CHAPTER I.

TRAINS OF RETROSPECTION.

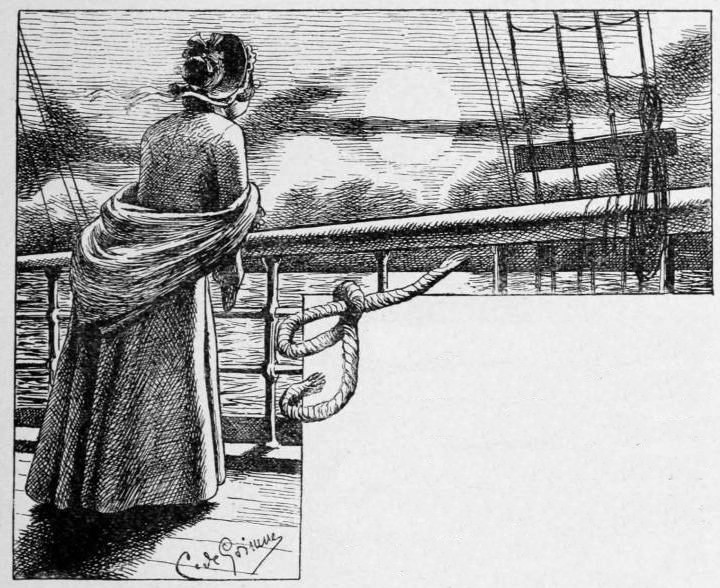

Twilight on the broad ocean! Smooth, wild waste of blue-gray waters stretchin’ out as fur as the eye could reach on every side.

In the east a silvery moon hangin’ low and a shinin’ path leadin’ up to it. In the west Mars a-dazzlin’ bright over a pale pink sky, with streaks of yeller and crimson a-layin’ stretched acrost it, like bars put up by angel hands a-fencin’ in their world from ourn.

Now in a sunset in Jonesville it might seem as if you could put on your sun-bunnet and stride off over hills and valleys and at las’ reach the Sunset Land, and peek over the bars and ketch a glimpse of what wuz beyend.

It would seem amongst the possibles.

But here—oh! how fur-off, illimitable, unaproachable, duz that fur-off glory look!

And Mars seemed to wink that red eye of hisen at me mockin’ly as I strained my eyes over the long watery plain, as if to say—“The time has been when you wuz free to roam round, a-walkin’ off afoot; you may have gloated over me in your free thoughts and said—

“You are fixed and sot up there, while I am free to soar and sail. Now, haughty female mortal, your wings are clipped—the time has come when your walkin’ afoot and roamin’ round is stopped.”

