THE THREE BROTHERS

I.

There was once upon a time an old man whose family consisted of his wife and three sons. They were exceedingly poor, and finding that they could not possibly all live at home, the three sons went out into the world in different directions to find some means of living. Thus the old man and his wife remained alone.

Having neither horses nor oxen, the old man was obliged to go every day to the forest for fuel, and carry home the firewood on his back.

On one occasion it was nearly evening when he started to go to the forest, and his wife, who was afraid to remain alone in the house, begged very hard to be permitted to go with him. He objected very much at first, but as she persisted in her entreaties, he at length consented to her following him, first bidding her, however, take good care to make the house-door safe, lest some one should break into the house.

The old woman thought the door would be safest if she took it off its hinges, and carried it away on her back. So she took it off and followed her husband as fast as she was able. The old man, however, was not angry when he saw how she had mistaken his words, and the manner she had chosen to make sure of the door; for, he reflected, there was little or nothing at all in the house for any one to steal.

When they had reached the forest the husband began to cut wood, and his wife gathered the branches together in a heap. Meanwhile it had got very late, and they were anxious as to how they should pass the night, seeing their own house was so far off that they would be unable to reach it before morning, and there were no houses in the neighbourhood where they could sleep. At last they observed a very tall and widely spreading pine-tree, and they resolved to climb up and pass the night on one of its branches.

The man got up first, and his wife followed him, drawing, with great difficulty, the door after her. Her husband advised her to leave the door on the ground under the tree; but she would not listen to him, and could not be persuaded to remain in the tree without her house-door. Hardly had they settled themselves on a branch, the old woman holding fast her door, before they heard a great noise, which came nearer and nearer.

They were excessively frightened at the noise, and dared neither speak nor move.

In a short time they saw a captain of robbers followed by twelve of his men, approach the tree; the robbers were dressed all alike, in gold and silver, and one of them carried a sheep killed and ready for roasting. When the old man and woman saw the band of robbers come and settle under the pine-tree in which they had themselves taken refuge they thought their time was come, and gave themselves up for lost.

As soon as the robbers had settled themselves, the youngest of them made a fire and put the sheep down to roast, whilst the captain conversed with the others. The sheep was already roasted and cut up, and the robbers had begun with great gaiety to eat it, when the old woman told her husband that she could not possibly hold the door any longer, but must let it fall. The old man begged her piteously not to let it go, but to hold it fast and keep quiet, lest the robbers should discover and kill them. The old woman said, however, that she was so exceedingly tired she could no longer by any possibility hold it. The old man, seeing it was no good talking about it, declared that, as he could not hold his corner of the door any longer when she had let go her corner, it was not worth while to complain, “since,” as he said, “what must be must be, and it is no use to be sorry for anything in this world.” Thereupon they both loosened their holds of the door at once, and it fell down, making a great noise—especially with its iron lock—as it fell from branch to branch.

The door made so much noise in falling, that the whole forest re-echoed with the sound.

The robbers, greatly astonished at the noise, and too frightened by the unexpected clashing above their heads to see what was the cause, took to their heels, without once thinking of the roast sheep they left behind, or of any of the treasures which they had brought with them. One of them alone did not run away far from the spot, but hid himself behind a tree, and waited to see what might come of so much noise.

The old couple, seeing the robbers did not return, came down from the tree, and, being exceedingly hungry, began to eat heartily; the old man all the time praising the wisdom of his wife in throwing down the door.

The robber who had hidden himself, seeing only the old people near the fire, came up to them, and begged to be allowed to share their meal, as he had not eaten anything for the last twenty-four hours. This they permitted, and spoke of all kinds of things, until the old man exclaimed suddenly to the robber, “Take care! you have a hair on your tongue! Do not choke yourself, for I have no means to bury you here!”

The brigand took this joke in earnest, and begged the old man to take the hair out of his mouth, and he would in return show him a cave wherein a great treasure was hidden. As he was describing the great heaps of gold ducats, thalers, shillings, and other coins which he said were in the cave, the old woman interrupted him, saying, “I will take the hair out of your mouth, without pay! Only put your tongue out and shut your eyes!” The robber very gladly did as she told him, and she caught up a knife and in a moment cut off a piece of his tongue. Then she said, “Well, now! I have taken the hair out!” When the robber felt what had been done to him he jumped up and down in pain, and at length ran away without hat or coat in the same direction as his companions had gone, shouting all the time, “Help! help! give me some plaster!” His companions, hearing imperfectly these words, misunderstood him, and thought he cried to them, “Help yourselves; here is the police-master!” especially as he ran as if the captain of police with a large force was at his heels. Accordingly, the robbers themselves ran faster and farther away.

