Chapter 5

NINETY HEAD

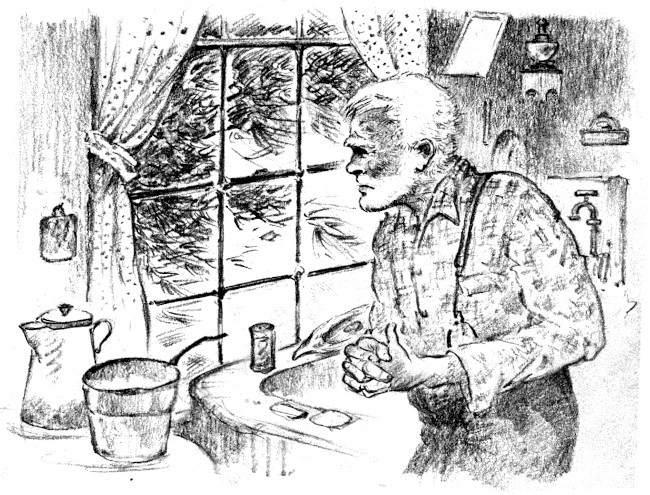

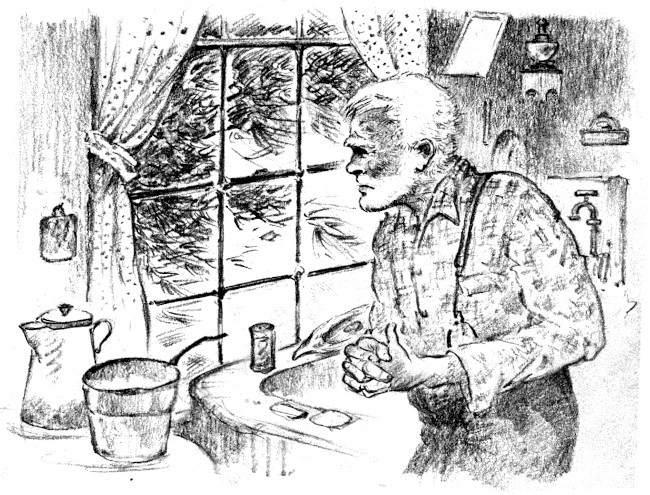

Before second helpings the storm struck in full fury. It came whipping down the open sea like some angry, flailing giant. It shook the house, rattled the shutters, clawed at the shingles.

The kitchen, so snug and secure a moment ago, suddenly seemed fragile as an eggshell.

Grandpa and the children rushed to the sitting-room window. They could not see beyond the windowpane itself. Only wind-driven rain, streams of rain, slithering down the glass, bubbling at its edges. Every few moments one ghostly beam from the lighthouse over on Assateague sliced through the downpour—then all was blackness again.

Maureen tugged at Grandpa's sleeve. "Grandpa! What if Misty's baby is being born? Right now? Will it die?"

Paul, too, felt panic. "Grandpa!" he yelled. "Let's go out there."

But Grandpa stood mesmerized. He wasn't seeing this storm. He was in another storm long ago, and he was thinking: "'Twas the wind and waves that wrecked the Spanish ship and brought the ponies here. What if the wind and waves should swaller 'em and take 'em back again!" In his darkened thoughts he could see the ponies fighting the wreckage, fighting for air, fighting to live.

And suddenly he began to pray for all the wild things out on a night like this. Then he thought to himself, "Sakes alive! I'm taking over Idy's work." He turned around and saw her at the sink washing the dishes as if storms were nothing to fret about. A flash of understanding shuttled between them. They would both hide their fears from the children.

Paul's voice was now at the breaking point. And Grandpa knew the questions without actually hearing the words. But he had no answer. He, too, was worried about Misty. He put one arm around Paul and another around Maureen, drawing them away from the window, pulling them down beside him on the lumpy couch.

"There, there, children, hold on," he soothed. "Buckle on your blinders and let's think of Fun Days. I'll think first. I'm a-thinkin'...."

In the dark room it was almost like being in a theater, waiting for the play to begin. And now Grandpa was drawing the curtain aside.

"I'm a-thinkin'," he began again, "back on Armed Forces Day, and I'm a-ridin' little Misty in the big parade 'cause you two both got the chickenpox. Recomember?"

"Yes," they agreed politely. And for Grandpa's sake, Paul added, "Tell us about it."

