out a roll of bills and handed ’em to Adrian, and sez he, “Hand that to your sister; I was going to give it to her last night—it is for a necklace she wanted. Be careful of it,” sez Martin as Adrian took it; “it is five thousand dollars, and that is worth taking care of, little partner.”

Wall, they sot off, and I went back into a little settin’-room acrost the hall from Martin’s study and took up a book and went to readin’.

It wuz a interestin’ book, and I wuz carried away—some distance away from the big city and trolley cars.

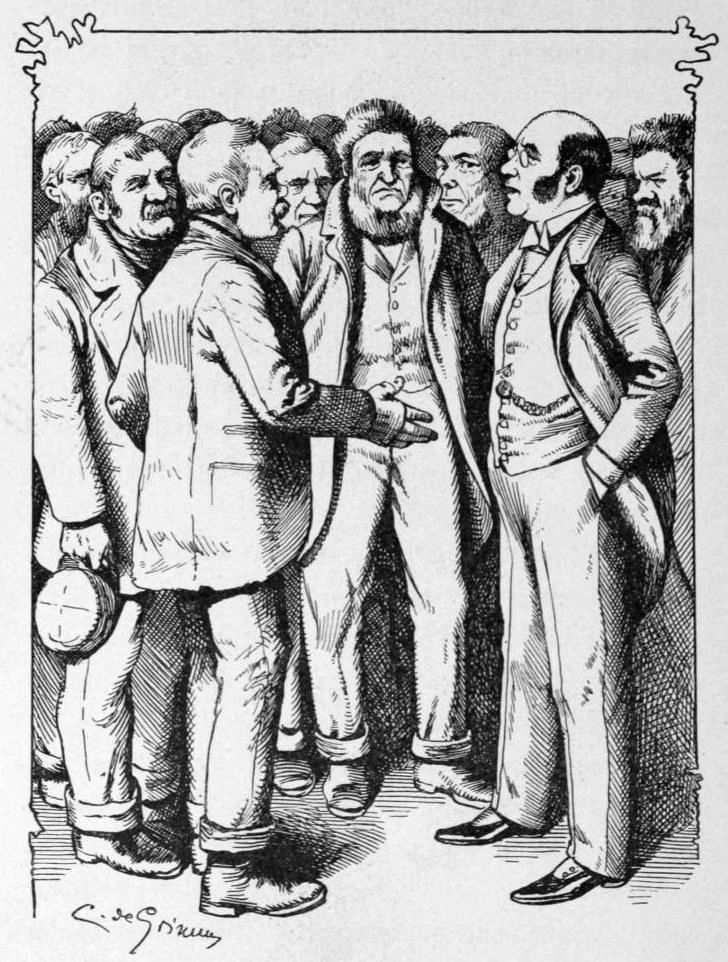

When I heard a hum of a good many voices in Martin’s room, and the door bein’ open, I couldn’t help hearin’ what they wuz a-sayin’. It seemed to be a deputation of some kind a-askin’ Martin for some favor or other.

For I heard him say out loud, “I am sick of these complaints.”

His tone wuz cold—cold as a iceberg. There wuz one man amongst ’em who seemed to be the speaker; he sez, “We are workingmen; we have homes and families. We work hard every day. We leave our children, that we may go away and earn food and clothing for them; our houses are the best that we can afford, but the best that we can pay for lay in the populous region where so many lives are lost by these cars. I know you are the owner of that line, and we have come to appeal to you.”

Sez Martin agin, “I am sick to death of these everlasting complaints.”