Meanwhile the old couple thought it no longer safe to stay under the pine-tree, so they gathered up quickly all the money, whether gold or silver, which they could carry, and hurried back to their home. When they got there they found the hens of the neighbours had pulled off the thatch of their house; they were, however, the less sorry for this, since they had now money enough to build another and a better home. And this they did, and continued to live in their fine new house without once remembering their sons, who had been wandering about the world already some nine long years.

II.

In the meantime the sons had been working each in a different part of the world. When, however, they had been away from their home nine years, they all, as if by common consent, conceived an ardent desire to go back once more to their father’s house. So they took the whole of the savings which they had laid up in their nine years’ service, and commenced their journeys homewards.

On his travels the eldest brother met with three gipsies, who were teaching a young bear to dance by putting him on a red-hot plate of iron. He felt compassion for the creature in its sufferings, and asked the gipsies why they were thus tormenting the animal. “Better,” he said, “let me have it, and I will give you three pieces of silver for it!” The gipsies accepted the offer eagerly, took the three pieces of silver, and gave him the bear. Travelling farther on he met with some huntsmen who had caught a young wolf, which they were about to kill. He offered them, also three pieces of silver for the animal, and they, pleased to get so much, readily sold it. A little further still he met some shepherds, who were about to hang a little dog. He was sorry for the poor brute, and offered to give them two pieces of silver if they would give the dog to him, and this they very gladly agreed to.

So he travelled on homeward, attended by the young bear, the wolf-cub, and the little dog. As all his nine years’ savings had amounted only to nine pieces of silver, he had now but a single piece left.

Before he reached his father’s house he met some boys who were about to drown a cat. He offered them his last piece of money if they would give him the cat, and they were content with the bargain and gave it up to him. So, at last he arrived at his home without any money, but with a bear, a wolf, a dog, and a cat.

Just so, it had happened with the other two brothers. By their nine years’ work they had only saved nine pieces of silver, and on their way home they had spent them in ransoming animals, exactly as the eldest brother had done.

Soon after they had returned, the old father died. Then the three brothers consulted together, and decided to invest part of the money, which their father and mother had got from the robbers, in the purchase of four horses and one grass-field.

A few days later they all went into the fields to bring in the hay which the two elder ones had mown. They found, however, hardly the third part of the hay which they had left. At this they wondered greatly, and looked about to see who had stolen it; but, finding no one, after a little while they took up what was left and returned home.

