THE BEAR’S SON

Once upon a time a bear married a woman, and they had one son. When the boy was yet a little fellow he begged very hard to be allowed to leave the bear’s cave, and to go out into the world to see what was in it. His father, the Bear, however, would not consent to this, saying, “You are too young yet, and not strong enough. In the world there are multitudes of wicked beasts called men, who will kill you.” So the boy was quieted for a while, and remained in the cave.

But, after some time, the boy prayed so earnestly that the Bear, his father, would let him go into the world, that the Bear brought him into the wood, and showed him a beech-tree, saying, “If you can pull up that beech by the roots, I will let you go; but if you cannot, then this is a proof that you are still too weak, and must remain with me.” The boy tried to pull up the tree, but, after long trying, had to give it up, and go home again to the cave.

Again some time passed, and he then begged again to be allowed to go into the world, and his father told him, as before, if he could pull up the beech-tree he might go out into the world. This time the boy pulled up the tree, so the Bear consented to let him go, first, however, making him cut away the branches from the beech, so that he might use the trunk for a club. The boy now started on his journey, carrying the trunk of the beech over his shoulder.

One day as the Bear’s son was journeying he came to a field, where he found hundreds of ploughmen working for their master. He asked them to give him something to eat, and they told him to wait a bit till their dinner was brought them, when he should have some—for, they said, “Where so many are dining one mouth more or less matters but little.” Whilst they were speaking there came carts, horses, mules, and asses, all carrying the dinner. But when the meats were spread out the Bear’s son declared he could eat all that up himself. The workmen wondered greatly at his words, not believing it possible that one man could consume as great a quantity of victuals as would satisfy several hundred men. This, however, the Bear’s son persisted in affirming he could do, and offered to bet with them that he would do this. He proposed that the stakes should be all the iron of their ploughshares and other agricultural implements. To this they assented. No sooner had they made the wager than he fell upon the provisions, and in a short time consumed the whole. Not a fragment was left. Hereupon the labourers, in accordance with their wager, gave him all the iron which they possessed.

