Chapter 6

OCEANUS

"Try oncet more, Lucy! Just oncet more!" Grandpa was imploring the operator.

Paul and Maureen were on the floor at Grandpa's feet, listening anxiously. Grandma brought in the lantern and set it on the organ near him as if somehow it would help them all hear better.

After an unbearable wait Grandpa bellowed, "Tom! That you, Tom? How are my ponies?"

A pause.

"What's that? You're worried about your son's chickens!" Grandpa clamped his hand over the mouthpiece and snorted in disgust. He summoned all of his patience. "All right, tell me 'bout the chickens, but make it quick." He held the receiver slightly away from his ear so that everyone could listen in.

"My son," Tom Reed was shouting as loud as Grandpa, "raises chickens up to my house, you know."

"Yup, yup, I know."

"He's got four chicken houses here, and he comes up about eight o'clock tonight, and wind's a-screeching and a-blowing, and the stoves burn more coal when the wind blows hard."

"I know!" Grandpa burst forth in annoyance. "But what about...."

"He puts more coal on and he asks me to help, and tide wasn't too far in then. But when we'd done coaling, he goes on back to his house. And an hour or so later he calls me up all outa breath. 'Tide's risin' fast,' he says. 'Storm's worsening. I can't get back up there. Will you coal the stoves for me?' So I goes out...."

Grandpa stiffened. "What'd ye find, Tom? Any o' my ponies?"

"All drowned."

A cry broke from the old man: "All ninety head?"

"They was all drowned, two thousand little baby chicks. They was sitting on their stoves like they was asleep. The water just come right up under 'em. I guess two-three gasps, and they was all dead."

"Oh." Grandpa held tight to his patience. He was sorry about the chickens, but he had to know about his ponies. He cleared his throat and leaned forward. "Tom!" he shouted. "What about my ponies?"

There was a long pause. Then the voice at the other end stammered, "I don't know, Clarence, but no cause to worry—yet. Stallions got weather sense. They'll just drive their mares up on little humpy places."

Grandpa wasn't breathing. His face turned dull red.

"They must of sensed this storm," the voice went on. "Tonight after I watered 'em, they just wanted to stay close to the house. But I drove 'em out to the low pasture like always. I'll go out later with my flashbeam. You call me back, Clarence."

There was a choking sound. The children couldn't tell whether it was Grandpa or a noise on the line.

"You hear me, Clarence? I'll go out now. Call me back."

Blindly Grandpa put the receiver in place. He went to the window and stood there, his head bowed.

No one knew what to say. Their world seemed to hang like a rock teetering on a cliff.

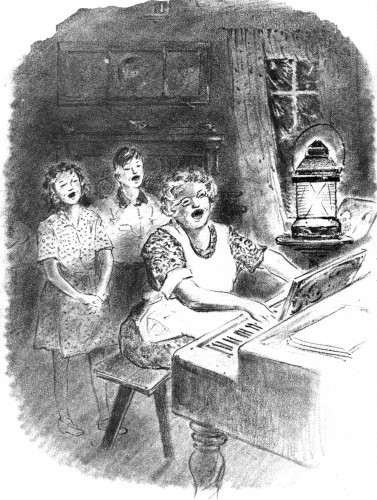

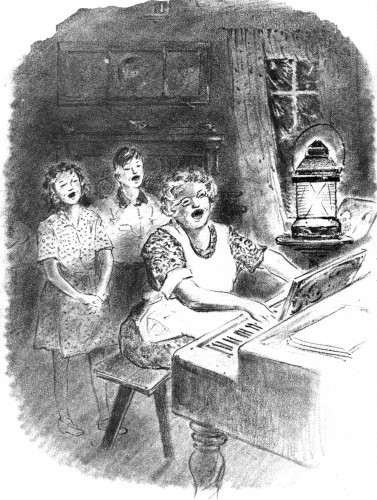

The quiet felt heavy in the room, with only the wind screaming. Suddenly Grandpa turned around. His eyes seemed to throw sparks. "Idy! Play something loud. Bust that organ-box wide open. March music, mebbe. Anything to drown out that wind. And Paul and Maureen, quit gawpin'. Get up off'n the floor and sing! Loud and strong. Worryin' won't do us a lick o' good."

Grandma was relieved to have something to do. She plumped herself on the organ bench, spreading out her skirt as if she were on the concert stage. "Now then," she turned to Grandpa, "I'll play 'Fling Out the Banner.'"

"I don't know the words," Paul said.

"Me either," Maureen chimed in.

"Ye can read, can't ye?" Grandpa barked. "Here's the song book. Go ahead now. I'll be yer audience."