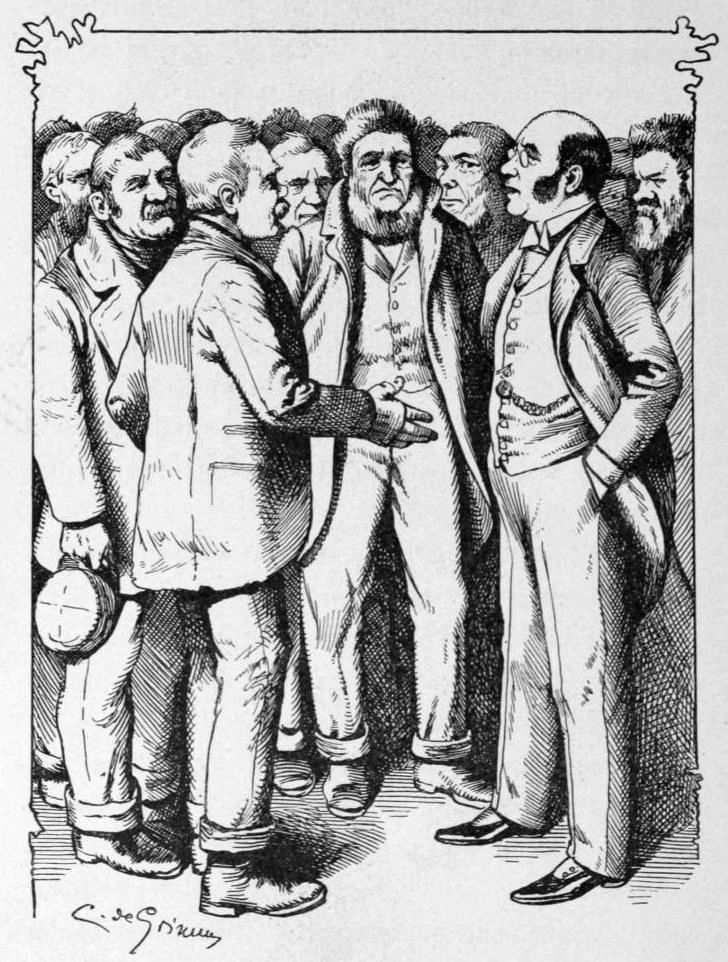

SEZ MARTIN AGIN, “I AM SICK TO DEATH OF THESE EVERLASTING COMPLAINTS.”

His tone wuz cold—cold as a frog, and I see from his voice that he wuz mad—mad as a wet hen.

The man that answered him I could see from where I sot wuz evidently jest a plain workin’-man, jest like ’em that you meet in droves at 7 o’clock in the mornin’ and six at night.

But I liked his looks—he looked rugged and honest, and his voice had a uncultured ring of common sense and honesty, and at times a deep sorrer and sense of wrong touched it to a rude eloquence.

Martin sez, and his tone wuz cold and smooth as a icesuckle in a January mornin’—

“What is it that you want me to do, anyway—tell me as briefly as you can, for my time is valuable.”

Sez the man agin, “We are workingmen and poor, and we do not expect to have many things that rich people have, but we do want our children to be educated. They must go out alone to their schools while their mothers are at home working to make a decent home for them, and they cannot follow them only with their thoughts and prayers.

“These cars going with the swiftness of lightning through these thronged streets, with no safeguard to protect them, are the means of making fathers’ and mothers’ hearts ache with fear and dread.

“One of my own children, a bright little lad, my only son, dear to me as my own life, was crushed down by them on his way to school.” The man’s voice broke here, for a rush of feeling swep’ up agin his voice, and stopped it.

“Another of these men lost a child, another saw an old mother crushed down before his eyes as she tried to cross the street, another—”

“There is no need of repeating all this to me. What do you want me to do?” I see by Martin’s voice that he wuz madder than that wet hen a-settin’, and obstinate.

“We want to have you give orders to go more slowly through crowded places and put fenders on the cars, so as to lessen the peril as much as may be, so we poor people, who have to live and labor in these dangerous places, can carry a lighter heart to our hard daily toil.”

“Leave me your address,” sez Martin sharp and cold, “and I will communicate with you.” Then sez he, “James, show these men to the door. Good-morning,” sez he. The door closed on the men, and Martin crossed the hall with a quick step, and come right into the room where I sot. In his haste to git out of their sight he had, as the sayin’ is, “jumped from the fryin’-pan into the fire.”

For I sez, and tears wuz in my eyes as I sed it—

“You will grant their request, Martin?”

“No, I will not grant their request;” and he went on sarcastically, “I don’t know what you people want. Do you want to do away with cars and railroads and go back to ox-teams and pillions? Here a few men take a big risk, put all their capital into an enterprise, doing the public an incalculable good, and then they have to be badgered night and day by the very ones they have benefited, and by a set of philanthropic fools.” I guess he meant me by that last term, but I didn’t care; I wouldn’t have cared if he’d called me a plain fool—I knew I wuzn’t. When you are out a-ketchin’ a tiger you don’t care for a muskeeter’s bite; no, your mind is sot on the tiger.

I sez, “The cost is but triflin’ to one of your means. Why not do it?”

“Because I am capable of attending to my own business, and I am not to be bossed by a lot of workingmen and wild-eyed reformers and sentimental idiots—I’ll do what I please.”

Sez I, “Mebby you will, Martin, and mebby you won’t.”

Jest as I said these words a cry come up from the streets—“A child run over! a lady killed! a child and a lady killed!”

