CHAPTER VI

HOW CONRADT PLOTTED MISCHIEF, AND HOW WULF WON A FRIEND

It was perhaps a matter of six weeks after Wulf’s coming to the Swartzburg that he sat, one day, in a wing of the stables, cleaning and shining Herr Banf’s horse-gear. He was alone at the time, for all of the younger boys and hangers-on of the place were gone about the matter of a rat-catching trial between two rival dogs whose bragging owners had matched them; and of the others, most had ridden with the baron on a freebooting errand against a body of merchants known to be traveling that way with rich loads of goods and much money. Only Herr Werner, of all the knights, was at the castle.

Save for Hansei, who stood by him stoutly, Wulf had as yet made no friends among his fellow-workers, but full well had he shown himself able to take his own part; so that his bravery and prowess, and his heartiness to help whenever a lift or a hand was needed, had already won him a place and fair treatment among them. Moreover, his quick wit and craft with Siegfried, the terror of the stables, made the master of horse his powerful friend. And, again, Wulf was already growing well used to the ways of the place, so that it was with a right cheerful and contented mind that he sat, that day, scouring away upon a rusty stirrup-iron.

Presently it seemed to him that he heard a little noise from over by the stables, and peering along under the arch of the great saddle before him, he saw a puzzling thing. Crossing the stable floor with wary tread and watchful mien, as minded to do some deed privily, and fearful to be seen, was Conradt.

“Now what may he be bent upon?” Wulf asked of his own thought. “No good, I’ll lay wager!” And he sat very still, watching every movement of the little crooked fellow.

Down the long row of stalls went the hunchback, until he reached the large loose box where stood Siegfried. The stallion saw him, and laid back his ears, but made no further sign of noting the newcomer. Indeed, since Wulf had been his tender the old horse had grown much more governable, and for a month or more had given no trouble.

Conradt’s face, however, as he drew nigh the stall, was of aspect so hateful and wicked that Wulf stilly, but with all speed, left his place and crept nearer, keeping in shelter behind the great racks of harness, to learn what might be toward. As he did so he was filled with amaze and wrath to see the hunchback, sword in hand, reach over the low wall of the stall and thrust at Siegfried. The horse shied over and avoided the blade, though, from the plunge he made, Wulf deemed that he had felt the point.

While the watcher stood dumfounded, wondering what the thing might mean, Conradt sneaked around to the other side, plainly minded to try that wickedness again, whereupon Wulf sprang forward, snatching up, on his way, a flail that lay to his hand, flung down by one of the men from the threshing-floor.

“Have done with yon!” he called as he ran; and forgetting, in his wrath, both the rank and the weakness of the misdoer, he shrieked: “What is’t wouldst do? Out with it, ere I husk thy soul from its shell with this!” and he raised the flail.

Taken unaware though he was, Conradt, who was rare skilful at fence, guarded on the instant, and by a clever twist of his blade cut clean in twain the leather hinge that held together the two halves of the flail. ’Twas a master stroke whereat, angry as he was, Wulf wondered, nor could he withhold a swordsman’s delight in the blow, albeit the sword’s wielder was plain proven a ruffian.

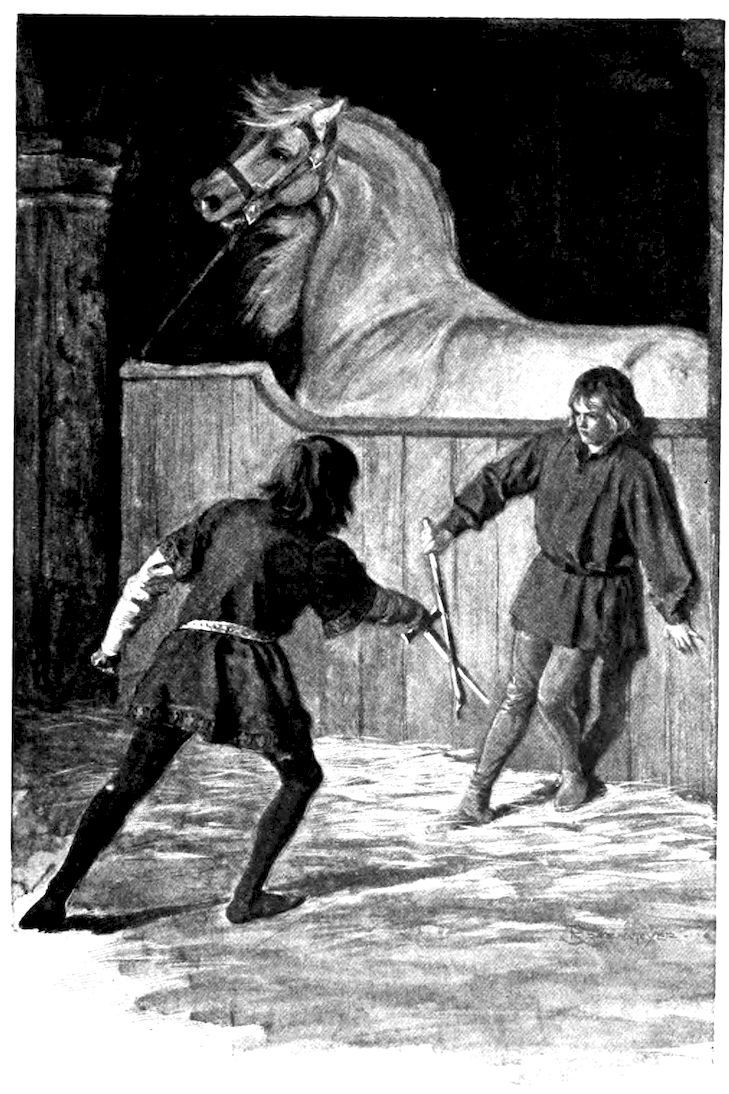

“WULF COULD NAUGHT BUT FEND AND PARRY WITH HIS STICK.”