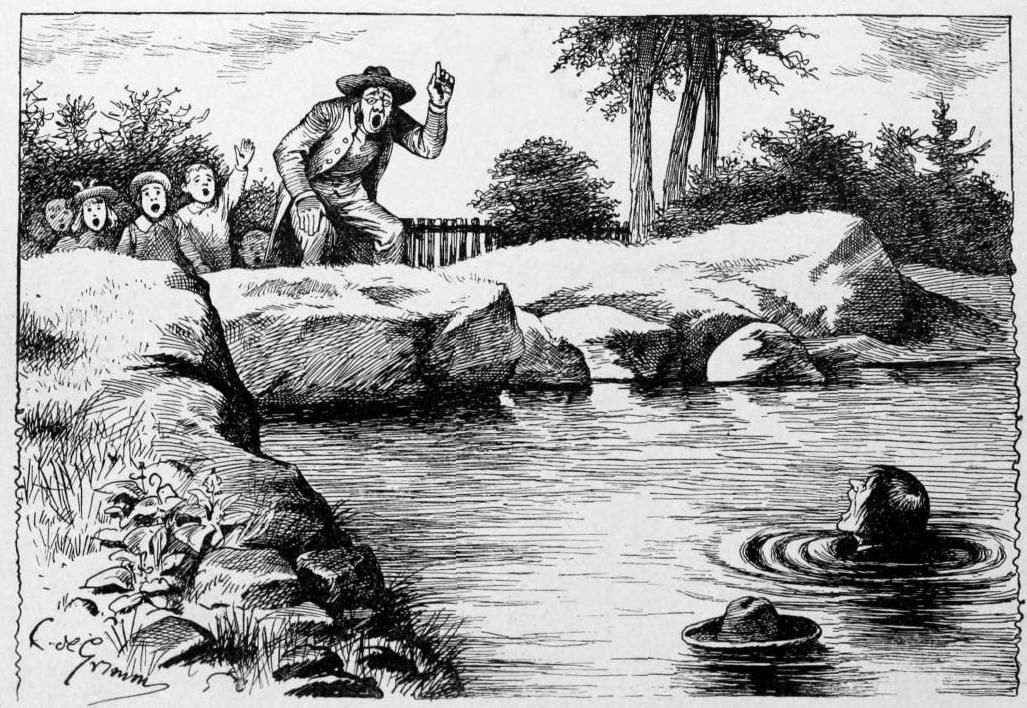

To think that I myself, Josiah Allen’s Wife, should find myself on the Atlantic a-hangin’ onto the gunwale of the ship with one hand, and a-lookin’ off over the endless waters below and all round me, and a-thinkin’ if I should trust myself to step out onto its heavey, treacherous surface where should I go to, and when, and why! I, Samantha, who had ever been ust to slippin’ on my sun-bunnet and runnin’ into Miss Bobbettses, or out into the garden, or out to the hen-house for eggs, or down into the orchard, or the wood paster for recreation or cowslips.

To think that I wuz thus caged up as it were, my restless wings (speakin’ in metafor) folded in such clost quarters, with no chance (to foller up the metafor) of floppin’ ’em to any extent.

Oh! where wuz I? The thought wuz full of or. Why wuz I? This thought brung on trains of retrospection.

As I sot in my contracted corner of the aft fore-castle deck, and Night wuz lettin’ down, gradual, her starry mantilly over me and the seen, as erst it did over me as I sot in the sweet, restful door-yard at Jonesville. (Dear seen, shall I ever see thee agin?)

I will rehearse the facts that led to my takin’ this onpresidented step.

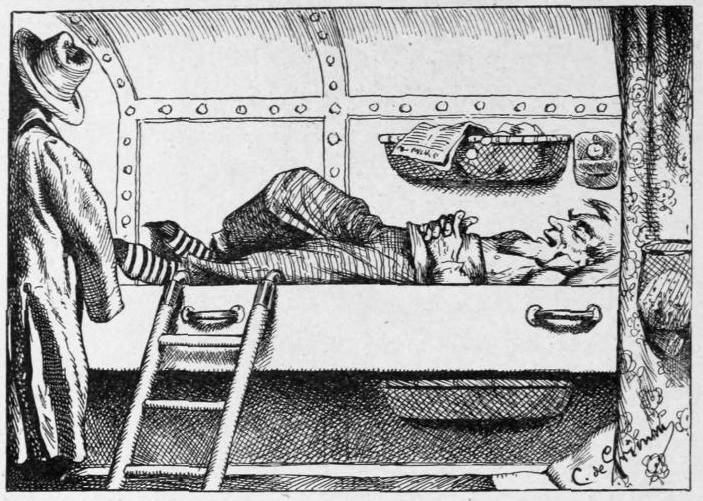

My pardner is asleep in his narrer bunk, or ruther on one of the shelves in our cell, that are cushioned, and on which our two forms nightly repose.

ASLEEP IN HIS NARRER BUNK.

He is at rest. The waves are asleep, or pretty nigh asleep, the night winds are hushed, and all Nater seems to draw in her breath and wait for me as I tell the tale.

I will begin, as most fashionable novelists do, with a verse of poetry——

“Backward, turn backward (as fur as Jonesville), Oh Time, in thy flight—

Make me (a trusty, short-winded, female historian) jest for to-night.”

It wuz now goin’ on three years sence Uncle Philander Smith’s son, Philander Martin, named after his Pa and his Uncle Martin, writ a line to me announcin’ his advent into Jonesville. And in speakin’ of Philander I shall have to go back, kinder sideways, some distance into the past to describe him.

Yes, I will have to lead the horse fur back to hitch it on properly to the wagon of my history, or mebby it would be more proper, under the circumstances, to say how fur I must row my little personal life-boat back to hitch it onto the great steamer of my statement, in order that there shall be direct smooth sailin’ and no meanderin’.

Wall, with the first paddle of my verbal row-boat, I would state—

(And into how many little still side coves and seemin’ly wind-locked ways my little life-boat must sail on her way back to be jined to the great steamer, and how I must stay in ’em for some time! It can’t be helped.)

Yes, it must have been pretty nigh three years ago that we had our first letter from P. Martyn Smythe.

He is my second cousin on my own side. And he sot out from Spoonville (a neighborin’ hamlet) years ago with lots of ambition and pluck and energy, and about one dollar and seventy-five cents in money.

Uncle Philander, his father, had a big family, and died leavin’ him nothin’ but his good example and some old spectacles and a cane.

He wuz brung up by his Uncle Martin, a good-natered creeter, but onfaculized and shiftless.

Young Martin never loved to be hampered, and after he got old enough to help his uncle, he didn’t want to be hampered with him, so he packed up his little knapsack and sot out to seek his fortune, and he prospered beyend any tellin’, bought some mines, and railroads, and things, and at last come back East and settled down in a neighborin’ city, and then got rid of several things that he found hamperin’ to him. Amongst ’em wuz his old name—now he calls it “Smythe.”