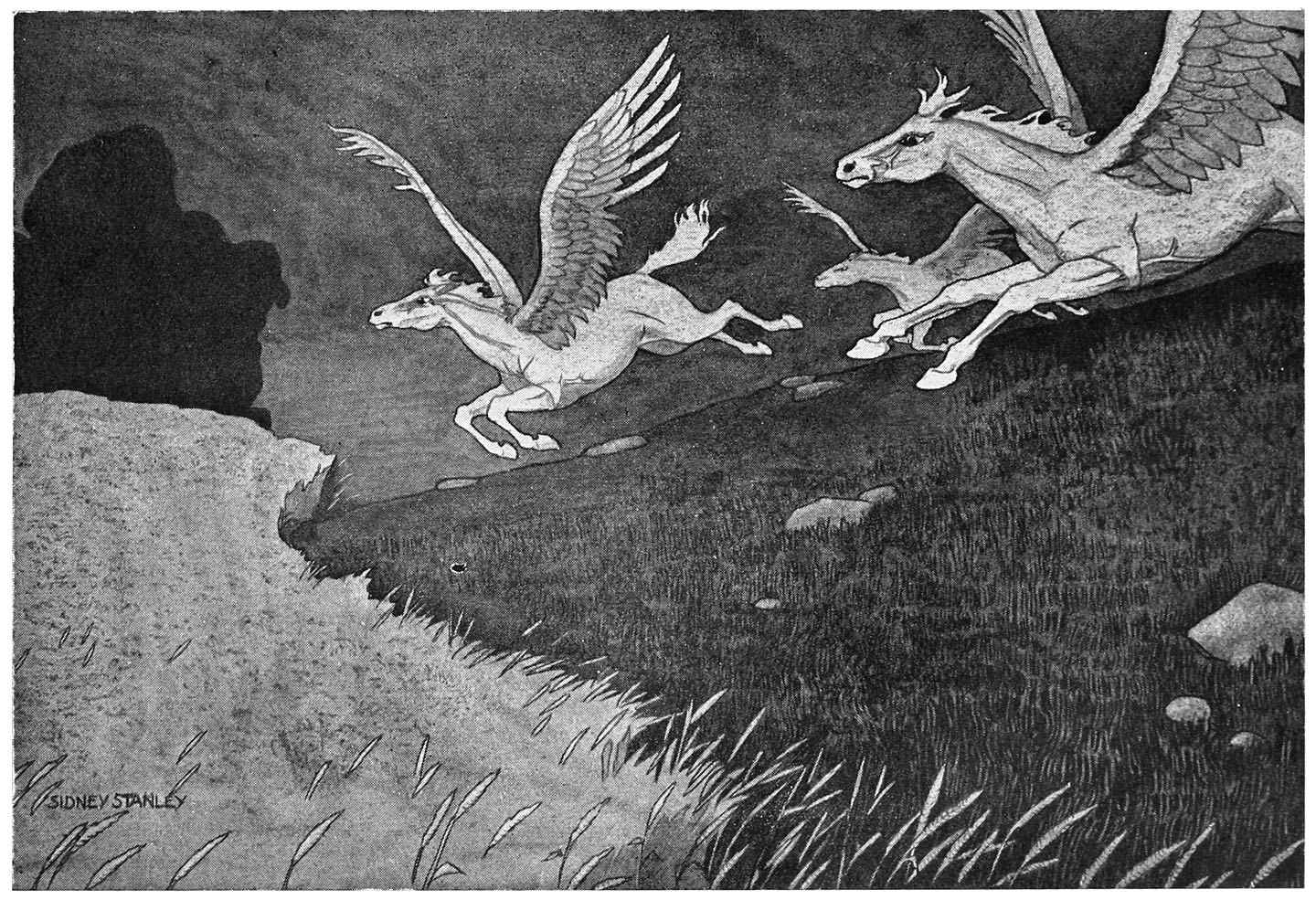

“Three winged horses came into the field.”

At length the year, on which all this had happened, passed away. The next year, however, they dared not leave their mown grass unwatched. So they discussed which of them should first keep guard. Each of them offered to do it; but, at last, they agreed that the youngest brother should begin to watch. So he prepared himself, and, at night, went out into the field. Having come there, he climbed up into a tree and resolved to remain there until daybreak. About midnight he heard a great noise and shouting, which frightened him so much that he dared not stir at all. Some creatures came into the field and ate up most of the hay, and what they did not eat they tossed about and spoiled, so that it was fit for nothing. When daylight came, the youngest brother came down from the tree and went home, to tell what he had seen.

So that year they had no hay.

Next year, when hay harvest came, the three brothers took counsel together how to preserve their hay. The second brother now volunteered to watch in the field, and seemed quite sure he would be able to save the hay. Accordingly he went, and climbed into the tree, just as his brother had done the previous year. About midnight three winged horses came into the field with a company of fairies. The winged horses began to eat the newly mown hay, and the fairies danced over it. After the greater part of the hay had been eaten by the horses, and all the rest had been spoiled by the dancing of the fairies, the whole company left the field, just as day began to dawn. The watcher in the tree had witnessed all this; he was, however, too frightened to do anything—indeed, he hardly dared to move. When he went home, he told his brothers all that he had seen; at which they were sad, since this year again they would have no hay.

However, the time passed, and the third summer came on. Again the three brothers cut the grass in their meadow, and consulted together anxiously how they should manage to keep their new hay.

At length it was settled that it was now the turn of the eldest brother to keep watch. If he, also, failed to save the hay, it was agreed that they should divide amongst them the little property which they had left, and go out again, separately, to seek their fortunes in the world, seeing they had no luck in their own country.

As had been agreed upon, the eldest brother now went out into the field at night; but, instead of going up into the tree as his brothers had done, he lay quietly down on a heap of hay, and waited to see what would happen. About midnight he heard a great noise, afar off, and, by-and-by, a troop of fairies, with three winged horses, came straight towards the place where he lay. Having got there, the fairies began to dance, and the horses to eat the hay, and canter about. The eldest brother looked on, and, at first, felt much afraid, and wished heartily the whole company would go away without seeing him. As, however, they seemed in no hurry to do this, he considered what he should do, and, at length, decided that it would be worth while to try to catch one of the three horses. So, when they came near him, he jumped on the back of one of them, and clung fast to it. The other two horses instantly ran away, and the fairies with them.