He had small time to think, however, for by now Conradt let at him full drive, and he was sore put to it to fend himself from the onslaught, having no other weapon than the handle of the flail.

Evil was in the hunchback’s eyes as he pressed up against his foe, and evil lay at his heart as well, as Wulf was not slow to be aware. The latter could naught but fend and parry with his stick; but this he did with coolness and skill, as he stood back to wall against the stall, watching every move of that malignant wight with whom he fought.

Up, down, in, out, thrust, parry, return! The sounds filled the barn. Wulf was the taller and equally skilled, but Conradt’s weapon gave him an advantage that, but for the blindness of his hatred, had soon won his way for him. But soon he was fair weary with fury, and Wulf began to think that he would soon make end of the trouble, when he felt a sharp prick, and something warm and wet began to trickle down his right arm, filling his hand. Conradt saw the stain and gave a joyful grunt.

“One for thee, tinker,” he gasped, his breath nigh spent. “I’ll let a little more of thy mongrel blood ere I quit.”

“An thou dost,” cried Wulf, stung to a fury he seldom felt, “save a drop for thyself. A little that’s honest would not come amiss i’ the black stream in thy veins.” And he guarded again as Conradt came on.

This the latter did with a rush, at which Wulf sprang aside, and ere his foe could whirl he came at him askance, catching his sword-hand just across the back of the wrist with the tip of his stick, so that for an instant Conradt’s arm dropped, and the point of his blade touched the floor. ’Twas a trick in which Wulf felt little pride, though fair enough, and he did not follow up the advantage, knowing he had his enemy beaten for the time.

The hunchback stood glaring at Wulf, but ere he could move to attack again a voice cried: “Well done, tinker. An ye had a blade our cockerel had crowed smaller, and I had missed a rare bit of sport.”

On this both boys turned, for they knew that voice; and Herr Werner came forward, not laughing now, as mostly he was, but with a sterner look on his youthful face than even Conradt had ever seen.

“Now, then, how is this?” he demanded of Wulf. “What is this brawl about?”

The boy met Werner’s eyes frankly. “He had best tell,” he said, nodding toward Conradt.

“Suppose, then, thou dost”; and Herr Werner looked at the hunchback, who, his eyes going down before the knight’s, lied, as was his wont.

“He came at me with the flail, and,” he added, unable to withhold bragging, “I clipped it for him.”

“And what hadst done to make him come at thee?”

“I did but look at the horses, and stood to play with old Siegfried, here. ’Tis become so that my uncle the baron himself may yet look to be called to account by this tinker’s upstart.”

The stern lines about Herr Werner’s mouth grew deeper.

“Heed thou this, Conradt,” he said, with great earnestness. “Yonder was I, by the pillar, and saw this whole matter. What didst plan ill to the stallion for?”

“The truth is, not to have him hereabout,” muttered Conradt, his face dark with fear and anger. “These be my uncle’s stables, and this great beast hath had tooth or hoof toll from every one about the place.”

“True, i’ the main,” Herr Werner said scornfully. “Is this why the baron hath made thee master of the horse? Shall I tell him with what zeal thou followest thy duties?”

Conradt’s face was fair distorted now; fear of his uncle’s wrath was the one thing that kept the wickedness of his evil nature in any sort of check, and well he knew how bitter would be his taste of that wrath should this thing come to the baron’s ears. So, too, knew Herr Werner, and, in less manner, Wulf; for his keen wit had taught him much during his six weeks’ service at the castle.

“What shall I say to the baron of this?” demanded Herr Werner again, as he towered above them.

“I care not,” muttered Conradt, falsely; but Wulf said:

“Need aught be said, Herr Werner? I hold naught against him, save for Siegfried’s sake,”—with a loving glance over at the great horse,—“and ’tis not likely he’ll be at this mischief again.”

“What say, thou fine fellow?” asked the young knight of Conradt; but the latter said no word.

“Bah!” cried Herr Werner, at last. “Why, the tinker lad is a truer man than thou on every showing; get hence, that I waste on thee no more of the time should go to his wound,” he added; for Wulf, in moving his arm, had suddenly flinched and his face was pale. In another moment Herr Werner had the hurt member in hand, and as he was, like most men of that rude time, somewhat skilled in caring for wounds, he had soon bandaged this one, which was of no great extent, but more painful than serious, and was quickly eased.

Meanwhile Conradt had moved off, leaving the two alone. Though it would never be set to his credit, his malice had wrought a good work; for in that hour our Wulf got himself a strong and true friend in the young knight, who was fair won by the sterling stuff that showed in the lad.

“He hath more of knightliness in him here in the stables,” thought he, as he left Wulf, “than Conradt will ever know as lord of the castle; and, by my forefathers, he shall have what chance may be mine to give him!”

And that vow Herr Werner never forgot.