Yes, he got rid of the good, reliable old Smith name, that has stood by so many human bein’s even unto the end. And he got rid, too, of his conscience, the biggest heft of it, and his poor relations.

For why, indeed, should a Bill or a Tom Smith claim relationship with a P. Martyn Smythe?

Why, indeed! He got rid of ’em all in a heap, as it were, a-ignorin’ “the hull kit and bilein’ of ’em,” as Aunt Debby said.

“Never seen hide nor hair of any of ’em, from one year’s end to the other,” sez Aunt Debby.

As to his conscience, he got rid of that, I spoze, kinder gradual, a little at a time, till to all human appearance he hadn’t a speck left, of which more anon.

But there wuz a little of it left, enough to leven his hull nater and raise it up, some like hop yeast, only stronger and more spiritual (as will also be seen anon).

Wall, he never seemed to know where his cousin, she that wuz Samantha Smith, lived, and his neck seemed to be made in that way—kinder held up by his stiff white collar mebby—that it held his head up firm and immovable, so’s he didn’t see me nor my Josiah when he’d meet him once in a great while at some quarterly meetin’ or conferences and sech.

I guess that neck of hisen carried him so straight that he couldn’t seem to turn it towards the old Smith pew at all.

And then he wuz dretful near-sighted, too; his eyes wuz affected dretful curous.

Uncle Mart Smith, the one P. Martin wuz named after, atted him about it, for he wuz his own uncle, and dretful shiftless and poor, but a Christian as fur as he could be with his nateral laziness on him.

As I say, he partly brung Martin up. A good-natered creeter he wuz. And one day he walked right up and atted P. Martyn Smythe as to why he never could see him.

And P. Martyn sed that it wuz his eyesight; sez he, “I’m dretful near-sighted.”

It made it all right with Uncle Martin, but his wife, Aunt Debby, she sed, “Why can he see bishops and elders so plain?”

“Wall,” sez Uncle Mart, “it is a curous complaint.” And she sez—

“’Tain’t curous a mite; it’s as nateral as ingratitude, and as old as Pharo.”

And she and Uncle Mart had some words about it.

Wall, his eyesight seemed to grow worse and worse so fur as old friends and relations wuz concerned, till all of a sudden—it wuz after my third book had shook the world, or I spoze it did; it kinder jarred it anyway, I guess—wall, what should that man, P. Martyn, do, but write to me and invite me to the big city where he lived.

Sez he, “Relations ort to cling closter to each other;” sez he, “Come and stay a week.”

I answered his note, cool but friendly.

And then he writ agin, and asked me to come and stay a month. Agin my answer wuz Christian, but about as cool as well water.

And then he writ agin and asked me to come and stay a year with ’em. And he would be glad, he said, he and his two motherless children, if I would come and live with ’em always.

This allusion to the motherless melted me down some, and my reply wuz, I spoze, about the temperture of milk jest from the cow.

But I said that Duty and Josiah binded me to my home and Jonesville.

Wall, the next summer what should P. Martyn do but to write to me that he and Alice and Adrian, his two children, wuz a-comin’ to Jonesville, and would we take ’em in for a week? He thought his children needed fresh air and a little cossetin’.

Wall, to me, Josiah Allen’s wife, who has brung up almost numberless lambs and chickens by hand as cossets, this allusion to “cossetin’” melted me so and warmed up my nater, that my reply wuz about the temperture of skim milk het for the calves.

So they come.