The horse which the eldest brother had caught tried all sorts of tricks to throw off his unwelcome rider, but he could not succeed. Finding all his attempts to free himself quite useless, at last he said, “Let me go, my good man, and I will be of use to you some other time.” The man answered, “I will set you free on one condition; that is, you must promise never more to come in this field; and you must give me some pledge that you will keep your promise.”

The horse gladly agreed to this condition, and gave the man a hair from his tail, saying, “Whenever you happen to be in need, hold this hair to a fire, and I will instantly be at your service.”

Thereupon the horse went off, and the eldest brother returned home. His brothers had waited impatiently for his return, and, when they saw him, pressed him immediately to tell them all that had happened. So he told everything, except that he had got a hair from the horse’s tail, because he did not believe that the horse would keep his promise and come to him in his need. The two younger brothers, however, had no confidence that the fairies and winged horses would fulfil their promise and never come again to ruin their hay-field, so they proposed that the property should be at once divided, and that they should separate. The eldest brother tried to persuade them to remain at least one other year longer, to see what would happen; he was not able, however, to succeed in this. Accordingly they divided the remnant of their property, took each their animals, that is, each his bear, his wolf, his dog, and his cat, and left their home, for the second time, to seek their fortunes in the world.

The first day they travelled together, but the second day they were obliged to separate, because having come to a crossway, and trying to keep on the same path, they found they could not take a step forward so long as they were together. They therefore left that path and tried another; it was, however, of no use, for they could not move a step forward as long as they were together; and when they tried the third path, the same happened there also. So they tried if two of them could go on in one road if one of them went before and the other behind. But this also they were unable to do; they could not get on one step, try as hard as they would, so nothing was left them but to separate and each of them to go alone by a different road. They were exceedingly sorry to part, but could not help themselves.

Before the brothers separated, the eldest brother said, “Now, brothers, before we part, let us stick our knives in this oak-tree; as long as we live our knives will remain where we stick them; when one of us dies, his knife will fall out. Let us, then, come here every third year to see if the knives are still in their places. Thus we shall know something, at least, about each other.” The other two agreed to this, and, having stuck their knives in the oak-tree, and kissed each other, went, each one his own way, taking his animals with him.

III.

Let us first follow the youngest brother in his wanderings. He travelled, with his attendant animals, all that day and the following night without stopping, and the next day saw before him a king’s palace, and went straight towards it. Having been taken into the presence of the king, he begged his Majesty to employ him in watching his goats. The king consented to take him as goat-herd, and from that day he had the charge of the king’s goats and lived on thus quietly for a long time.

One day the new goat-herd chanced to drive his flock to a high hill, not far from the king’s palace. On the summit of the hill there was a very tall pine-tree, and the instant he saw it he resolved to climb up and look about from its top on the surrounding country. Accordingly, he climbed up, and enjoyed exceedingly the extensive and beautiful prospect. As he looked in one direction he saw, a long way off, a great smoke arising from a mountain. The moment he saw the smoke he fancied that one of his brothers must be there, as he thought it unlikely that anyone else would be in such a wilderness. So he resolved at once to give up his place of goat-herd, and travel to the mountain which he had seen in the distance. Coming down from the tree, therefore, he immediately collected his goats, which was a very easy task for him to do, since he had such good help in his bear, his wolf, his dog, and his cat.

No sooner had he reached the palace than he went straight to the king and said, “Sir, I can no longer be your Majesty’s goat-herd. I must go away, for I saw to-day a smoking mountain, and I believe that one of my brothers is there, and I wish to go and see if this be so. I therefore beg your Majesty to pay me what you owe me, and to let me go!” All this time he thought the king knew nothing about the smoking mountain.

When he had said this, however, the king immediately began to advise him on no account to go to the mountain—for, as he assured him, whoever went there never came back again. He told him that all who had gone thither seemed at once to have sunk into the earth, for no one ever heard anything more about them. All the king’s warnings and counsels, however, availed nothing; the goat-herd was bent on going to the smoking mountain, and looking after his two brothers.