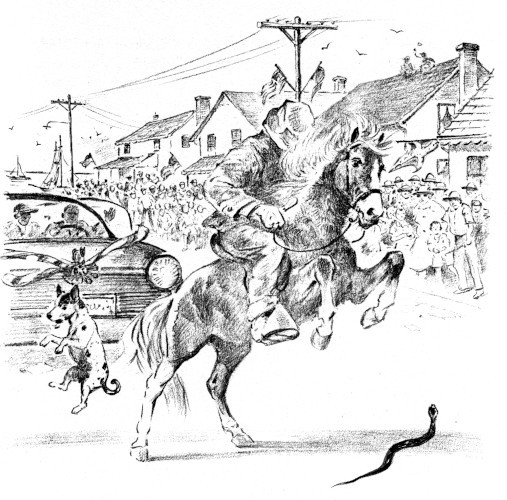

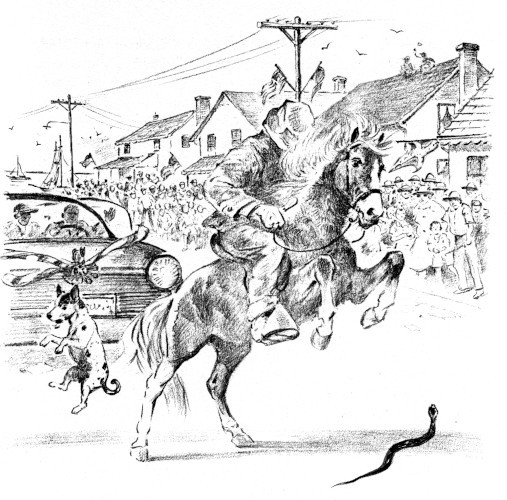

"Why, I can hear the high-school band a-tootlin' and a-blastin' as plain as if 'twas yesterday. And all of 'em in blue uniforms with Chincoteague ponies 'broidered in gold on their sleeves. And now comes the Coast Guard, carryin' flags on long poles, marchin' to the music, and right behind 'em comes me and the firemen a-ridin'."

Now the children were caught up in the drama, reliving the familiar story.

"Misty, she weren't paradin' like the big hosses the firemen rode. She come a-skylarkin' along, and ever'where a little rife of applause as she goes by. But all to once she seen a snake—'twas one of them hog-nose vipers—and 'twas right plumb in the middle of the street, and she r'ared up and come down on it and kilt it whilst all the cars in the rear was a-honkin' 'cause she's holdin' up the parade."

Grandpa stopped for breath. He gave the children a squeeze of mingled pride and joy. "Why, she was so riled up over that snake she like to o' dumped me off in the killin'. But I hung on, tight as a tick, and I give her a loose rein so's she could finish the job, and...."

Maureen interrupted. "Grandpa! You forgot all about our pup."

Grandpa winked at Grandma. His trick had worked. He had lifted the children out of their worry. "Gosh all fish-hawks," he chuckled, "I eenamost did. What was that little feller's name?"

"Why, Whiskers!" Maureen prompted.

"'Course," Grandpa said, scratching his own whiskers as he remembered. "Well, that pup was a-ridin' bareback behind me, and when Misty r'ared, he went skallyhootin' in the air. But you know what? He picked himself up and jumped right back on, after the snake-killin' was done. And Misty won a beautiful gold cup for bein' the purtiest and bravest pony in the hull parade."

"And that was even afore she became famous in the movie," Paul added.

Grandpa stopped, groping in desperation for another story. In the short moment of silence a gust of wind twanged the telephone wires and wailed eerily under the eaves.

Maureen's face went white. "Oh, Grandpa!" she whimpered. "Is Misty's baby going to die?"

"No, child. How often do I got to tell you I'm the oldest pony raiser on this-here island, and if I know anything at all about ponies, Misty'll hold off 'til the storm's over and the sun's shinin' bright as a Christmas-tree ball."

Paul leaped from the couch. "Grandma!" he challenged. "Do you believe that?"

Grandma was putting away the last of the dishes, and did not reply. The question was so simple, so probing. She wanted to tell the truth and she wanted to calm the children. "As ye know," she said at last, "I had ten head o' children, and it seemed like they did the deciding when was the time to appear. But from what yer Grandpa says, ponies is smarter'n people. They kin hold off 'til things is more auspicious."

Grandpa brushed the talk aside. "I got another worriment asides Misty," he said. "She's safe enough on high ground and in a snug shed. But what about all my ponies up to Deep Hole?" He jerked up from the couch. "I got to call Tom Reed."

"Clarence," Grandma reproached, "Tom Reed's an early-to-bedder. Time we bedded down, too. It's past nine."

"I don't keer if it's past midnight," he cried in a sudden burst. "I got to call him!" But he didn't go to the phone. He suddenly stood still, his hands clenched into fists. "Somethin' I been meanin' to tell ye," he said with a kind of urgency.

No one helped him with a question. Everyone was too bewildered.

"All I know in this world is ponies. Ponies is my life," he went on. "And ever' Pony Penning I buy me some uncommon purty ones." Now the words poured from him. "Some fellers salt their money in insurance and such, but I been saltin' mine in ponies. And right now I got ninety head. And they're up to Deep Hole in Tom Reed's woods. I got to know how they are!"

"Ninety head!" Grandma gasped. "I had no idea 'twas so many."

"Well, 'tis." Grandpa's voice was tight and strained. "If the ocean swallers 'em, we're licked and done." He looked at the children. "And there'll be no schoolin' for this second brood o' ours." He rubbed the bristles in his ears, the worry in his face deepening. "One of the ponies is Wings."

"Oh ... oh...." Maureen's lips trembled as if she had lost a friend. "Not Wings!"

"Not Wings!" Paul repeated.

"Who's Wings?" Grandma demanded.

"Why, Grandma," Paul said, "he's the red stallion who stole Misty away for two weeks last spring. Don't you remember? He's the father of Misty's unborned colt."

Maureen went over to Grandpa and took his gnarled old hand into hers and pressed it against her cheek. "Tonight I'm going to send up my best prayer for Wings. And for all ninety head," she added quickly. "But, Grandpa, we don't mind about school. Honest we don't."

"'Course not," Paul said. "We'll just raise more ponies from Misty."