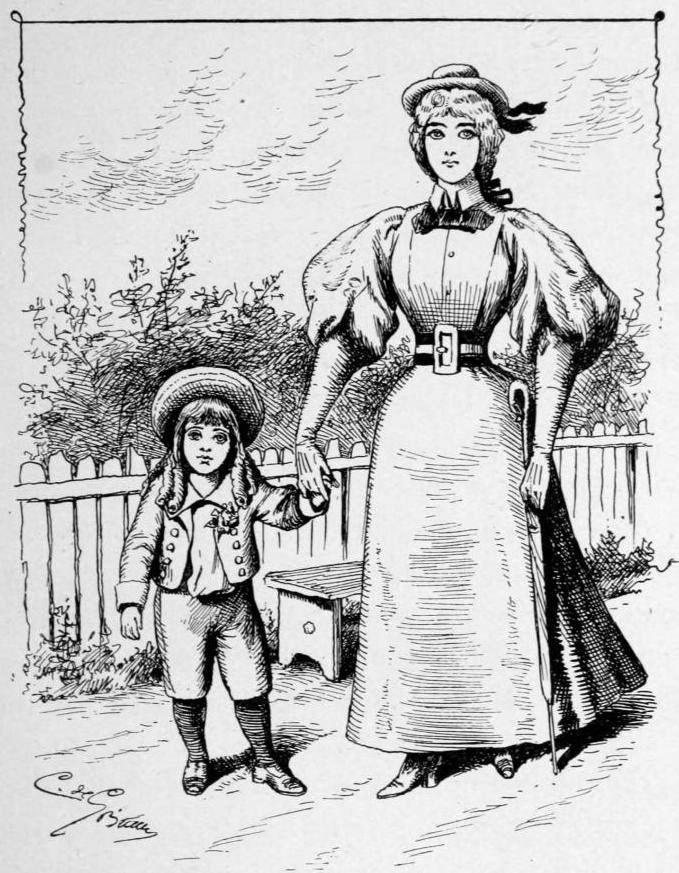

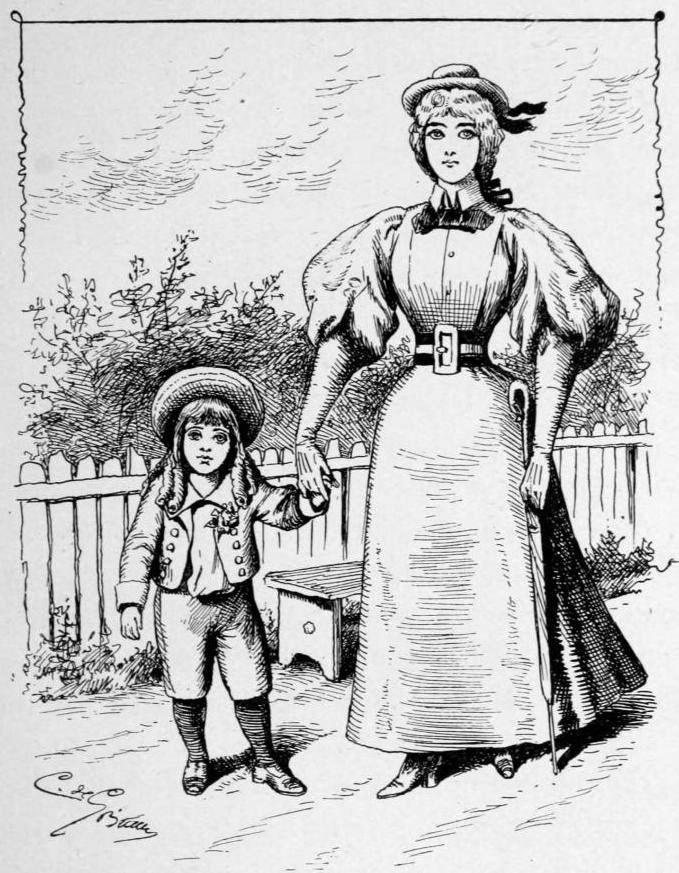

And indeed I said then what I say now, and I’ll defy anybody to dispute me, that two prettier, winnin’er creeters never lived than them two children.

TWO PRETTIER, WINNIN’ER CREETERS NEVER LIVED THAN THEM TWO.

Alice wuz about sixteen then, and Adrian wuz about five, and wuzn’t they happy! My hull heart went out to ’em, and mebby it wuz that love atmosphere that wropped ’em completely round that made ’em grow so bright and cheerful and healthy.

There hain’t no atmosphere that is at the same time so inspirin’ and so restful as the heart atmosphere of love.

You can always tell ’em that breathe its rare, fine atmosphere by the radiance in their faces and the lightness of their step.

I loved them two children dearly. They wuz both as handsome as picters, Alice fair and slender and sweet as a white day lily, with big, happy blue eyes, and hair of the same gold color that her mother had had.

Adrian had long curls of that same wonderful golden hair, and his eyes wuz big, inspirin’, blue gray, and his lips always seemed to hold a happy secret. He had that look some way.

Though what it could be we couldn’t tell, for he talked pretty much all the time.

And the questions he asked would more’n fill our old family Bible, I’m sure, and I thought some of the time that the overflow would fill Foxe’s “Book of Martyrs.”

Why, one day we got old Uncle Smedley to mow our lawn while Adrian wuz there, and I felt sorry that I didn’t put down the questions that Adrian asked that perfectly deaf man as he trotted along in his little velvet suit by the side of the lawn mower.

But then I d’no as I’m sorry, after all, for paper is sometimes skurce, and I don’t believe in extravagance.

And how he did love poseys, most of all the English violets! We had a big bed of ’em, and he always had a bunch of ’em in his little buttonhole, and be a-pinnin’ ’em to my waist and Alice’s. And he would have a big bunch in his hand, and jest bury his face in ’em, as if he wuz tryin’ to take in their deep, sweet perfume through his pores as it wuz. And always a little, low vase that stood before his plate on the table would be full of ’em.

I wondered at it some, but found out that before he wuz born his sweet Ma had jest sech a passion for ’em, and always had her room full of ’em. And I kinder wondered if, in some occult way, she wuz a-keepin’ up the acquaintance with her boy by means of that sweet and delicate language that we can’t spell yet, let alone talkin’.