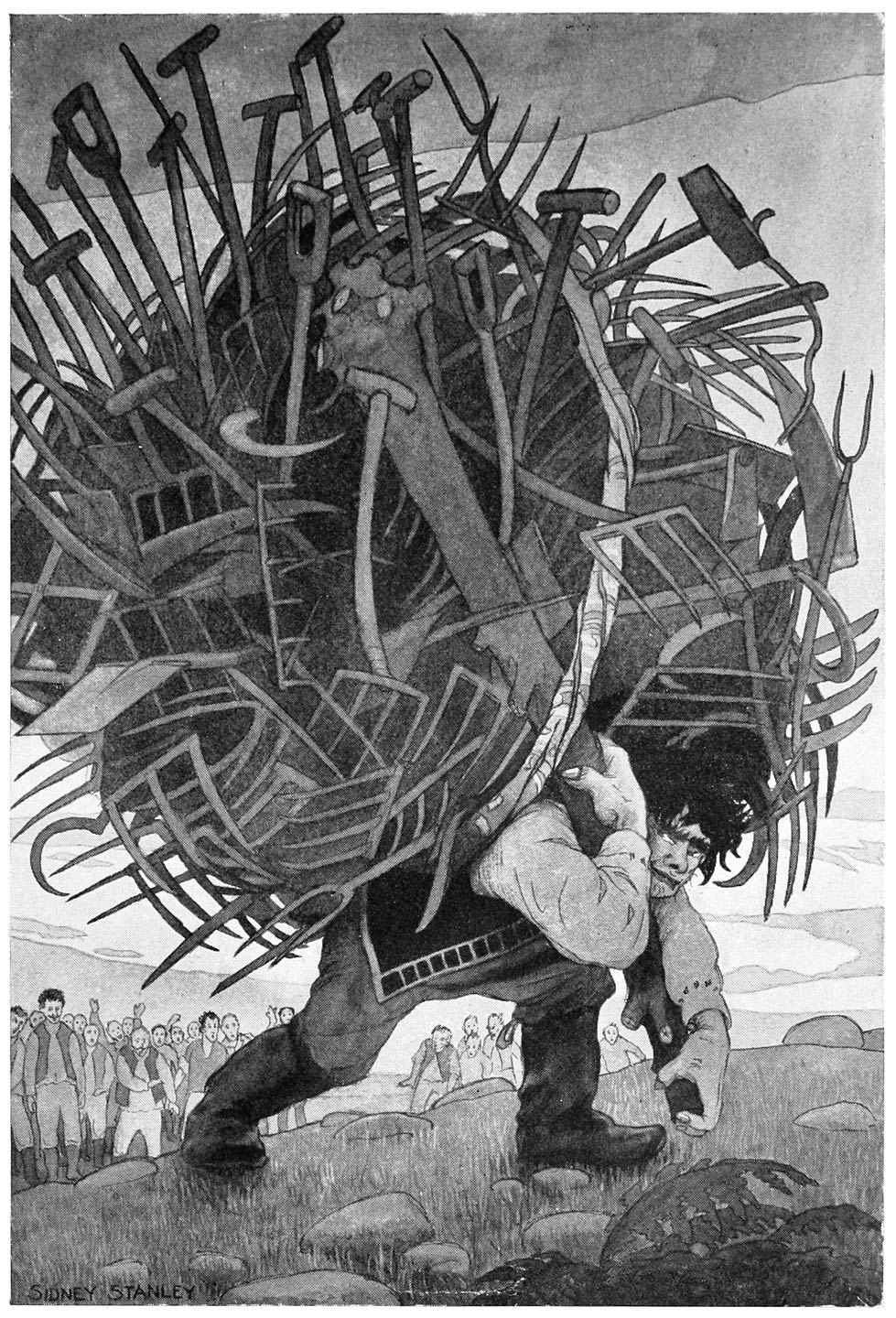

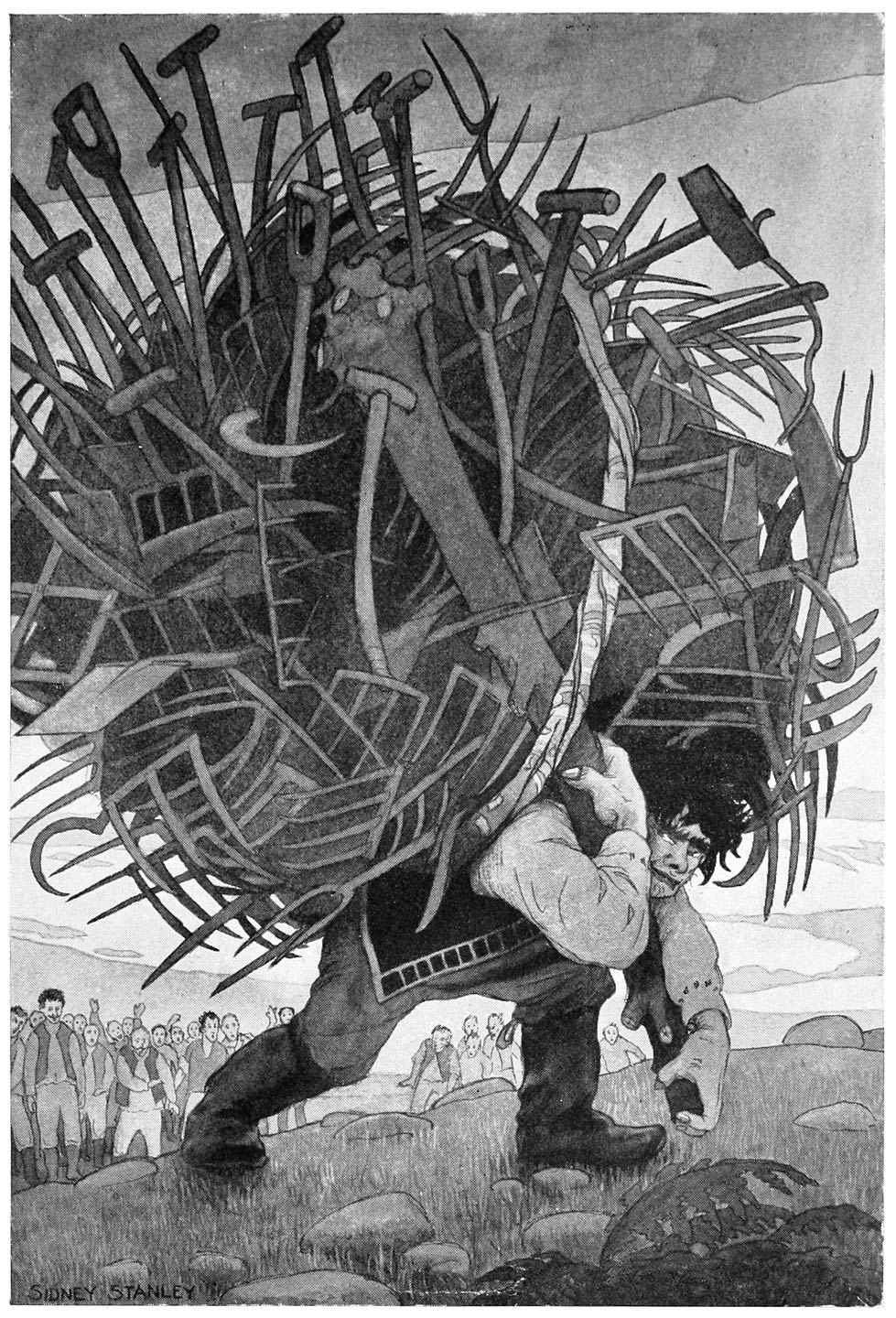

When the Bear’s son had collected all the iron, he tore up a young birch-tree, twisted it into a band and tied up the iron into a bundle, which he hung at the end of his staff, and, throwing it across his shoulder, trudged off from the astonished and affrighted labourers.

Going on a short distance, he arrived at a forge in which a smith was employed making a ploughshare. This man he requested to make him a mace with the iron which he was carrying. This the smith undertook to do; but, putting aside half the iron, he made of the rest a small, coarsely-finished mace.

The Bear’s son saw at a glance that he had been cheated by the smith. Moreover, he was disgusted at the roughness of the workmanship. He however took it, and declared his intention of testing it. Then, fastening it to the end of his club and throwing it into the air high above the clouds, he stood still and allowed it to fall on his shoulder. It had no sooner struck him than the mace shivered into fragments, some of which fell on and destroyed the forge. Taking up his staff, the Bear’s son reproached the smith for his dishonesty, and killed him on the spot.

Having collected the whole of the iron, the Bear’s son went to another smithy, and desired the smith whom he found there to make him a mace, saying to him, “Please play no tricks on me. I bring you these fragments of iron for you to use in making a mace. Beware that you do not attempt to cheat me as I was cheated before!” As the smith had heard what had happened to the other one, he collected his workpeople, threw all the iron on his fire, and welded the whole together and made a large mace of perfect workmanship.

“Tied up the iron into a bundle, which he hung at the end of his staff.”

