Chapter 4

LET THE WIND SCREECH

The storm was sharpening as Paul moved the truck. If he hurried, he could look in on Misty once more. Skipper read his thoughts and leaped out with him, but he didn't dash ahead. He hugged close to Paul, his action saying, "Two creatures against the storm are better than one."

The wind swept down upon them and struck with an iron-cold blast. It took Paul's breath. He had to fight his way, reaching up, grasping for the clothesline. He might not be able to get out again. Suppose Misty'd already had her colt and was too frightened to take care of it? Suppose it suffocated in its birthing bag because no one was there to tear it open?

He stumbled over a tree root, and only the clothesline kept him from sprawling. But now he had to let go. He had reached the post where the line turned back to the house. He was almost to the corral. Now he was there. He squeezed through the bars. He reached the shed, crying out Misty's name.

She came to him, her breath warm on his face. He put both arms around her body. The colt was still safe inside her. A wave of love and relief washed over him as he leaned against her, enjoying the warmth of her body. He stood there, wondering what she would say to him if she could, wondering whether she was thinking at all, or just feeling content, rubbing up against a fellow-creature for comfort.

Skipper nosed in between them, nudging first one and then the other, wanting to be part of the kinship.

"You can stay in here tonight, feller," Paul said. "You'll keep each other warm." Reluctantly he left them and headed toward the house. The wind and rain were at his back now, pushing him along as if he were in the way.

The kitchen felt cozy and warm by contrast, and the acrid smell of the coal oil seemed pleasant. The light, though feeble, didn't hide the worry on Grandma's and Grandpa's faces. But Maureen was humming and happy, her head bent over small squares of paper. Wait-a-Minute was perched on her shoulder, purring noisily.

Paul picked up the cat, warming his fingers in her fur. "What you doing, Maureen?" he asked.

She folded one of the squares and held it up in triumph. "Isn't it exciting, Paul?"

"What's it supposed to be?"

"Why, a birth announcement, of course."

"Gee willikers! Horsemen don't send out announcements!"

"I know that. But Misty's different. Everybody's heard how she came from the wild ones on Assateague and chose to live with us 'stead of her own kin."

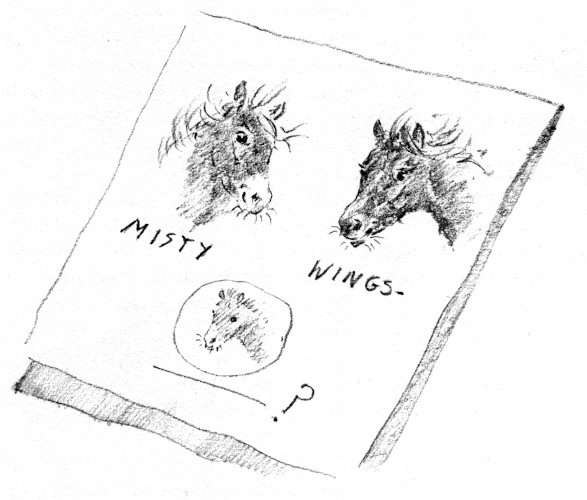

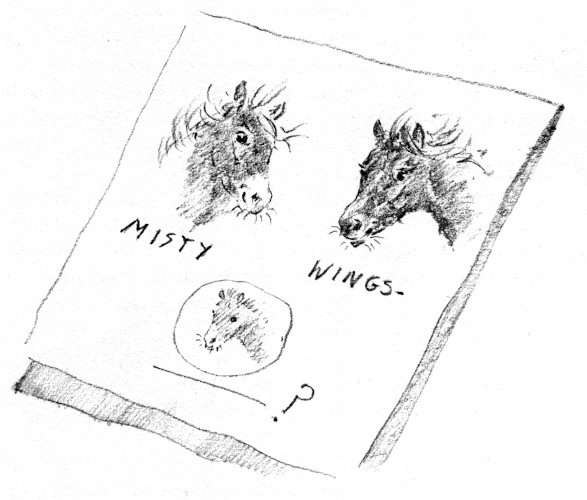

Paul held the folder close to the light. He studied it curiously and in surprise. On the top sheet were three sketches of horses' heads. The one on the left was unmistakably Misty, and the one on the right could have been any horse-creature except that it was carefully labeled "Wings." Between the two, in a small oval, there was a whiskery colt's face and underneath it a dash where the name could be printed in later.

"Right purty, eh, Paul?" Grandpa asked.

"Look at the inside," Grandma urged.