I d’no, nor Josiah don’t, but anyway Adrian jest seemed to live on ’em in a certain way, as if they satisfied some deep hunger and need in his inmost nater.

And he would sometimes make the old-fashionedest remarks I ever hearn, and praise himself up jest as though he wuz somebody else. Not conceited at all, but jest sincere and honest.

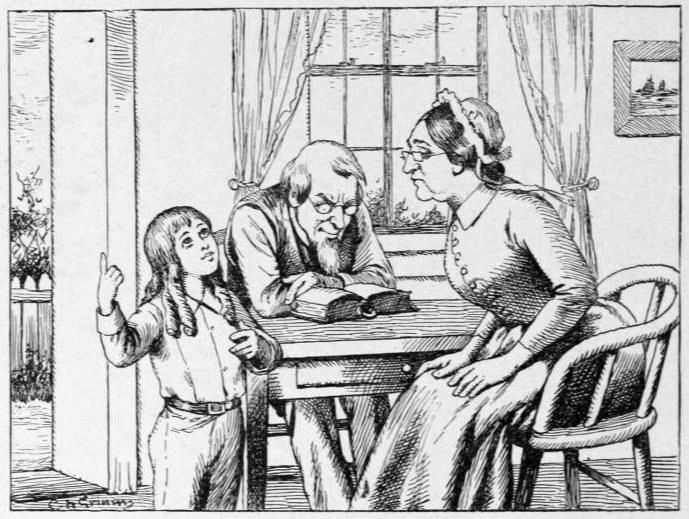

One day after family prayers, Josiah had been readin’ about the New Jerusalem, and I spoze Adrian’s curosity wuz rousted up, and sez he, “Aunt Samantha, where is Heaven? Is it up in the sky, or where is it?”

“AUNT SAMANTHA, WHERE IS HEAVEN? IS IT UP IN THE SKY?”

And I sez, “Sometimes I have thought, Adrian, it wuz right here all round us, if we could only see it.”

“I wonder if I could find it?” sez he, and he peered all round him in the old-fashionedest way I ever see.

Sez he, “I spoze my pretty Mamma is there; I guess she wants me dreadfully sometimes; I am a very bright little boy—I am very agreeable.”

“But,” I sez, “that hain’t pretty for you to talk so.”

“Why, Papa sez I am, and he sez I am his wise little partner, and my Papa knows everything that wuz ever known—he knows more than any other man in the world.”

And I sez to myself, “No, he don’t. He don’t know enough to be jest, from all I’ve hearn of his doin’s.”

But I didn’t wonder that Adrian thought as he did, or Alice either, for if there wuz ever a indulgent and lovin’ father on earth, it wuz Martin Smith.

Nothin’ wuz too good for his children. He adored ’em, and tried to be father and mother both to his motherless boy and girl. And money, so fur as they wuz concerned, flowed as free as water.

P. Martyn didn’t stay but a few days this time, but left the children two weeks and come back for ’em.

He stayed right to our house, and his eyesight, so fur as the other relations wuz concerned, wuz jest the same. He rode round considerable with his children, and writ about five thousand letters, and sent off and received about the same number of letters and telegrams, and said and assured us at the end of the three days he wuz there, that “it wuz so sweet for him to have sech a perfect rest.”

He didn’t tell us much about what wuz in the letters, though the last day that he wuz there he got sech a enormous batch of ’em that he daned to explain the meanin’ of ’em to Josiah and me, for we both had helped him to carry ’em in. Sez he, “There is no such thing as satisfying the masses.

“Now,” sez he, “I’ve built a line of trolley cars, that are the means of saving no end of time, for my drivers, if they don’t come up to the swift schedule time I have marked down for them, I discharge them at once.

“They are economical, much cleaner and swifter than horses, an invaluable saving of time. They are convenient, rapid, and cheap. Now you would think that would satisfy them, but no; because they run through the most populous streets of the city, and because once in awhile an accident takes place, what do they want? They want me to add further to the enormous expense I have already been subjected to, and buy some fenders to prevent accidents.”

“Wall, hain’t you goin’ to?” sez I.

“No,” sez he, “I am not. If I do, they will probably want some sashay bags to hang up in the cars, and some automatic fans to fan them with as they ride.” But I had been a-readin’ a sight about the deaths them swift monsters had caused, and I sez—

“Martin, life is dear, and it seems as if every safeguard possible ort to be throwed round the great public, between ’em and death.”

“But,” sez he, “it is impudent in them to demand anything further than what I’ve already done. Horses were always causing accidents.”