When it was fastened on the head of his club the Bear’s son, to prove it, threw it up high, and caught it on his back. This time the mace did not break, but rebounded. Then the Bear’s son got up and said: “This work is well done!” and, putting it on his shoulder, walked away. A little farther on he came to a field wherein a man was ploughing with two oxen, and he went up to him and asked for something to eat. The man said, “I expect every moment my daughter to come with my dinner, then we shall see what God has given us!” The Bear’s son told him how he had eaten up all the dinner prepared for many hundreds of ploughmen, and asked, “From a dinner prepared for one person how much can come to me or to you?” Meanwhile the girl brought the dinner. The moment she put it down, the Bear’s son stretched out his hand to begin to eat, but the man stopped him. “No” said he, “you must first say grace, as I do!” The Bear’s son, hungry as he was, obeyed, and, having said grace, they both began to eat. The Bear’s son, looking at the girl who brought the dinner (she was a tall, strong, beautiful girl), became very fond of her, and said to the father, “Will you give me your daughter for a wife?” The man answered, “I would give her to you very gladly, but I have promised her already to the Moustached.” The Bear’s son exclaimed, “What do I care for Moustachio? I have my mace for him!” But the man answered, “Hush! hush! Moustachio is also somebody! You will see him here soon.” Shortly after a noise was heard afar off, and lo! behind a hill a moustache showed itself, and in it were three hundred and sixty-five birds’ nests. Shortly after appeared the other moustache, and then came Moustachio himself. Having reached them, he lay down on the ground immediately to rest. He put his head on the girl’s knee, and told her to scratch his head a little. The girl obeyed him, and the Bear’s son, getting up, struck him with his club over the head. Whereupon Moustachio, pointing to the place with his finger, said, “Something bit me here.” The Bear’s son struck him with his mace on another spot, and Moustachio again pointed to the place, saying to the girl, “Something has bitten me here!” When he was struck a third time he said to the girl angrily, “Look you! something bites me here!” Then the girl said, “Nothing has bitten you; a man struck you.”