The organ notes rolled out strong and vibrant, and the children sang lustily:

"Fling out the banner, let it float

Skyward and seaward, high and wide...."

When they were well into the second verse, Grandpa silently tiptoed into the hall, put on his gumboots and slicker, and let himself out into the night.

A flying piece of wood narrowly missed his head as he went down the steps, and a piece of wet pulpy paper hit him full in the face. He wiped it off and focused his light to see the path to the corral. But there was no path; it was covered by water. He drew his head into his coat and sloshed forward, bent double against the wind. "'Tain't a hurricane, it's naught but a full tide," he kept telling himself. "Still, I don't like it, with Misty so close to her time."

Inside the shed all was dry and warm. Misty was lying asleep, with Skipper back-to-back. The light brought the collie to his feet in a twinkling. He almost knocked Grandpa down with his welcome. Misty opened wide her jaws and yawned in Grandpa's face.

He couldn't help laughing. "See!" he told himself. "Nothing to worry about. Hoss-critters is far smarter'n human-critters." He fumbled in his pocket and found a few tatters of tobacco and said to himself, "Watch her come snuzzlin' up to me." And she did. And he liked the feel of her tongue on his hand and the brightness of her eye in the beam of his flashlight.

Affectionately he wiped his sticky palm on her neck and said, "I got to go in, Misty, now I know ye're all right. See you in the morning, and by then all the water'll slump back into the ocean where it b'longs."

When he came into the kitchen, Grandma was standing with a broom across the door. "Praises be, ye're safe!" she exclaimed. "I been holdin' these young'uns at bay. They wanted to follow ye."

"Grandpa! Has the colt come?" Maureen and Paul asked in one breath.

"Nope. And if I'm any judge, 'tain't soon. Now everybody to bed. Things is all right. We got to think that."

"Paul and I, we can't go to bed yet," Maureen protested.

"And why can't ye?"

"We haven't done our homework."

"Clarence," Grandma said, "you're all tuckered out, and you can't call Tom Reed 'cause our telephone's dead as a doorknob. So you go on to bed. I'll listen to the homework so's no more members of this household tippytoe out behind my back."

Grandpa patted everyone good night and went off, loosening his suspenders as he went.

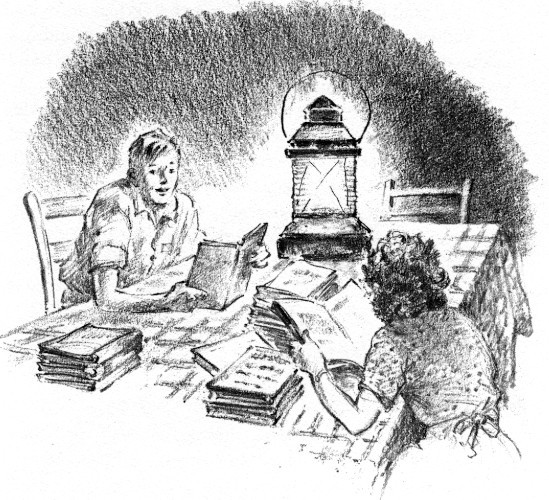

"I feel like Abraham Lincoln studying by candlelight," Maureen said, bringing her pile of books close to the lantern.

"Wish you looked more like him," Paul teased, "instead of like a wild horse with a mane that's never been brushed."

"Humph, your hair looks like a stubblefield."

"Children, stop it!" Grandma interrupted. "Ye can have yer druthers. Either ye go to bed or ye get to work."

Paul weighed the choices, then reluctantly opened his science book. But at the very first page he let out a whistle. "Listen to this! 'If the ancients had known what the earth is really like, they would have named it Oceanus, not Earth. Huge areas of water cover seventy per cent of its surface. It is indeed a watery planet.'"

"Now that's right interesting," Grandma said, putting a few sticks of wood into the stove.

"Yes," Maureen pouted, "a lot more interesting than trying to figure how many times 97 goes into 10,241."

Paul waxed to his lesson as a preacher to his sermon. "Listen! 'People used to say the tides were the breathing of the earth. Now we know they are caused by the gra-vi—gra-vi-ta—gra-vi-ta-tion-al pull of the moon and sun.'"

"I do declare!" Grandma said. "It makes my skin run prickly jes' thinkin' about it."

"Go on!" Maureen urged. "What's next?"

Paul read half to himself, half aloud. "'When the moon, sun, and earth are directly in line—as at new moon and full moon—the moon's and the sun's pulls are added together and we have unusually high tides called spring tides.'"

Grandma sat rocking and repeating, "I declare! I do declare!" until her head nodded. Suddenly she jerked up and looked at the clock. "Paul Beebe! Stop! It's way past ten and, lessons or no, we all got to get to bed. This instant!"