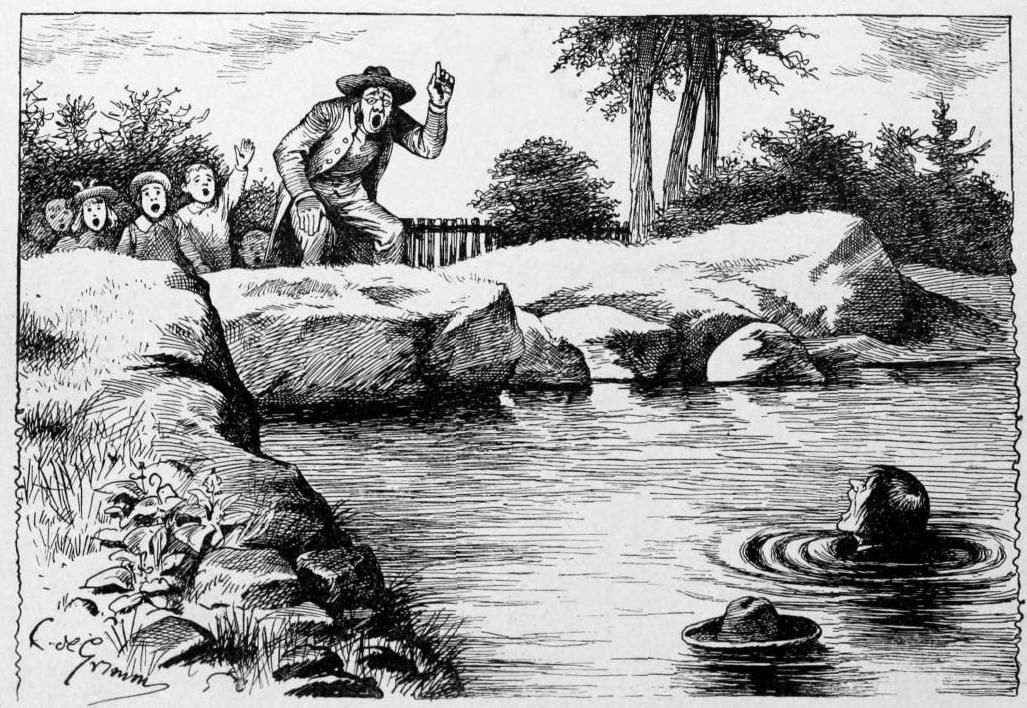

“Wall,” sez I, “when folks are in danger of death, it makes ’em impudent. Why, Deacon Garvin sassed the minister when he fell into the pond at a Sunday School picnic, and the minister told him to call on the Lord in his extremity.”

He sassed him and yelled out to him, “You dum fool, you, throw me a board!”

HE SASSED HIM AND YELLED OUT, “YOU DUM FOOL, YOU, THROW ME A BOARD!”

Sez I, “Dretful danger makes folks sassy.”

“Well, I won’t be to the expense of getting them,” sez he.

Sez I mildly, “You told Josiah Allen and me yesterday that you’d laid up two millions of dollars sence you had gone into this enterprise. Now, as a matter of justice, don’t you think that the public who have paid you two millions of their money have a right to demand these safeguards to life and limb?”

He waived off the question.

“Why,” sez he, “in all the last year there have not been more than fifty lives lost in our city from these cars, and considering the hosts that have been carried, considering the convenience, the swiftness, the rapidity, and etcetera—what is fifty lives?”

“IT DEPENDS ON WHOSE LIVES THEY BE.”

“Wall,” sez I, “it depends on whose lives they be. Now I know,” sez I, a-glancin’ at my pardner’s shinin’ bald head a-risin’ up like a full harvest moon from behind the pages of The World—

“I know one life that if it went down in darkness under them wheels, it would make the hull world black and empty. It would take all the happiness and hope and meanin’ out of this world, and change it into a funeral gloom.”

Sez I, “It would darken the world for all who love him.” And sez I, “Every one of them fifty that have gone down under them death chariots have left ’em who loved ’em. Hearts have ached and broken as they have looked at the mangled bodies and the emptiness of life faced ’em.” Sez I, “Them rollin’ billows of blackness have swept over the livin’ and the lovin’ every time them cruel wheels have ground a bright human life to death.

“They have mostly been children,” sez I, “and think of the anguish mother hearts have endured, and father love and pride—how it has been crushed down under the rollin’ wheels of death.

“Sometimes a father, who wuz the only prop of a family, has gone down. How cold the world is to ’em when the love that wropped ’em round has been tore from ’em! Sometimes a mother—what can take the place of mother love to the little ones left to suffer from hunger, and nakedness, and ignorance?”

“You’re imaginative, Cousin Samantha,” said he; but I kep’ right on onbeknown to me.

“Who will care for the destitute children left alone in the cold world with no one to care for ’em and help ’em?”

“I’ll give ’em some money,” said little Adrian, who’d been leanin’ up aginst my knee and listenin’ to our talk, with his big, earnest eyes fixed on our faces.

“I’ll give ’em the gold piece that papa gave me yesterday.”