After he had made all preparations for the journey he set out, accompanied, as usual, by his four animals. He went straight to the mountain; but, having got there, he could not at first find the fire. Indeed, he had trouble enough before he discovered it. At length, however, he found a large fire burning under a beech tree, and went near it to warm himself. At the same time he looked about on all sides to see who had made the fire. After looking about some time he heard a woman’s voice, and upon his looking up to see whence the sound came, he saw an old woman sitting on one of the branches above his head. She sat huddled together all of a heap, and shaking with cold.

No sooner had he discovered her than the old woman begged him to allow her to come down to the fire and warm herself a little. So he told her she might come down and warm herself as soon as she pleased. She answered, however, “Oh, my son, I dare not come down because of your company. I am afraid of the animals you have with you—your bear, and wolf, and dog, and cat.”

At this he tried to reassure her and said, “Don’t be afraid! They will do you no harm.” However, she would not trust them, so she plucked a hair from her head, and threw it down, saying, “Put that hair on their necks and then I shall not be afraid to come down.”

Accordingly the man took the hair and threw it over his animals, and in a moment the hair was turned into an iron chain which kept his four-footed followers bound fast together.

When the old woman saw that he had done as she desired, she came down from the tree and took her place by the fire. She seemed at first a very little woman; as she sat by the fire, however, she began to grow larger. When he saw this he was greatly astonished, and said to her, “But, my old woman, it seems to me that you grow bigger and bigger!” Thereupon she answered, shivering, “Ha! ha! no, no, my son! I am only warming myself!” But, nevertheless, she continued to grow taller and taller, and had already grown half as tall as the beech-tree. The goat-herd watched her growing with wide-open eyes, and, beginning to get frightened, said again, “But really you are getting a fearful size, and are growing taller and taller every moment.”

“Ha, ha, my son,” she coughed and shivered, “I am only warming myself!” Seeing, however, that she was now as tall as the tallest beech-tree, and, fearing that his life was in danger, he called anxiously to his companions, “Hold her fast, my bear! Hold her fast, my wolf! Hold her fast, my dog! Hold her fast, my cat!” But it was all in vain that he called to them; none of them could move a step from his place. When he saw that, he endeavoured to run away, but found that he could no more move from his place than if he were fast chained to it. Then the old woman, seeing everything had gone on just as she wished, bent down a little, and, touching him with her little finger, said, “Go, you have lost your head!” and the self-same moment he turned to ashes. After that, she touched, with the little toe of her left foot, all his animals, one after the other, and they also turned at once to ashes as their master had done.

Having collected all the ashes she buried them under an oak-tree. Then as soon as she took the iron chain in her hand, it turned again into a hair, which she put back into its place on her head.

She had before done with many young and noble knights just as she had now done with this poor goat-herd.

The second brother, after serving a long time in a strange place, was seized with a great desire to go to the oak-tree at the cross-roads, where he had parted with his brothers, in order to see if their knives were still sticking in the tree. When he got there, he found the knife of his eldest brother still firmly fixed in the trunk of the oak, but his youngest brother’s knife had fallen to the ground. Then he knew that his younger brother was dead, or in great danger of death, and he resolved at once to follow the way he had gone and try to discover what had become of him. Going then along the same road which his younger brother had travelled, he came, on the third day, to the king’s palace, and went in and begged the king to take him into his service. Whereupon the king took him as goat-herd, exactly as he had taken before the youngest brother.

When the second brother had tended the king’s goats a long time, he one day drove them up a high hill, and, finding there a very tall pine-tree, resolved at once to climb up to its top and look about to see what kind of a country lay on the other side of the hill. When he had looked round a while from the tree he noticed a great volume of smoke rising from a mountain afar off, and the thought came at once to his mind that his brothers might be there. Accordingly, he came down quickly, collected his goats, and went back to the king’s palace, followed by his four companions, that is to say, by his bear, his wolf, his dog, and his cat. When he had reached the palace he went straight to the king, and begged him to pay him his wages at once, and to let him go to look after his brothers; for he had seen a smoke upon a mountain, and he believed they were there. The king tried in vain to dissuade him by telling him that none who went there ever came back; but all his Majesty’s words availed nothing. Thereupon, seeing he was decided on going, the king paid him what he owed him, and let him go.

He at once set out, and went straight to the mountain; but, when he got there, he was a long time before he could find any fire. At last, however, he found one burning under a beech-tree, and he went up to it to warm himself, wondering all the time who had made it, since he saw no one near. As he warmed himself he heard a woman’s voice in the tree above his head, and, looking up, saw there an old woman huddled up on a branch, and shaking with cold.

As soon as he saw her, the old woman asked him to let her come down and warm herself by the fire, and he told her she might come and warm herself as long as she liked.