“There,” sez Martin, actin’ impatient and mad as anything—“there is another text for you, Cousin Samantha; and probably the whole car full of people, who have rode all over the city for five cents, will all join in and shriek at me as a murderer and a villain, because a couple of fools have started to cross the track just in front of a car; in nine cases out of ten the fault is their own.”

But the cries outside grew louder and louder, and finally Martin went to the winder, kinder flingin’ himself along in a sort of a impatient way; and he had been nagged considerable—I had to admit it.

He went to the winder, which looked down onto the broad street below. He looked a minute; then shriekin’ out—

“My God! my God!”

He fell down jest like a log at my feet.

HE FELL DOWN JEST LIKE A LOG AT MY FEET.

And what wuz the sight that struck him down like a arrer?

Two men of the very deputation that had jest left the house wuz bearin’ between ’em the crushed form of a little boy—gold curls wuz hangin’ back from the velvet cap. A kind hand had covered the little disfiggered face with a handkerchief. Behind, two more of the men and a policeman wuz carryin’ the crushed, senseless form of Alice.

I hearn all about it afterwards. There wuz a florist jest acrost from Martin’s, where a little bend in the road made it impossible to stop. Little Adrian had jumped out of the carriage and run to choose a bokay of flowers to gin to me. They wuz the English voyalets he loved so well. One of ’em wuz in the buttonhole of the little velvet coat.

Dear little creetur!

And as he ran back the flowers fell; he stopped to pick ’em up, and the car swep’ down on him. Alice see his danger, she jumped to save him, only to be struck down herself.

Wall, what tongue of men or angels shall describe the seen that follered and ensued.

Martin layin’ in a dead faint, like death to all appearance—and it is blood relation to it. Little Adrian layin’ white and cold on a couch in the reception-hall, where the men had reverently laid him, right under the picter of that Eastern mother.

The agony in her dark face seemed to be for him, too—the fair-haired child of the race who condemn their barbarity, and practise worse.

And Alice a-layin’ white and onconscious, but breathin’ still, in her own room. One round, white arm a-hangin’ broken by her side, and blood streamin’ from a cruel gash in her head.

Wall, the best doctors in the city wuz there in a few minutes. But all their genius and wisdom and learnin’ could not bring back the spark of life that had flown away from little Adrian’s body.

And then afterwards the clergyman come and whispered consolin’ words to Martin in his darkened chamber.

But not all the preachin’ since Adam can make death other than death.

Martin didn’t want the clergyman—he wanted to be alone. He wouldn’t see anybody, and he lay still and cold after his senses come back—so still and cold that the doctors feared for his sanity, and even for his life.

The first glimpse of interest he showed wuz when they told him that there wuz a chance for Alice to live.

He turned his face towards the wall (so the nurse told me, a good, faithful creeter with a strong breath, caused by stimulants, I believe).

A FAITHFUL CREETER WITH A STRONG BREATH, CAUSED BY STIMULANTS, I BELIEVE.

Sez she, “I went to the foot of the bed and looked up, and see tears a-streamin’ down his white face. But I dare not speak to him,” sez she—“no, I dare not.”

Sez she, “His face had that look on it that it frightened me, and it gave me such a turn that I feel weak yet. I guess,” sez she, “I will take a drop to nerve me up. Don’t you want a drop of stimulant, too?” sez she.

“No, indeed,” sez I, “I don’t!”

“But,” sez I, “poor creeter, do everything you can for him, for the hand of the Lord has dealt sorely with him. And,” sez I, “I would gladly help him if I could, but I can do nothin’ but pray for him.”

Wall, there wuz a big funeral in the church where little Adrian had been baptized when he wuz a baby.

The minister, a very eloquent and high-priced one, preached a beautiful sermon about the inscrutable mysteries of our lives, and the mystery of the Providence who should take, in sech a onforeseen and onheard-of way the child of sech a man, who had spent his hull life for the good of the people—that angelic man, who wuz a-layin’ now in his palatial home at the pint of death.

These last words affected the congregation dretfully. A maiden jest behind Martin’s pew and a widder jest in front (who both had hopes) sallied away and partially fainted, and the widder had to be borne out by the sexton.

And as she wuz heavey, it bore hard on him. The old maid revived in time to see the widder carried out. Widders always will go further and resk more than the more single ones.

And the maiden wuz wroth for fear that Martin should hear of it that she didn’t go so fur herself as the widder did.

I myself didn’t faint nor shed tears. I sot up straight in that luxurious pew and kep’ a-sayin’ in my heart—

“Oh, God help that wretched man! God help and comfort him, for nothin’ else can!”