He had gin him a twenty dollar gold piece, for I see it.

“I’ll give ’em all I’ve got—I’ll work for that poor woman who lost her little boy—I’ll work for her and help her.”

“Who’ll work for me?” sez Martin. “You’re to be my partner, my boy; remember that. You’re my little partner now—half of all I own belongs to you.”

“And I will give it all to them,” sez Adrian.

But Martin went right on—“You are to be president of this company when I am an old man; you’re to work for me.”

“But I’ll work for those poor people, papa,” sez Adrian, and as he said this he looked way off through his father’s face, as he sot by the open window, to some distance beyend him. And his eyes, jest the color of that June sky, looked big and luminous.

“I’ll work for them, papa,” and as he spoke a sudden thrill, some like electricity, only more riz up like, shot through my soul, a sudden and deep conviction that he would work for ’em—that he would in some way redeem the old Smith name from the ojium attachin’ to it now as a owner of them Herod’s Chariots and a Massacreer of Innocents. But to resoom.

All the next day Adrian kep’ talkin’ about it, how he wuz goin’ to be his papa’s pardner, and how he wuz a-goin’ to work for poor folks who had lost their little children, and wanted so many things.

And the questions he asked me about ’em, and about poor folks, though wearisome to the flesh, wuz agreeable to the sperit.

Wall, Martin called him so much from day to day—“My little partner,” that we all got into the habit on’t, and called him so through the day.

And every evenin’ he would come to me and say—“Good-night, Aunt Samantha, good-bye till mornin’.”

And I would kiss him earnest and sweet, and say back to him, “Good-night, little pardner, till mornin’.”

And after he went home, Josiah and I would talk about him a sight, and wonder what the little pardner wuz doin’, and how he wuz lookin’ from day to day. And I would often go into the parlor, where his picter stood on the top shelf of the what-not, and stand and look dreamily at it. There he wuz in his little black velvet suit and a big bunch of English violets pinned on one side. The earnest eyes would look back at me dretful tender like and good. The mouth that held that wonderful sweet and sort o’ curous expression, as if he wuz thinkin’ of sunthin’ beautiful that we didn’t know anything about, would sort o’ smile back at me.

And he seemed to be a-sayin’ to me, as he said that day a-lookin’ out into the clear sky—

“I’ll work for them poor people!”

And I answered back to him out loud once or twice onbeknown to me, and sez I, “I believe you will, little pardner.”

And Josiah asked me who I wuz a-talkin’ to. He hollered out from the kitchen.

And I sez, “Ahem—ahem,” and kinder coughed. I couldn’t explain to my pardner jest how I felt, for I didn’t know myself hardly.

Wall, it run along for some time—Martin a-writin’ to me quite often, always a-talkin’ about his little pardner and Alice, and how they wuz a-gittin’ along, and a-invitin’ us to visit ’em.

And at last there came sech a pressin’ invitation from Alice to come and see ’em that I had to succumb.

But little, little did I ever think in my early youth, when I ust to read about Solomon’s Temple and Sheba’s Splendor, and sing about Pleasures and Palaces, that I should ever enter in and partake of ’em.

Why, the house that Martin lived in wuz a sight, a sight—big as the meetin’-housen at Jonesville and Loontown both put together, and ornamented with jest so many cubits of glory one way, and jest so many cubits of grandeur another. Wall, it wuz sunthin’ I never expected to see on earth, and in another sphere I never sot my mind on seein’ carpets that your feet sunk down into as they would in a bed of moss in a cedar swamp, and lofty rooms with stained-glass winders and sech gildin’s and ornaments overhead, and furniture sech as I never see, and statutes a-lookin’ pale with joy, to see the lovely picters that wuz acrost the room from ’em; and more’n twenty servants of different sorts and grades.

Why, actually, Josiah and I seemed as much out of place in that seen of grandeur as two hemlock logs with the bark on ’em at a fashionable church weddin’.

And nothin’ but the pure love I felt for them children, and their pure love for me, made me willin’ to stay there a minute.

Martin wuz good to us, and dretful glad to have us there to all human appearance; but Alice and Adrian loved us.

And I hadn’t been there more’n a few days before I see one reason why Alice had writ me so earnest to come—she wuz in deep trouble, she wuz in love, deep in love with a young lawyer, one who writ for the newspapers, too—

A man who had the courage of his convictions, and had writ several articles about the sufferin’s of the poor and the onjustice of rich men. And amongst the rest he had writ some cuttin’ but jest articles about the massacreein’ of children by them trolley cars, and so had got Martin’s everlastin’ displeasure and hatred.

The young man, I found out, wuz as good as they make anywhere; a noble-lookin’ young feller, too, so I hearn.

Even Martin couldn’t say a word aginst him, for, in the cause of Duty and Alice, I tackled him on the subject. Sez I, “Hain’t he honest and manly and upright?”