When Moustachio heard that he jumped up, but the Bear’s son had thrown away his mace and run away. Moustachio pursued him, and though the Bear’s son was lighter than he, and had gained the start of him a considerable distance, he would not give up pursuing him.

At length the Bear’s son, in the course of his flight, came to a wide river, and found, near it, some men threshing corn. “Help me, my brothers, help—for God’s sake!” he cried; “Help! Moustachio is pursuing me! What shall I do? How can I get across the river?” One of the men stretched out his shovel, saying, “Here, sit down on it, and I will throw you over the river.” The Bear’s son sat on the shovel, and the man threw him over the water to the other shore. Soon after, Moustachio came up, and asked, “Has any one passed here?” The threshers replied that a man had passed. Moustachio demanded, “How did he cross the river?” They answered, “He sprang over.” Then Moustachio went back a little to take a start, and with a hop he sprang to the other side, and continued to pursue the Bear’s son. Meanwhile this last, running hastily up a hill, got very tired. At the top of the hill he found a man sowing, and the sack with seeds was hanging on his neck. After every handful of seed sown in the ground, the man put a handful in his mouth and ate them. The Bear’s son shouted to him, “Help, brother, help!—for God’s sake! Moustachio is following me, and will soon catch me! Hide me somewhere!” Then the man said, “Indeed, it is no joke to have Moustachio pursuing you. But I have nowhere to hide you, unless in this sack among the seeds.” So he put him in the sack. When Moustachio came up to the sower he asked him if he had seen the Bear’s son anywhere. The man replied, “Yes, he passed by long ago, and God knows where he has got to before this!”

Then Moustachio went back again. By-and-by the sower forgot that Bear’s son was in the sack, and he took him out with a handful of seeds, and put him in his mouth. Then Bear’s son was afraid of being swallowed, so he looked round the mouth quickly, and, seeing a hollow tooth, hid himself in it.

When the sower returned home in the evening, he called to his sisters-in-law, “Children, give me my toothpick! There is something in my broken tooth.” The sisters-in-law brought him two iron picks, and, standing one on each side, they poked about with the two picks in his tooth till the Bear’s son jumped out. Then the man remembered him, and said, “What bad luck you have! I had nearly swallowed you.”

After they had taken supper they talked about many different things, till at last the Bear’s son asked what had happened to break that one tooth, whilst the others were all strong and healthy. Then the man told him in these words: “Once upon a time ten of us started with thirty horses to the sea-shore to buy some salt. We found a girl in a field watching sheep, and she asked us where we were going. We said we were going to the sea-shore to buy salt. She said, ‘Why go so far? I have in the bag in my hand here some salt which remained over after feeding the sheep. I think it will be enough for you.’ So we settled about the price, and then she took the salt from her bag, whilst we took the sacks from the thirty horses, and we weighed the salt and filled the sacks with it till all the thirty sacks were full. We then paid the girl, and returned home. It was a very fine autumn day, but as we were crossing a high mountain, the sky became very cloudy and it began to snow, and there was a cold north wind, so that we could not see our path, and wandered about here and there. At last, by good luck, one of us shouted, ‘Here, brothers! Here is a dry place!’ So we went in one after the other till we were all, with the thirty horses, under shelter. Then we took the sacks from the horses, made a good fire, and passed the night there as if it were a house. Next morning, just think what we saw! We were all in one man’s head, which lay in the midst of some vineyards; and whilst we were yet wondering and loading our horses, the keeper of the vineyards came and picked the head up. He put it in a sling and, slinging it about several times, threw it over his head, and cast it far away over the vines to frighten the starlings away from his grapes. So we rolled down a hill, and it was then that I broke my tooth.”