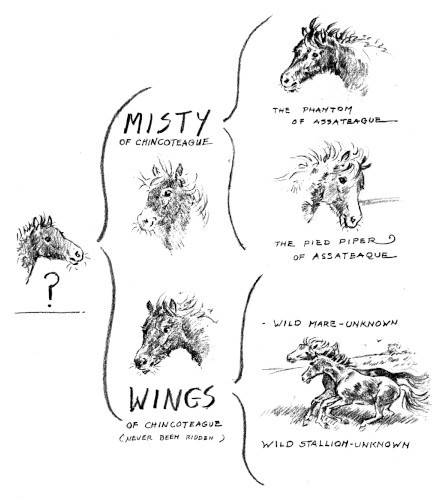

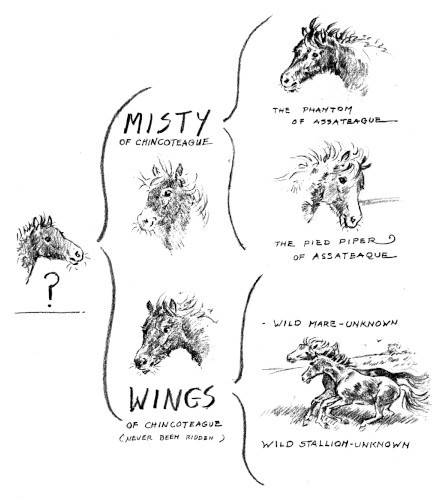

Paul opened it and read aloud: "Little No-Name out of Misty by Wings. Misty out of The Phantom by The Pied Piper. Wings out of a wild mare by a wild stallion." He pulled at his forelock, thinking and studying the pedigree.

"One thing wrong," he said with authority.

Maureen's lips quivered. "Oh, Paul, I can't help it if I can't draw good as you."

"It's not that, Maureen. The pictures are nice. Better than I could do," he admitted honestly. "But in pedigrees the stallion's name and his family always come first."

"But, Paul, remember how Misty's mother outsmarted the roundup men every Pony Penning until she birthed Misty? The Pied Piper was penned up every year, and if it hadn't been for Misty, likely The Phantom never, ever would of been captured. Remember?"

"'Course I remember! I brought her in, didn't I?" He stopped and thought a moment. "But I reckon you're right, Maureen. This pedigree is different. Misty and The Phantom should come first."

"These children got real hoss sense, Idy," Grandpa bragged. "I'm so dang proud o' them I could go around with my chest stickin' out like a penguin." He strutted across the room, trying to stamp out his worry.

Suddenly the lights flashed on and a voice blared over the radio: "... is in the grip of the worst blizzard of the winter. Twelve inches of snow have fallen in central Virginia and still more to come. At Atlantic City battering seas have undercut the famous board walk. Great sections of it have collap...." The voice was cut off between syllables as if the announcer had been strangled. Again the house went dark, except for the flame in the lantern and a rim of yellow around the stove lids.

"Supper's ready," Grandma sang out in forced cheerfulness. "Guess we can all find our mouths in the dark. These oysters," she said as she ladled the gravy over each plate, "is real plump, and the batter bread is light as a ... as a...."

"As a moth?" Paul prompted.

"Well, mebbe not that light," Grandma replied.

They all sat down in silence, listening to the sound of the wind spiralling around the house. Suddenly Grandpa pushed his chair back. "I can't eat a thing, Idy," he said. "But you all eat. I just now thought 'bout something."

"'Bout what, Clarence?"

"'Bout Mr. Terry."

Grandma put down her fork. "That's the man who moved here to Chincoteague last fall, ain't it?"

As Grandpa nodded his head, Paul broke in. "He's the man who has to live in a kind of electric cradle."

"That's the one. His bed has to rock, Idy, or he dies. And now with the electric off, he may be gaspin' for air like a fish out o' water. Me and Paul could go over and pump that bed by hand."

He hurried into the sitting room, to the telephone on the little table by the window. "Lucy," he told the operator, "please to get me Miz' Terry. She could be needin' help."

Grandma put Grandpa's plate back on the stove. Everyone stopped eating to listen.

"That you, Miz' Terry?" Grandpa's voice boomed above wind and storm.

Pause.

"You don't know me, but this here's Clarence Beebe over to Pony Ranch, and I was jes' a-wonderin' how ye'd like four mighty strong arms to pump yer husband's bed by hand."

There was a long pause.

"Ye don't say! Wal now, ain't that jes' fine. But ye'll call me if ye need hand-help, eh?"

Grandpa strode back to the table, sat down and stuffed his napkin under his chin.

"What did Miz' Terry say?" asked Grandma, setting his plate in front of him.

Grandpa ate with gusto. He slurped one oyster, then another, before he would talk. "Why, ye'd never believe it, Idy, how quick people think! First, Charlie Saunders, who's in charge of the hull Public Service—he calls Miz' Terry and warns her 'bout the wind bein' high and the electric liable to go out, so she calls Henry Leonard down to the hardware store, and almost afore she hung up there was a boy knockin' at her door with a generator and some gasoline to run it."

Grandpa sighed in satisfaction. "So let the wind screech," he said, "and let the rain slap down, and let the tide rip. We're all here together under our snug little roof."

A good feeling came into the room. The lantern flame seemed suddenly to shine brighter and the homely kitchen with its red-checkered cloth became a thing of beauty.