And he had to admit that he wuz, that he hadn’t a vice or bad habit, and wuz smart and enterprisin’.

I held him right there with my eye till I got an answer.

“But he is a fool,” sez he.

Sez I, “Fools don’t generally write sech good sense, Martin.”

Sez he wrathfully, “I knew your opinions—I expected you’d uphold him in his ungrateful folly.

“But he has lost Alice by it,” sez he; “for I never will give my consent to have him marry her.”

Sez I, “Then you had never ort to let him come here and have the chance to win her heart, and now break it, for,” sez I, “you encouraged him at first, Martin.”

“I know I did,” sez he—“I thought I had found one honest man, and I had decided on giving all my business into his hands. It would have been the making of him,” sez he; “but he has only himself to blame, for if he had kept still he would have married Alice, but now he shall not.”

Sez I, “Alice thinks jest as he duz.”

“What do women know about business?” he snapped out, enough to take my head off.

“If wimmen don’t know anything about bizness, Martin, I should think you’d be glad to know, in case you left Alice, that she and her immense fortune wuz in the hands of an honest man.

“And I want you to consent to this marriage,” sez I, “in a suitable time—when Alice gits old enough.”

“I won’t consent to it!” sez he—“the writer of them confounded papers never shall marry my daughter.”

“Why,” sez I, “there’s nothin’ harsh in the articles.” Sez I, “They’re only a strong appeal to the pity and justice of ’em who are responsible for all this danger and horrow!”

“Well,” sez he, “I’ve made up mind, and I never change it.”

Sez I, “I d’no whether you will or not.” Sez I, “This is a strange world, Martin, and folks are made to change their minds sometimes onbeknown to ’em.”

Wall, I didn’t stay more’n several days after this, when I returned to the peaceful precincts of Jonesville and my (sometimes) devoted pardner, and things resoomed their usual course.

But every few days I got communications from Martin’s folks. Alice writ to me sweet letters of affection, wherein I could read between the lines a sad background of Hope deferred and a achin’ heart.

And Adrian writ long letters to me, where the spellin’ left much to be desired, but the good feelin’ and love and confidence in ’em wuz all the most exactin’ could ask for.

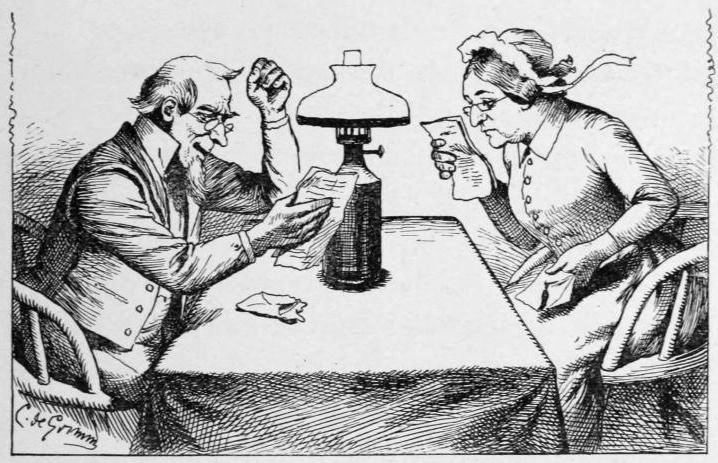

And occasionally Martin would write a short line of a sort of hurried, patronizin’ affection, and the writin’ looked so much like ducks’ tracts that it seemed as if our old drake would have owned up to ’em in a law suit.

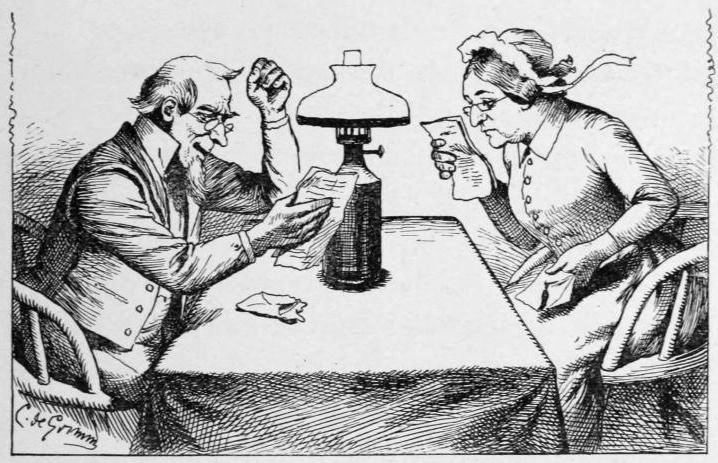

But Josiah and me would put on our strongest specks, and take the letter between us, and hold it in every light, and make out the heft on it.

JOSIAH AND ME PUT ON OUR STRONGEST SPECKS