She said, however, “I am afraid of the company which you have with you. Take this hair and lay it over your bear, and wolf, and dog, and cat, and then I shall be able to come down.”

So saying, she pulled a hair out of her head and threw it down. He laughed at her fears, and assured her that his companions would not hurt her; finding, however, notwithstanding all he said, that she was still afraid to come down from the tree, he at last took the hair and laid it on the beasts as she had directed. In an instant the hair turned into an iron chain, and bound the four animals fast together. Then the old woman came down, and took a place by the fire to warm herself. As the second brother watched her warming herself, he saw her grow bigger and bigger, until she had grown half as tall as the beech-tree.

Wondering greatly, he exclaimed, “Old woman, you are growing bigger and bigger.” “Hy, hy! my son,” said she, coughing and shivering, “I am only warming myself.” But when he saw that she was already as tall as the beech-tree, he became frightened, and called to his companions, “Hold her, my bear! hold her, my wolf! hold her, my dog! hold her, my cat.” They were none of them, however, able to move, so fast were they held together by the iron chain.

Seeing that, the old woman stooped down and touched him with her little finger, and he fell immediately into ashes. Then she touched the four animals, one after the other, with the little toe of her left foot, and they, also, crumbled to ashes.

No sooner had the old woman done this than she collected all the ashes in a heap and buried them under an oak-tree. As she had before done with the ashes of many a youthful knight and gentleman, so she did now with those of this poor simple man. Pity, if they were to die, that some more worthy means than one hair from the head of a miserable old woman had not brought about their deaths!

A very long time had passed, and yet the eldest brother never once thought of going back to the cross-roads where he had parted with his brothers. He was engaged in the service of a good and honest master, and, finding himself so well off, fancied that his brothers were the same. His master was an innkeeper, and the whole work of the servant was to prepare, morning and evening, the beds of the guests. He did his duty so well that his master thought of adopting him for his son, as he himself was childless.

One day a gentleman of great distinction came to pass the night at the inn, and the servant thought that the stranger looked remarkably like his youngest brother. He wished to ask him his name, but could not for shame, partly because he feared his brother would reproach him for having forgotten to go to the cross-roads; partly because the guest’s manners were so polished and his clothes were of fine silk and velvet; whereas he had left his brother very poorly clad, and of rustic manners.

As he thought of the likeness which the guest bore to his youngest brother, he considered that, in his travels about the world, his brother might have found wisdom, and by his wisdom might have succeeded in some way of business, and by his business might have gained money; and then, having got money, that it would be easy for him to get as fine clothes as the stranger wore. Reasoning thus, he took courage at last to ask the gentleman about his family, and at length grew bold enough to ask him plainly if he was not his brother.

This, however, the stranger quickly and positively denied, and asked, in return, about the servant’s family. To all the particulars which the servant gave him he listened with a smile.

Next morning, the guest left the inn very early; and when the servant went to arrange the bed in which he had slept, he found, under the pillow, a little stone.

He thought the stone must be valuable, having been in the possession of so rich a man, and yet he considered its loss could hardly be felt by one who went clothed in silks and velvets. He lifted it to his lips to kiss it, before putting it in his pocket; but the moment his lips touched it, two negroes started out and asked him, “What are your orders, sir?” He was frightened by the suddenness of their appearance, and answered, “I do not order anything.” Then the negroes disappeared, and he put the stone in his pocket.

The more he thought of this, the more he marvelled at the wonderful stone, and considered what he should do with it. By-and-by, in order to find out what the negroes could do, he took the stone out of his pocket, and raised it again to his lips. The moment he did so, the negroes reappeared, and asked him again, “What do you demand, sir?” He replied quickly, “I desire to have the finest clothes prepared for me, of which no two pieces must be made from the same kind of stuff.” In a very few moments the negroes brought him the most beautiful clothes possible; so fine indeed were they all, that he could not decide which piece was the most beautiful. Then, dismissing the negroes, who disappeared in the stone, he dressed himself. He was admiring the fine fit of his clothes, when his master came to the door of his room, and, seeing a stranger in such an exceedingly rich dress, said humbly, “Excuse me, sir, where do you come from?”

“From not far off,” the servant answered.

“Wait a moment, sir,” said the innkeeper; “I will call my servant to take your orders;” and, going outside, he called loudly for his servant.

Meanwhile, the servant quickly threw off his fine clothes and gave them back to